Which Son Obeyed his Father? The Textual Problem in Matthew 21:29-31

Related Media21:28 “What do you think? A man had two sons. He went to the first and said, ‘Son, go and work in the vineyard today.’ 21:29 The boy answered, ‘I will not.’ But later he had a change of heart and went. 21:30 The father went to the other son and said the same thing. This boy answered, ‘I will, sir,’ but did not go. 21:31 Which of the two did his father’s will?” They said, “The first.” Jesus said to them, “I tell you the truth, tax collectors and prostitutes will go ahead of you into the kingdom of God! 21:32 For John came to you in the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him. But the tax collectors and prostitutes believed him. Although you saw this, you did not later change your minds and believe him.” — NET Bible

Matthew 21:29-31 involves a rather complex textual problem. The variants cluster into three different groups: (1) The first son says “no” and later has a change of heart, and the second son says “yes” but does not go. The second son is called the one who does his father’s will! This reading is found in the Western manuscripts. But the reading is so hard as to be next to impossible. One can only suspect some tampering with the text (e.g., that the Pharisees would indeed give lip-service to obedience and would betray themselves in their very response) or extreme carelessness on the part of the scribe. (Either option, of course, is not improbable with this particular texttype, and with codex D in particular.) The other two major variants are more difficult to assess. Essentially, the responses are sensical (the son who does his father’s will is the one who changes his mind after saying “no”: (2) The first son says “no” and later has a change of heart, and the second son says “yes” but does does not go. But here, the first son is called the one who does his father’s will (unlike the Western reading). This is the reading found in א C* L W Δ Byz and many itala and Syriac witnesses. (3) The first son says “yes” but does not go, and the second son says “no” but later has a change of heart. This is the reading found in B Θ f13 700 and several versional witnesses.

Both of these latter two readings make good sense and have significantly better textual support than the first reading. The real question, then, is: Is the first son or the second the obedient one? If we were to argue simply from the parabolic logic, we would tend to see the second son as the obedient one (hence, the third reading). The first son would represent the Pharisees (or Jews) who claim to obey God, but do not (cf. Matt 23:3). This comports well with the parable of the prodigal son (in which the oldest son represents the unbelieving Jews). Further, the chronological sequence of the second son being obedient fits well with the real scene: Gentiles and tax collectors and prostitutes are not, collectively, God’s chosen people, but they do repent and come to God, while the Jewish leaders claimed to be obedient to God but did nothing. At the same time, the external evidence is weaker for this reading (though stronger than the first reading), not as widespread, and certainly doubtful because of how neatly it fits. One suspects scribal manipulation at this point. (One might even conjecture that the Western reading originated from some attempt to smooth things out, but the scribe got confused along the way and created a worse blunder, just as several Georgian witnesses seemed to do.) Thus, the second reading looks to be superior to the other two on both external and transcriptional grounds.

When one comes to the interpretation of the parable, it is of course possible that we ought not overinterpret. Jesus didn’t always give predictable responses. Chronological sequencing was not necessarily a part of the parabolic package. For example, in the eschatological parable of the wheat and darnel (Matt 13:24-30), it is the darnel that is gathered first and thrown into the furnace; but in the eschatological parable of the sheep and goats (Matt 25:31-46), the sheep go into the kingdom first, then the goats receive their punishment (vv. 34, 46). We must be careful not to make parables walk on all fours; that is, not every point in the parable has interpretive correspondence.

However, in this instance, the sequencing seems to be intentional—and many scribes, though trying to improve on the logic of the presentation, missed the rhetorical power of Jesus’ message. The Lord seems to have painted a picture in which the Pharisees saw themselves as the first son. They would have regarded themselves as in a place of privilege, the first ones chosen by God, and those who actually obeyed the Father’s will. (One is reminded of the ancient rabbinic prayer: “I thank you, Lord, that you did not make me a woman or a Gentile”!) Then came the O’Henry twist: The Pharisees are not the first son, but the second. They are not the ones who have obeyed their heavenly Father, but the tax collectors and prostitutes are! In some respects, this chronological reversal is reminiscent of Nathan’s approach to King David when he pointed out his sin with Bathsheba (2 Sam 12:1-7). Both Nathan and Jesus ‘set up’ the hearers to elicit a certain response (that of indignation at the disobedient one in the story), only to show that those very hearers were not on the side of righteousness.

Thus, when one looks at the internal coherence of the story, it seems evident that the Western reading flattens out the mystery and presents the Pharisees as not only unrighteous but blithering idiots. But such a lack of subtlety was probably not a part of the story or the historical situation. And the third reading improves the text—at first glance—but in reality seems to unravel the rich tapestry that is being woven by the Master Teacher himself.

Related Topics: Fathers, Men's Articles, Textual Criticism

The Five Big Events of the Millennium

Related MediaThe Human Events issue of 31 December 1999 published the opinion of ten leaders as to the five greatest events of the last millennium. The leaders were professors, authors, lawyers, politicians: Phyllis Schafly, William Rusher, Terry Jeffrey (editor of Human Events), M. Stanton Evans, Charles Rice (Notre Dame Law Professor), Edwin Feulner (Heritage Foundation), Tom Palmer (Cato Institute), Herbert London (president of the Hudson Institute), Allan Carlson (Howard Center), and Ann Coulter (lawyer).

I wish to offer a very brief commentary on what was selected by these leaders. I have two simple points to make. (1) As I look at the biggies that these ten leaders chose, I am especially intrigued by the values that these individuals have. If they consider personal and political freedoms as high on the list, their big five reflect this (e.g., Magna Carta, Declaration of Independence, American Revolution). If they value technology and science, then Galileo, the transistor, and DNA get the nod. If intellectual pursuits and new horizons of exploration are important, then Columbus’ landing in America, Gutenberg’s printing press, Descartes’ cogito ergo sum, and several important books (e.g., Newton’s, Aquinas’, etc.) often get mentioned. If how one relates to God is important—especially how a community relates to God—then the Pope’s deeds and Aquinas are listed. What I found very curious, however, was what was missing from all of these lists. This leads me to my next point.

(2) Two items spoke volumes by their omission: The Turkish invasion of Byzantium in May of 1453 and Martin Luther’s nailing the 95 theses on the door of the Wittenberg church. Ironically, far more people are aware of Luther’s act than that of the Turks, yet the invasion was real while Luther's deed was, as far as we know, a bit apocryphal. That is, apparently Luther never nailed those theses to the door (an act which is largely misunderstood anyway; it signified at that time a challenge to a public debate, not disrespect for the church). Yes, Luther wrote the theses, and yes, they were distributed throughout Europe within weeks (about 100,000 copies were made very soon thanks to Gutenberg’s press), signalling the start of the Reformation. But that Luther actually physically nailed the theses to the church door is, as I understand it, a myth. But his writing of and the distribution of the 95 theses must surely be one of the five most significant events of the millennium. Western Europe (and all the continents that were discovered by western Europeans) was forever changed because of this event. The authority structure of people’s lives changed from tradition to revelation and reason. As for the Turkish invasion of Byzantium: its importance is in the fact that when it took place the Greek scholars fled with their manuscripts into the rest of Europe. And soon afterward, Europe awakened to the treasures of the Greek world: the Renaissance was born in the south and the Reformation in the north as a result. That it happened one to three years before Gutenberg’s press (we’re not really sure of the exact year that he invented moveable type) was a great ‘coincidence.’

So what are the big five I would choose? In chronological order: (1) The Turkish invasion of Byzantium (1453), (2) Gutenberg’s printing press (c. 1454-56), (3) Columbus’ discovery of America (1492), (4) the publication of Luther’s 95 theses (1517), and (5) I can’t decide! But that these first four all took place within a period of 75 years—and not within the 20th century—ought to humble us about how great this past century has been. It truly has been a marvel on a technological level. But what about an ethical level? Have we made great strides in ethics, or more particularly, in the Christian faith? As Dr. John Hannah, historical theologian at Dallas Seminary, predicted nearly 25 years ago: “All generations of Christians are marked by one theological point or another. The present generation will undoubtedly be marked by hamartiology [the doctrine of sin].” He said this somewhat tongue-in-cheek: We are not marked by the doctrine of sin, but by its practice. That we have honed to an art form.

Related Topics: Cultural Issues

New Testament Eschatology in the Light of Progressive Revelation

Related MediaThe following rough essay is intended to be something to think about; it is neither a polished piece nor altogether finalized in my own thinking. I welcome interaction and criticisms from all quarters.

Preface

Certain assumptions made by premillennialists and amillennialists about eschatology in the NT may well be wrong-headed. Specifically, both sides tend to flatten out eschatology so that the whole can be seen in any part. Premillennialists tend to see a time-bound earthly kingdom in the OT where none exists; amillennialists tend to interpret the Apocalypse only in the light of previous revelation, rather than allowing that book to govern and guide all earlier interpretation.

Thesis One: Only as revelation unfolds, do we see clearly the distinction between certain eschatological events--such as between the earthly kingdom and the eternal state. (Our main contention is that a time-fixed earthly kingdom is not taught until Rev 20.) We already have such a pattern in Isa 61:1-2 (cf. Jesus’ use of it in Luke 4:18-19, in which he omits the last line of text which speaks of God’s vengeance, because it was not yet fulfilled).

Curiously, most students of the Bible assume progress between the testaments, but deny it within the NT. To be sure, the time frame is much shorter. But there is ample evidence of progressive revelation within the NT about several themes--that is, certain themes are not developed/recognized until after some time (including the deity of Christ and of the Spirit, the idea that our souls go immediately to heaven, the fact of the rapture, etc.).

Thesis Two: Prophetic telescoping is due to prophetic ignorance. That is to say, when there are major gaps in a prophet’s eschatological scheme, this seems to be due to him not knowing of what goes in the gap.

Demonstration

The idea of a time-fixed earthly kingdom is not taught until Rev 20. Reading the Bible chronologically reveals that the millennial kingdom is not clearly distinguished from the eternal state until the last book of the Bible. Amillennialists have argued this for some time; and their point is that therefore Rev 20 needs to be interpreted in light of earlier prophecies. But surely they would not do this with the first and second comings of Christ: that is, even though the two comings are not clearly distinguished in the OT, amillennialists recognize that the Bible affirms a second coming. My point is that progressive revelation shows that just as the two mountain ranges of Christ’s two comings are virtually indistinguishable in the OT, so also the two future stages of the kingdom do not get distinguished until AD 96.

Specifically, the OT texts do not make a distinction between the earthly kingdom and the eternal state (cf. the intermingling of the two in Isa 65:17-25). Only with exegetical gymnastics can one find this distinction between the earthly kingdom and eternity in the Olivet Discourse.1 First Corinthians 15:21-28 is often used as a prooftext for the millennial kingdom, but without Rev 20, no one would see it.2 Hindsight is 20/20. Further, 2 Pet 3:10 seems to view the Lord’s return as ushering in eternity (“But the day of the Lord will come like a thief; when it comes, the heavens will disappear with a horrific noise, and the heavenly bodies will melt away in a blaze, and the earth and every deed done on it will be laid bare.”3) Likewise, 2 Thess 1:9-10 seems to ‘telescope’ the eschaton (in that there is no gap between the Lord’s return and the eternal destruction of the wicked).

In the treatment of such passages, I believe the amillennialists have had a superior exegesis. Premillennialists often have such a flat view of revelation that they see things that are impossible historically. For example, is it really plausible to say, as Leon Wood does in his commentary on Daniel, that we should read Dan 2:44 as “the God of heaven will set up a kingdom which will not be destroyed for an age”?4 The Aramaic term ‘lma’ [lamá] (equivalent to the Hebrew ‘olam) can, of course, in some contexts mean ‘age’ rather than ‘eternity.’ But to argue that here is pure dogma. Wood says, “According to Revelation 20:3, the millennial kingdom lasts 1000 years, the duration of time intended here.”5 There is not a shred of evidence in all of Daniel to suggest that he intended 1000 years. Wood simply argues this from the vantage point of Rev 20.

What am I saying? I am simply arguing that we need to read the Bible in light of the progress of revelation--not only between the testaments but also within each testament. Even within the NT there is progressive understanding. We (i.e., both pretribulationists and posttribulationists) tend to impose a systematic framework on the text, rather than adhering to a biblical approach to exegesis in this instance. Although we would agree that scripture does not disagree with itself, we would be quite wrong to assume that the finality of revelation was known in its details before it was ever recorded.

If we were to chart out the progress of revelation according to the time of the prediction, we would see the following:

Old Testament prophecies taken as a whole: mixture of earthly kingdom and eternal state (cf. Isa 65; Dan 2, 7; Jer 31:31-40)6; resurrection of the righteous and wicked occurs simultaneously at the end of the tribulation (Dan 12:1-2).

Olivet Discourse (AD 33): eternal kingdom on earth = eternal life; perhaps other ‘confusions’ such as: tribulation/Jewish war as prelude to Lord’s return; judgment of the nations (Matt 25) seems to encompass two judgments: Great White Throne Judgment (at end of the millennium) & a preliminary judgment to determine who goes into the millennium (cf. Dan 12:1-2).7 When one reads of this judgment in Matt 25:34-46, only unpacking it later in light of Rev 20, it seems probable that two distinct judgments really are in view.

1 Thess 4:13--5:11: Resurrection of Christian believers seems to take place pretribulationally; while resurrection of OT saints is still posttribulational, along with the resurrection of the wicked dead.

2 Thess 1:9-10 (AD 49): Immediately after the Lord returns, eternal judgment is meted out on the ungodly. There is no hellish holding tank; the Great White Throne Judgment (though not called by that name) takes place at the Lord’s advent.

2 Pet 3:1-13: new heaven and new earth come when the Lord returns. The eternal state is thus earthly and heavenly.

Rev 20:1-6: earthly kingdom is 1000 years and is clearly distinguished from the eternal state which is to follow; resurrection of the wicked dead occurs after the millennial kingdom.

By comparing these various passages, one can see that, as time goes on, earlier melting pot prophecies get unpacked and sorted out.

Implications

It is not valid to argue against premillennialism simply because the distinction between the eternal state and the earthly temporary kingdom is not made until Rev 20. Earlier revelation must yield to later revelation in this matter, just as it does in other theological areas (such as the Trinity). What gives us a right to argue for a thousand-year kingdom? The 1000 years are mentioned both in the prophecy and its interpretation. When this is the case in Revelation, we must seek no other interpretation.

If the first coming--second coming matrix is at all paradigmatic for the remainder of prophecy, then we all must be less than dogmatic about both date-fixing and claims of thorough comprehension about certain eschatological events. Many prophecies that look like single events may well be multiple events. How can we be sure? Only as we get closer to the mountain peaks off in the distance can we distinguish them. In the case of Jesus’ first coming, it was not even distinguished by his disciples until after he died and rose again.

Surely there are other areas of biblical theology where we have imported our finalized conclusions without giving the historical situation of the text in question its due. Much profit can be gained from looking at scripture through the historical lens as opposed to the systematic lens of centuries of formulation. These two must be complementary, though, not contradictory.

1Note that Matt 25:34 (“inherit the kingdom”) and 25:46 (“the righteous [will enter] into eternal life”) are, most naturally, speaking about the same event. Yet, if we try to distinguish the millennium from the eternal state in this discourse we have something of a contradiction. Further, it is equally difficult to distinguish the tribulation before the Lord’s return from the Jewish War. I strongly suspect that Jesus himself was unaware of such distinctions (cf. Matt 24:36).

2Cf., e.g., Fee’s NICNT commentary, loc. cit. The most we can get out of 1 Cor 15:21-28 is that there may be some time for Christ to do his ‘clean-up operation’--that is, to bring everything, including death, under submission to his sovereignty. But to read into this text a one thousand year period is unwarranted. Indeed, it seems equally plausible to extract from this text the notion that Christ is now reigning and is bringing everything under his submission (v 25). “Then comes the end” (v 24), in this scenario, would support a postmillennial/amillennial position. Suffice it to say that the millennium is anything but clear in this text.

3 NET Bible translation.

4L. Wood, A Commentary on Daniel, 71.

5Ibid., 73.

6 There are other potential confusions in the OT such as in Ezek 38-39 where the prophecy against Gog and Magog is usually taken to refer to the great battle at the end of the millennial kingdom. But it could also refer, as a sort of pre-fulfillment, to the great battles during the last half of the Tribulation.

7 Premillennialists tend to see this judgment as at the beginning of the millennial kingdom and the Great White Throne Judgment as at the end.

Related Topics: Eschatology (Things to Come)

The Textual Problem Of "οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός" In Matthew 24:36

Related MediaA curious textual problem occurs in Matt 24:36. The NA27/UBS 4 text reads Περὶ δὲ τῆς ἡμέρας ἐκείνης καὶ ὥρας οὐδεὶς οἶδεν, οὐδὲ οἱ ἄγγελοι τῶν οὐρανῶν οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός, εἰ μὴ ὁ πατὴρ μόνος1 (But concerning that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, nor the Son, except the Father alone). Many manuscripts (א1 L W f1 33 Ï), however, omit οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός. Perhaps the omission was a theologically motivated change in order to preserve Jesus’ omniscience. However, why would the scribes omit the phrase in Matt 24:36 and not in Mark 13:32? Only Codex X, the Latin Vulgate, and a few other Greek manuscripts omit it. Is it possible that certain scribes could have harmonized the text of Matt 24:36 to that of Mark 13:32? Several factors need to be considered in this problem besides external evidence and the theological motivations of certain scribes. First, could the anti-Arian discussions among the church fathers of the fourth and fifth centuries CE have affected the transmission of Matt 24:36? Second, do the scribes of א, B, D tend to harmonize toward Matthew or toward Mark? Third, how would scribes have interpreted εἰ μὴ ὁ πατήρ in Mark 13:32? Could the ancient scribes interpreted εἰ μὴ ὁ πατήρ in Mark 13:32 as simply preeminently true as opposed to exclusively true? If so, they could omit the phrase in Matthew, but not necessarily in Mark. These three factors need to be taken into consideration in order to evaluate adequately the internal evidence of this textual problem.

External Evidence

Before we take a look at the internal arguments, a brief examination of external evidence is in order. Favoring the reading of οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός is א and B the two fourth century primary uncials of the Alexandrian textttype. The Western text is represented by the fifth century uncial D as well as several manuscripts of the itala, some of which are as early as the fourth century. The Caeserean text is represented by minuscules of f13 and 28, but no manuscript is earlier than the eleventh century. The Byzantine text is represented by Θ from the ninth century and 1505 from the eleventh century. In addition to the Greek manuscripts and the itala, there is versional evidence in the Latin Vulgate, Ethiopic, Armenian, Georgian versions. Patristic evidence includes Irenaeus (Latin),2 Origen (Latin),3 Epiphanius,4 Dydimus,5 Cyril of Alexandria,6 Chrysostom,7 Hilary,8 Ambrose,9 Augustine,10 and Latin manuscripts according to Jerome.11 Geographic distribution, therefore, includes all four texttypes, but only in the Alexandrian and Western texttypes is the distribution definitive before the fifth century.12 In terms of genealogical solidarity, the witness of א and B suggests that the reading goes back to an early second century archetype. The Western text also points to a second century archetype with the alignment of D, the early itala, and the witness of Irenaeus. Thus, there is good and early manuscript support for the inclusion οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός.

The support for the omission is not as impressive but it does have some merit. The evidence is mainly Byzantine including the uncials N W Σ of the fifth and sixth centuries. Codex L and 33 represent the Alexandrian texttype, while f1 565 and 579 represent the Caeserean text. In addition to this, the first corrector of א also represents the omission, a point that should not be overlooked since Sinaiticus may very well have been corrected before it left the scriptorum. While the Greek manuscripts are not that impressive, the omission has good versional support in Coptic, Syriac, and the Latin Vulgate. There is also patristic support in Origen, Athanasius,13 Dydimus,14 Jerome,15 Greek manuscripts according to Jerome16 and Ambrose,17 Phoebadius, Gregory of Nyssa,18 and Basil.19 The omission also has geographic distribution in all four regions, and it is early in the Alexandrian, Western and Byzantine regions.20 Genealogical solidarity can only be found in the Byzantine texttype, which has a fourth century archetype.

While the inclusion of οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός definitely has the edge in terms of date and character and genealogical solidarity, geographic distribution is practically a tie, and perhaps leans in the direction of the omission. It is also to be noted that there is no representation from the papyri for either reading, so the external evidence is not as one-sided as it is often made out to be. External evidence should be probably be rated a B+ according to the UBS rating scale in light of all the factors.

Internal Evidence

The internal evidence is much more difficult to decide. Before we address the main disputes it would be helpful to examine transcriptural probability to see if the possibility of an accidental error is possible.

Transcriptural Probability

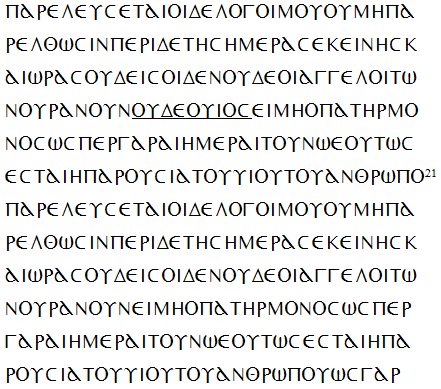

The following is a layout of how the variants would look in uncial script.

It is possible that a scribe simply skipped over οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός because of the first οὐδέ phrase. This, however, would not explain the deliberate deletion by the first corrector of א.22 Whether the first corrector was conforming the text to the exemplar or to other manuscripts that he knew to omit the phrase is a matter of speculation. While an accidental error is possible, it may not be the best explanation.

Two divergent explanations have been given that argue for an intentional alteration. Note Metzger’s comments.

The words “neither the Son” are lacking in the majority of the witnesses of Matthew, including the later Byzantine text. On the other hand, the best representatives of the Alexandrian, the Western, and the Caesarean types of text contain the phrase. The omission of the words because of the doctrinal difficulty they present is more probable than their addition by assimilation to Mk 13.32. Furthermore, the presence of μόνος and the cast of the sentence as a whole (οὐδὲ…οὐδὲ…belong together as a parenthesis, for εἰ μὴ ὁ πατὴρ μόνος goes with οὐδεὶς οἶδεν) suggest the originality of the phrase.

However, the textual note on Matt 24:36 in the NET Bible argues differently:

Early Alexandrian and Western witnesses add οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός (oude Jo Juios, “nor the son”) here. Although the shorter reading is suspect in that it seems to soften the prophetic ignorance of Jesus, the final phrase (“except the Father alone”) already implies this. Further, the parallel in Mark 13:32 has οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός, with almost no witnesses omitting the expression. Hence, it is doubtful that the omission of “neither the Son” is due to the scribes. In keeping with Matthew’s general softening of Mark’s harsh statements throughout his Gospel, it is more likely that the omission of “neither the Son” is part of the original text of Matthew, being an intentional change on the part of the author. Further, this shorter reading is supported by the first corrector of א as well as the following: E F G H K L M N S U V W Γ Δ Π Ë1 33 Byz vg syr cop, along with several mss with which Jerome was acquainted. Admittedly, the external evidence is not as impressive for the shorter reading, but it best explains the rise of the other reading (in particular, how does one account for virtually no mss excising οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός at Mark 13:32 if such an omission here is due to scribal alteration? Although scribes were hardly consistent, for such a theologically significant issue at least some consistency would be expected on the part of a few scribes).23

The arguments appear to be somewhat balanced. On the one hand, Metzger and the majority of commentators24 argue for the inclusion on the basis of the harder reading, the tendency of scribes to remove theological difficulties,25 and grammar.26 On the other hand, Allen, Plummer, and Wallace argue for the omission on the basis of the shorter reading, scribal harmonization to Mark 13:32, and Matthean style of softening Mark’s harsher statements. In order to evaluate the weight of these arguments, three things need to be considered: 1) scribal tendencies in harmonizing the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, 2) the use of Matt 24:36 and Mark 13:32 in the Arian controversies of fourth century CE, and 3) the range of meaning of εἰ μὴ ὁ πατήρ.

Scribal Tendencies in Harmonizations

When we looks at the textual variants involving scribal harmonizations between Matthew and Mark, we note that it was more common for scribes to harmonize Mark to Matthew. In the table in Appendix II, we have 61 of the most significant instances involving harmonization.27 Of the 61, only eighteen involve harmonizations from Matthew to Mark or about 30%. Therefore, about 70% involve harmonizations from Mark to Matthew. What is also significant is that scribes harmonized Mark 13:32 to Matt 24:36 in two places.28 But what are the scribal tendencies of the major manuscripts, א, B, and D, in harmonizing the Gospels of Matthew and Mark? The scribe of Codex Sinaiticus harmonizes Matthew to Mark about six times, while he harmonizes Mark to Matthew nineteen times. The scribe of Codex Vaticanus harmonizes Matthew to Mark only twice, but conforms Mark to Matthew twelve times. The scribe of Codex Bezae conforms Matthew to Mark seven times, while Mark is harmonized to Matthew nineteen times. Both א and D change Mark’s ἤ τῆς to καί in Mark 13:32. Clearly the tendency among these scribes is to conform Mark to Matthew, especially the scribe of Vaticanus.

However, this does not settle the issue. Since Matthew has a tendency to soften Mark’s harsher statements and to strike out statements that imply Jesus’ ignorance, one needs to look at whether texts that involve this type of softening are harmonized to Mark. Texts in Mark, but not in Matthew where Jesus expresses ignorance or inability include Mark 1:45; 5:9, 30; 6:5, 38, 48; 7:24; 8:12, 23; 9:16, 21, 33; 11:13; 14:14. However, none of these statements in Mark appear in the manuscripts of Matthew surveyed. Neither are the statements in manuscripts of Mark omitted to conform to Matthew. In fact, the only place where Matthew’s “softening” language is altered by the scribes is in Matt 19:17 where τί με ἐρωτᾷς περὶ τοῦ ἀγαθοῦ is replaced with τί με λέγεις ἀγαθόν in C, E, F, G, H, W, Δ, Σ, f13, Ï. But this is a much different type of change than the addition of οὐδες ὁ υἱός in Matt 24:36. Therefore, even though Matthew has a tendency to soften Mark’s harsher language, the ancient scribes very rarely assimilated Matthew to the harsher language, and even avoided conforming Mark to Matthew’s softer language.

Matt 24:36 and Mark 13:32 in the Arian Controversies

Matthew 24:36 and Mark 13:32 was a storm-center amidst the church fathers in the Arian controversies of fourth century AD. Both sides utilized these texts in their arguments and at several points the inclusion or omission of οὐδες ὁ υἱός in Matt 24:36 becomes the center of attention. The fathers that argue about these texts the most are Athanasius, Gregory Nazianzen, Basil, Ambrose, Hilary, and Augustine. Athanasius basically argued that Jesus only knew according to his divine nature, but did not know according to his human nature.29 He argues that Jesus really did know the time of his coming, but portrayed himself to the disciples as ignorant in order to teach them not to speculate. Athanasius is also reported to claim at the council of Nicea that οὐδες ὁ υἱός was not in Matthew, but only in Mark. He then tries to demonstrate that Mark 13:32 must be understood differently than Matt 24:36 by appealing to Jesus’ oneness with the Father (John 10:30) and asserts that if the Son is one with the Father, he must also be one in knowledge.30 Even though this text is considered spurious, it probably reflects Athanasius’ sentiments, if not his words. Similarly, Gregory Nazianzen, in answering the tenth objection of the Eunomians concerning the Son’s ignorance of the last day, argued that the Son knew as God and did not know as man. He also argues that if the Father knows, then the Son also knows in terms of the First Nature.31 Basil compares Matt 24:36 and Mark 13:32 and understands the texts differently. Since Basil’s text of Matthew omits οὐδες ὁ υἱός, and Mark omits μόνος, he reasoned that Mark meant something different from Matthew. He argued that the Son’s knowledge proceeds from the Father. He asserted that Matthew’s μόνος had reference only to the angels and that the Son was not included in the matter of ignorance.32 Chrysostom argues that the Son is not ignorant of anything, but said this only so the disciples would not pursue the question further.33

Ambrose interacts with the Arians’ citation of Matthew 24:36 by claiming that the ancient manuscripts do not contain οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός but the Arians added it in order to corrupt and falsify the passage. Ambrose completely ignores the fact that the words are in Mark 13:32 or believes that either the words are missing in Mark also or that Mark must be interpreted differently.34 Hilary goes to great lengths to prove that Christ was omniscient. He argued that Christ was simply accommodating himself to the language of man because he was also man. Therefore, in human terms, he does not know that which is not yet time to declare or that which is not worthy of his recognition.35 Finally, Augustine claimed that the Son’s ignorance is in reference to making other’s ignorant. In other words, since it was not yet time for Christ to reveal the time of his coming to the disciples, he thus professed “ignorance.”36 In a sense his argument is very similar to Hilary’s.

The Interpretation of εἰ μὴ ὁ πατήρ in Mark 13:32

It is apparent from the preceding discussion that several of the church fathers were interpreting εἰ μὴ ὁ πατήρ in Mark 13:32 differently from that of Matt 24:36. Matthew’s μόνος makes the interpretation of the εἰ μή clause as an absolute exception certain. But is it necessary to view it this way in Mark? While it is often observed in the grammars that the use of εἰ μή with the verb omitted means “except” or “but” and is considered a substitute for ἀλλά,37 this is not always the case. Εἰ μή conditionals are actually very ambiguous; therefore, two contextual assessments need to be made which will determine whether or not a translation of “except” or “but” for εἰ μή is adequate. First, the context must suggest that the author/speaker believes that the unnegated protasis is true. Second, the context must suggest that the author/speaker considers the unnegated protasis to be exclusively true in some way rather than simply preeminently true.38 If either of these things are not true, then the meaning of the author will be changed if such sentences are translated with “except” or “but.”

In preeminently true conditionals, the protasis does not name something that is an exception or exclusively true. Instead, it names something that is preeminently true. With these kinds of conditionals, a dynamic equivalent or periphrastic translation is often necessary to bring out the preeminently true sense of the conditionals. There are 27 instances of this type of conditional in the NT, but two examples will suffice.39

First, in Matt 11:27, after reproaching the cities that did not repent because of his signs and ministry, Jesus turns and thanks his Father for his wisdom concerning those he did draw to Jesus. He then invites the disciples and those around him to come to him for rest. The basis for his invitation is the mutual relationship between the Father and the Son, and the privilege of the Son to reveal the Father to others.40 Most English translations give the appearance that the Son is exclusively known by the Father. But certainly many people knew Jesus apart from the Father. While it is possible that ἐπιγινώσκει could refer to some “special” knowledge of the Son,41 that meaning would be difficult to prove here, especially since the parallel in Luke 10:22 uses γινώσκει. Romans 1:21 asserts that all men have some knowledge of God, and even here, some people can know the Father. It seems strange to claim that some people can have knowledge of the Father while only the Father can know the Son. This would make knowledge of the Son more obscure than knowledge of the Father.42 Since the conditional statements do not demand that the unnegated protases are exclusively true, it seems better to see them as preeminently true. The Father knows the Son preeminently, or better than anyone else, and the Son knows the Father preeminently, or better than anyone. Therefore, the Father is preeminently knowledgeable about the Son, and the preeminent source for knowledge of the Father is the Son.43

Second, in Matt 13:57 (Mark 6:4), when Jesus returns to Nazareth and teaches in the synagogue there, he is met with opposition. Jesus replies to their opposition with this statement: “A prophet is not without honor, if not in his hometown, and in his household” (οὐκ ἔστιν προφήτης ἄτιμος εἰ μὴ ἐν τῇ πατρίδι καὶ ἐν τῇ οἰκίᾳ αὐτοῦ). This statement raises a couple of questions. First, does Jesus believe that the unnegated protasis is true (a prophet is without honor in his own hometown)? While he believes that it is true in his case and in the case of many prophets, it does not necessarily mean that it is true in every case. More than likely this is a proverbial statement, something that is usually true, but not necessarily true.44 So, Jesus is saying that it is usually true that a prophet is without honor in his hometown, not that a prophet cannot have honor in his hometown. Second, is the unnegated protasis exclusively true? In other words, the prophet must have honor everywhere else, except in his hometown. This is certainly false. Many prophets were not honored in most of the places they went. Jesus himself was rejected in many places outside his hometown. Therefore, this statement is saying that the prophet’s hometown is the preeminent place in which he is without honor. It is the first place a prophet can be expected to be rejected.45

This preeminent sense seems to be the way the church fathers are understanding Mark 13:32. This is especially clear in Basil. In a letter to Amphilochius,46 He specifically addresses the issue of Christ’s ignorance of the day and hour of the end and takes issue with the Anomoeans. His first argument is that οὐδείς is not necessarily inclusive of everyone in Scripture. His first example of this is Mark 10:18: “No one is good if not one, God” (οὐδεὶς ἀγαθὸς εἰ μὴ εἷς ὁ θεός). He argues that the Son is excluded in reference to these words and that it should be understood that this is a reference to the Father being the “first good” (τὸ πρῶτον ἀγαθόν), with the word “first” being understood (τὸ οὐδεὶς συνυπακουομένου τοῦ πρῶτος). He argues the same way with Matt 11:27, as we did above, only that he asserts that the Spirit is not charged with ignorance, but that Christ acknowledges that the knowledge of his own nature exists with the Father first. The Father has the first knowledge of the things present and future, and the statement in Matt 11:27 was indicating to all the First Cause. Thus, he clearly shows that the εἰ μή clauses were to be understood in a preeminent sense.

Basil next applies this understanding to Mark 13:32 in comparison with Matt 24:36. As noted above, he makes much of Matthew’s omission of οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός and the absence of μόνος in Mark. He also capitalizes on John 10:15 (even as the Father knows Me, I also know the Father). He then recasts Mark 13:32 into a second class condition47 and argues that no one would know the day and the hour, not even the Son would have known, if the Father had not known. Thus, he argues that the Son derives all knowledge from the Father and the Father is the cause of his knowledge in everything.

Finally, Basil admits to Amphilochius at the beginning of the letter that his understanding of this issue and these passages was that which he learned from the fathers since his boyhood and that the issue had been examined by many. This strongly suggests that this understanding of the Mark 13:32 has been in the church for some time. Therefore, this understanding is probably also shared by Athanasius, Gregory Nazianzen, Ambrose, and the other church fathers who entered into the Arian controversy. It seems most probable then that ancient scribes familiar with the preeminent understanding of εἰ μή clauses, desired to adopt that interpretation of Mark 13:32. However, knowing that μόνος in Matt 24:36 made this understanding impossible, they dropped οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός to harmonize it with their interpretation of Mark.48

Conclusion on Internal Evidence

It appears that internal evidence leans toward the inclusion of οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός in Matt 24:36. First, scribes tended to conform Mark toward Matthew far more than Matthew to Mark. Second, scribes almost never conform Matthew’s softer language to Mark’s harsher statements, nor do they alter Mark to Matthew’s softer language. Third, in two places Mark 13:32 was conformed to Matt 24:36. Fourth, Matt 24:36 and Mark 13:32 were a hotbed of debate in the Arian controversies of the fourth century, and the omission οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός in Matthew was often used against the Arians. The fathers, then, understood Mark 13:32 differently from Matt 24:36. Finally, εἰ μή clauses can have a preeminent sense if the context so determines. It is clear that Basil understood Mark 13:32 in this way, and this is the most probable explanation for the understanding of this text by the other church fathers. The inclusion of οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός is the harder reading and appears to better explain the rise of the omission. Internal evidence should probably rated a C.

Conclusion

External evidence clearly favors the inclusion of οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός in Matt 24:36. The reading is represented by the best and earliest manuscripts in א and B. It has good geographical distribution among the versions and the Fathers, and it has good genealogical solidarity among the Alexandrian and Western texttypes. Internal evidence is a bit more difficult but the inclusion of the phrase is the harder reading. It also seems to be the better explanation for the rise of the omission because the scribes would be motivated by christological reasons to omit the phrase. There is evidence of this motivation in the church fathers in that they seem to interpret Mark 13:32 in a preeminent, rather than an exclusive sense. Also scribal harmonizations tend toward Matthew, and rarely is Matthew conformed to Mark’s harsher language. Overall, the decision concerning this conclusion should probably rated a C+.

Finally, it is more likely that Mark did intend 13:32 to be understood in an exclusive sense, and it is this sense that Matthew makes clear with the addition of μόνος. The attitude of the church fathers is understandable. They were still in the process of doctrinal development with respect to the Trinity and the hypostatic union. They wanted to defend Christ’s deity and still affirm his humanity. The continuing controversies with the Arians and their allies forced them to wrestle with the theology of these texts. And perhaps they were closer to the truth than they are currently given credit for. There may be some sense that Christ knew what the Father had planned for the final outcome. But Jesus had not yet completed his mission on earth. The time of his coming in glory is contingent upon the completion of his earthly mission. Until he experienced his death and resurrection, he could not really know the time of his return. He even had questions concerning the necessity of his death (cf. Matt 26:39-42; Mark 14:36; Luke 22:42). But upon his resurrection and ascension, both the fact and time of his coming became a certainty for Him.

Appendix I

Chart Of External Evidence

|

Reading #1 |

οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός |

|||||||

|

|

BYZANTINE |

CAESAREAN |

ALEXANDRIAN |

WESTERN |

OTHER |

|||

|

Papyri |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Uncials |

Θ- IX |

|

*, - IV, B- IV |

D- V |

2vid |

|||

|

Minuscules |

1505- 1084 |

f13 XI-XV, 28- XI |

|

|

|

|||

|

Lectionaries |

|

|

|

|

l 5471⁄2- XIII |

|||

|

Versions |

eth- VI

|

arm- V geo- V |

|

ita, aur, b, c, d, (e), f, ff1, ff2, h, q, r1 - IV-VII vgmss-IV-V |

|

|||

|

Church Fathers |

Diatesarm-IV Chrys- IV Hesych- V |

|

Orlat- III Epiph- IV Dydimus- IV Cyril- V |

Irenlat- II Hilary- IV Ambrose- IV Latin MSSacc. to Jerome- IV Aug- IV-V Varimad- V |

|

|||

|

Reading #2 |

omit |

|||||||

|

|

BYZANTINE |

CAESAREAN |

ALEXANDRIAN |

WESTERN |

OTHER |

|||

|

Papyri |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Uncials |

E- VIII, F- IX G- IX, H- IX K- IX, M- IX, N- VI, S- 949 U- IX, V- IX, W- V, Γ-X Δ- IX, P-IX, Σ- VI |

|

L- VIII |

|

1 |

|||

|

Minuscules |

180- XII 205-XV 597- XIII 700- XI 1006- XI 1010- XII 1292- XIII 1424- IX-X Byz- IX-XV |

f1- XII-XIV 565-IX 579- XIII |

33- IX 892- IX

|

|

157- 1122 1071- XII 1241- XII 1243- XI 1342-XIII-XIV

|

|||

|

Lectionaries |

Lect- IX-XVI |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Versions |

syrp, h- V-VI |

geoA- VIII-IX |

copsa, meg, bo- III |

itg1, l- VIII-IX vg- IV-V syrs- II-III |

|

|||

|

Church Fathers |

Basil- IV Greg Nys- IV |

|

Origen- III Athan- IV Didymusdub- IV Greek MSSacc. to Jerome- IV |

Greek MSSacc. to Ambrose- IV Jerome- IV-V Phoebad- IV Pailinus-Nola- V |

|

|||

Appendix II

Table Of Matthew/Mark Scribal Harmonizations

|

Passage |

Harmonized to |

MSS |

Change |

|

Matt 10:42 |

Mark 9:41 |

D |

Adds ὕδατος |

|

Matt 13:55 |

Mark 6:3 |

K, L, W, Δ, 0106, f13 |

᾿Ιωσήφ to ᾿Ιωσής |

|

Matt 14:22 |

Mark 6:45 |

B, K P Θ, f13 |

Add αὐτοῦ |

|

Matt 14:24 |

Mark 6:47 |

, C, L, W, Δ, O73, 0106, f1, Ï; D |

Several variants; see apparatas |

|

Matt 15:36 |

Mark 8:6 |

C, L, W, Ï |

Add αὐτοῦ |

|

Matt 16:13 |

Mark 8:27 |

D,E, F, G, H, L, O, Δ, Σ, Θ, f1, f13, Ï |

Add μέ |

|

Matt 17:21 |

Mark 9:29 |

2, C, D, L, W, Δ, f1, f13, Ï |

Add the words from Mark 9:29 |

|

Matt 19:7 |

Mark 10:4 |

, D, L, Z, Θ, f1 |

Omits αὐτήν |

|

Matt 19:16 |

Mark 10:17 |

C, E, F, G, H, W, Θ, Σ, Δ, f13, Ï |

Add ἀγαθέ |

|

Matt 19:17 |

Mark 10:18 |

C, E, F, G, H, W, Δ, Σ, f13, Ï |

Substitutes the words from Mark 10:18 |

|

Matt 20:17 |

Mark 10:32 |

, D, L, Z, Θ, f1, f13 |

Omits μαθητάς |

|

Matt 20:22 |

Mark 10:38 |

C, E, F, G, H, K, M, O, U, V, W, X, Γ, Δ, Π, Σ, Φ, 0197, Ï |

Add the words from Mark 10:38 |

|

Matt 20:30 |

Mark 10:47 |

, L, N, Σ, Θ, f13 |

Add ᾿Ιησοῦ |

|

Matt 21:39 |

Mark 12:8 |

D, Θ |

Order conformed to Mark’s |

|

Matt 22:23 |

Mark 12:18 |

2, E, F, G, H, K, L, O, Σ, Θ, f13 |

Add article before λέγοντες |

|

Matt 22:32 |

Mark 12:27 |

, D, W |

Article omitted. |

|

Matt 23:13 |

Mark 12:40 |

E, F, G, H, O, W, Σ, 0102, 0107, 0233, f13, Ï |

Add Mark 12:40 |

|

Matt 24:36 |

Mark 13:32 |

*, 2, B, D, Θ, f13 |

Add οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός,? |

|

Matt 27:46 |

Mark 15:34 |

, B, 33 |

Changed to ᾿ελωϊ |

|

Mark 1:8 |

Matt 3:1 |

A, D, E, F, G, L, P, W, Σ, f3, f13, Ï |

Add ἐν |

|

Mark 1:11 |

Matt 3:17 |

, D |

Omit ἐγένετο |

|

Mark 1:29 |

Matt 8:14 |

B, D, W, Σ, Θ, f1, f13 |

Changes participle and verb to the singular. |

|

Mark 2:16 |

Matt 9:11 |

, C, L, Δ, f13 |

Add ὁ διδάσκαλος ὑμῶν |

|

Mark 2:22 |

Matt 9:17 |

, A, C, D, E, F, G, H, L, W, Δ, Σ, Θ, f1, f13, Ï |

Adds ἐκχεῖται |

|

Mark 2:22 |

Matt 9:17 |

W |

Adds βάλλουσί |

|

Mark 2:26 |

Matt 12:4 |

D, W |

Omit reference to Abiathar |

|

Mark 5:1 |

Matt 8:28 |

A, C, E, F, G, H, Σ, f13, Ï |

Changed to Γαδαρηνῶν |

|

Mark 6:3 |

Matt 13:55 |

Ì45, Σ, f13, 33 |

Assimilated to τοῦ τέκτονο ὑιός και |

|

Mark 6:39 |

Matt14:19 |

, B, Θ, O187 |

Changed to the active to the passive ἀνακλιθῆναι |

|

Mark 6:41 |

Mat 14:19 |

, B, L, Δ, 0187, 33 |

Omit αὐτοῦ |

|

Mark 7:24 |

Matt 15:21 |

, A, B, E, F, G, H, N, Σ, f1, f13, 33, Ï |

Add καὶ Σιδῶνος |

|

Mark 7:28 |

Matt 15:27 |

, A, B, E, F, G, H, L, N, Δ, Σ, 0274, f1, 33, Ï |

Add ναί |

|

Mark 8:10 |

Matt 15:39 |

D, D2, W, Σ |

Change μέρη to ὅρια |

|

Mark 8:10 |

Matt 15:39 |

D, D2, Θ, f1, f13 |

Change Δαλμανουθά to Μαγδάλα or Μελεγάδα |

|

Mark 8:15 |

Matt 16:6 |

Ì45, C, 0131, f13 |

Add καί |

|

Mark 8:16 |

Matt 16:7 |

A, C, L, Θ,0131, f13, Ï |

Add λέγοντες |

|

Mark 8:16 |

Matt 16:7 |

, A, C, L, Θ, f13, Ï |

Change 3rd per to 1st per. |

|

Mark 9:42 |

Matt 18:6 |

A, B, C2, E, F, G, H, L, N, W, Θ, Σ, Ψ, f1, f13, Ï |

Add εἰς ἐμέ |

|

Mark 10:1 |

Matt 19:1 |

C2, D, G, W, Δ, Θ, Σc, f1, f13 |

Omit καί |

|

Mark 10:2 |

Matt 19:3 |

, A, B, C, E, F, G, H, K, L, N, W, Γ, Δ, Θ, Σ, Ψ, f1, f13, Ï |

Add προσελθόντες φαρισαῖοι or some variation |

|

Mark 10:7 |

Matt 19:5 |

A, C, D, E, F, G, H, L, N, W, Δ, Σ, Θ, f1, f13, Ï |

Add the rest of the citation from Gen 2:24 as in Matt |

|

Mark 10:19 |

Matt 19:18 |

B, W, Δ, Σ, Ψ, f1, f13 |

Omit μὴ ἀποστεπήσης |

|

Mark 10:34 |

Matt 20:19 |

A, E, F, G, H, N, W, Θ, Σ, 0233, f1, f13 |

Change to τῇ τρίτῃ ἡμvερᾳ |

|

Mark 10:40 |

Matt 20:23 |

*,2, Θ, f1 |

Add ὑπὸ τοῦ πατρός μου |

|

Mark 11:24 |

Matt 21:22 |

D, Θ, f1 |

Changed to λημvψεσθε |

|

Mark 11:26 |

Matt 6:15 |

A, C, D, E, F, G, H, N, Θ, Σ, 0233, f1, f13, 33, Ï |

Add Matt 6:15 |

|

Mark 13:22 |

Matt 24:24 |

, A, B, C, E, F, G, H, K, L, W, X, Δ, Π, Σ, Ψ, 0235, f1, Ï |

δώσουσιν for ποιήσουσιν? |

|

Mark 13:32 |

Matt 24:36 |

, D, W, Θ, f1, f13 |

replaces ἤ τῆς with καί |

|

Mark 13:32 |

Matt 24:36 |

Δ, Θ, Φ |

Add μόνος |

|

Mark 14:4 |

Matt 26:8 |

D, Θ |

οἱ μαθηταὶ αυτοῦ for τινες |

|

Mark 14:25 |

Matt 26:29 |

, C, D, L, W, Ψ |

Omits οὐκέτι |

|

Mark 14:30 |

Matt 26:34 |

, C, D, W |

Omits δίς |

|

Mark 14:65 |

Matt 26:68 |

W, Δ, Θ, f13, 33 |

Add τίς ἐστvιν ο παίσας σε with minor variations |

|

Mark 14:68 |

Matt 26:71 |

, B, L, W, Ψ |

Omit καὶ ἀλέκτωρ ἐφώνησεν |

|

Mark 14:72 |

Matt 26:74 |

, C, L |

Omit ἐκ δευτέρου |

|

Mark 14:72 |

Matt 26:75 |

, A, C |

Change ἐκλαίεν to ἐκλαύσεν |

|

Mark 15:10 |

Matt 27:18 |

B, f1 |

Omit οἱ ἀρχιειρεῖς |

|

Mark 15:12 |

Matt 27:22 |

, B, C, W, Δ, Ψ, f1, 13, 33 |

Omit θέλετε |

|

Mark 15:12 |

Matt 27:21 |

A, D, E, F, G, H, N, Θ, Σ, 0250, Ï |

Add θέλετε; alternative to the omission |

|

Mark 15:25 |

Matt 27:36 |

D |

ἐφυλάσσον instead of ἐσταύρωσαν |

|

Mark 15:34 |

Matt 27:46 |

A, C, E, F, G, H, P, Δ, Θ, f1, f13, 33, Ï |

Reverse order of ἐγκατέλιπες με |

|

Mark 15:39 |

Matt 27:50 |

A, C, D, E, G, H, N, Δ, 0233, f1, f13, 33, Ï |

Include κράξας |

1 Mark 13:32 has ἢ τῆς (Å D W Θ f1 f13 157 pm it syrs, p sa bopt read καί) instead of καί, ἐν οὐρανῷ instead of τῶν οὐρανῶν, and lacks μόνος (Δ Θ Φ 13. 565 pc sa bopt add μόνος). These differences can be significant in determining which passage the church fathers are quoting. Of these three differences the reflection of μόνος should be the deciding factor. The reflection of καί is virtually negligible since the church fathers usually reflect καί rather than ἢ τῆς even when its clear the father is citing Mark 13:32. Note that these differences have been virtually ignored in Alexander Roberts, & James Donaldson, eds., Ante-Nicene Fathers, vols. 1-10 (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1867-72; reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1994); Philip Schaff, ed., Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vols. 1-14 (New York: Christian Literature, 1886-90; reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1994); Philip Schaff, & Henry Wace, eds., Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vols. 1-14 (New York: Christian Literature, 1890-1900; reprint, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1994) despite the fact that the editors and translators were aware of the textual problem.

2 Adversus haereses 2.28.6 omits the reference to the angels, οὐδὲ οἱ ἄγγελοι τῶν οὐρανῶν. Irenaeus may be quoting from memory.

3 De Principiis 198E.2.6.1.139.17

4 Ancoratus 22.4.3; Panerion 3.165; 3.191.8

5 Commentarii in Zacharian 5.78.6 (οὐτέ instead of οὐδέ)

6 Responsiones ad Tiberium diaconum sociosque suos 583.19; Trin. 75.20.57; 75.368.46; 75.377.34t

7 Hom. Matt. 77.1. Chrysostom omits μόνος but retains τῶν οὐρανῶν. It may be that he actually has Mark 13:32 in mind even though the homily is on Matt 24:32-36.

8 Trin. 1.29; 9.2, 58 all reflect ἐν οὐρανῷ rather than τῶν οὐρανῶν. He also may be quoting from memory. Whether he has Matt 24:36 or Mark 13:32 is another question. Because he reflects Matthew’s μόνος, it is more likely that he unconsciously assimilated Matthew to Mark.

9 Fid. Grat. 5.5.192 also reflects ἐν οὐρανῷ rather than τῶν οὐρανῶν.

10 Enarrationes in Psalmos 38.6.1.9

11 Commentarii in euangelium Matthaei 590.4.591

12 It is possible that the Latin text of Origen represents the Caesarean textttype, which would make the distribution over three regions. If Chrysostom is referring to Matt 24:36, then the distribution is in the fourth century over all four regions.

13 Disputatio contra Arium 26.472.52. This text is supposedly a report of Athanasius’ debates with the Arians at the council of Nicea. document is most likely spurious because Athanasius was only a deacon under Alexander, bishop of Alexander, and it is unlikely that he would have even been given the opportunity to speak, much less have a long-winded debate with Arius. It is even disputed that Athanasius was even at the Council of Nicea.

14 Trin. 39.917.8. The text also has ἢ τῆς instead of καί.

15 Commentarii in euangelium Matthaei 590.4.590

16 Commentarii in euangelium Matthaei 590.4.591

17 Fid. Grat. 5.5.192

18 Adversus Arium et Sabellium de patre et filio 3.76.26. His text reads: Οὐδεὶς οἶδὲ τὴν συντελεστικὴν ἡμέραν καὶ τὴν ὥραν, οὐδ᾿ οἱ ἄγγελοι τῶν οὐρανῶν οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός, ἐν τοὶς κατὰ Μάρκον εἰρημένοις, εἰ μὴ ὁ πατὴρ μόνος… Gregory cites Matthew but attributes οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός to Mark.

19 Epistula 236.28.

20 Again, if Origen’s text is Caesarean, then the distribution is early over all four regions.

21 While υἱός and πατήρ commonly are denoted with nomina sacra, both Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus spell the terms out; therefore, their example is followed.

22 The first corrector drew a line over oudeouios to denote that he believed the phrase should not be present. The second corrector apparently attempted to erase the line to show his judgment.

23 cf. Daniel B. Wallace, “The Greek New Testament according to the Majority Text: A Review Article,” GTJ 4, no. 1 (Spring 1983): 125. See also Henry Alford, Revised by Everett F. Harrison, The Greek New Testament, vol 1 (Chicago: Moody Press, 1958), 245; W. C. Allen, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Gospel according to S. Matthew, 3rd ed., ICC, ed. S. R. Driver, A. Plummer, & C. A. Briggs (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1912), 260; Alfred Plummer, An Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel according to St. Matthew (London: Robert Scott, 1915; reprint, Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1982), 339.

24 See Craig L. Blomberg, Matthew, NAC, ed. David S. Dockery, vol. 22 (Nashville: Broadman, 1992), 365; Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: The Churchbook: Matthew 13-28, vol. 2 (Dallas: Word, 1990), 879-80; D. A. Carson, “Matthew,” in EBC, ed. Frank E. Gabelein, vol. 8 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1984), 508; W. D. Davies, and Dale C. Allison, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Gospel according to Matthew, vol.3, XIX-XXVIII, ICC, ed. J. A. Emerton and C. E. B. Cranfield (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1997), 377; Robert H. Gundry, Matthew: A Commentary on His Handbook for a Mixed Church under Persecution, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 491-92; Donald A. Hagner, Matthew 14-28, WBC, ed. David A. Hubbard and Glenn W. Barker, vol. 33B (Dallas: Word, 1995), 709.

25 Blomberg, Matthew, 365 argues that it was omitted by scribes with a docetic christology.

26 Apparently, Metzger believes οὐδὲ…οὐδὲ…must be a correlative pair. But this is not at all necessary. Matthew uses the single οὐδέ with the meaning “not even” in several places (6:28; 21:32; 25:45; 27:14). It also makes good theological sense because it was commonly believed that God kept counsel with the holy angels, although he did not necessarily reveal the hour of Israel’s deliverance (4 Ezra 4:52; b. Sanh.99a). Curiously, Carson, “Matthew,” 508 believes that Metzger’s grammatical argument is the strongest for the inclusion, although he does not explain why.

27 The table records probable scribal harmonizations between Matthew and Mark. These are not all the possible harmonizations, but it does include most of probable ones that involve the major manuscripts.

28 See footnote 1.

29 Athanasius, Orationes contra Arianios 3.28.42-50.

30 Athanasius, Disputatio contra Arium 27.473.52-54.

31 Gregory of Nazianzus, De filio 30.4.15-16.

32 Basil, Epistula 236.

33 John Chrysostom, Hom. Matt. 77.1.

34 Ambrose, Fid. Grat. 5.5.192.

35 Hilary of Poitiers, Trin. 9.58-66.

36 Augustine, Trin. 1.12.

37 BDF §448.8; A. T. Robertson, A Grammar of the Greek New Testament in the Light of Historical Research (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1934), 1024-25; M. Zerwick, Biblical Greek Illustrated by Examples, 4th ed. (trans. Joseph Smith: Rome: Pontificii Istituti Biblici, 1963), §468-71.

38 For further discussion of εἰ μή clauses see Charles E. Powell, “The Semantic Relationship between the Protasis and the Apodosis of New Testament Conditional Constructions” (Ph.D. diss., Dallas Theological Seminary, 2000), 180-207; “Εἰ Μή Clauses in the New Testament: Interpretation and Translation” (paper presented at the national annual meeting of ETS, 2000), 1-17.

39 Other examples include Matt 12:39; 15:24; 16:4; Luke 11:29; John 3:13; 10:10; Rom 7:7; 13:8; 1 Cor 1:14; 2:2; 12:3, 5, 13; Gal 1:7; Eph 4:8; 1 John 2:22; Rev 2:17; 14:3; 19:12.

40 Πάντα μοι παρεδόθη ὑπὸ τοῦ πατρός μου, καὶ οὐδεὶς ἐπιγινώσκει τὸν υἱὸν εἰ μὴ ὁ πατήρ, οὐδὲ τὸν πατέρα τις ἐπιγινώσκει εἰ μὴ ὁ υἱὸς καὶ ᾧ ἐὰν βούληται ὁ υἱὸς ἀποκαλύψαι. All things have been handed over to me by My Father; and no one knows the Son, except the Father; nor does anyone know the Father, except the Son, and anyone to whom the Son wills to reveal him.

41 Donald A. Hagner, Matthew 1-13, WBC, ed. David A. Hubbard and Glenn W. Barker, vol. 33A (Dallas: Word, 1993), 320.

42 Several scholars recognize the tension and argue that it is a deep, intimate knowledge between the Father and the Son that is exclusive. While this is close to the point, it still suffers from the assumption that εἰ μή must mean “except.” See Leon Morris, The Gospel according to Matthew, Pillar Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 293-94; John Nolland, Luke 9:21–18:34, WBC, ed. Glenn A. Hubbard (Dallas: Word Books, 1993), 273-75.

43 J. K. Baima, “Making Valid Conclusions from Greek Conditional Sentences” (Th.M. thesis: Grace Theological Seminary, 1986), 64-65.

44 Morris, Matthew, 366-67.

45 Baima, “Making Valid Inferences,” 62-63.

46 Basil, Epistula 236.

47 The text reads περὶ δὲ τῆς ἡμέρας ἐκείνης ἢ ὥρας οὐδεὶς οἶδεν, οὔτε οἱ ἄγγελοι τοῦ Θεοῦ, ἀλλ᾿' οὐδ᾿ ἄν ὁ Υἰός ἒγνω, εἰ μὴ ὁ πατήρ. By adding ἀλλά and ἄν ἔγνω to the apodosis, the implied verb in the protasis is then understood to be ἔγνω rather than οἶδεν.

48 The reason they chose to drop οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός rather than μόνος may be to preserve Matthew’s style of using μόνος, especially in εἰ μή clauses in the exclusive sense. See Matt 12:4; 17:8; 21:19. The reasons for the omission of οὐδὲ ὁ υἱός in Mark 13:32 by X and a few other Greek MSS may be either accidental, or due to theological motivation because of not being familiar with the preeminent understanding of εἰ μή clauses, or possibly due to harmonizing the text to Matt 24:36, since more than likely those manuscripts did not include the phrase there either.

Related Topics: Textual Criticism

Charismata and the Authority of Personal Experience

Related MediaThis is part of a series of occasional short essays from the "Professor's Soap Box." It is not intended to be a detailed exposition; rather, it is meant to give you food for thought and to challenge some popular ideas.

Introduction

Have you noticed the rise in psychic "hotlines" and TV shows nowadays? Five years ago, it would have been difficult to find even a psychic commercial on TV. Now, there are several half-hour infomercials, aired almost round the clock.

Have you also noticed New Age music cropping up here and there, not to mention the infiltration of Eastern Mysticism into the West, and increased UFO sightings (not to mention TV programs about them)? How about the rise of "what's in it for me" attitudes, a morality of convenience, and a market-driven society (i.e., making a living as an end in itself)? While we're at it, we could add the increasing denial of absolute truth by most Americans--even though a large proportion claim to be evangelical Christians, the prioritizing of relevance over truth, of pragmatics over knowledge, of feelings over beliefs. Al Franken, of Saturday Night Live fame, some years ago epitomized what we are seeing with his self-serving commentary (he humorously suggested that this decade should be labeled the "Al Franken" decade).

A New Kind of Charismatic

Part and parcel of this phenomenon is the rising popularity of charismatic Christianity--especially among those who had never been attracted to the charismatic movement before. Specifically, the Pentecostal/charismatic movement historically has roots in Wesleyan theology and practice. In other words, it has historically been associated with Arminian theology. The reason for this is not immediately obvious, but can be seen through a variety of connections. Arminianism teaches, among other things, that a person once saved can lose his salvation. Hence, Arminians put a strong emphasis on moral duty, as well as spiritual experiences, as the continued confirmation that one is still saved. It is a natural extension from this stance that the test by which a person knows he is saved is various manifestations of the Spirit. Thus the craving for supernatural experiences is both endemic to the charismatic mindset and necessary as continued confirmation of salvation.

But this craving for confirmation is not the motivation of many who have become charismatics in the last few years. Indeed, what is unusual about the current popularity of the charismatic movement, principally the Vineyard form, is that has attracted many Calvinists as well as many well-trained scholars. Every year at the Evangelical Theological Society meetings1 I learn of a few more professors of theology who have joined the ranks of the Vineyard movement. Often, the response of colleagues when they find out about one these theologians is one of astonishment: "No! Not him! I never would have expected him to become a charismatic!"

Cognitive Christianity

and the Impoverished Soul

Why are scholars suddenly becoming charismatics? What has happened in the last few years to attract the intelligentsia to this group?

We can give both a short answer and a long one. The short answer is that many Christian scholars have for a long time embraced a Christianity that is almost exclusively "from the neck up." That is, theirs is a cognitive faith, one where reason reigns supreme. They are usually fine exegetes and theologians, able to defend the faith and articulate their views in a coherent, biblical, profound, and logical way. But (without naming names) many of these savants have lost their love for Christ. They love the Bible and know it inside and out. But their soul has become impoverished. They love God with their mind only; that is the extent of their spiritual obligation as they see it. In fact, for them, personal experience--especially of a charismatic sort--is anathema. It has no place in the Christian life. Study of the Bible so that they can control the text is what the Christian life is all about.

But when crisis comes--such as the death of a loved one, a teenage daughter's pregnancy, or some major upheaval in their church ministries--their answers appear shallow and contrived, both to others and themselves. They have the inability to hurt with the hurting, though they know all the right verses on suffering! They begin to search for answers themselves, answers of an entirely different sort. Often, in the crucible of the crisis, they attend a charismatic meeting. And there, a "prophet" reveals something about their life. They are both amazed at the prophecy and deeply touched at the perception into their own condition. (Of course, cognitive types almost always marvel when other, more sensitive people, intuitively recognize traits and characteristics, internal workings and struggles in others.) Their souls get drenched with an emotional infusion that had been quenched for too long. It doesn't take long before they hold hands with those whom they used to oppose, even to the point of now leading charismatic groups. They in fact become the theologians of a new breed of charismatic, giving a rather sophisticated rationale for charismata. In the process, they have gone through a paradigm shift: their final authority is no longer reasoning about the Scriptures; now it is personal experience.

Because of a crisis, personal, spiritual experience has replaced reason as the authority that guides their lives. They have exchanged, in some measure, their heart for their mind.2 That's the short answer.

The Age of Epistemological Narcissism

The long answer is this. The history of the Church and indeed of western civilization, in terms of authority, can be traced out rather simply.3 Before the Reformation, tradition was the final authority. This included the tradition of the Roman Catholic Church and all its trappings. When that pesky little German monk, Martin Luther, nailed his ninety-five theses to the door of the Wittenberg church, a new authority was boldly announced: revelation. Actually, it was an old authority, but one which Luther and later Calvin, Zwingli, Melanchthon, and a host of others, argued had been subverted to tradition by the Church in Rome. The Reformation's battle cry was sola scriptura--that is, Scripture alone is our authority. The Roman Church argued that we needed tradition, especially the interpretations offered by church fathers, in order to understand Scripture. This was so, they argued, because the Bible could not be easily grasped. The Reformers argued for the perspicuity of Scripture--that it was sufficiently clear to be a good guide in essential matters, such as the person of Christ, the Trinity, salvation. In order to prove the point they needed to exercise reason. New hermeneutical methods were developed, translations were made, commentaries were written. All of this was consistent with the view that the Bible should be clearly understood. The Reformers knew it to be so in their study; they wanted to make it so for the person in the pew.

As long as reason was the handmaid of revelation, there was no problem. But once reason became master, revelation was increasingly viewed as unnecessary and, in fact, untrue. With the birth of the Enlightenment came the promise of a new king. He would soon reign over virtually all human thought in the western world.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Enlightenment had so captured the evangelical community that the Bible became more an object of study than a guide to life. Seminaries in this century followed largely the Princeton model (a strongly Calvinist school) of reasoning about the Scriptures. Pastors were trained to expound the text of Scripture--and this came to mean explain the text, but not apply the text. Too many seminaries viewed one's exegetical and theological skills as the lone spiritual barometer. There was no accountability of one's life. Whether one believed the Bible and consequently tried to shape his life by its precepts was often not in view.

The problem with this model was that non-evangelical scholars could also do first-rate exegesis. Many of these non-evangelical savants would be considered nonbelievers: besides rejecting the Bible as the Word of God, they did not embrace the bodily resurrection of Christ or, sometimes, even the existence of God. Hence, if quality exegesis was an indicator of spirituality, then an atheist might be considered spiritual! The barometer of mere knowledge obviously has its defects, for without belief there is no life. Cognition is important for true biblical scholarship; but without conversion as a first step, such is certainly not evangelical biblical scholarship. Further, this approach trickled down to the pew: for many churches, even today, mere Bible knowledge, regardless of its application to one's life, is equated with true spirituality. Reason has come to reign over revelation even for evangelicals.

With the advent of postmodernism, reason has increasingly become passé. It's not necessarily that reason is rejected as untrue; rather, it is judged to be irrelevant. So what authority is left? What authority remains after tradition, revelation, and reason have all been abandoned? Personal experience. Ours is the age of epistemological narcissism. This is no longer the age of cogito ergo sum ("I think; therefore, I am"—the hallmark of Cartesian logic); it has become the age of sentio ergo sum ("I feel; therefore, I am"). And since there are no external standards by which to judge personal experience (since other authorities are rejected), anything goes--whether it be sensuality or hallucinogenic existence, full-blown mysticism or an uncritical embracing of supernatural phenomena from any and all corners.

So, how does the current charismatic movement fit into this? Why are so many intellectuals embracing the charismata? It seems that the vacuum left in their souls by a rationalistic faith has made them ripe for a different kind of authority. As sons of the Enlightenment, these cognitive scholars have embraced reason as the supreme authority in their lives. But the rationalism of the Enlightenment is, when unbridled, antithetical to revelation. These scholars viewed personal experience as the enemy of the gospel, while embracing reason as its friend. But when some crisis invades their lives, and their purely cognitive faith cannot supply the deepest answers (for it does not address the whole man), they have to find the answers some place. And they look to an entirely different authority. They are ripe for excess in one area, just as they had lived in excess in another. Ironically, they end up mirroring the present age of postmodernism, just as they had mirrored the past one of rationalism.

In reality, both personal experience and reason are part of proper human existence. Like fire, they can be used for good or evil. When they take on the role of supreme authority, consciously or not, they destroy.4 "I know" and "I feel" must bow to "I believe." (When either one is elevated above revelation it produces arrogance.) The cognitive content of that belief is the revealed Word of God. It requires diligent study to grasp its meaning as fully as mere humans can grasp it. But it will not be believed unless there is a personal experience with the Risen One. Thus, the trilogy of authority can be seen this way: both personal experience and reason are vital means to accessing revelation. We are to embrace Christ, as revealed in the Word, with mind and heart.5 When either reason or experience attempts to escape the supreme sovereignty of the revealed Christ, the individual believer starts down a path of imbalance. Tragically, his service to the Lord Christ is thereby increasingly curtailed.6

1 The Evangelical Theological Society is a group of evangelical leaders, principally professors at seminaries and evangelical colleges. Full membership requires subscription to a minimal core of doctrines and a Th.M. (Master of Theology) degree or its equivalent.

2 This does not mean that these scholars no longer use their brains! But it does mean, for many of them, that reason is subordinated to personal experience in an epistemological hierarchy.

3 I owe the framework of the "long answer" to Dr. Bob Pyne, professor of Systematic Theology at Dallas Seminary. He is not to be blamed for the details, however!

4 Most charismatics today would argue that their personal experiences are fully subordinate to revelation. But most cognitive Christians would also argue that reason for them is subordinate to revelation.

5 Thus far I have left tradition out of the equation. This is, however, something of an overstatement. In reality, most of us employ tradition as a conduit to another authority. Often we are unaware of the tradition's influence. Those in Bible churches worship in a way quite different from those in more liturgical settings; Koreans worship in a way that is markedly different from African-Americans. And a given group may tacitly assume that somehow its worship style is the right one, or that others are wrong because they are different. The difference between evangelical Protestants and Roman Catholics with reference to tradition is that evangelical Protestants generally feel more at liberty (and more responsible) to question their tradition, and to change it in line with what they perceive is the biblical norm. In other words, they are able, when it is brought to the conscious level, to subordinate tradition to revelation.

6 You will notice that I have not in this paper given any arguments against the charismatic movement. This paper is instead intended to set the stage, giving a rationale for why so many are flocking toward this kind of Christianity. In later papers we will address specific charismatic arguments. Suffice it say here that our thesis should be clear: What is endemic to the modern charismatic movement is an elevation of personal experience above revelation as final authority.

Related Topics: Spiritual Gifts, Tongues

The Church in Crisis: A Postmodern Reader

Related MediaThe evangelical church is in a crisis today. Some see it as teetering on a precipice, its demise merely decades away unless severe counter-measures are taken. The overt pragmatism, separation of “religious truth” from “real truth,” and marginalization of the Lordship of Christ and the authority of scripture are a large part of the reason for this crisis. At bottom, the church has moved to the back of the intellectual bus by elevating personal experience as the ultimate measure of truth. All of this is playing into the hands of the god of this world. A growing number of evangelical (and even non-evangelical and non-Christian) voices are being raised against such cultural forces, asking us to return to a worldview that is more balanced. Too many Christians are either unaware of their assimiliation into culture or else do not have ready access to viewpoints that sufficiently counter it. This all-too-brief reading list is offered as a partial corrective, in hopes that some in the church today will begin to read—and in hopes that some believers who have material wealth may see the great need to help fund large projects that cultivate the life of the mind.

The following annotated bibliography addresses issues related to postmodernism. Some of the works are more general, pointing to the larger issues of epistemology (how we know), common sense vs. political correctness, the life of the mind, and the authority of scripture in guiding our lives. But all of these books address a common theme: culture and its adverse impact today. This is not to say that culture has only a negative impact (although one or two of the authors seem to think this!), but it is to say that much of culture has a negative impact and that the Church, more than any other group, should be wary of such. As Paul told the Romans long ago, “Do not become conformed to this age, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind” (Rom 12:2). The ten books are listed in recommended reading order.

(1) Moreland, J. P. Love Your God with All Your Mind. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1997.

Moreland is professor of philosophy at Talbot Seminary. In this book he gives biblical, theological, historical, and philosophical reasons why Christians need to begin to think again. Two quotations at the beginning of the book (p. 19) summarize well what it’s about:

R. C. Sproul: “We live in what may be the most anti-intellectual period in the history of Western civilization. . . . We must have passion—indeed hearts on fire for the things of God. But that passion must resist with intensity the anti-intellectual spirit of the world.”

1980 Gallup Poll on Religion: “We are having a revival of feelings but not of the knowledge of God. The church today is more guided by feelings than by convictions. We value enthusiasm more than informed commitment.”

(2) Packer, J. I. Truth and Power: The Place of Scripture in the Christian Life. Wheaton: Shaw, 1996.