Do Christians Have Peace with God? A Brief Examination of the Textual Problem in Romans 5:1

Related Media“Therefore, since we have been declared righteous by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ…” —NET Bible

Like virtually all verses, Romans 5:1 can be variously translated. But apart from some minor tweaking—for example, “Since we have been justified” vs. “Having been justified” and the like—there is one substantive variation in how this verse has been translation. The main verb “we have” involves a textual variant, “let us have.” At issue is not two different translations of the same word, but two different words—or, rather, two different forms of the same Greek word. The difference in spelling is one letter (either an omicron or an omega—that is, either a short ‘o’ [o] or a long ‘o’ [ω]), but the difference in pronunciation, as far as we can tell, was nil in the first century AD.1 This is not to say the difference in meaning was nil! Spelled with an omicron, the verb is in the indicative mood—“we have peace”; spelled with the omega, the verb is in the subjunctive mood—“let us have peace.”

One can easily see how such a textual problem could come into existence. A scribe is listening while someone else is reading the manuscript to him; since the two words would be pronounced virtually identically, he has to make a choice. The question is: Which one is the original reading? And how can we know?

This particular problem requires a bit of detective work, along with some speculative historical reconstruction (which, however, we will reserve for the end of the discussion). Although some might get nervous about such an endeavor because its results are less than certain, it is important to keep in mind that to refrain from historical reconstruction is to leave a matter as something of a mystery. Often, the options left to us, when trying to reconstruct history, are as follows: (a) X is what we think happened, (b) Y is what we think happened; or (c) we don’t want to think. Certainly, there are times when it is neither prudent nor helpful to attempt a historical reconstruction. But in the case of solving textual problems, such an attempt often involves only a small pool of viable options. And though conclusions from such will by their nature be less than certain, this does not make them certainly untrue.

With this in mind, we now approach the problem. (Some of our discussion will be rather technical, but for those who have some training in Greek and textual criticism, the technical information should be valuable.) A number of important witnesses have the subjunctive ἔχωμεν (“let us have”) for ἔχομεν (“we have”) in v. 1. Included in the subjunctive’s support are א* A B* C D K L 33 1739* lat bo and many other witnesses. But the indicative is not without its supporters: א1 B2 F G P Ψ 0220vid 1241 1506 1739c 1881 2464 and many other witnesses. If the problem were to be solved on an external basis only, the subjunctive would be given the palm. Clearly, the “A” rating (for the indicative!) in the UBS4 is overly generous.

However, the indicative is probably correct. First, the earliest witness to Rom 5:1 has the indicative (0220). Although given a probable vote in this direction (“vid”) by the editors of the standard critical texts, this is due to the fact that the fragment is shorn right in the middle of the letter in question. An examination of the manuscript, with attention to how the scribe shaped his omicrons and omegas, indicates that the letter could only be an omicron. Second, the first set of correctors is usually of equal importance with the original hand. This is because the first corrector would have usually been the same scribe or someone else in the scriptorium, looking over the MS before it was sold. He would examine it against its exemplar and make corrections, often if not usually in the direction of that exemplar. This is not always the case, of course. But in light of the fact that the earliest witness to this textual problem had the omicron and that אis in dispute suggests that in this case we should probably listen to the voice of the corrector. Hence, א1 should be given equal value with א*. Third, there is a good cross-section of witnesses for the indicative: Alexandrian (in 0220, א1 1241 1506 1881 et alii), Western (in F G), and Byzantine (noted in the Nestle text as pm—that is, the Byzantine text is split, half reading for the indicative and half reading for the subjunctive). Thus, although the external evidence is strongly in favor of the subjunctive, the indicative is represented well enough that its ancestry could easily go back to the original.

Turning to the internal evidence, the indicative gains much ground. First, the variant was more than likely produced via an error of hearing (since, as we mentioned earlier, omicron and omega were pronounced alike in ancient Greek). But it is doubtful that such was produced by early scribes in scriptoria. This is due to two things: (1) In the earliest period of copying, most manuscripts were not done professionally in a scriptorium. Rather, they were copied by individuals who simply wanted a copy of the scriptures. Thus, presumably they would be done predominantly by sight. Since both readings evidently existed at the very earliest stages, the variant was evidently not created in a scriptorium. (2) Even the later Christian scriptoria do not show nearly as much evidence for errors of hearing as is generally supposed. That is, they do not suggest an error of hearing between the lector and scribe (although of course scribes would read to themselves). Exploitations of various scriptoria by Lake, Blake, New and others show that the extant manuscripts were not directly related to each other. This means that each scribe apparently worked at a desk, with an exemplar MS in front of him, rather than in a ‘classroom’ listening to the scripture being read.

So what is to account for the error of hearing? Evidently it was produced when Paul’s amanuensis or secretary (in this case, Tertius—cf. Rom 16:22) misheard what the author, Paul, had said. Confirmation of this is the fact that even in classical Greek omicron and omega were pronounced alike. Thus, unlike many other so-called errors of hearing which could only have occurred in later Greek (because the phonological system was evolving), this instance looks to be at the earliest stage of development. This, of course, does not indicate which reading was original—just that an error of hearing produced one of them.

In light of the indecisiveness of the transcriptional evidence (what a scribe would be likely to have produced), intrinsic evidence (what an author would be likely to have written) could play a much larger role. This is indeed the case here. First, the indicative fits well with the overall argument of the book to this point. Up until now, Paul has been establishing the “indicatives of the faith.” There is only one imperative (used rhetorically) and only one hortatory subjunctive—the “let us” exhortations—up till this point (and this in a diatribal quotation), while from ch. 6 on there are sixty-one imperatives and seven hortatory subjunctives. Clearly, an exhortation would be out of place in ch. 5. Second, Paul presupposes that the audience has peace with God (via reconciliation) in 5:10. This seems to assume the indicative in v. 1. Third, as Cranfield notes, “it would surely be strange for Paul, in such a carefully argued writing as this, to exhort his readers to enjoy or to guard a peace which he has not yet explicitly shown to be possessed by them” (Romans [ICC] 1.257). Fourth, the notion that εἰρήνην ἔχωμεν can even naturally mean “enjoy peace” is problematic—yet this is the meaning given to the subjunctive by virtually all who consider the subjunctive to be original. This point is elaborated on below.

The subjunctive here has often been translated something like, “Let us enjoy the peace that we already have.” Only rarely in the NT does the verb mean “enjoy” (cf. Heb 11:25), and it probably never has this as a primary force in the subjunctive. Thus, if the subjunctive were original, it probably would mean “let us come to have peace with God,” but this notion is entirely foreign to the context, particularly to the fact that justification has already been applied. As for the rest of the NT, the subjunctive of ἔχω occurs 44 times. John 10:10 comes close to the idea of “enjoy,” but the connotation of enjoyment is not in the verb but in περισσόν (“abundantly”). Note also John 16:33 (εἰρήνην ἔχητε [“you might have (enjoy?) peace”]), but the parallel in the second part of the verse does not help (ἐν τῷ κόσμῳ θλῖψιν ἔχετε [“in the world you have tribulation”), for otherwise Jesus would be saying that his disciples “enjoy tribulation”! Likewise, John 17:13; 2 Cor 1:15; 1 John 1:3 have similar glitches. Elsewhere the subjunctive (even present subjunctive) nowhere seems to suggest the enjoyment of something already possessed. For example, in John 5:40, Jesus in speaking to unbelievers (note v 38) says, “You do not want to come to me that you might have (ἔχητε) life.” This cannot mean “that you might enjoy the life you already have,” for then Jesus would not be offering life absolutely, but only the enjoyment of it (a contradiction of what he says in John 10:10, where both life and the enjoyment of it are granted by him)! Thus, if enjoyment is part of the connotation, so is acquiring it. (Compare further Matt 17:20; 19:16; 21:38; John 3:16; 6:40; 13:35; Rom 1:13; 15:4; 1 Cor 13:1-3; 2 Cor 8:12; Eph 4:28; Heb 6:18; Jas 2:14; 1 John 2:28.)

The point of the preceding paragraph is simply this: if the subjunctive ἔχωμεν is what Paul wrote in Romans 5:1, then the meaning almost certainly would be “Since we have been justified by faith, let us acquire so as to enjoy peace with God.” To my knowledge, no commentator who takes the subjunctive to be original would argue that this is the meaning; yet, on a linguistic basis, there seems to be no easy way around this.

In summary, although the external evidence is stronger in support of the subjunctive, the internal evidence points to the indicative. In conclusion, it might be helpful (finally) to attempt something of a historical reconstruction. Although not necessary to come to a decision about the textual problem, one may nevertheless legitimately ask, “How could the subjunctive end up having such overwhelming external support?”

Our suggestion, although speculative, fits the data well.2 Tertius, Paul’s amanuensis, may have anticipated Paul altering his course at the beginning of chapter 5. Paul’s characteristic οὖν (“therefore”) is often used to gather up the preceding indicatives and use them as the basis for action. It would have been a natural thing to anticipate after the phrase, “therefore, having been justified by faith,” some sort of command. At this juncture, Tertius naturally heard ἔχωμεν. But the letter did not go out that way. Paul’s custom was to look over his letters before sending them on to the churches. He would have corrected the subjunctive before the manuscript was sent.3 Once it arrived in Rome, the Christians there would have made copies and sent them on to other churches. Each church apparently had its own practices: some would keep the original and send copies; others would keep a copy and send the original for copying. In the process, it is probable that the original was copied frequently, but that scribes did not realize that the correction at 5:1 was the author’s. Hence, they would retain the subjunctive. In this instance, the original seems to have been copied fairly extensively without the copyist recognizing that is was Paul who corrected Tertius’ error (how could they discern his handwriting from just one letter, especially if that letter was an ‘o’?). Thus, most copyists would naturally retain the subjunctive, thinking that Paul’s omicron belonged to an overzealous scribe, not the author. But the fact that 0220 (the earliest manuscript for Rom 5:1) has the indicative suggests that it may have come from one of the early copies which Tertius was able (at least indirectly) to comment on, to the effect that the indicative was correct. Obviously, this is quite speculative. But it fits the known facts of what churches and scribes did. As a final note, it should be mentioned that the canon of the harder reading is nullified when one of the readings was patently an unintentional creation. Thus, although the subjunctive is the harder reading, since it can easily be explained as arising unintentionally, this canon cannot be applied with conviction in this instance.

Epilogue

Do Christians have peace with God? The answer is an emphatic ‘yes’! And why do we? Because we have been declared righteous by faith. The implications of this for the Christian life are vast: We ought not to wait around for the other shoe to drop, thinking that the Almighty is sitting on his throne, just waiting to pounce on us! The great truth of the gospel is not that at the moment when we embraced Christ as our Savior we were completely changed, but rather, that at that moment we were completely forgiven. And because of that forgiveness, we now have peace with God—a peace that can never be taken away. Further, as Paul goes on to elaborate in Romans 5-8, because we have this peace with God, we now can grow in grace. In other words, since we have been completely forgiven, we now have the potential to be changed into the likeness of God’s Son.

1Most teachers of Koine Greek make a distinction between omicron and omega in pronunciation, viz., omicron is a short ‘o’ as in ‘rot’ while omega is a long ‘o’ as in ‘rote.’ Classical Greek teachers, on the other hand, generally make no distinction in pronunciation. Most scholars are agreed that in the first Christian century there was little if any difference in the pronunciation of the two letters. (Thus, the Koine pronunciation may be somewhat artificial, owing more to pedagogical/phonetic causes than historical.)

2Indeed, an embryonic form of this suggestion is already mentioned by Metzger in his Textual Commentary; he suggests that Tertius created the subjunctive reading, but leaves it at that.

3Note that in 2 Thess 3:17 he indicates that at the end of all his letters he takes the pen from the amanuensis and writes a note to the readers (sometimes with his name attached, sometimes not). The purpose of such a gesture was to show that such letters were authentic and therefore authoritative. If so, then Paul was also taking responsibility for the contents and, as such, must surely have read the contents and made corrections before the document was sent out.

Related Topics: Comfort, Soteriology (Salvation), Textual Criticism, Theology Proper (God)

Junia Among the Apostles: The Double Identification Problem in Romans 16:7

Related MediaIn Rom 16:7 Paul says, “Greet Andronicus and Junia(s), my compatriots and my fellow prisoners. They are well known to [or prominent among] the apostles, and they were in Christ before me.” There are two major interpretive problems in this verse, both of which involve the identification of Junia(s). (a) Is Junia(s) a man’s name or a woman’s name? (b) What is this individual’s relation to the apostles?

Is “Junia(s)” Male or Female?

If ᾿Ιουνιαν should have the circumflex over the ultima ( ᾿Ιουνιᾶν) then it is a man’s name; if it should have the acute accent over the penult ( ᾿Ιουνίαν) then it is a woman’s name. For help, we need to look in several places. First, we should consider the accents on the Greek manuscripts. This will be of limited value since they were not added until the ninth century to the NT manuscripts. Thus, their ability to reflect earlier opinions is questionable at best. Nevertheless, they are usually decent indicators as to the opinion in the ninth century. And what they reveal is that ᾿Ιουνιαν was largely considered a man’s name (for the bulk of the MSS have the circumflex over the ultima).1

Second, somewhat contradictory evidence is found in the church fathers: an almost universal sense that this was a woman’s name surfaces—at least through the twelfth century. Nevertheless, this must be couched tentatively because although at least seventeen fathers discuss the issue (see Fitzmyer’s commentary on Romans for the data), the majority of these are Latin fathers. The importance of that fact is related to the following point.

Third, another consideration has to do with the frequency of this word as a man’s or a woman’s name. On the one hand, no instances of Junias as a man’s name have surfaced to date in Greek literature, while at least three instances of Junia as a woman’s name have appeared in Greek. Further, Junia was a common enough Latin name and, since this was Paul’s letter to the Romans, one might expect to see a few Latin names on the list. But even the data on this score can be deceptive, for the man’s name Junianas was frequent enough in Latin and Greek writings (and, from my cursory examination of Latin materials, the nickname Iunias also occurred as a masculine name on occasion2). What still needs to be examined is the control group: that is, are the other nicknames found in the NT (such as Silas, Epaphras) all exampled in extra-biblical literature? I don’t know the answer to that; to my knowledge no one has done an exhaustive search of the data for all the names of people in the NT (though Lampe has done something fairly close to this, but I have not yet seen his work on “Roman Christians”). In the least, the data on whether ᾿Ιουνιαν is feminine or masculine are simply inadequate to make a decisive judgment, though what minimal data we do have suggests a feminine name. Although most modern translations regard the name as masculine, the data simply do not yield themselves in this direction. And although we are dealing with scanty material, it is always safest to base one’s views on actual evidence rather than mere opinion.3

What is Junia’s Relation to the Apostles?

Although the vast bulk of commentaries and translations regard Junia(s) to be one of the apostles (in a non-technical sense), such a view is based on less than adequate evidence. At present, I am involved in a search of the key term in Romans 16:7 that would help us decide this issue—ἐπίσημος. Using the TLG database (which now incorporates all Greek literature from Homer to AD 600 and most Greek literature from AD 600 to 1453), as well as the PHI CD of Greek non-literary papyri, we are able to scan over 100 million words of Greek. Not all of the relevant materials have yet been translated, but of what has a certain pattern has developed.

At issue is whether we should translate the phrase in Romans 16:7—ἐπίσημος ἐν τοῖς ἀποστόλοις—as “outstanding among the apostles” or “well known to the apostles.” Although almost all translations assume the first rendering, this is by no means a given. Even in a meticulous commentary such as Fitzmyer’s, though both options are discussed, no evidence is supplied for either. But the evidence is out there; mere opinion is inadequate.

In order to resolve this issue two items need to be examined. First is the lexical field of the adjective ἐπίσημος. Second is the the syntactical implication of this adjective in collocation with ἐν plus the dative.

First, for the lexical issue. ἐπίσημος can mean “well known, prominent, outstanding, famous, notable, notorious” (BAGD 298 s.v. ἐπίσημος; LSJ 655-56; LN 28.31). The lexical domain can roughly be broken down into two streams: ἐπίσημος is used either in an implied comparative sense (“prominent, outstanding [among]”) or in an elative sense (“famous, well known [to]”).

Second, the key to determining the meaning of the term in any given passage is both the general context and the specific collocation of this word with its adjuncts. Hence, we turn to the ἐν τοῖς ἀποστόλοις. As a working hypothesis, we would suggest the following. Since a noun in the genitive is typically used with comparative adjectives, we might expect such with an implied comparison. Thus, if in Rom 16:7 Paul meant to say that Andronicus and Junia were outstanding among the apostles, we might have expected him to use the genitive4 τῶν ἀποστόλων. On the other hand, if an elative force is suggested—i.e., where no comparison is even hinted at—we might expect ἐν + the dative.

As an aside, some commentators reject such an elative sense in this passage because of the collocation with the preposition ἐν,5 but such a view is based on a misperception of the force of the whole construction. On the one hand, there is a legitimate complaint about seeing ἐν with dative as indicating an agent , and to the extent that “well known by the apostles” implies an action on the apostles’ part (viz., that the apostles know) such an objection has merit.6 On the other hand, the idea of something being known by someone else does not necessarily imply agency. This is so for two reasons. First, the action implied may actually be the passive reception of some event or person (thus, texts such as 1 Tim 3:16, in which the line ὤφθη ἀγγέλοις can be translated either as “was seen by angels” or “appeared to angels”; either way the “action” performed by angels is by its very nature relatively passive). Such an idea can be easily accommodated in Rom 16:7: “well known to/by the apostles” simply says that the apostles were recipients of information, not that they actively performed “knowing.” Thus, although ἐν plus a personal dative does not indicate agency, in collocation with words of perception, (ἐν plus) dative personal nouns are often used to show the recipients. In this instance, the idea would then be “well known to the apostles.” Second, even if ἐν with the dative plural is used in the sense of “among” (so Moo here, et alii), this does not necessarily locate Andronicus and Junia within the band of apostles; rather, it is just as likely that knowledge of them existed among the apostles.

Turning to the actual data, we notice the following. When a comparative notion is seen, that to which ἐπίσημος is compared is frequently, if not usually, put in the genitive case. For example, in 3 Macc 6:1 we read Ελεαζαρος δέ τις ἀνὴρ ἐπίσημος τῶν ἀπὸ τής χώρας ἱερέων (“Eleazar, a man prominent among the priests of the country”). Here Eleazar was one of the priests of the country, yet was comparatively oustanding in their midst. The genitive is used for the implied comparison (τῶν ἱερέων). In Ps Sol 17:30 the idea is very clear that the Messiah would “glorify the Lord in a prominent [place] in relation to all the earth” (τὸν κύριον δοξάσει ἐν ἐπισήμῳ πάσης τῆς γῆς). The prominent place is a part of the earth, indicated by the genitive modifier. Martyrdom of Polycarp 14:1 speaks of an “outstanding ram from a great flock” (κριὸς ἐπίσημος ἐκ μεγάλου). Here ἐκ plus the genitive is used instead of the simple genitive, perhaps to suggest the ablative notion over the partitive, since this ram was chosen for sacrifice (and thus would soon be separated from the flock). But again, the salient features are present: (a) an implied comparison (b) of an item within a larger group, (c) followed by (ἐκ plus) the genitive to specify the group to which it belongs.7

When, however, an elative notion is found, ἐν plus a personal plural dative is not uncommon. In Ps Sol 2:6, where the Jewish captives are in view, the writer indicates that “they were a spectacle among the gentiles” (ἐπισήμῳ ἐν τοῖς ἔθνεσιν). This construction comes as close to Rom 16:7 as any I have yet seen. The parallels include (a) people as the referent of the adjective ἐπίσημος, (b) followed by ἐν plus the dative plural, (c) the dative plural referring to people as well. All the key elements are here. Semantically, what is significant is that (a) the first group is not a part of the second—that is, the Jewish captives were not gentiles; and (b) what was ‘among’ the gentiles was the Jews’ notoriety. This is precisely how we are suggesting Rom 16:7 should be taken. That the parallels discovered so far8 conform to our working hypothesis at least gives warrant to seeing Andronicus’ and Junia’s fame as that which was among the apostles. Whether the alternative view has semantic plausibility remains to be seen.

In sum, until further evidence is produced that counters the working hypothesis, we must conclude that Andronicus and Junia were not apostles, but were known to the apostles. To be sure, our conclusion is tentative. But it is always safer to stand on the side of some evidence than on the side of none at all.

This, however, should not be the end of the matter. We welcome any and all evidence that either supports or contradicts our working hypothesis. After all, our objective is to pursue truth.

1 Although some might suspect a chauvinistic motive on the part of the scribes, this assumes that all scribes were men. A recent doctoral dissertation done at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, has demonstrated otherwise.

2 This tentative conclusion is contradicted by older studies that are presently inaccessible to me. Nevertheless, the database I am using is the CD from the Packard Humanities Institute, certainly more comprehensive than anything examined previously.

3 The NET Bible regards this as a woman’s name because the data are sufficient to argue this way, while they are insufficient to argue that it is a man’s name.

4 Either the simple genitive, or one after the preposition ἐκ.

5 Moo, for example, writes: “if Paul had wanted to say that Andronicus and Junia were esteemed ‘by’ the apostles, we would have expected him to use a simple dative or ὑπό with the genitive” (D. J. Moo, Romans, NICNT, 923).

6 Cf. Wallace, Exegetical Syntax, 163-66, where it is indicated that the only clear texts in the NT in which a dative of agency occurs involve a perfect passive verb; in the discussion of ἐν with dative, it is suggested that there are “no unambiguous examples” of this idiom.

7 But in the Additions to Esther 16:22 we read that the people are to “observe this as a notable day among the commemorative festivals” (ἐν ταῖς ...ἑορταῖς ἐπίσημον ἡμέραν). In this text, that which is ἐπίσημος is itself among (ἐν) similar entities. Whether this normally or even ever happens with personal nouns in the plural after ἐν is a different matter, and one that cannot be answered until further research is conducted.

8 To be sure, much more work needs to be done. All of TLG and PHI #7 need to be searched for the construction. Nevertheless, the evidence thus far adduced falls right in line with our working hypothesis.

Related Topics: Text & Translation

The Lord is My Shepherd

Related MediaEditor’s Note: Ruqaya’s stirring testimony speaks eloquently to the power of the gospel. This young lady grew up as a Muslim, but put her faith in Jesus Christ a few years ago. Her testimony is somewhat reminiscent of Paul’s Damascus Road experience. I know her well, and can affirm the truth of this testimony. My prayer is that her words here will drive deep and convict many of her Arab countrymen of their need of the Savior. You are sure to hear more of “Rockie’s” devotion to Christ in the years to come. Rockie, may God grant you opportunity and boldness in your witness to the Lord Jesus Christ.

Daniel B. Wallace,

August 1, 2003

It was February 10, 1990 on a Saturday when I sat at the airport at the age of 23. I thought about what happened in my past life, what is happening to me now, and what could happen to me in the future. My plane to Jordan would leave in an hour and my life would never be the same. I would marry a man whom my father chose for me and I would never return to the U.S. unless my husband decided to move here.

You see, I was born in Jordan to a Palestinian family. As the third and middle child, my grandmother decided I should be the first of my brothers and sisters to carry a Muslim name. She named me Ruqaya, after one of the messenger Mohammed’s daughters. When I was eight years old, my father decided to come to the U.S. to make some money and eventually go back to Jordan. He feared his daughters would grow up to become American women and possibly even marry American men. My father held very strongly to his Arab customs and wanted his children to follow the Arab customs and Islam, especially his daughters. It is a disgrace to the family and forbidden in Islam for an Arab Muslim woman to marry a non-Muslim man. On the other hand my brothers were allowed to marry anyone they wanted as long as they are believers of the Books (Torah and Gospel) because Islam gave them that right. That is why my father sent me to Jordan to go to high school.

I lived with my grandmother, my uncle, and his family for a few years. My father was so pleased with me because I became a devout Muslim. He was relieved to know he didn’t have to worry about my older sister because she was already married to an Arab Muslim, my younger sister was too young for him to worry about, and I was living the life that would please God and him. I stayed in Jordan as my dad traveled back and forth from Jordan to the U.S. so he can visit me while I was going to school. As much as I loved seeing him, I felt happy living in Jordan and following God’s ways. I prayed five times a day, fasted the month of Ramadan, read the Qur’an daily, wore the veil (covering the entire body and showing only the hands, face and feet) and tried to imitate the prophet Mohammed in every way. No matter what I did for God, I felt I needed to do more to show him how obedient I was to Him. I would sit with my relatives and start quoting the prophet Mohammed and the Qur’an to them. My father was so proud of me!

The more I spent time in Islam, the further I drifted from God. The Muslims I knew didn’t seem to truly love God. They worshipped Him to obtain heaven and feared His wrath and anger. I also began to wonder about my motive in following Islam. “Was I following it for God or for the people around me?”, I thought to myself. I’m not sure what my answer was, but I decided not to wear the veil anymore and act like a Muslim instead of looking like one. Worshipping God suddenly became an issue only between God and me.

At the age of twenty three, my father decided I should be married. In the Arab culture, the marriage process required a man asking for a woman’s hand from her family. Dating is not allowed, but both have a chance to talk to each other in the presence of their families before they decide if they are right for each other. Several Arab Muslims came to ask for my hand, but I refused. I had a hard time marrying someone that I didn’t know just to please my father. The culture and Islam allow marriages between first cousins. I refused to marry my cousin along with distant relatives and even strangers. “Why would my father want me to marry someone I didn’t love or even know?”, I felt. At the same time, my father didn’t understand why I would refuse all these good men when he knew quite well that love comes after marriage and not before. When my dad realized that reasoning with me wouldn’t work, he tried force. He decided I should go back to Jordan and stay there until I was married. My younger sister was sixteen at the time, so my dad felt she should come with me. That was a trying moment in my life.

Disgrace in the family brought by a daughter is the worst shame a family can go through. Many families have killed their daughters for what the culture considers disgrace. That was what I had to think about when I sat at the airport with my sister as we prepared to leave for Jordan. My dad flew to Jordan before us to prepare for my wedding and my brother made sure we would get to the airport without any problems. As I sat in the airport, I knew what I had to face—disgrace or misery: disgrace the family if I ran away or be miserable when married to one of my cousins for the rest of my life. At that point, I was so angry at my father and God: angry at my father for what he was doing and angry at God for allowing what was happening to me. I felt my heart screaming at God and saying, “Out of everyone in my family, it was ME who prayed to You, ME who fasted for You, ME who studied the Qur’an and this is what You allow to happen to me?! Why did You allow my family to send me to Jordan when I was still a teenager? Why did I have to live in an uncaring home? Why didn’t You help me pursue my education when my dad refused to let me continue my education? Why did You allow my grandmother, my uncle and his family to treat me so harshly when I was with them? Why did You allow all these bad things to happen to me? Why God, WHY?!” I made a decision that day to stop praying to God and stop worshiping Him the way I had done in the past.

February 10, 1990 was the day that completely changed my life. My younger sister and I took our luggage and we were on our way to the nearest hotel. The plane landed sixteen hours later as my father, along with other relatives, waited for us in the airport to greet us. When my father realized that we weren’t on the plane, he went out of his mind! He called my brother and told him we weren’t on the plane so my brother began to desperately search for us. My sister knew she had to go back home because the family would kill us both once they found us. There was a possibility they would claim I kidnapped my sister because she was under age. We both agreed she would tell them that I dragged her off the plane and forced her to come with me so they would not harm her. I promised her that if they tried to force her to do anything she didn’t want, I would come back and get her. We tearfully said good-bye to one another thinking that we would never see each other again.

God alone was the only One who could protect me, but I was so angry at Him that I didn’t ask for His help. I didn’t have much money and I couldn’t work because they would find me under my social security number. I didn’t have many American friends because my father wouldn’t allow me to be influenced by their “Satanic ways.” And more importantly, I didn’t know what to do in a society I hardly associated with. I needed courage, strength and wisdom.

I joined the U.S. Army National Guard so the government could protect me. Once I was done with my military training, I went back to a suburb in the city where my family lived and I lived there in hiding. During that time, I found a job and became very successful at work. I rented an apartment from the money I saved while I was on active duty in the military, and met many friends that would care for me as if I was a member of their family.

Four years later, I slowly began to contact my family. My father had moved to Jordan and married another woman there, my brothers were living on their own, and my mom and younger sister were living together. After five years, I made peace with my family and they accepted me living alone and running my own life. It amazed me to see how accepting my family was of that; I began to see God’s grace in my life. “He didn’t neglect me after all,” I thought, “I don’t know what I would have done without His love and grace. He took me out of a bad situation to put me in a better one. He protected me and gave me the courage, wisdom and strength to survive on my own.” I felt ashamed for being angry at Him and I needed to make peace with Him by going back to Islam. I didn’t pray five times a day, but I thanked Him daily and did nice things that I thought would please Him.

February of 1998, I accepted a job for a company that would move me to another state to work as a salesperson. That same month a dear friend of mine died of a car accident leaving me in agony and distress. Because I had made peace with God, I was able to talk to Him and for the first time have conversations with Him. I didn’t know why He did what He did, but I had to accept it because of my past experience, I knew He did things for a reason even though I didn’t understand. Nonetheless, I asked for His help, and actually asked Him to help everyone in the world who needs help.

The month of May had arrived and it was time for me to move. I arrived not knowing anyone or what to expect from this city. I was scared being in a new city, and sad that I left my family and friends, but excited about my new job. I wanted to be close to Mexico so I could learn more Spanish and travel there for my company. My plan was to be successful in international sales, but the Lord had other plans for me.

Under the strangest circumstances, I met a woman one evening that was walking her dog in front of my apartment. She and I became friends instantly so one day she invited me to go to her church. I didn’t think there was any harm in me going to church. “After all,” I thought, “God sent down Judaism and Christianity so He would not be upset if I went to church even though I’m a Muslim.”

I really enjoyed the pastor’s sermons and felt that he offered sound teachings. The only thing that didn’t seem sound to me was when the pastor talked about Jesus being the Son of God. I felt, though, that God would forgive the pastor because he was misled by his family to believe that Jesus is the Son of God. Sometimes the pastor would say that Jesus is God in the flesh and sometimes he would say that Jesus is the Son of God. I knew for sure that the pastor was obviously confused because how can Jesus be God and then be God’s Son? That just didn’t make any sense to me. I continued to go to church until one day the pastor said that Muslims didn’t know Jesus Christ. I was struck by that comment. Something inside of me said, “Of course Muslims know Jesus; the pastor is sadly mistaken and I need to set the record straight.” After the service, I went to the pastor, introduced myself to him, and told him that I’m a Muslim and I DO know Jesus Christ. He apologized for making a blanket statement, and said, “ I know that Muslims believe he is a prophet.” I told him that I would like to meet with him to talk about his faith. Sooner or later I would have approached the pastor, but that comment expedited the whole process for me to search for the truth. That was another turning point in my life.

My heart and soul were convinced that the prophet Mohammed was the last messenger and the Qur’an was the last book sent by God. The Qur’an clearly states that Jesus was a messenger who was born of a virgin mother, Mary. He had many miracles including bringing the dead to life, healing the sick, speaking when he was a baby, and creating a bird out of clay. The Lord loved him so much that when his enemies were preparing to crucify him, God sent someone to look like Jesus and die on the cross instead of Jesus. Muslims believe that he never died, but was raised to heaven to be protected from his enemies. Jesus, in the Qur’an, claims he never told anyone to worship him but to worship the One true God. The Bible has been changed, according to Muslims, so that Christians and Jews really don’t have the true Books. When God gave Mohammed the message, God preserved the Qur’an and made sure no one would change it like the Torah and the Gospel.

I continued to go to Church and listen to the pastor’s sermons, but I began to wonder why Christians had different beliefs than Muslims. As I listened and began to read different books on Christianity and Islam, I became very confused and didn’t know what to believe anymore. I had to wrestle with many issues: Was Jesus crucified? Did Jesus die on the cross for man’s sins? Is Jesus God or the Son of God? Is God a Triune God? Is the Bible really accurate and had the Bible been preserved after all these years? If the answer was yes to all my questions, that would mean then that Mohammed was a liar and the Qur’an was not from God. Work, family, friends, and everything else around me suddenly became meaningless. My days and evenings were consumed with tears and agony over God and the truth. How could I know what really happened 2,000 years ago? How could I betray my family or maybe even God if I believed in Jesus Christ? That was a decision I was not willing to make myself. Nonetheless, I continued to read and search for answers to all my questions.

My questions needed convincing answers and I didn’t know who would help me until the pastor recommended a professor at a seminary. As I spoke with the professor and read many books, things started making sense. The Bible had to be accurate because of the Dead Sea Scrolls. One of the Dead Sea Scrolls was a copy of the book of Isaiah that dates back to 125 BC. Apart from the Dead Sea Scrolls there are also parts of very old manuscripts of the Gospel according to John and the Gospel according to Matthew that we currently have that are in museums around Europe and the Middle East. I began to read and compare the prophecies that were in the Old Testament about the coming of the Messiah and how they were all fulfilled in the New Testament. The Old Testament talks about the Messiah’s hands and feet being pierced for man’s transgressions, he would be born of a virgin mother, he would be led like a lamb to the slaughter, he would be sold for 30 pieces, he would enter Jerusalem on a donkey, and he would be called the Almighty God and Prince of Peace. These prophecies in the Old Testament and how they were fulfilled in the New Testament led me to believe in the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. The only thing left for me to wrestle with was Jesus’ deity as part of a Triune God. “I can not, under any circumstances, believe that Jesus is God; that would be pure blasphemy!”, I thought to myself. I had to either end my search or challenge Jesus’ deity because I knew I couldn’t embrace Christianity if I knew I had to believe in Jesus’ deity. I needed a miracle.

One day I said to Jesus, “O.K. Mr. Messiah, it’s my way or the highway. If you are God, you would prove it to me by doing what I want you to do.” Jesus didn’t respond. I was beginning to believe that God didn’t want me to trust in Jesus because I thought for sure He’d respond to my prayers. Then one Sunday, I went to church and the pastor was talking about prayer. He said, “When I pray for something, I usually say: God, if this is Your will, then open the door wide open or slam it shut, but please Lord, don’t let me make this decision myself.” I felt good about that prayer because I was afraid of making the wrong decision about God. As soon as I got home that day I prayed and said, “God, if you want me to follow Christianity, then open the doors wide open or slam it shut, but please Lord let me make this decision myself.” For a whole week nothing happened.

Sunday morning August 2, 1998, I woke up feeling depressed as usual about my search. I decided not to go to church because I didn’t want to hear people say that Jesus is God anymore. An Iranian Christian pastor called me and said he would like a Qur’an. That evening, I went to his church to give him a Qur’an because I thought it was a nice thing to do. He knew I had been searching for a few months. When I arrived at church, he asked me where I was in my search. I told him that I believed in the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, but I didn’t believe in his deity. I also told the Iranian pastor that I’ve studied the life of Jesus, I would want a man like him to be my neighbor, my brother, my father, by boss, my judge in a court of law, my king in a country because no one in history compared to him. He said, “Well, if you think he is that wonderful and that he died on the cross for your sins, will you confess that before God?” I agreed so we prayed together and he told me he would like to be the first person to shake my hand and congratulate me for being one of God’s children. He asked me to continue to pray, read the Bible daily, and tell everyone what I just did. I had no idea what he was talking about. The pastor and I said good-bye to one another and I headed for my car. I got in my car and it all hit me. I sat there in total shock and said out loud as if God was sitting right next me, “You really wanted me to do this all along didn’t You? You really wanted me to take this step, didn’t You?” I then began to cry because I realized what happened. God made the decision for me! I fought with Jesus and I lost! I wanted him to reveal himself to me on my terms, but he was willing to reveal himself to me on His terms. It was clear to me that Jesus wanted me to walk with him instead of challenge Him.

I am grateful that the Lord has been my shepherd throughout my life. He has been there for me when I needed Him and even when I thought I didn’t need Him. He has taken me through roads and routes I never dreamed to take. Above all, I’m amazed and that He loved me so much, He sent Jesus do die on the cross for me! How humbling and precious that is to me! The Lord is my shepherd and He has been leading His sheep.

Related Topics: Evangelism, Soteriology (Salvation)

Is No Place Safe Any More? (Or, Where Is God in the Midst of Tragedy?)

Related MediaHeadline for the Dallas Morning News, Friday, September 17, 1999: Why? The thick black letters are an inch and a half high. They ask the question that has been haunting the country since the Wednesday before, when Larry Gene Ashbrook walked into Wedgwood Baptist Church in Forth Worth and in the space of five minutes killed seven young people, injured seven others, then turned the gun on himself and took his own life.

Comparisons with the Columbine High School shooting on April 20, in which 15 were killed (including the two gunmen) immediately come to mind. A common refrain heard on the nightly newscasts was, “First a school, then a church! Is no place safe any more?” Maybe the ‘Why?’ should have been two inches high.

Anyone with an ounce of humanity in him struggles with this question. Easy answers only come forth, it seems, from insensitive folk who prefer to distance themselves from the tragedy. Asked by my pastor, Pete Briscoe, to write up something of a theological perspective on this horrific event, I found myself procrastinating. And procrastinating. What could I possibly say that could offer any comfort?

One of the dangers of offering a theological perspective is that it can look cold and calculating, insensitive to the unspeakable pain that survivors, relatives, and friends are going through. It can look no different than so many politicians’ speeches that are simply hollow rhetoric. So I must preface my remarks with this: I weep with you. I grieve with you. And although I can’t possibly know what you’re going through, my heart aches for you.

John Piper put it well: “Pain is life’s greatest hermeneutic.” By that he meant that it is often only through pain that we can see all the pieces of the puzzle, that we have the big picture of what life is all about laid out so clearly in front of us, that we can finally understand. But pain does not automatically do this: our response to pain does—and even then, not immediately. Atheists and saints are both often ‘born’ in the aftermath of a tragedy.

When we ask, “How could God let this happen?”, we are on to something. What we do and feel next is of utmost importance. Some people decide that it is blasphemous even to raise such a question in the first place, that to ask ‘Why?’ is itself sinful. I do not share that sentiment, for this reason: it is neither human nor biblical. The books of Job and the Psalms ask this question at least sixty times—almost regardless of which translation one reads—and a very large portion of these questions are on the lips of godly men as they wonder about God’s ways. It is no sin to ask why. Indeed, I think it may well be wrong not to ask that question! When our son nearly died from cancer a few years ago, some friends consoled with this kind of attitude. They comforted us by quoting precious verses—especially Romans 8:28 (“All things work together for good for those who love God…”)—and then they walked away. Scripture became for them a way to deny the grief, to deny the pain. They loved us at an arm’s distance. To be sure, in the midst of suffering the human soul cries out for answers. But it cries out for more than that. It cries out for comfort, for love, for someone to share the burden of grief.

All of this is not to say there are no answers. But the answer that we seek is too often elusive; we never really know in this life—we cannot know in this life—the details of the answer to our question. Now, to be sure, we sometimes do get a partial answer to the ‘Why?’ As Pete preached last Sunday, a huge part of God’s purpose is to make his Son known. He gave eloquent testimony to the fact that God had done just this. The response of Christians around the country to the tragedy at Wedgwood Baptist Church was overwhelming: renewed commitments, greater boldness for Christ, and opportunity to speak of our confident hope of the resurrection because Jesus paid the price for our sins. All this in a matter of days. And if that were not enough, the cover story of this last week’s Christianity Today (dated October 4) was “’Do You Believe in God?’ How Columbine Changed America.” If we wonder about the impact that the Fort Worth shooting might have, sit down and read this CT article by Wendy Murray Zoba. She chronicles how three teenagers—Rachel Scott, Val Schnurr, and Cassie Bernall—affirmed their belief in God before getting shot. One of the kids in Cassie’s youth group later confessed, “Cassie raised the bar for me and my Christianity.” In Rachel’s journal there is an earnestness about her faith, reminiscent of Jim Elliott: “I want heads to turn in the halls when I walk by. I want them to stare at me, watching and wanting the light you put in me. I want you to overflow my cup with your Spirit…. I want you to use me to reach the unreached.” God answered her prayer! Her father relates,

Columbine was a wound to open up the hearts of the kids in this country. Tens of thousands of young people have given their hearts to the Lord [since Columbine]; we know that from phone class and letters. Organized Christianity hasn’t been able to do that in decades.”

And make no mistake about it: Columbine and Wedgwood are related: Cassie Bernall’s mother offers this insight:

Most of the kids they killed—if not all of them—were Christian kids. …

It was spiritual warfare. It’s still happening. At Cassie’s memorial there was a happy-face balloon, and our son discovered someone had drawn a bullet going into it. And there was a young man walking in the mall wearing a black trench coat with a T-shirt that said, “We’re still ahead 13 to 2.”

Whether we will ever know what was in Larry Ashbrook’s mind when he gunned down the kids at Wedgwood Baptist Church, we can be assured that behind him stood the forces of Beelzebul, of Satan himself. If six months after the Columbine slaughter America has already started to rouse from its spiritual slumber, what will happen six months from now? Maybe not only will unbelievers turn to Christ, but believers might strengthen their commitment to the Lord who bought them and jettison the shell of cultural Christianity that their faith has become.

But what if that doesn’t happen? What if this country simply goes back to sleep, as though the whole thing were simply a bad dream, a mere blip in an otherwise peaceful slumber. What if the responses are merely ethical and not spiritual? What if people clean up their lives but don’t turn to Christ—resulting in the same eternity reserved for the worst of unrepentant sinners? If such were the case, would God’s purposes be thwarted? NO. But our answers to such tragedies would continue to lack the details that we had hoped for.

So what answer can we know? I’ll get to that in a moment.

As I said, we are on to something when we start by asking God why there is evil in the world. When evil gets a face, when it becomes personal—as it inevitably does in everyone’s life—the question becomes more earnest, more desperate. At bottom, what we are really asking is a question about the nature of God. When someone asks, “How could God let this happen?” two things are presupposed about God: he is good and he is sovereign. And therein lies the crux of the problem. If we think about it a little while, we might even articulate it this way, “If God is good, isn’t he also powerful enough not to have let this happen?” Or, put another way, “If God is in control, isn’t he good enough not to have let this happen?” Either way, the goodness of God or the sovereignty of God seems to be on trial. Perhaps you can see why atheists are born at a time like this: their image of God is shattered at the paradox of the situation. “God wasn’t there for me” becomes the mantra that leads to atheism or, in the least, to a marginalization of God in one’s thinking. The scary thing is that we are all atheists at heart when we sanitize and shrink-wrap the majesty and grandeur of God into manageable proportions.

Briefly, I wish to address the issue of two of God’s attributes, his sovereignty and his goodness, and how they relate to one another. Consider the following points.

(1) When we think of God’s will we need to nuance the discussion. The Bible speaks of God’s will in essentially two ways: what he desires and what he decrees. These two must not be confused.

(2) God desires that we should not sin: “For this is the will of God, your sanctification; that is, that you abstain from sexual immorality” (1 Thess 4:3); “live the rest of the time in the flesh no longer for the lusts of men, but for the will of God” (1 Pet 4:2); “understand what the will of the Lord is—namely, do not get drunk with wine but be filled by the Spirit” (Eph 5:17-18). And yet, we do sin. If this is all there is to God’s will, then he’s not very powerful.

(3) God has decreed all that has come to pass and all that will come to pass: He “works all things according to the counsel of his will” (Eph 1:11); “I know that you can do all things and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted” (Job 42:2); “For truly in this city there were gathered together against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and the people of Israel, to do whatever your hand and your purpose predestined to occur” (Acts 4:27-28). Cf. also Isaiah 40, Romans 9-11. Yet, not all that God has decreed is good (at least not in the short run). If this is all there is to God’s will, then he must not be good himself.

(4) These two aspects of God’s will can be stated simply: God desires some things that he does not decree, and God decrees some things that he does not desire.

(5) Now, before we jump to any conclusions about the illogic of it all, we need to consider another attribute of God: simplicity. God is one (Deut 6:4); his attributes cannot be compartmentalized. There is no contradiction in him. He is eternal in his love, omniscient in his justice, good in his sovereignty, and sovereign in his goodness. He is not good one day, then sovereign the next.

Nothing catches him by surprise; not even a sparrow falls to the ground without his knowledge. Not even the Fort Worth tragedy caught God off-guard. We must not think of him as sitting on the throne, trying to keep track of all the activities on this old sphere, but every once in a rare while missing a catastrophe that somehow slips under his heavenly radar! God is not sitting there thinking, “I should have seen the signs! I should have known Larry Ashbrook was capable of doing this!” He knows all things that ever have happened, are happening, or will happen. He also knows all the ‘could haves’, ‘would haves’ and ‘should haves.’ All contingencies and realities are perfectly known to God and always have been. God doesn’t learn, precisely because he already knows all. And if he never has to look down the corridors of time to see what’s going to happen, this must mean that everything happens according to his purpose. Even the mass murder in Fort Worth.

And yet, his purpose is ultimately to glorify himself. He does this especially through his creation, particularly humanity. Ultimately, all that God does is good—perfectly, eternally, infinitely good. One of the reasons we can’t see it—or refuse to see it—is that our horizon is temporal. In modern America, we tend to interpret God’s blessings in dollars and cents, in quality of life, in conveniences and comfort. We think that what we have come to value must be what God values. But listen to the remarkable words of the apostle Paul as he sits imprisoned in Rome: “For it has been granted to you not only to believe in Christ but also to suffer for him” (Phil 1:29, NET). Paul says that suffering for Christ is a gift! In Paul’s mind, what these Christian kids in Fort Worth just went through was a privilege. If we can’t see that then perhaps our values have gotten really messed up somewhere along the road. But we also can’t see that because we tend to view this life as all there really is. But the reality is that this life—whether it lasts for two days or ninety years—is not even a speck on eternity’s time line. As one of my professors, S. Lewis Johnson, Jr., used to say, “There is an ‘until’.” What all this means is that the full goodness of God cannot possibly be known in this life.

(6) That there are no contradictions in God does not mean that there are no apparent contradictions in God. That is because what the infinite God does appears to finite creatures as impossible and contradictory. Perhaps an analogy might help. It is as though we lived in a two-dimensional world, looking out at a three-dimensional world. If in our realm of existence we saw a man walk toward us, since our only frame of reference was two dimensional we would swear that the man was growing at an incredible pace! But then, just as quickly, he shrinks when he walks away. We know that that is impossible, but we have no explanation for what we just witnessed. And frankly, we don’t have the capacity to understand what we just witnessed. But if we decide never to look past our shallow plane of existence because we can’t understand what we see, our lives are thereby impoverished by our stubbornness and ignorance.

(7) All of this leads to a final point: How do we deal with the tension between the goodness of God and the sovereignty of God? And this is the real question we are asking in the midst of tragedy. Our response is to trust. And to know that there is no contradiction in God, to actually take comfort in the fact that he is infinite and we are but puny little creatures who often sin by presuming that we can tell God how to do his job. As he says in Isaiah 55:8-9, “My ways are not your ways and my thoughts are not your thoughts. Just as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts higher than your thoughts.” Or, as the apostle Paul put it, “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how fathomless his ways! For who has known the mind of the Lord, or who has been his counselor? Or who has first given to God that God needs to repay him? For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever! Amen” (Rom 11:33-36, NET). This crescendo of praise from Paul’s pen was not conceived in an ivory tower setting. Paul magnified his God in response to his own profound grief over the unresponsiveness of the Jews to their Messiah (cf. Rom 9:1-3). His words are just as relevant and just as comforting today as they were then.

Related Topics: Cultural Issues, Theology Proper (God)

Rushdoony, Neoplatonism, and a Biblical View of Sex

Related MediaN.B. The following essay was originally an address given at the University of Arkansas in 1987.

Preface

I am unashamedly a Christian. But lest you think that I have come here today simply to say, “Fidelity in a monogamous relationship is the only way to go—all else is sin!” I want to set you at ease. I do believe that, but there are reasons for my faith. If you’re not a Christian, you may still be interested in hearing the rationale for a Christian view of sex and marriage.

As foreign as philosophy seems from a talk about sex, it is necessary to gain some philosophical underpinnings in order to view sex properly. Consequently, I will address two topics in this lecture: (1) misconceptions about the biblical view of sex and (2) what the Bible teaches about sex and marriage.

I. Misconceptions about the Biblical View of Sex: Rushdoony to the Rescue!

Contrary to popular opinion, God is not a cosmic killjoy. He is not out to ruin all our fun! Unfortunately, many people have viewed God that way for centuries. Some have even castrated themselves in alleged obedience to the divine will. In some measure, this is because Christians have promoted such a false view of God. . .

Among the many influences on Christianity almost from its inception, one of the most pernicious—and arguably the most destructive from a philosophical view—is neoplatonism. Neoplatonism is simply ‘new’ (neo) ‘Plato-(n)ism.’ It is a dialectical dualism which pits spirit against flesh, body against soul, mind against matter, etc. It crept into the church in the second century AD through the route of gnosticism. Now the gnostics were an early Christian heretical group, quite popular in Egypt, which viewed spirit as good and matter as evil. They found a difficulty accepting the biblical teaching of creation: “God created the heavens and the earth. . . and it was good.” So they posited a series of semi-creators between God and the earth. That is to say, God created the next being who was not, like God, pure spirit, but was instead an amalgam of spirit and matter (though mostly spirit). He then created the next being who had a bit more matter to his make-up. And so on down the line: the last creator created the earth, pure matter. Jesus Christ was considered very high up on the ladder—hence, the gnostics did not view him as real man.

The result of all this was that by mixing the Bible with ancient Greek philosophy, Christians began to see a dichotomy, a dialectical struggle within man, between body and soul, between emotion and reason. In reality, such a view of life was merely neoplatonism in Christian garb. Unfortunately, it has plagued Christians—as well as all of western civilization—for nearly twenty centuries. We might, with some justification, call it the ‘Spock syndrome.’ (Spock, as you well know, was the science officer of Star Trek fame: as the son of a vulcan father and a human mother, he constantly wrestled with reason vs. emotion. Any time he gave in to his human nature, Dr. McCoy was quick to point it out to him! [Incidentally, it is no accident that the very human—and emotional—McCoy was the medical officer, i.e., he dealt with bodies, while Spock was the science officer who dealt with things related to pure reason.] Although Gene Roddenberry had glamorized Spock [he was just about everyone’s favorite character], in reality a person who adopts a world-view that sees body and spirit in mortal combat is a moral monster.)

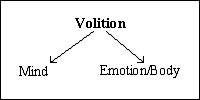

We might illustrate, rather crudely, the neoplatonic view of life:

I’d like to illustrate how extensive and pervasive this neoplatonic world-view has infected Christianity by quoting heavily from a very important book: Rousas John Rushdoony’s Flight from Humanity (Craig Press, 1973). Although this will seem somewhat pedantic, it is crucial for you who are Christians—as well as you who are non-Christians—to understand the difference between what many people believe about Christianity and what the Bible teaches.

First, Rushdoony gives some examples of how ancient Christians mixed biblical Christianity with neoplatonism:

“For a Christian, the lives of ‘the saints’ are sometimes painful reading. Intelligence and faith are sometimes wedded to the most ludicrous practices and to ideas alien to Biblical religion ... When, after a very hot journey, Jovinus washed his tired feet (and hands) in very cold water, and then stretched out to rest, the ‘holy’ Melania rebuked him:

Melania approached him like a wise mother approaching her own son, and she scoffed at his weakness, saying, “How can a warm-blooded young man like you dare to pamper your flesh that way? Do you not know that this is the source of much harm? Look, I am sixty years old and neither my feet nor my face nor any of my members, except for the tips of my fingers, has touched water, although I am afflicted with many ailments and my doctors urge me. I have not yet made concessions to my bodily desires, nor have I used a couch for resting, nor have I ever made a journey on a litter.

We learn nothing about Biblical holiness from Melania, although we do begin to realize what ‘the odor of sanctity’ could have meant.” (pp. 1-2)

“. . . the sin of Adam [was] to be as God, to transcend creatureliness with all its limitations and become more than a man. Macarius of Alexandria gives us an example of this:

Here is another example of his asceticism: He decided to be above the need for sleep, and he claimed that he did not go under a roof for twenty days in order to conquer sleep. He was burned by the heat of the sun and was drawn up with cold at night. And he also said: “If I had not gone into the house and obtained the advantage of some sleep, my brain would have shriveled up for good. I conquered to the extent I was able, but I gave in to the extent my nature required sleep.”

Early one morning when he was sitting in his cell a gnat stung him on the foot. Feeling the pain, he killed it with his hands, and it was gorged with his blood. He accused himself of acting out of revenge and he condemned himself to sit naked in the marsh of Scete out in the great desert for a period of six months. Here the mosquitos lacerate even the hides of the wild swine just as wasps do. Soon he was bitten all over his body, and he became so swollen that some thought he had elephantiasis. When he returned to his cell after six months he was recognized as Macarius only by his voice.

To attain perfection meant forsaking every evidence of creatureliness, every element of bodily desires and needs, and becoming pure spirit in a virtually dead flesh.” (pp. 3-4)

But lest we think that this view of Christianity only plagued the ancients, let’s listen to a more up-to-date illustration. Michael Wigglesworth was a Puritan pastor (b. 1638-d.1705) who gave Puritans a bad name. Puritans, the Victorian era, etc., all seem to have received bad press nowadays—as though they were all up-tight, prudish, stick-in-the-mud, killjoys. This was certainly true of Wigglesworth, but hardly of the normal Puritan. Here’s just a few examples of his lifestyle:

“He . . . saw himself as guilty for lacking the Biblical attitude toward his parents [i.e., he had very little affection for them], and yet guilty for considering the creature at all. His blend of neoplatonism and Christianity ensured his guilt at all times.” (p. 39)

In other words, since the Bible teaches that children are to honor and respect their parents—and care for them in their old age—Wigglesworth condemned himself for failing to live up to this standard. On the other hand, as a neoplatonist, he felt that any consideration of fellow human beings was a sign of weakness, of giving in to his emotions, etc.: consequently, he felt guilty for even his dismal spark of feeling toward his parents.

“Like every neoplatonist, his world is egocentric; to rise above egocentricity to consider other people and to love them is to lose sight of God, in Wigglesworth’s eyes.” (p. 41) In a very real sense, neoplatonism has spawned narcissism and the ‘me-generation.’

“He enjoyed bad health; it was a way of denying the body; he enjoyed guilt, because it was a way of proving his dislike for the things of this world and his ‘sensitivity’ to their false claims. His ‘spiritual’ sensitivity rested, however, on a false premise which made him a moral monster” (italics added). (p.43)

Wigglesworth was a pretty fair poet in his day, though his poems were gloomy, reflecting his brand of ‘Christianity.’ Rushdoony tells us that:

“He also wrote, in ‘Vanity of Vanities,’ ‘what is Pleasure but the Devil’s bait?’ Beauty, friends, riches, all ‘draw men’s Souls into Perdition.’” (p. 48)

“Thus, as a good neoplatonist, he could write also a poem on ‘Death Expected and Welcomed.’ There was nothing in life that Wigglesworth enjoyed, or if he did, that he did not feel guilty about. He included also ‘A Farewell to the World,’ of which he said that it ‘is not my Treasure.’ Although he looked forward to the resurrection body, he had no good word for his present body, on which he heaped every kind of insult:

Farewell, vile Body, subject to decay,

Which art with lingering sickness worn away;

I have by thee much Pain and Smart endur’d;

Great Grief of Mind has thou to me procur’d;

Great Grief of Mind by being Impotent,

And to Christ’s Work an awkward Instrument.

Thou shalt not henceforth be a clog to me,

Nor shall my Soul a Burthen be to thee.

This is good neoplatonic dualism. It is alien to Biblical faith.” (p. 48)

This syncretistic blending of neoplatonism with Christianity plagues us to the present day. Two illustrations will suffice. (1) James Michener’s dislike of Christians is obvious in his book, Hawaii. The missionary (played by Max von Sidow in the movie) in the name of God promotes neoplatonism. It is quite unfortunate that, as much of a caricature as this portrait is, there is still an element of truth in it: neoplatonism has infected Christianity to the present day.

(2) Sex is often considered dirty by Christians. Several years ago when I worked in a machine shop I worked beside a man whose son was to be married soon. The young man and his bride-to-be were good Presbyterians and were going to get married in the church. The day before the wedding, this fellow lathe-operator told me that the wedding was off. I inquired why. He told me that the girl had just the night before announced that they were not going to have sex on the honeymoon. She intended to have sex only three times because she wanted to have only three children! Not only did she have a lot to learn about sex, but she had a lot to learn about the biblical view of sex!

All of us know of Christians who have tended toward a neoplatonic world-view. What I ask is that if you are a Christian, consider how it has infected your view of life. If you are not a Christian, listen further to what biblical Christianity is all about.

However, let’s put the shoe on the other foot. Neoplatonism has plagued western civilization in toto. It is, in fact, at the root of much drug abuse, the hippie movement, and radical feminism—as well as chauvinism. Listen again to Rushdoony:

On hippies (the book was written in 1973):

“This attitude is very much like that of the modern hippy, who despises the flesh and shows contempt for the body and its dress. The hippy, in his sexuality, expresses contempt for the body, either by treating sexual acts as of no account in casual promiscuity, or by a bored denial of sex. There is far more abstention from sex among hippies than is generally recognized. Either in abstention or in casual, unemotional promiscuity, it is a contempt of the flesh which is manifested. Dirty bodies and dirty clothing are other means of manifesting the same faith.” (p. 5)

On radical chauvinism (p. 11):

“The gospel of Sir Thomas More was his Utopia, wherein man’s mind imposed its idea on all of the world of matter. For More, wives were to be selected after being inspected naked; their minds were not important enough to count. So unimportant was matter or particularity, so little was it the world of the spirit, that wives were to be chosen without regard to the unity of mind and matter, naked on inspection like cattle.”

At least More was consistent—he practiced what he preached. When his daughters were old enough to be married, he herded them onto a platform, stripped them down before their courtiers, and married them off!

On inverted neoplatonism (p. 12):

“Inverted neoplatonism glorified nature and therefore women. The troubadors of medieval and Renaissance Europe downgraded love in marriage, because it belonged to the world of grace, which they identified as the platonic world of spirit. Adultery, on the other hand, belonged to the world of nature. The wife was thus a low creature, and the illicit lover a queen of love. As Valency noted, in writing of such adulterous love, ‘However illicit it might be from the point of view of religion and society, it had the sanction of nature; as matters stood it was grounded on firmer stuff than the marriage bond.’ ‘The sanction of nature,’ this is the key. Two worlds exist for neoplatonism, as for all dialecticism; they are alien to one another, so that, however much they exist as one, the world of matter and spirit, nature and grace, or nature and freedom, are somehow at odds with one another. If one is favored, the other must suffer. If the sanction of nature, illicit love, is exalted, the sanction of grace, lawful marriage, must be downgraded, because it is in principle unnatural for love and marriage, nature and grace, to be compatible.”

This inverted neoplatonism has reared its ugly head again in the 1960’s. One of the reasons it has done so, I’m afraid, is that the antithesis, neoplatonic morality, denied the goodness and joy of sex.

This inverted neoplatonism “is reflected in Demosthenes’ speech against Neaera, when he pointed out that ‘The hetaerae [prostitutes] are for our amusement, our slave women are for our daily personal service, and our wives are to bear us children and manage our household.’” (p. 25)

This produced something of a schizophrenic psychology, for one constantly saw a battle within himself between mind and body. “. . . some philosophers resolved the schizophrenic psychology in favor of the body, and hence concupiscence. Aristoxenus reflected this opinion:

Nature demands that we make lust the zenith of life. The greatest possible increase of sexual feeling should be every human being’s goal. To suppress the claims of the flesh is neither reason nor happiness; to do so is to be proved ignorant of the demands of human nature.

The Cynics in particular were intellectual champions of this position. “In every case, the warfare of body and mind was assumed; this conflict was in essence a metaphysical, not an ethical or moral conflict.” (p. 27)

“Modern man has not escaped the dilemma of Greek psychology. Some have chosen to ‘solve’ the problem by denying the body, as witness Christian Science, and others have denied the soul, as witness the Behaviorists. These ‘solutions’ are metaphysical, not moral. They leave only a fragmented man, as in the last days of the Greco-Roman world. The same is true of those who seek in the drug experience a flight from the world of the senses into the supposed timelessness and oneness of the world of the soul.” (p. 31)

Finally, neoplatonism has infected radical feminism:

“Much of what has been condemned as a product of Catholic and Protestant teaching has been the continuing influence of neoplatonism and best exemplified in its original form among Greeks and Romans.

“Neoplatonism was very powerful in the feminist movement of the 19th and 20th centuries. Now, however, the roles were reversed. Woman was seen as pure and spiritual, and man as coarse and material. Women, it was thus held, are more ‘spiritual’ and therefore superior beings. . . . Virginia Leblick in The New Era: Woman’s Era; or Transformation from Barbaric to Humane Civilization (1910) said that the lowest prostitute was better than the best of men.” (p. 65)

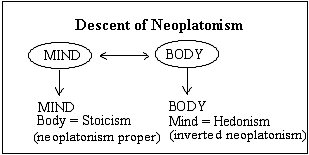

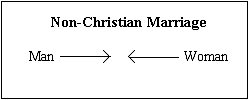

We can now illustrate the ‘descent of neoplatonism’ this way:

Summary

1. Neoplatonism sets up a false antithesis between body and soul. It forces one to make a choice (which one do you say ‘sick’em’ to?), when the biblical picture of the relationship of the material to the immaterial part of man is quite different. The apostle Paul says, for example, “Husbands, love your wives as your own body, for your wife is a member of your body. Now no man ever hated his own body, but he nourishes it and takes care of it” (Eph 5:28-29). If Paul had written this after the era of Michael Wigglesworth, he would have written, “No sane man ever hated his own body”!

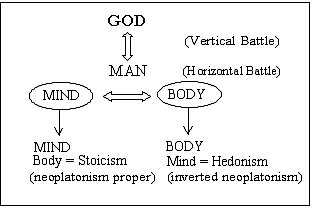

2. As Rushdoony points out, this false antithesis is due to the fact that people have rejected the real antithesis, the one between God and man:

“For Scripture, however, there is no such dialectical tension. The warfare is not between matter and spirit, nature and grace, or nature and freedom, but between sinful man and God. Man by his sin has declared war on God, and as a result is in a state of tension and warfare because of sin, not because of a dual nature. Man’s problem is moral and ethical, not metaphysical. Neoplatonism not only misrepresents the problem man faces, but, by making it metaphysical, makes it necessary to truncate or castrate man of a basic aspect of his being before he can be delivered.” (p. 12)

In other words, each man is in a battle, yes. But the battle is not within himself, but between himself and God. The Bible says that “God commended his own love toward us in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (Rom 5:8). That is, we are antagonistic toward God, but he has extended his love toward us. One of the curious things about neoplatonism is that it is universal. It is not found only in the west. In fact, the Greeks took some measure of satisfaction in noting that in India they could find ascetic parallels to their own philosophy. Rather than confirm the truth of neoplatonism, this confirms the direction in which all men travel when they reject the battle as having a vertical dimension. If God is left out of the picture, since all people sense a struggle, the only logical choice is a dialectical struggle within each person (after all, we all struggle with sin when no one else is around, so we can’t blame it on others all the time).

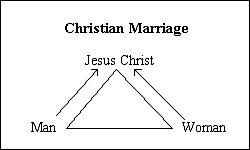

Now the illustration is complete:

Once a person rejects a world-view which sees man in conflict with God—a conflict only overcome through the payment of man’s sins by the death of Christ, the God-man—he virtually must adopt a one-dimensional view of the world. He no longer sees man as having the material and immaterial in partnership (the biblical picture), but instead sees them in conflict. By rejecting faith in God, he now must choose between mind and body, between the Spock syndrome and the Playboy philosophy. Most of us do not make a decisive choice, but instead swing the pendulum, creating fertile soil for schizophrenia.

II. A Biblical View of Sex

As lengthy as the first half of this lecture was, it provides a necessary backdrop for the remainder which, in reality, can be quite brief. All I want to do is touch on the four purposes of sex mentioned in the Bible.

A. Procreation