26. New Testament Archaeology--Asia Minor

Related MediaTarsus

The route from the Euphrates and Antioch converged and entered the city of Tarsus. The road then ran north to the Taurus Mountains thirty miles away. The Cilician Gates were an engineered pass through the mountains 100 yards in length. The city of Tarsus was located on a navigable river. It was important as a land and sea port. It is mentioned on the Black Obelisk (c. 841 B.C.). It became Hellenized and Pompey made Cilicia a Roman province in 64 B.C. and Tarsus the residence of the Roman governor. Tarsus was then made a free city. There was a university there.1

Cyprus (See Acts 13:4-7)

The island was captured by Thutmose III of Egypt (c. 1500 B.C.). It was colonized by Phoenicians and Greeks. Rome took it from Ptolemy Auletes c. 58 B.C. and made it a province. It was transferred to the Senate in 22 B.C. The governor had the title of Pro-consul. An inscription of the year A.D. 55 names Paulus as Pro-consul. This is an anchor date in New Testament chronology. The date of the inscription (A.D. 55) is not the same as the date of Paulus (A.D. 46-48?), but it describes an event of Paulus’ period. The tenure of a Pro-consul was one year.2

Cities of Galatia

Antioch (Acts 13:13-16)

Antioch of Pisidia was founded by Hellenists and named after Antiochus. It was a fortress against Pisidia highlanders and an island of Hellenism amidst Phrygian Asiatics. There are scant references to Jews, but there was an inscription of Debbora. She was married to a well-to-do man. There are several generations of a ruling family. These Jews were receptive and less narrow than Palestinian Jews. The Greeks were imported Magnesians (members of the Greek family), but the Phrygians were different from the people in the city. There must have been some in the city, but it was primarily Greek. Antioch was made a Roman colony in 25 B.C. The chief god was Men (not moon). There was also a female goddess exalted by the Phrygians. The religion was similar to that of the Canaanites. When Paul was at Antioch, the people who were not responsive were the aristocracy (cf. 13:50). There were important women there. The inhabitants, according to Ramsay, spoke Latin. The Coloni were against Paul.

Iconium (Acts 14:1-6)

Iconium is very similar to Damascus; it is high, has a river to its door, and mountains around it. It became famous under the Seljuks: “See all the world but see Conia.”

There was a flood tradition there. The name given after the flood was eikones (Greek: images). Ramsay gives the tradition as follows: King Nannakos lived before the flood to 300 years. He learned from an oracle that when he died, all men should perish. He called the people together for great weeping. “The weeping in the time of Nannakos” appears as a proverb in 270 B.C. and antedates Jewish influence which does not come into play until much later. (The Jews first settled in Iconium c. 280 B.C. under the Seleucids.) The gods made eikones from mud after the flood, hence, the name. Ramsay says it was an old Phrygian legend which was perhaps influenced by later Judaism but not originated by it. (The Gilgamesh Epic was known to the Hittites.)

Emperor Claudius (A.D. 41-54) paid attention to the organization of Lycaonia. Three cities were named after him: Claudiconium, Claudio-Derbe, Claudio-Laodicea. These were not colonies. Paul spent more time here. It was not ruled by an oligarchy. It became an important center for Christianity in Asia Minor. Christian cults were still in existence in the time of Ramsay.

Derbe

Derbe lies at the foot of the Taurus Mountains. A conspicuous mountain rises to 8,000 feet in the south. The various mountain names were changed to Christian ones, but pagan belief survived. Derbe was the rudest of the Pauline cities and evidenced little progress. It made no strong impression on Asia Minor Christianity. It was located on the “Imperial Road.” There was considerable western influence in this town.

Lystra

Lystra was beautiful and productive but off the main road. Berea and Lystra were more alike: rustic not cosmopolitan. Travelers may have used it as a rest place to return to Iconium. Both Lystra and Derbe were cities of Lycaonia and ranked as villages under the Anatolian system. Acts 14:6 means that they were in Roman Lycaonia (Galati Lycaonia). Lystra was a colony but a young one compared to Antioch.

Summary: Tarsus was the most oriental; Antioch was a Hellenistic city or colony. All were mixed.3

Ephesus

Paul spent three years here (Acts 19:1, 8-10; 20:31) the longest in any city. Ephesus was Asiatic and Greek, going through the usual changing of hands. According to Wright, the population was about 250,000. It was on a river three miles from the sea, and its location caused it to rank with Antioch in Syria and Alexandria in Egypt. However, the river had to be dredged.

Diana (Roman name) or Artimus (Greek name) represented the mother goddess who was Asiatic and similar to the goddesses in the Canaanite pantheon (fertility cult). Her temple was one of the seven wonders of the world. Excavations go back to the strata of the eighth century B.C. There was a greater temple in 550 B.C. which was burned in 356 B.C. The Hellenistic temple was built in 350 B.C. and paid for by Alexander the Great. The city was sacked in 262 A.D. and the temple destroyed. The platform was 239 feet by 418 and the temple itself was 160 feet by 340. There were 100 columns over 55 feet high. Some were sculptured to twenty feet. The statue may have been sculptured from a meteorite (fallen from Jupiter, Acts 19:35). The month Artimision (March-April) brought tourists and pilgrims. Perhaps this was why Paul tarried (Acts 19:26).

The theater held about 25,000 people and the finest street was called the Arkadiane. It extended 1735 feet from the theater to the harbor and was paved with marble.4

1See Ramsay, The Cities of Saint Paul, p. 228. Most of the discussion that follows is from this source.

2See Wright, BA, p. 252, Zahn, New Testament Introduction, III, 464ff.

3Outline from Ramsay, Cities of Saint Paul.

4This Ephesus summary is from Parvis, BAR #2 (1945).

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

27. New Testament Archaeology--Europe

Related MediaPhilippi

The Egnatian Way was once the main thoroughfare of Philippi. Pieces of the curb stone are still visible. A small river flows about a mile from the town and must have been the one in Acts 16 (if no synagogue was available, Jews were to meet by a flowing stream).

Excavations were carried out by the French École Francaise d’Athènes (1914-1938). The Roman forum was 300 feet by 150 feet. There were temples overlooking it on each side. There was a raised platform for orators and magistrates. It was probably to this that Paul and Silas were dragged. The current ruins date from the second century A.D.

The plain of Philippi was the site of the battle for the control of the Roman Empire after the death of Julius Caesar. In 42 B.C., Antony and Octavian there defeated Caesar’s murders, Brutus and Cassius. To celebrate the victory the conquerors made the city a Roman colony, and veterans of the battle were among the first citizens (coloni, cf. πολιτεύσθε in Phil. 1:27 and πολίτευμα in 3:20). Women seemed to be prominent in the church. There was no synagogue, yet the Judaizers came in.1

Thessalonica

This city was founded by Cassander (315 B.C.) and named after the sister of Alexander the Great. It was made a free city because of its support of Antony and Octavian. It was the most populous city of Macedonia and today is a modern, important sea port. There is an arch in Thessalonica with the inscription “In the time of the politarchs…” a word that is found only in Luke (it was on the Varder gate, now removed for modern construction).

Berea

This town was quiet and off the beaten track. There was a better class of people here, and both Jews and Gentiles were saved.

Athens

The city of Athens has been very well excavated. The acropolis is 512 feet high and comes from the golden age of Pericles. After the sacred precincts of the acropolis, ranks the agora. Areopagus (Hill of Ares, god of war, hence, Mars hill in Latin) is a bare rocky hill 377 feet high. Northwest of the acropolis was Pericles’ criminal court. Paul spoke before the city officials. Unknown gods were common. Paul viewed Athens, not in her aesthetic splendor, but as a city in raw heathenism. His sermon was appropriate and forceful, but not successful. Here were the Stoics, Epicureans, and much sophistry.

Corinth

Going to Corinth involves moving from the intellectual to the commercial center of the world. Shipping went from Corinth to Cenchreae. The Corinthian Canal, built in 1881, is four miles long and allows sailors to avoid a 200 mile trip. Corinth became famous because of its port facilities. The religion of Aphrodite was practiced here. Archaeological work has uncovered the forum and an inscription mentioning Erastus, a chamberlain who was an important person (see Rom 16:23). There is an inscription “Synagogue of the Hebrews” from c. 100 B.C. to 200 A.D. Gallio was Proconsul during Paul’s time there. His name appears on an inscription at Delphi dated c. July, 51. The Isthmian Games were held between the Olympian games.2

Italy

The town of Herculaneum, 15 miles east of Puteoli, was destroyed in 79 A.D. It has an upper room with a cross. Paul spent seven days here (Acts 28:14). Pompeii has a strange inscription which may be Aramaic in Latin characters. (Perhaps: “A strange mind has driven A., and he has pressed in among the Christians who make a man a prisoner as a laughing stock.”)

The streets of Rome were nine feet wide to allow for balconies. There were 60 miles of streets which were cluttered with refuse and people. Finegan discusses the living conditions.3 The population was about 4,100,000 (quadruple today’s population).

1The above comes from Wright, BA.

2See O. Broneer, “The Apostle Paul and the Isthmian Games,” BAR #2, pp. 393-420.

3Finnegan, Light from the Ancient Past, p. 368.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

Abbreviations

Related MediaALQ Ancient Library of Qumran (Cross)

ANE condensation of ANEP/ANET (Pritchard)

ANEP Ancient Near East in Pictures (Pritchard)

ANET Ancient Near East Texts (Pritchard)

AOTS Archaeology and Old Testament Studies

BA Biblical Archaeologist

BA Wright’s Biblical Archaeology

BANE The Bible and the Ancient Near East

BAR Biblical Archaeology Review

BASOR Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research

BHS Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia

BibSac Bibliotheca Sacra

CAH Cambridge Ancient History

CTM Concordia Theological Monthly

DTS Dallas Theological Seminary

EBC Expositors Bible Commentary

IEJ Israel Exploration Journal

ISBE International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

JAOS Journal of the American Oriental Society

JBL Journal of Biblical Literature

JETS Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society

JNES Journal of Near Eastern Studies

JRAS Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

NICOT New International Commentary on the Old Testament

NIDBA The New International Dictionary of Biblical Archaeology

NTS New Testament Studies

OROT On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Kitchen)

RB Revue Biblique

SATC From Stone Age to Christianity (Albright)

TrinJ Trinity Journal

WTJ Westminster Theological Journal

ZBD Zondervan Bible Dictionary

Related Topics: Archaeology

Selected Bibliography

Related MediaAckroyd, P. R. Israel under Babylon and Persia. Oxford: Univ. Press, 1970.

Adams, J. M. (Rev. J. A. Calloway) Biblical Backgrounds, Nashville: Broadman, 1965.

Albright, W. F. From Stone Age to Christianity. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1957.

_____. Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1967.

_____. Archaeology and the Religion of Israel. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1969.

_____. “The Role of the Canaanites in the History of Civilization” in The Bible and the Ancient Near East. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961.

Anstey, A. Chronology of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1973.

Archer, Gleason. Daniel in Expositors Bible Commentary, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1979.

Avigad, N. Discovering Jerusalem. Israel: Shikmona Pub. Co., 1980.

Avi-Yonah, M. The Holy Land: From Persia to the Arab Conquests (536 B.C. to A.D. 640); a Historical Geography, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1966.

Barthélemy, D. Les Devanciers d’Aquila. Sup. to VT. Leiden: Brill, 1963.

Beall, Todd S. Josephus’ Description of the Essenes Illustrated by the Dead Sea Scrolls, Society for New Testament Studies, Monograph Series 58, Cambridge, University Press, 1988.

Beck, John C. The Fall of Tyre According to Ezekiel’s Prophecy, Th.M. Thesis, DTS.

Beckwith, R. The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1985).

Bittel, Kurt. Hattusha, The Capital of the Hittites. NY: Oxford Univ. Press, 1970.

Blaiklock, E. M. Archaeology of the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970.

_____. and R. K. Harrison. The New International Dictionary of Biblical Archaeology. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983.

Bright, John. A History of Israel. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1959.

_____. “Has Archaeology Found Evidence for the Flood?” Biblical Archaeologist Reader I, 32-40. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1961.

Brinkman, J. A. “Merodach-Baladan II” in Studies Presented to Leo Oppenheim, Chicago: Oriental Institute of University of Chicago, 1964.

Buber, S., ed., Midrasch Tanchuma, Vilna, 1885.

Cambridge Ancient History, Vols. 1-2.

Campbell, E. F. and D. N. Freedman. The Biblical Archaeologist Reader II. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1970.

_____. The Biblical Archaeologist Reader III. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1970.

_____. The Biblical Archaeologist Reader IV. Sheffield: Almond Press, 1973.

Cassuto, U. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. 2 vols. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1978.

Charlesworth, James H. Jesus and the Dead Sea Scrolls, Doubleday, 1995.

Childe, V. G. New Light on the Most Ancient East. NY: Knopf, 1929. Fourth ed. NY: F. A. Praeger, 1953.

Contenau, Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria. NY: W. W. Norton, 1966.

Conybeare, W. J. and J. S. Howson. The Life and Epistles of St. Paul. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1976 (reprint).

Cook, J. M. The Persian Empire, NY: Schocken Books, 1983.

Cowley, A. Aramaic Papyri. Oxford: Clarendon, 1923.

Crockett, W. D. A Harmony of Samuel Kings and Chronicles. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1959.

Cross, F. M. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973.

_____. Ancient Library of Qumran. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961.

Curtis, Adrian. Ugarit, Ras Shamra. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1985.

Custance, A. The Three Sons of Noah. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1975.

Daiches, Samuel. The Jews in Babylonia in the Times of Ezra and Nehemiah according to Babylonian Inscriptions, London: Jews’ College, 1910.

Davies, P. R. In Search of “Ancient Israel,” Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1992.

Day, John. “Religion of Canaan” in Anchor Bible Dictionary 1:834

de Sélincourt, A. The World of Herodotus. Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1962.

Deuel, Leo. The Treasures of Time. NY: World, 1961.

DeVaux, R. The Bible and the Ancient Near East. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971.

_____. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

_____. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

DeVries, C. E. “The Bearing of Current Egyptian Studies on the Old Testament” in New Perspectives on Old Testament Study. Waco, TX: Word Publisher, 1970.

Donner, H. and W. Rollig. Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften. 2:6. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1968.

Driver, S.R. The Book of Genesis. London: Methuen & Co., 1905.

Dupont-Sommer, A. The Essene Writings from Qumran, G. Vermes, trans. (Glouchester, MA: Peter Smith, 1973).

Durant, W. Our Oriental Heritage. Vol. 1 of History of Civilization, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1935.

Edwards, I. E. S., Ed. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: University Press, 1970.

Eisenman, R. and Michael Wise. The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered. Rockport, MA: Element, 1992.

Eissfeldt, O. Introduction to the Old Testament. Tr. P. Ackroyd. NY: Harper & Row, 1965.

Erlandsson, Seth. Burden of Babylon. Lund, Sweden: CWK Gleerup, n.d.

Fensham, F. C. The Books of Ezra and Nehemiah in NICOT, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982.

Finegan, Jack. Light from the Ancient Past. Princeton: University Press, 1946.

_____. In the Beginning. NY: Harper & Brothers, 1962.

Finkelstein, Israel and N. A. Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, NY: Free Press, 2000.

Fitzmyer, J. A. The Dead Sea Scrolls—Major Publications and Tools for Study, Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1975,77.

_____. The Aramaic Inscriptions of Sefîre, Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1967.

Freedman, D. N. and Jonas Greenfield. New Directions in Biblical Archaeology. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co., 1969.

Gadd, C. J. “Ur” in AOTS. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

Gardiner, A. Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: University Press, 1961.

Gardiner, A. H. and Thomas Eric Peet. The Inscriptions of Sinai. London: Egypt Exploration Society, 1952-55.

Gaster, T. The Dead Sea Scriptures. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964.

Gelb, I. J. The Study of Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1952.

Glueck, Nelson. Rivers in the Desert. NY: Farrar, Strauss, Cudahy, 1959.

_____. The River Jordan. NY: McGraw-Hill, 1968.

Gordon, Cyrus. “Biblical Customs and the Nuzu Tablets.” BA3:1 (1940) 1-12.

Gurney, O. R. The Hittites. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1954.

Hall, H. R. “The Eclipse of Egypt,” in The Cambridge Ancient History 3:251-269 (1929).

Hallo, W. W. The Ancient Near East: A History, 1971, p. 145.

Harris, Zellig. A Grammar of the Phoenician Language. New Haven: American Oriental Society, 1936.

Harrison, R. K. “Edom; Edomites,” The New International Dictionary of Biblical Archaeology, eds., Blaiklock and Harrison, Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1983.

Hilprecht, H. V. and A. T. Clay, Business Documents of Murashu Sons of Nippur Dated in the Reign of Artaxerxes I (464-424 B.C.), Babylonian Expedition 9. Phila: University of PA, 1898.

Hindson, E. E. The Philistines and the Old Testament, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1971.

Hoerth, Alfred J. Archaeology and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1998.

Josephus. Against Apion. Loeb. T. E. Page, ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965.

Kelso, J. Archaeology and Our Old Testament Contemporaries. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1966.

K. Kenyon, Archaeology in the Holy Land. 1979. Rep. Nashville: Nelson, 1985.

_____. Digging Up Jericho. London: Ernest Benn, Ltd., 1957.

_____. Royal Cities of the Old Testament. London: Barris and Jenkins, 1971.

Kitchen, K. The Ancient Orient and the Old Testament. Chicago: Intervarsity Press, 1966.

_____. The Bible in its World; the Bible and Archaeology Today. Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 1977.

_____. The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 B.C.), Warminster, Eng.: Aris & Phillips, ltd., 1986.

_____. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

Kramer, History Begins at Sumer. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1959.

Lacheman, E. R. Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1981.

Laughlin, John C. Archaeology and the Bible, NY: Routledge, 2000.

Lapp, P. Biblical Archaeology and History. NY: World Publishing, 1969.

Lemche, Niels Peter. The Israelites in History and Tradition, Louisville: Westminster: John Knox, 1998.

Luckenbill, D. D. Annals of Sennacherib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1924.

Mazar, Amihai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 BCE. NY: Doubleday, 1990.

Macqueen, J. G. The Hittites and their Contemporaries in Asia Minor. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd., 1975.

Mallowan, M. E. L. “Nimrud” in AOTS. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

Matthiae, Paolo. Ebla, an Empire Rediscovered, Tr. C. Holme. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981.

Mazar, Amahai. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 BCE. Anchor Bible Reference Library, 1992.

McCullough, W. Stewart. The History and Literature of the Palestinian Jews from Cyrus to Herod (550 B.C. to 4 B.C.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1975.

Milik, J. T. ed. Discoveries in the Judean Desert. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955.

Miller, J. Maxwell and John H. Hayes. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1986.

Mitchell, T. C. “Philistia” in AOTS. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

Montet, P. Lives of the Pharaohs. Cleveland: World Publishing Co., 1968.

_____. Egypt and the Bible. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1968.

Moore, George F. Judaism in the First Century of the Christian Era. NY: Schocken Books, 1958. Vol. 1.

Moscati, S. The Face of the Ancient Orient. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1962.

Myers, J. M. Ezra and Nehemiah in the Anchor Bible. NY: Doubleday, 1965.

Newsome, J. D., Jr., A Synoptic Harmony of Samuel, Kings and Chronicles, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1986.

Noth, M. The Old Testament World, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1962.

_____. Das System der Zwolf Stamme Israels. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1930.

Oates, Joan. Babylon, London: Thames & Hudson, 1979, rev. ed., 1986.

Olmstead, A. T. History of Palestine and Syria to the Macedonian Conquest. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1965.

_____. The History of Persia, Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1948.

Oppenheim, Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia. Chicago: University Press, 1964.

Oswalt, John N. The Bible among the Myths. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009.

Payne, J. Barton, ed. New Perspectives on the Old Testament. Waco, TX: Word Books, 1970.

Perowne, S. The Life and Times of Herod the Great, NY: Abingdon Press, 1956

Pettinato, G. The Archives of Ebla, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1981.

Petrie, W. M. F. Researches in Sinai, London: J. Murray, 1906.

Pfeiffer, C. F. Old Testament History. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1973.

_____. Tell El Amarna and the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1963.

_____. Ras Shamra and the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1962.

Pinches, T. G. “Chaldea” in International Standard Bible Encyclopaedia, 1:589, 1929 edition.

Porten, B. Archives of Elephantine. Berkeley: Univ. of Calif. Press, 1968.

Pritchard, J. B. Archaeology and the Old Testament. Princeton: University Press, 1958.

_____. Ancient Near East. Vol 1. Princeton: University Press, 1958.

_____. Ancient Near East. Vol 2. Princeton: University Press, 1975.

_____. The Ancient Near East in Pictures. Princeton: University Press, 1969.

_____. The Ancient Near East in Texts. Princeton: University Press, 1969.

_____. Gibeon Where the Sun Stood Still. Princeton: University Press, 1962.

Provan, Ian, V. Philips Long, Tremper Longman III. A Biblical History of Israel. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003.

Ramsey, Wm. M. The Cities of Saint Paul. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1960 (reprint from 1907 edition by Hodder and Stoughton, London).

_____. St. Paul the Traveler and the Roman Citizen. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1960 (reprint from 1897 edition by Hodder and Stoughton, London).

Rawlinson, G. The Origin of Nations. NY: Scribners, 1881.

Redford, D. B. Akhenaten, the Heretic King. Princeton: University Press, 1984.

Riesner, R. “Jesus, the Primitive Community, and the Essene Quarter of Jerusalem,” in J. H. Charlesworth, ed., Jesus and the Dead Sea Scrolls. NY: Doubleday, 1992.

Robertson, A. T. A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1934.

Rosenthal, F. ed., An Aramaic Handbook, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1967.

Sanders, J. A. The Dead Sea Psalm Scroll. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Press, 1967.

Sanders, N. K. The Sea Peoples, Warriors of the Ancient Mediterranean, 1250-1150, London: Thames & Hudson, 1978.

Sayce, A. H. The Hittites; the Story of a Forgotten Empire. London: The Religious Tract Society, 1903.

Scheuer, J. G. “Searching for the Phoenicians in Sardinia.” BAR 16:1 (1990) 53-60.

Schmidt, W. Der Ursprung der Gottsidee. 12 vols. Münster: Aschendorffsche, 1931.

Schoville, Keith. Biblical Archaeology in Focus, Grand Rapids: Baker, 1978.

Schürer, Emil. The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. 4 vols. Rev. and Ed. By G. Vermes and F. Millar. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1973.

Segal, M. H. The Pentateuch. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1967.

Smick, Elmer B. Archaeology of the Jordan Valley. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1973.

Snaith, N. H. The Jews from Cyrus to Herod, Nashville: Abingdon, 1956.

Speiser, E. A. Genesis in The Anchor Bible. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964.

Stern, Ephraim (ed.), The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, p. 75-87. Simon & Schuster, 1993.

Stolper, Matthew. Entrepreneurs and Empire. Leiden [Netherlands]: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, 1985.

Strack, Hermann and Paul Billerbeck, Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud und Midrasch. Munich: Beck, 1922-61.

E. Thiele. The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. Chicago: University press, 1951.

Tov, Emmanuel. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible. Augsburg: Fortress. 1992, 2001.

Thompson, Thomas L. The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel, NY: Basic, 1999.

Trevor, J. C. The Untold Story of Qumran, Westwood, NJ: Revell, 1965.

Tubb, Jonathan. Canaanites. Norman: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1998.

Unger, Merrill. Israel and the Arameans of Damascus. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1957.

Van Der Woude, A. S. “Melchisedek als himmlische Erlösergestalt in den neugefundenen eschatologischen Midraschim aus Qumran Höhle XI,” Oud Testamentische Studien, 14 (Leiden, 1965).

van Seters, John. In Search of History, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

_____. Abraham in History and Tradition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975.

Walton, John H. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2006.

Weir, C. J. M. “Nuzi” in Archaeology and Old Testament Study, ed. D. Winton Thomas, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967.

Webb, Barry G. The Book of Judges, NICOT. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012.

Whitcomb, John C., Jr. Darius the Mede, Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1975.

Whitelam, Keith W. The invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History. NY: Routledge, 1996.

Williamson, H.G.M. Ezra/Nehemiah in the Word Commentary, Waco: Word, 1985.

Wilson, John A. The Burden of Egypt. Chicago: University Press, 1951.

Wilson, Robert D. Studies in the Book of Daniel. Reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker, 2 vols., 1972.

Wiseman, D. J. Chronicles of Chaldaean Kings (626-556 B.C.) in the British Museum. London: British Museum, 1956.

_____. Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon. London: Oxford University Press, 1985.

_____. Illustrations from Biblical Archaeology. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1958.

_____ et al. Notes on Some Problems in the Book of Daniel. London: The Tyndale Press, 1965.

_____. Ed. Peoples of Old Testament Times. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973.

Wood, Leon. A Survey of Israel’s History. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970.

_____. “The Date of the Exodus.” In New Perspectives on Old Testament Study. Waco, TX: Word Publisher, 1970.

_____ and D. N. Freedman. BAR #1. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1961.

_____. Ed. The Bible and the Ancient Near East. NY: Doubleday, 1961.

Young, E. J. Isaiah in NICOT. 3 vols. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965.

Zahn, T. Introduction to the New Testament. Tr. J. LM. Trout, et alia. 3 vols. Reprint, Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1953.

Related Topics: Archaeology

Bible History And Archaeology: An Outline

Related Topics: Archaeology, Cultural Issues, History

4. The Settlement Of The World, (The Table Of Nations)

Related MediaGeneral

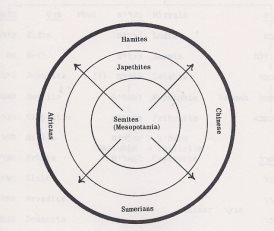

Space does not permit an extensive discussion of the table of nations presented in Genesis 10 beyond a general identification of the peoples. Custance (The Three Sons of Noah), an anthropologist, posits an interesting theory on the dispersal of man. The eight point summary of his thesis is as follows:

The geographical distribution of fossil remains is such that they are most logically explained by treating them as marginal representatives of a widespread and in part forced dispersion of people from a single multiplying population established at a point more or less central to them all, and sending forth successive waves of migrants, each wave driving the previous one further toward the periphery.

The most degraded specimens are those representatives of this general movement who were driven into the least hospital areas, where they suffered physical degeneration as a consequence of the circumstances in which they were forced to live [such as the Neanderthal man in Europe].

The extraordinary physical variability of fossil remains results from the fact that the movements took place in small, isolated, strongly inbred bands; but the cultural similarities which link together even the most widely dispersed of them indicate a common origin for them all.

What I have said to be true of fossil man is equally true of living primitive societies as well as those which are now extinct.

All the initially dispersed populations are of one basic stock: Hamitic, the family of Genesis 10.

The initial Hamitic settlers were subsequently displaced or overwhelmed by Indo-Europeans (i.e., Japethites), who nevertheless inherited, or adopted, and extensively built upon Hamitic technology and so gained an advantage in each geographical area where they spread.

Throughout the great movements of people, both in prehistoric and historic times, there were never any human beings who did not belong within the family of Noah and his descendants.

Finally, this thesis is strengthened by the evidence of history which shows that migration has always tended to follow this pattern, has frequently been accompanied by instances of degeneration both of individuals or whole tribes, usually resulting in the establishment of a general pattern of cultural relationships which parallel those archaeology has revealed.1

In Graph form, Custance’s theory looks this way:

The Genealogical List

Generally speaking, the Hamites are the most dispersed and diverse people, both ethnically and linguistically. They will be found, according to Genesis, in Asia Minor, Canaan, Egypt (North Africa), South Africa, and Mesopotamia.

Likewise, the Japethites represent the Indo-European peoples, that is, from Europe to India. This classification is usually referring to linguistic similarities rather than ethnic, although the latter is also a consideration. Looking at a relief map of the world, one can see that these people are often mountain people.

Finally, from a biblical point of view, the Semites are the center of God’s work. Semitic people come out of the desert. They are Assyrian, Babylonian, old South Arabians, and, of course, the descendants of Abraham. It is no coincidence that the three great monotheistic religions had their origin among Semitic people.

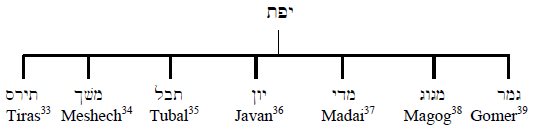

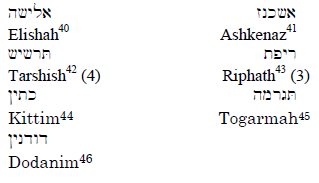

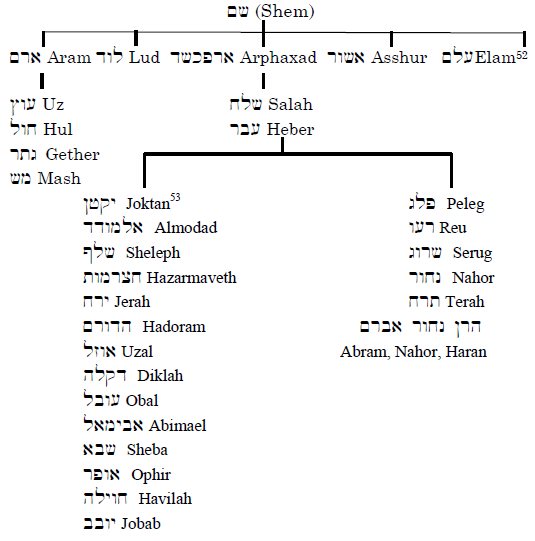

There is ongoing debate about the identification of all the names listed in the genealogies. Some are quite clear, others are not. Below is a list of all the biblical names in Hebrew and English with notes as to the assumptions about their identity.

(Tiras332, Meshech343, Tubal354, Javan365, Madai376, Magog387, Gomer398)

(Elishah409, Ashkenaz4110, Tarshish4211 (4), Riphath4312 (3), Kittim4413, Togarmah4514, Dodanim4615)

(Canaan4716, Cush4817, Seba4918, Babel5019, Erech5120)

Some General Observations

As with many genealogical lists, this one is selective and oriented toward a certain position--namely, the history of Abraham.23 Also in characteristic fashion, the most remote person (Japheth) is dispensed with and the family in the center of interest is taken up last and amplified (Shem and in ch. 11 Terah).

There are numerical considerations. Japheth has seven sons but descendants are listed for only Javan (four descendants) and Gomer (three descendants). The sons and grandsons of Cush total seven (Nimrod is dealt with as a separate entity). Mizraim has seven descendants. There are fourteen members of Yaktan’s family and ten of Shem’s consummating in Abraham (both numbers are favorites in genealogies). There are seven from Heber to Abraham. Canaan and his descendants total twelve which might be used to counterbalance the twelve tribes of Israel.

The descendants of Canaan and Mizraim are treated as peoples rather than individuals, but this is not to deny that an individual headed up the group originally.

The Israelites are linked with Heber (Gen. 10:21) apparently associating the names Heber and Hebrew.

The fact that Cushites (Hamites) are mentioned as the founders of the Mesopotamian cities shows that they must have been pushed out later by Semites (Custance argues that the Sumerians were Hamitic).

The division of the earth into languages probably took place during the time of Peleg (in his days the earth was divided) or four generations after the flood.

Excursus on Nimrod: This text presents a very tantalizing situation. A descendant of Cush became so famous his name was a household word. His very name means “rebellion” and the LXX is an early witness to an interpretation of “before the Lord” (לִפְנֵי יהוה) as “against the Lord” (ἐναντίον). All the cities mentioned are of great antiquity and are referenced in the earliest writing (cf. the Gilgamesh Epic). There is a problem of whether Asshur went out and built cities or Nimrod (or his descendants) went to Asshur and built. The latter is grammatically feasible (although a little unusual) and since Shinar has four cities, then Asshur would be given four to balance it. This would mean Semitic people in Asshur who were influenced by Nimrod.

1For a review critical of Custance’s thesis, see E. Yamauchi, “Meshech, Tubal and Company: A Review Article,” JETS 19 (1976) 239-47.

2U. Cassuto, Commentary on the Book of Genesis: Some link to Turshnoi = Etruscans, but uncertain. Note seven names.

3Ibid., Assyrian inscriptions mention Tiras and Meshech in Cilicia.

4Ezek. 27:13; 32:26; 38:2; 39:1. Southeast of the Black Sea.

5Ionians. Cassuto says they founded 12 settlements in Western Asia Minor.

6Medes near the Caspian Sea.

7Ezek. 38:2. Cassuto thinks they might be Scythians.

8Ezek. 38:6 (uttermost part of the North). CAH 3:53 says they are barbarians from the north beginning to attack Urartu and Assyria. The Assyrians called them Gimmirrai, the Greeks Kimmeroi. They were located north of the Black Sea.

9Concerned with Cyprus?

10Jer. 51:27; Scythians.

11Spain? Ezek. 27:12.

12Unknown.

13Cyprus.

14Armenia? CAH 3:55: Tilgarimu.

15Rhodes?

16Could it be that the story in Genesis 9 about Ham/Canaan was included in the Pentateuch to show the depravity of the Canaanites?

17Cassuto links him to an Arabian tribe south of Israel or Transjordan. Cf. the Cushite woman whom Moses married.

18Cassuto says they migrated south in the 8th century.

19Capital under Hammurabi.

20Uruk, Warka.

21Driver admits that inscriptions point to an early Semitic people in Elam but that the writer of Genesis would not have known that! Book of Genesis, p. 128. Childe, New Light on the Most Ancient East, argues that the very earliest settlers were Semitic Elamites (Al-Ubaid, Jemdet Nasr) who were pushed out by Indo-European Sumerians. Pp. 133-136, 145, 146.

22G. Rawlinson (The Origin of Nations, p. 209) says linguistic evidence points to a north-central population of Arabian speaking Semitic and southern population speaking non-Semitic, more related to aboriginal dialects of Abyssinia.

23Cf. Ruth 4 where only five generations are listed for 431 years and Matthew 1 where four kings are omitted. See Kitchen, Ancient Orient and the Old Testament, pp. 35-40.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

3. Writing: A Permanent System Of Communication

Related MediaGeneral

The ability to communicate in a permanent manner caused radical changes in the culture of the Middle East. People were now able to transmit information to succeeding generations in written as well as oral form. This included divine revelation as well as other more mundane matters.

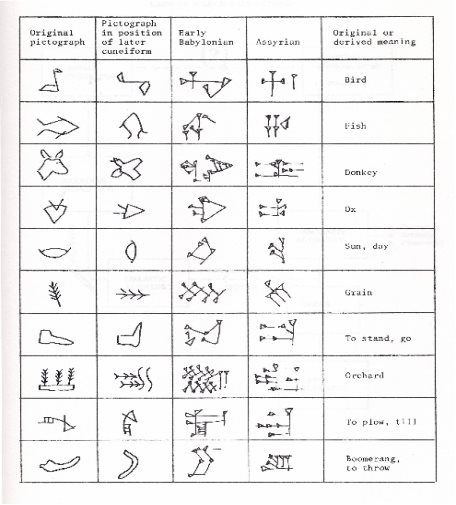

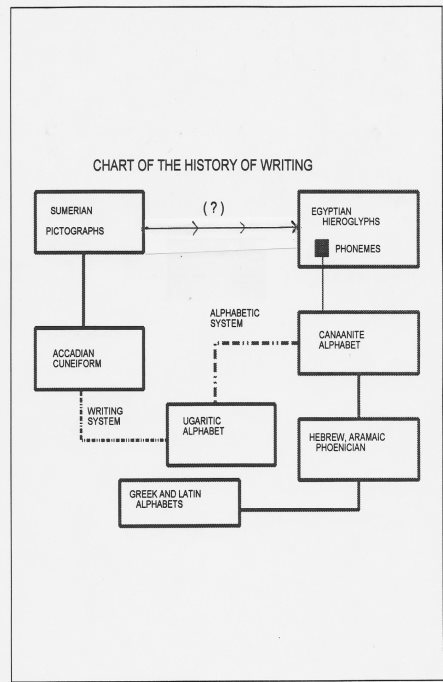

Cuneiform

Clay tablets have been found in the Mesopotamian valley with writing dated before the beginning of the third millennium B.C. Writing began with pictographic representations first on cylinder seals, then perhaps on wood, and, finally, clay. Gelb suggests a possible link between Chinese and proto-Sumerian pictographs. He gives seven ancient pictographic systems: Sumerian (3000 B.C. to A.D. 75), Elamite (3000-2000), Chinese (1300 to present), Indo (2300), Egypt (3000 to A.D. 400), Cretan (2000 to 1200), Hittite (1500-700).1

It was the medium of clay which determined the nature of writing in Mesopotamia. Figures at first were drawn, but it was discovered that the end of the stylus pressed in the clay made easier and clearer impressions. This wedged shaped writing is thus called cuneiform (Latin: wedge-shaped), or in German, Keilschrift.

Cuneiform was apparently developed by the Sumerians, an unknown people in the southern part of the Mesopotamian valley. They and their language were probably Asian in origin.2

Around the third millennium B.C., a Semitic people began to intrude into the valley, finally dominating the Sumerians completely. They adapted the cuneiform writing system to their own language which is referred to as Akkadian. The later dialectical developments of this language are referred to as Assyrian and Babylonian.

Cuneiform Akkadian is syllabic in character. That is, vowels and consonants are always written together, e.g., ab, ib, ub, aba, bab, ba, bi, etc.

Because of commercial exchanges with the west, cuneiform Akkadian has been found in Egypt, Anatolia and Syria.

Hieroglyphs

The Egyptians have writing on their monuments by 3200 B.C. These are called “holy incisions” or hieroglyphs. Gelb argues that Mesopotamian influence in Egypt c. 3000 B.C. suggests that the Egyptians learned from the Sumerians.3

Like Sumerian, this was pictograph writing, but unlike Sumerian, it was not reduced to a syllabary. The hieroglyphs are divided into sound signs or phonograms used purely for spelling (some of which stand for a single consonant) and sense signs or ideograms which depict an object or ideas connected with an object.

Cartouche of Khufu (Cheops), the great pyramid builder. The symbols outside the cartouche are translated “King of Upper and Lower Egypt.” This symbol was used by all the Pharaohs even during Greek and Persian times.

There were over 600 hieroglyphs. They contained 24 phonetic one-letter signs which do not differ greatly from the alphabet of the Semitic languages.

The hieroglyphs never evolved into an alphabet, but a cursive, simplified form was developed called hieratic which was further simplified after the 7th century B.C. into demotic.

An alphabetic system of writing Egyptian came with the adaptation of the Egyptian language to the Greek alphabet to which were added needed symbols. This is called Coptic.

The Rosetta Stone, discovered by one of Napoleon’s soldiers in 1799, contained an edict from the third century B.C., written in hieroglyphic, demotic, and Greek.

The Alphabet

The alphabet itself was left to be developed by people in Palestine. In the Sinai peninsula, the Egyptians mined turquoise. They utilized Semitic slaves for this task. In 1904-5 Flinders Petrie discovered certain inscriptions on the walls of the caves and pits in which the slaves worked. The writing was obviously an ancestor of the Phoenician and Hebrew alphabet. These letters are easily discernible in the picture in ANEP, #270. lb[lt means “to Baalat,” a goddess of the Canaanites. Albright originally dated this around 1800 B.C. but has since reduced it to about 1500 B.C. at the latest, but its development must antedate that considerably.

Precisely who developed this alphabet and when remains shrouded in mystery, but its possible connection with the Egyptian hieroglyphs has been shown. It also is a form of pictograph writing with this exception: the object represented in the symbol gives its initial sound to that symbol so that it can be used over and over again as a sound rather than a representative of one object.4 For instance, a represents an ox. The Semitic word for ox is aleph. However, a no longer means “ox,” but “a.” Likewise, [ is “eye,” (Semitic aayn), but it comes to represent “aa” as in Baalat above.5

This alphabet became refined in its shapes to the point that some of the original objects are no longer discernible. The old Phoenician, Aramaic and Hebrew inscriptions used the following alphabet:

![]()

Some of this writing appears at Qumran for the purpose of archaizing. For instance, the divine name is written ![]() in some documents.

in some documents.

Somewhere around the eighth century, through their commercial contact with the Phoenicians, The Greeks adopted and adapted this alphabet. For example, a is turned clockwise one half turn and written “A.” The Greeks wrote originally from right to left as did the Semites.6 Sometimes they wrote boustrophedon (as an ox plows) right to left and left to right. Eventually they wrote only left to right.

In view of the fact that not all letters corresponded, certain improvisations had to be made. Note the following comparison:

![]()

From Greek, of course, the alphabet spread to Latin, and its descendants. Hence, every alphabet in the world with the exception of Korean (c. A.D. 1500) owes its origin to the Semitic alphabet developed in Palestine.7

Since there were no vowels in the alphabet, each ethnic group using this alphabet had to come up with vowels. Syriac, e.g., uses Greek vowels over and under the letters. Arabic uses small slash marks and Ethiopic builds tiny vowels into the letters. Greek, itself, used existing Semitic letters for vowels (see above).

The alphabet used in the Hebrew Old Testament is not the old Hebrew but a development of that same alphabetic script by the Aramaic speaking people. The Jews adopted this alphabet during the Babylonian captivity and are using it to this day. It is referred to as the “square script.”

![]() In Syria a place called Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit) has yielded a treasure trove of tablets coming from c. 1400 B.C. These tablets are inscribed on clay with a stylus attesting their indebtedness to cuneiform, but they are alphabetic not syllabic. We assume the alphabet was borrowed from the Canaanites because of the shape of some of the letters, e.g.,

In Syria a place called Ras Shamra (ancient Ugarit) has yielded a treasure trove of tablets coming from c. 1400 B.C. These tablets are inscribed on clay with a stylus attesting their indebtedness to cuneiform, but they are alphabetic not syllabic. We assume the alphabet was borrowed from the Canaanites because of the shape of some of the letters, e.g., ![]() Canaanite samek, Ugaritic

Canaanite samek, Ugaritic ![]() . See ANEP, #263.

. See ANEP, #263.

Miscellaneous Notes

“We must again emphasize the fact that alphabetic Hebrew writing was employed in Canaan and neighboring districts from the Patriarchal Age on, and that the rapidity with which forms of letters changed is clear evidence of common use. It is certain that the Hebrew alphabet was written with ink and used for everyday purposes in the 14th and 13th centuries B.C. (Lachish, Beth-Shemesh, Megiddo), that quantities of papyrus were exported from Egypt to Phoenicia after 1100 B.C. (Wen-amun), that writing was practiced by a youth of Gideon’s time (early eleventh century), that it was known in Shiloh before 1050 B.C., that several examples of writing from Iron I (cir. 1200-900 B .C.) have been found in Israelite Palestine, and that David had a staff of secretaries. In the light of these facts, hypercriticism with regard to the authenticity of much of the material preserved by P is distinctly unscholarly, and its independent attestation of facts given by J and E is a valuable guarantee of their historicity. It is even less likely that there is deliberate invention of ‘pious’ forgery in P than in JE, in view of the well attested reverence which ancient Near-Eastern scribes had for the written tradition (see above, p. 77).”8

Sumerian is the oldest pictographs. All others seem full-blown from the beginning (indication of adoption).9 Their initial use was during foreign influence.10 There is a good possibility of monogenesis of writing.

Is there a monogenesis of language? Colliers Enc. XII, p. 141. Italian scholar Trombetti--yes, but it cannot be proved or disproved. Complete differences do not disprove it. (Once Indo-European relationship was not understood.)

From Pictography to Syllabic Writing

After Contenau, Everyday Life in Babylon an Assyria

1I. J. Gelb, A Study of Writing, p. 60.

2See Contenau, Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria, p. 186.

3Amahai Mazar (Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 BCE., p. 105) says, “Sumerian influence on Egyptian culture was considerable during the Late Gerzean and Archaic periods in Egypt. These international relations during one of the most creative periods in the history of the ancient Near East may indicate movements of people over long distances—both by land, from Mesopotamia westward through Syria to Palestine and Egypt, and by sea, connecting Elam and southern Mesopotamia with Egypt around Arabia. Within this general framework, close though short-term connections between Egypt and southern Palestine in EB I [3300-3050] are of particular significance.”

4See D. J. Wiseman, Illustrations from Biblical Archaeology.

5See Orly Goldwasser “How the Alphabet Was Born from Hieroglyphs,” BAR, March/April 2010 and Rainey’s response to her.

6Harris thinks it might be because of inscriptional use (Z. Harris. A Grammar of the Phoenician Language, p. 11).

7Jonathan Tubb, Canaanites, p. 146, “If an enduring tribute to the Canaanites is needed then it is surely the printed text of this book …The letters used may look very different from those devised in the second millennium BC, but the process of their usage, the alphabetic system, remains as the towering achievement of the Canaanites.”

8Albright, From Stone Age to Christianity, (SATC), p. 253ff.

9I. J. Gelb. The Study of Writing, pp. 212ff.

10Amihai Mazar. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 BCE, pp. 104-105.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

2. Historical Development In Archaeology, Based On Wright, Biblical Archaeology

Related MediaWhat Is Archaeology?

Biblical Archaeology is a special arm chair variety of general archaeology. Someone has quipped that it is the study of durable rubbish. The archaeologist’s chief concern is not with methods or pots or weapons alone. His central and absorbing interest is the understanding and exposition of Scripture. The biblical student must be a student of ancient life, and archeology is his aid in recovering the nature of a period long past. We cannot, therefore, assume the knowledge of biblical history is unessential to faith. Biblical theology and biblical archeology must go hand in hand if we are to comprehend the Bible’s meaning. Many facets of biblical teaching cannot be buttressed or enlightened by archaeology, e.g., the resurrection of Christ. So for this reason many will part ways in interpreting the data because of their frame of reference.

Developing Sciences.

William Smith, “Father of English Geology”--1799 stratification of rock.

Principles of Geology (1830) Sir Charles Lyell--uniformitarianism.

Huxley’s Man’s Place in Nature (1863); Darwin’s Descent of Man. Criticism of the Bible began here and peaked in the early 1900’s.

Albright moved away from his very liberal mentors and was the pillar in the “biblical archaeology” movement from the 1920’s on.

The idea that no history of Israel can be written and a minimalistic approach to the biblical text comes into play in the last part of the 20th century.

Recovery of Lost Civilizations.

Ideas of the east were poorly preserved by Greek and Latin authors. There was a dim understanding of the east. In the 17th-18th centuries, travelers began to return with reports of ancient cities. The first cuneiform writing was brought to Europe just after 1600.

Egypt.

Napoleon set off for Egypt in 1798 with an army of soldiers and scholars. Description de l’Egypt (1809-13) caused Europe to become acquainted with the dazzling empire of Egypt. The Rosetta Stone was discovered by a soldier. It contains hieroglyphics, demotic and Greek and dates from about 195 B.C. The triple text was a decree issued by a king giving exemption to priests from taxes. The Rosetta Stone provided the key to hieroglyphics.ANE#72.

Mesopotamia.

Old Persian had been deciphered but Akkadian was a puzzle. The Behistun Inscription: a steep rock face in Iran bearing a triple text inscription of Darius the Great (522-486 B.C.) in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian, (see Kramer, The Sumerians, pp. 12ff). Work had been done on trilingual inscription before the Behistun inscription, but through Rawlinson, definitive results came about. Old Persian had been learned from India. Rawlinson copied the first and third texts in 1843-47 (see National Geographic, December, 1950). The inscription was 345 feet above a spring and 100 feet above where man can climb. There was much early skepticism of the decipherment, but proof was given when a recently excavated tablet was copied and sent to four different Assyrian scholars. The translations were substantially the same, and by 1880 all were convinced.

French and British excavators were at work in the Assyrian ruins of Khorsabad and Calah where there were great palaces of Assyrian kings (see atlas). The most important single discovery was the library of Ashurbanipal (669-633 B.C.). Thousands of documents of all sorts had been copied. History, chronological lists, astronomy, math, religion, prayers, cuneiform sign lists, texts in two languages, were among the works. G. Smith discovered an account of the flood epic while working on these.1

Palestine.2

Moabite stone--1868--ANE 1 #74.

Work at Byblos--Phoenicians. 1860’s.

Ugarit--alphabet--1930’s--ANE 1 #63.

Lachish letters--1930’s--ANE 1 #80.

Gezer Calendar--ANE 1 #65.

Siloam Inscription--ANE 1 #73.

Megiddo--recent--ANE 1 #181.

Dead Sea Scrolls.

Proto-Sinai alphabet.

Arad Ostraca--BASOR, 197, February, 1970, p. 16ff.

An important publication on the materials found in Palestine is H. Donner and W. Rollig, Kanaanaische und Aramaische Inschriften, Vol. I = Text; Vol. II = Commentary; Vol. III = Glossary.

Ebla--1975-

The New ‘Ain Dara Temple: Closest Solomonic Parallel (1300-740 BC)3

The Tell Dan Stela (Beyt David)

The Pool of Siloam in Jesus’ Time

Jerusalem’s Stepped-Stone Structure (Millo)

Tell Qeyafa with the ancient ostracon

Archaeological Method.

Heinrich Schliemann was an amateur archaeologist who excavated Troy in the 1870’s. He discovered the importance of mounds (see Joshua 11:13; 8:28). It was easy to date monuments, but there are few in Palestine. Flinders Petrie found the clue in pottery in 1890 in the dig at Tell el-Hesi which is perhaps Eglon (ANE 1 #27). In the earlier days excavation was merely a treasure hunt. Now it is highly scientific. See picture of a Tell in Wright, Biblical Archaeology, p. 23, 26. Note the stratigraphic typology. See step trench in Ed Chiera, They Wrote on Clay, p. 34.

Archaeological methods have progressed dramatically, primarily through technology. Pottery sequence continues to be a major dating instrument and stratigraphy is still basic. Laughlin gives a popular and thorough presentation of the modern approach to digging. 4

1Read Pritchard’s account of the Black Obelisk, Archaeology and the Old Testament, p. 139 and his postscript, p. 246.

2The use of Palestine here is not intended to enter the debate of the modern name Israel vis à vis Palestine. This designation was used by the British Mandate after WW I.

3See “Issue 200: Ten Top Discoveries,” BAR 35:4/5 (2009) pp. 74-96.

4John C. H. Laughlin, Archaeology and the Bible.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

1. Current Attitudes On Bible History And Archaeology

Related MediaAttitudes between the 20’s and the 30’s and currently toward the Bible in the Ancient Near East, the role of archaeology and its impact on the Bible, as well as questions about whether there is such a thing as biblical archaeology have shifted dramatically. The following citations from Glueck and Wright in particular come from the fifties and sixties, when there was somewhat of an “Albrightian consensus” that was particularly salutary. Later we will discuss contemporary (1990’s) views, but for now let the men working with the Bible and archaeology in that era speak for themselves.

Nelson Glueck (Rivers in the Desert. p. 30ff) addresses the issue of the place of the Bible in the discussion of archaeology:

“The purpose of the biblical historian and archaeologist is, however, not to ‘prove’ the correctness of the Bible. It is primarily a theological document, which can never be ‘proved,’ because it is based on belief in God, whose Being can be scientifically suggested but never scientifically demonstrated.”1

“Those people are essentially of little faith who seek through archaeological corroboration of historical source materials in the Bible to validate its religious teachings and spiritual insights.”

“As a matter of fact, however, it may be stated categorically that no archaeological findings have been made which confirm in clear outline or in exact detail historical statements in the Bible. And, by the same token, proper evaluation of biblical descriptions has often led to amazing discoveries. They form tesserae in the vast mosaic of the Bible’s almost incredibly correct historical memory.”

G. Ernest Wright (“Is Glueck’s Aim to Prove that the Bible is True?” Biblical Archaeologist, XXII, December, 1959) defends the “Albrightian consensus” against the charge of holding to a biblical agenda:

“J. J. Finkelstein of the University of California presents a review of Rivers in the Desert (Commentary, April, 1959, XXVII No. 4). In actuality the article is not so much a review of Glueck’s discoveries as a critical essay on the question as to whether archaeology proves the historicity of the Bible. He takes #3 above as Glueck’s thesis and debates it.”

Finkelstein: “Wright says in his Biblical Archaeology, ‘The most surprising and discouraging result of the work so far has been the discovery that virtually nothing remains at the site between 1500 and 1200 B.C.’” (Jericho). Wright: “Finkelstein asserts that the word ‘virtually’ is simply a scholarly hedge for ‘nothing,’ and that what I am actually saying is that the site was unoccupied in the Late Bronze Age. Furthermore, says Finkelstein, my word ‘discouraging’ in this connection ‘speaks volumes on the subject of scholarly detachment in the area of Biblical studies.’ He continues: ‘The dictates of the new trend, which requires that every contradiction between archaeological evidence and the Biblical text be harmonized to uphold the veracity of Scripture, has apparently driven Dr. Wright--in this case at least--beyond the reach of common sense.’”

The Role of Fundamentalism

Wright: “There are many people both here and abroad who honestly think and frequently assert that Palestinian and biblical archaeology was conceived and reared by conservative Christians who wished to find support for their faith in the accuracy of the Bible. As a matter of actual fact, however, that is not the case at all. In the great fundamentalist-modernist controversy that reached its height before the First World War, archaeology was not a real factor in the discussion. Indeed, the discoveries relating to the antiquity of man and the Babylonian creation and flood stories were usually cited against the fundamentalist position. As for the excavations in Palestine, one need only call the roll of the leading American sponsors and contributors to indicate what the true situation has been: Harvard University (Samaria), University of Pennsylvania (Beth-Shan), University of Chicago (Megiddo), Yale University (Jerash), the American Schools of Oriental Research, etc. Palestinian archaeology has been dominated by a general cultural interest, and one can say that ‘fundamentalist’ money has never been a very important factor.2 Archaeological research by and large has been backed by the humanist opinion that anything having to do with historical research, with the investigation of our past is an obvious ‘good’ which needs no justification.”

Place of Albright

“The introduction of the theme, ‘archaeology confirms biblical history,’ into the discussion of scientific archaeological matters is a comparatively recent phenomenon. And it is to be credited to the pen of William Foxwell Albright more than to any other one person. Since the 1920’s, Albright has towered over the field of biblical archaeology as the greatest giant it has produced, and more than any other single person he has influenced younger scholars, Protestant, Catholic and Jewish, to take the subject seriously as a primary tool of historical research. At the same time, he has been a most important encouragement to young conservative scholars. Through his writings, they have come to realize that if they but master the tools of research, there is indeed a positive contribution that they can make to biblical research, and that the radical views which they could not accept do not necessarily find support in recent research.”

“Yet Albright has often been misunderstood at this point. He has never been a ‘fundamentalist’ (Note, for example, the robust attack on him as an old-fashioned liberal at heart by O. T. Allis, “Albright’s Thrust for the Bible View,” CT, May 25, 1959, Vol. III. 17, pp. 7-9), and the encouragement of that movement could scarcely be farther from his center of interest… At the same time Albright’s deep interest in ancient history and his mastery of several disciplines within it brought him to the conviction that a whole new environment for biblical study was emerging of which the 19th century knew nothing.”

“Consequently, at first in his popular writings and finally in his scholarly synthesis of the evidence (From the Stone Age to Christianity), he led the attack in the English-speaking world on the unexamined presuppositions of ‘Wellhausenism’ from the standpoint of ancient history and particularly archaeology. The early historical traditions of Israel cannot be easily dismissed as data for history when such a variety of archaeological facts and hints make a different view far more reasonable, at least as a working hypothesis, namely, that the traditions derive from an orally transmitted epic which has preserved historical memories in a remarkable way, that ‘pious fraud’ was not a real factor in the production or refraction of the traditions, and that in Israel aetiology was a secondary, never a primary, factor in the creation of the epic.”3

Conservative Archaeology

“This information from Jericho was said to be ‘disappointing,’ and the reason is this: not only is it now difficult to interpret the biblical narrative of the fall of Jericho, but it is impossible to trace the history of the tradition. For my part, I do not believe that it can any longer be thought ‘scientific’ simply to consider stories such as this one either as pure fabrications or as ‘aetiologies.’ They have a long history of transmission, oral before written, and they derive from something real in history, no matter how far removed they may now be. In a number of instances, both the origin and history of a given tradition can be made out by historical, form-critical, and other methods of study. But the problem of Jericho is more of a problem than ever, precisely because the history of the tradition about it seems impossible to penetrate.”

The Differences between the Continental and American Schools

Scoggin, J. Alberto, BA, XXIII, No. 3, September, 1960. Qin’at sofrim tarbeh hokma. (The jealousy of scholars increases wisdom.) He presents the views of Albrecht Alt and his younger contemporary Martin Noth as opposed to the Albright school represented by John Bright, A History of Israel. The former argues for complete dismissal of the historicity of anything before the constitution of the Twelve-tribe League (Amphictyony) on Palestinian soil. Whereas the latter holds the essential historicity of the traditions underlying the sources. For a more detailed discussion of this cleavage and subsequent modifications, see DeVaux, The Bible and the Ancient Near East, pp. 111-122.

Attitudes in the nineties

W. F. Albright died in 1971. An issue of the Biblical Archaeologist was devoted to “celebrating and examining” his legacy. The editor says, “W. F. Albright represents, as it were, an Atlantis of biblical and Near Eastern studies, lingering in memory and story long after slipping beneath the sea.”4 Devers is particularly devastating in his evaluation of Albright’s work.5 He says, “The fact is the ‘Biblical archaeology’ of the classic Albright-Wright style is dead, either as a serious intellectual enterprise, or as an effective force in American academic or religious life.” He goes on to say, in spite of Albright’s arguments that there was a 13th century Moses who was a monotheist, “the overwhelming scholarly consensus today is that Moses is a mythical figure, that Yahwism was highly syncretistic from the very beginning; and that true monotheism developed only late in Israel’s history, probably not until the Exile and Return (see the state-of-the-art studies gathered in Miller, Hanson, and McBride 1987).”

Thus we have come full circle: Albright rejected the excessive higher critical claims for the non-historicity of the Bible, but now his position has been rejected. We must now speak of the new archaeology not Biblical archaeology.6

Kitchen argues that Albright’s views were good based on Mari (18th century) and Nuzi (15th century). There was wide travel, semi nomadism, West-Semitic personal names, and legal/social usage.7 Kitchen goes on to say that this data has been clouded by later treatments. Gordon dated Abraham in the 14th century and identified him as a merchant prince. Others identified him as a warrior hero. Albright himself identified him as a donkey caravaneer, a traveling trader rather than a pastoralist. Speiser gave a Hurrian interpretation based primarily on Nuzi. The Patriarchs began to look more like Hurrians than Hebrews! There was a reaction, he says, against Albright’s views in the 1970’s encouraged by old style “die hards” in Germany and America. It is nothing but old German rationalism. Those who are trying to “debunk” Albright include T. L. Thompson, The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives, 1974; J. van Seters, Abraham in History and Tradition, 1975; and D. B. Redford, “A Study of the Biblical Story of Joseph,” VTSup 20 (1970).8

Albright’s general views will continue to be presented in this outline for the simple reason that I believe many of his historical conclusions are correct.

During this same period (80’s-90’s), the issue of minimalism vs maximalism arose. A small number of advocates (Whitelam,9 Thompson,10 Davies,11 Lemche,12 Finkelstein,13 e.g.) exercising a disproportionate influence on the scholarly world, argue for no historicity of the Bible prior to the sixth century B.C. So, again, we have come full circle to the place where Albright began to debunk the hyper-critical views of the 19th century. See Dever (himself no conservative) debunking this.14 Kenneth Kitchen came out with his monumental work in 2003.15 In my opinion he devastates the arguments of the minimalists.

Thompson even argues against the Tel Dan inscription that specifically mentions the house of David coming from the ninth century BC. He desperately tries to find other meanings for the words.16 Kitchen makes a slashing attack on the biblical minimalists on pp. 449-500. See his discussion of Philistines and camels during the patriarchal time on p. 465. The lack of records regarding the exodus is discussed on p. 466. He interacts with Dever’s, Who were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? on pp 468ff. “There seems to be a psychological hangover here; in the 1950s to 1960s, Albright and Dever’s much-hated ‘American Biblical Archaeology’ (plus theology) movement had believed in the patriarchs and exodus—so (irrationally) nobody now (two generations later) must either be allowed to study them seriously or to produce any data (no matter how genuine or germane) that do suggest their possible reality. In the light of what is now known, there is no excuse whatsoever for dismissing either the patriarchs (with a firm date line) or the exodus; see the entirely fresh treatments in chapters 6 and 7 above. The treatments given here by me are not based on Albright, Gordon, or the vagaries of the little local (and very parochial) United States problem of the long-deceased American Biblical Archaeology/ theology school. Archaeologists that ‘have given up hope of recovering any context that would make Abraham, Isaac or Jacob credible ‘historical figures’ (98) are not thereby rendered ‘respectable’; in fact, they simply do not know the relevant source materials (which are mainly textual), are not competent to pass judgment on the issues, and would be better described as pitifully ignorant, and can now be mercifully dismissed as out of their depth.”17

1But seeking confirmation of written documents by archaeology is not improper and practical for other documents than the Bible (Kitchen, Ancient Orient and the Old Testament, 169, 70).

2Schoville (Keith Schoville, Biblical Archaeology in Focus, p. 97) cites this statement and adds, “There is currently a trend, nevertheless, for increased financial and staff support derived from conservative circles.”

3Albright said, “In the center of history stands the Bible” (cited by J. M. Sasson, “Albright as an Orientalist,” BA, 56 [1993] 6).

4David C. Hopkins, “From the Editor,” Biblical Archaeologist 56 (1993) Inside cover.

5W. G. Dever, “What Remains of the House that Albright Built?”BA56 (1993) 32-33.

6See John van Seters (In Search of History) for a classical presentation of the newer perspective.

7See Provan, et al., A Biblical History of Israel, p. 115 for a recent discussion of Nuzi and the Patriarchs.

8K. Kitchen, The Bible in Its World, pp. 57-58. For a 1987 survey, see F. R. Brandfon, “Archaeology and the Biblical Text,” BAR 14 (1987) 54-59.

9Keith W. Whitelam, The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History, NY: Routledge, 1996.

10Thomas L. Thompson, The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel, NY: Basic, 1999.

11P. R. Davies, In Search of “Ancient Israel,” Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1992.

12Niels Peter Lemche, The Israelites in History and Tradition.

13Israel Finkelstein and N. A. Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts.

14William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel.

15K. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (OROT), Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

16 Kevin D. Miller, “Did the Exodus Never Happen?” Christianity Today, September, 1998, for a good discussion of the issues.

17Kitchen, OROT, pp. 468-469. See also a response to Dever in John Oswalt, The Bible among the Myths, pp.180-81.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

6. Egypt To 1600 B.C.

Related MediaGeneral

Egypt, like Mesopotamia, is a fluvial civilization. Unlike Mesopotamia, Egyptian history is characterized by a great stability brought about by the predictability of the annual inundations of the Nile. This river is 4,000 miles long. The White Nile, originating in Kenya, joins the Blue Nile, originating in Ethiopia, at Khartoum in the Sudan. The annual melting of the highland snows produces the flooding which brings rich alluvial soil to the banks of the Nile. The Nile produces two tensionsthere is unity because of the one river, but disunity because of its great length. These tensions are historically evident in the union of upper (south) and lower (north) Egypt. The Pharaohs will be known as the kings of upper and lower Egypt.

Cartouche of Khufu (Cheops), the great pyramid builder. The symbols outside the cartouche are translated “King of Upper and Lower Egypt.” This symbol was used by all the Pharaohs even during Greek and Persian times.

Chronology

No one pretends to be satisfied with the present chronology of Egyptian history. Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs, pp. 46-48, presents an excellent discussion of the problems. The materials from which a chronology is generally derived are as follows:

Manetho

Manetho was an Egyptian priest contemporary with the first two Ptolemies (323-245 B.C.). He listed the entire history of Egypt in two parts: first the era of gods and demi-gods and then 31 dynasties for the real history. His work is only partially preserved in the works of others (notably Josephus) and has been demonstrated to be quite defective, but the dynastic presentation has become so entrenched in Egyptology that it is still used today for the outline of Egyptian history.

Turin Canon of Kings (Papyrus)

This hieratic papyrus comes from about the time of Ramases II (1290-1224 B.C.). It is very fragmentary and yields only 80 or 90 royal names.

The Table of Abydos

An inscription from the temple of Abydos shows Seti I (1303-1290) with his oldest son, Ramases II, making offerings to 76 of his ancestors. In addition to these are the Table of Sakkara and the Table of Karnak.

The Palermo Stone

This stone is now in the museum of Palermo, Italy. It is only a fragment containing some of the names in Egyptian history. Its date, significance and extent are still much debated.

These data, synchronized in so far as possible with Mesopotamian events and astronomical date, provide a framework for the erection of Egyptian history, but, it must ever be kept in mind, that the framework is only tentative.

The Early Period--to 2700 B.C.

Racial origins and language.

Multiple political divisions.

Kingdom in south under the god Seth.

Unification of lower Egypt. First union of upper and lower under falcon kings of lower Egypt. Capital was at Heliopolis. They worshipped Horus.

Break-up of the union. Development of both kingdoms.

Conquest of lower by upper about 2900 B.C.

Dynasties I, II. 2900-2700 B.C.

The Old Kingdom-Memphis-Dynasties III-VI-2700-2200 B.C. (500 years)

Innovation and adventure mark Dynasties III-IV (400 years). The achievements of this era become “canonized” and copied by all succeeding generations. Wilson argues that cylinder seals, architecture (bricks), art, the potter’s wheel, and above all writing come from Mesopotamia.1

Religious significance of Pyramids is the preservation of the Pharaohs. Old pyramids are best here. The Great pyramid (IV dynasty) contained 6.25 million tons of stone. Some of the blocks were 2.5 tons each. The joints were 1/50th of an inch. Squareness deviation: .09 N-S, .03 E-W. Plane deviation: .004%.

Relation with neighbors--expeditions against Nubia, Libya, Palestine, Syria. Close relations with Byblos--cedar wood.

There was a slowly developing crisis from the Vth dynasty onward. The priesthood begins to ascend and feudalism begins.2

The “First Sickness”--Dynasties VII-X--2200-2000 B.C. (200 years)

There was a leveling of the Pharaoh and nobility. The administration approached that of a democracy. There was a loss of the intellectual self-confidence which had characterized the earlier period.

Egypt fell into disorganized feudalism which lasted almost four centuries. The priesthood at Heliopolis and the sun god Re become dominant.

The Middle Kingdom--Dynasties XI-XII--2000-1700 B.C. (300 years)

The XIth dynasty at Thebes began to fight for supremacy against the Fayum and eventually won. Under the XIIth dynasty, Egypt was again unified and became strong. Amon emerges and becomes the dominant god. (There is some confusion as to the placement of Dynasties XIII and XIV.)

The Egyptians penetrated to the first cataract (see the story of Sinuhe--1960-1928 B.C.).

The Egyptian standard was carried to Syria (1887-1849). JOSEPH ENTERS AROUND THIS TIME (1871 for Jacob). There is evidence for Asiatic intrusion into Egypt during the “first sickness” (see ANEP, #3).3

This is the classical period of art and literature.

The Middle Kingdom ended with the invasion of the Hyksos (“second sickness”).

The Hyksos Invasion--Second Sickness”--Dynasties XV-XVII (1700-1600 B.C.)

The Hyksos are still an obscure people in part because of the effort of their successors to eradicate any memory of them from the monuments. Josephus, quoting Manetho, believes they are the Israelites.4 He calls them “shepherd kings,” but the word is now translated “rulers of foreign lands.” There were, apparently, contemporaneous dynasties at the southern capital of Thebes which were too weak to overthrow these foreigners. Their influence is noted in the importation of the composite bow, chariotry, Canaanite words and Canaanite divinities.5

Kamose, from the rival Egyptian dynasty, began the wars of liberation against the Hyksos. He is considered the last of the XVIIth dynasty and the brother of Amose I who is considered to be the founder of the XVIIIth and most powerful dynasty of all. Kamose was able to drive the dreaded Asiatics back into Palestine.6

Place of Israel. The period of the Hyksos is very obscure for obvious reasons. Biblical chronology, however, puts Jacob and his descendants in Egypt before the Hyksos invasion and the exodus after their expulsion. This synchronism is based on the assumption that the dates for the pharaohs are correct, and an early date for the exodus based on 1 Kings 6:1.

1 J. A. Wilson, The Burden of Egypt, pp. 37-38.

2Moscati, The Face of the Ancient Orient, p. 107.

3A. Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs, p. 109.

4Josephus, Contra Apion I, 14.

5Cf. CAH, 2,1:633-638 for a connection with the Greeks. Stubbings hypothesizes a link between Danaus, founder of the Mycenaean dynasty, and the Hyksos.

6See P. Montet, Lives of the Pharaohs, pp. 64ff., and Moscati, The Face of the Ancient Orient, pp. 109-10.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History