Prologue: William Tyndale—The Father of the English Bible

Related Media“Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

Those were his last words. This was his last prayer.

The date is October 6, 1536. The location is the town of Vilvoorde, near Brussels in Belgium. The occasion is the execution of William Tyndale, age 42. One historian re-enacts the scene for us.

The sun had barely risen above the horizon when he arrived at the open space, and looked out over the crowd of onlookers eagerly jostling for a good view. A circle of stakes enclosed the place of the execution, and in the center was a large pillar of wood in the form of a cross and as tall as a man.

A strong chain hung from the top, and a noose of hemp was threaded through a hole in the upright. The attorney and the great doctors arrived first and seated themselves in state nearby. The prisoner was brought in and a final appeal was made that he should recant.

Tyndale was immovable, his keen eyes gazing toward the common people. A silence fell over the crowd as they watched the prisoner’s lean form and thin, tired face; his lips moved with a final impassioned prayer that echoed around the place of execution, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

His feet were bound to the stake, the iron chain fastened around his neck, and the hemp noose was placed at his throat. Only the Anabaptists and lapsed heretics were burnt alive. Tyndale was spared that ordeal.

Piles of brushwood and logs were heaped around him. The executioner came up behind the stake and with all his force snapped down upon the noose. Within seconds Tyndale was strangled.

The attorney stepped forward, placed a lighted torch to the tinder, and the great men and commoners sat back to watch the fire burn. Not until the charred form hung limply on the chain did an officer break out the staple of the chain with his halbert, allowing the body to fall into the glowing heat of the fire; more brushwood was piled on top and, while the commoners marveled “at the patient sufferance of Master Tyndale at the time of his execution,” according to Foxe, the attorney and the doctors of Louvain moved off to begin their day’s work, never imagining that within months at least part of the plea in Tyndale’s dying prayer would be answered affirmatively.1

Who was this Tyndale and what had he done to warrant such violence?

He was faithful unto death. But why such injustice? What exactly was his crime? Was it worth it? What good did he really do? His life and times tell us the story.

Tyndale’s Life and Times

“If God spares my life, ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plow shall know more of the Scriptures than thou dost.”

Nothing more clearly defines the life and work of Tyndale than these words, spoken before he left England to undertake his life’s work. Shocked by the ignorance of both the clergy and laity, he became convinced that only if the Scriptures were available to them in English would the people be established in the truth. The Bible of his day was in Latin, one thousand years old. Few understood it, read it or had access to it. The only English translation available was the hand-copied Wycliffe Bible that was secretly distributed by the Lollards, followers of the fourteenth-century John Wycliffe. But it had never been printed, and, having been translated only from the Latin Vulgate, it was inaccurate in many ways.

Herein lies Tyndale’s greatest contribution. He profoundly influenced our history, becoming a major player in the great English Reformation. The English rapidly became a “people of the Book.” That book was the Bible, translated, printed and distributed by Tyndale in the language of the people. We are enormously in his debt.

It is generally believed that it was about 1494 when William was born to a Tyndale family in Gloucestershire, near the Welsh border.

Our first hard facts locate him in Magdalen Hall, attached to Magdalen College of Oxford University, where he studied languages and theology, obtaining both his B.A. (1512) and M.A. (1515) before moving to Cambridge to continue his studies. It was here that his Protestant convictions were strengthened. He may well have participated in the lively discussions at The White Horse, the famous pub where Luther’s theses of 1517 and subsequent articles were studied and debated. His name is associated here with Ridley, Cranmer and Coverdale—all Cambridge men.

Dissatisfied with the teaching of theology at the universities, he left that world in 1521 and became a tutor in the household of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury Manor, near Bath. It was here that Tyndale was shocked by the biblical ignorance of the clergy. To one such cleric he declared, “If God spare my life, ere many years pass, I will cause a boy that driveth the plow shall know more of the Scriptures than thou dost.”

Tyndale was beginning to clearly feel the call of God upon him to translate the Scriptures into English and distribute them to the common people.

This, however, was against the law. Because of the church’s perceived threat from the Lollards, in 1408 the church banned the translation of the Bible into English.

It was a crime punishable by death. One day in 1519 the church authorities publicly burned a woman and six men for nothing more than teaching their children English versions of the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments and the Apostle’s Creed. In search of ecclesiastical approval, Tyndale obtained an interview with the bishop of London, Cuthbert Tunstall, but received no encouragement at all. Tyndale concluded, “[N]ot only was there no room in my lord of London’s palace to translate the New Testament, but there was no place to do it in all of England.”

Why such opposition? One historian writes:

The church would never permit a complete printed New Testament in English from the Greek, because in that New Testament can be found neither the Seven Sacraments nor the doctrine of purgatory, two chief sources of the church’s power.2

Tyndale left England never to return.

In April, 1524, Tyndale left England never to return. Supported by a group of wealthy London cloth merchants, he travelled to the Continent to engage in his work of translation.

Arriving in Hamburg, Germany, he worked on the New Testament, which was ready for printing the next year. The printing began in Cologne, only to be stopped by a police raid prompted by anti-reform church authorities. Fortunately Tyndale had been warned of the raid and fled just in time with the pages he had printed. A few fragments were left behind and confiscated. Only one copy of this incomplete edition has survived.

In 1526 Tyndale moved to Worms, a more secure and friendly city. Here the first complete New Testament in English was published. Of the 6,000 copies printed, only two have survived. One has been purchased by the British Library for one million pounds.

Getting the illegal New Testament into the hands of the English people was the next challenge. Fortunately there existed an established underground system for smuggling in censored books. They were shipped to England, hidden by dock workers in the cargo of English merchants who were sympathetic with the Reformation, then distributed in England by those merchants.

It is not surprising that so few copies survived. Church authorities did all they could to eradicate them. In 1526 the Bishop of London preached against the translation and had copies burned at St. Paul’s Cathedral. In the following year the Bishop of London, encouraged by Augustine Packington, a friend of Tyndale’s, bought copies of the New Testament and had them burned. Unknown to him, the substantial sums he paid provided Tyndale with funding to produce a better, more numerous second edition of his New Testament!

In 1530 Tyndale’s translation of the Pentateuch was printed at Antwerp in Belgium, where he had settled, a centre like Cologne, which was a great port city with thriving trade lines to England. Here he continued his translation of the Old Testament and made several revisions of his New Testament. It also provided greater security for him . . . but only for a time.

Tyndale’s Arrest and Trial

“Here thou hast (most dear reader) the new testament or covenant made with us of God in Christ’s blood.”

Prologue

Tyndale’s Revised New Testament, 1534

For security reasons, in 1534 Tyndale moved into the home of Thomas Poyntz, a relative of Lady Walsh of Little Sodbury, an Englishman who kept a house of English merchants. Here Tyndale completed his most significant revision of the New Testament (1534). It is the New Testament as English readers and speakers have known it until the last few decades of the twentieth century.

While staying in Poyntz’s home he befriended Henry Philips, an Oxford graduate who had fallen into extreme disgrace and poverty, then living in neighbouring Louvain. Louvain was a strong centre of Roman Catholicism and very antagonistic to the Reformation. Why did Philips now have sufficient money to enable him to live comfortably? Someone in London had paid him handsomely to carry out a secret operation of betrayal. He was to become like Judas, betraying his close friend.

En route to dinner together one day, Philips pointed with his finger over Tyndale’s head, indicating to officers planted at the entrance to Poyntz’s house whom they should arrest. Tyndale was imprisoned in the secure castle of Vilvoorde, six miles north of Brussels, eighteen miles from Antwerp, where he remained until his death.

In the following 450 days, evidence was gathered and charges were laid. For Tyndale those were long days of interrogation about his life, his beliefs and especially about his books and letters. Finally a formal accusation was prepared. Before seventeen commissioners Tyndale was charged with heresy, not agreeing with the Holy Roman Emperor.

In trapping Tyndale, his enemies had their biggest catch. He was a first class scholar, the prominent interpreter of Luther’s ideas to the English and the major player in spreading the “heresy” of Lutheranism in London and across the entire country.

The decisive moment had come.

The Biblical truths he had lived by for a dozen years of dangerous exile in poverty, which had driven his work of translating and writing with absolute dedication and total integrity . . . were not a matter of legal quibbles in an irregular court in a local spot in the Low Countries, but of Scripture itself, the Word of God Himself.3 (emphasis added)

The issue at stake was a familiar one: salvation by faith alone, as Tyndale, Luther and the apostle Paul maintained, or salvation by works, as the Church of Rome insisted. Rather than acknowledge his “error,” as he was expected to do, Tyndale dared to defend himself and was seen as unrepentant.

He was formally condemned as a heretic, degraded from the priesthood and handed over to the secular authorities for punishment—that is, burning at the stake. Each of these three phases were public events.

The condemnation for heresy included the public reading of the articles Tyndale had written declaring salvation by faith alone. In so doing, he demonstrated his disagreement with the Church of Rome.

The degradation of the priest followed a few days later:

... the prisoner was led on to a high platform, on which the bishops were prominent, in his priestly vestments. The anointing oil was symbolically scraped from his hands, the bread and wine of the Mass placed there and removed, and the vestments ceremonially stripped away.4

Two months later he was publicly executed, not by being burned alive, a terrible death often reserved for baser criminals, but by being strangled at the stake, after which his body was burned.

It is not without significance that the passion and purpose of his life was at the heart of his last spoken words before he was strangled: “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

One year earlier, Miles Coverdale, Tyndale’s friend, published the first ever complete printed edition of the Bible in English. For political reasons, Tyndale’s name did not appear in it, though the translation was nearly seventy percent composed of Tyndale’s work. God had already begun to answer Tyndale’s last prayer.

Less than a year after Tyndale’s martyrdom, King Henry VIII gave official approval of this Bible, and by 1539 every parish in England was required to make a copy of the English Bible available to all its people. Assured that the edition was free from heresies, Henry proclaimed, “Well, if there be no heresies in it, then let it be spread abroad among all the people!” Tyndale had won!5

Tyndale’s Legacy

I beseeche you therefore brethren by the mercifulness of God, that ye make youre bodyes a quicke sacrifise, holy and acceptable unto God, which is youre resonable servynge off God. And fassion note youre selves lyke unto this worlde. But be ye chaunged [in youre shape] by the renuynge of youre wittes that ye may fele what thynge that good, that aceptable and perfaicte will of God is. (Rom. 12:1-2, 1526 edition)

The Translator

William Tyndale was many things, but first and foremost this man of God was a translator. This was his supreme gift. The consuming passion of his life was to provide a clear and accurate translation of the Scriptures in English for the common people to own and read. His greatest contribution then was his translation of Scripture for the first time, from the original Greek and Hebrew into English, and then printing it in pocket volumes for everyone to own.

His university education prepared him for this timely task. His skill in seven languages that he spoke like a native (Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Spanish, English and French) plus familiarity with German equipped him for his scholarly work. He had two working criteria: it had to be accurate and it had to make sense. In contrast to previous and subsequent versions, Tyndale is clear. He worked hard to speak the language of the people in a crisp, vivid, understandable style. “Fluent ease of expression in simple colloquial English are the conspicuous features of Tyndale’s style.”6

His New Testament translations include the Cologne Fragment (1525), The Worms New Testament (1526) and The Revised New Testament (1534). His Old Testament work resulted in three separate sections: The Pentateuch (1530), Jonah (1531) and selected passages from the Old Testament that were appointed to be read as epistles in the liturgy (1534), appended to his New Testament. There is tradition and evidence that he also translated Joshua to 2 Chronicles as found in Matthews Bible of 1537.

The English Bible officially approved by Henry VIII within two years after Tyndale’s death was nearly seventy percent composed of Tyndale’s work. Ninety percent of his wording appeared in the King James Version published nearly 100 years later (1611). Seventy-five percent of his wording appeared in the Revised Standard Version of 1952.

C. H. Williams helps us understand the magnitude of Tyndale’s influence when he writes,

Tyndale’s translations, together with the finest passages of his original writings, went into the making of modern English prose. Milton, Bunyan and a long list of later English writers were steeped in the language of the Authorized Version and in consequence, whether they knew it or not, they were debtors to the translator of the first New Testament. The ease with which the language of the Authorized Version became merged into the English heritage had paradoxical results. The sphere of Tyndale’s influence was widened, but at the same time he was robbed of the recognition he deserved.... He found his surest triumph in the ascendancy of the 1611 text.7

The Reformer

Tyndale’s influence as a translator was great but it was not immediate. His Reformation writings, however, “were more immediately influential in marshalling Protestant opinion in England.”8

His influence came from both his own personal writings and his interpretation of Luther’s ideas to English readers. The authorities recognized the threat of these materials immediately and banned them in England by royal proclamation.

Tyndale’s first such work was the Prologue to the Epistle to the Romans, probably printed in Worms (1525). One quarter is Tyndale’s; the remainder is Luther’s. As expected, the subject is an exposition of justification by faith. It found a ready sale in England but was loudly denounced by Sir Thomas More and the authorities.

The Parable of the Wicked Mammon was his next venture (1528). The theme is an exposition of the parable of the unjust steward (Luke 16). His deeper interest in this exposition is once again the doctrine of justification by faith alone.

In 1528 The Obedience of the Christian Man was published, the largest and most important of his writings. It is a defence of the need to study the Bible—all hope for the reformation of the church depends upon an awareness of the errors in Roman theology and practice. “In his insistence on the layman’s right to read and interpret the Scriptures for himself, Tyndale was putting before his English readers the most radical challenge made in Reformation thought.”9

Here Tyndale argues that Christians have the duty of obedience to cruel authorities, except where loyalty to God is concerned.

Despite it being illegal to possess a copy of this book, Lady Ann Boleyn possessed a copy and passed it on to King Henry VIII, who loved it and said, “This book is for me and all kings to read.”

The Practice of the Prelates was the last of these writings (1530). “It is the most remarkable, and easily the most bitter of his polemical writings.”10Tyndale’s persecution has had its effect. His frustration is evident. It must be read against the dark background of the events in England during those years—Henry VIII’s determination to force a papal decision on the legality of his first marriage. The writing contains “the first outpouring of Tyndale’s pent-up thoughts about the Church of Rome, its claims to privilege, its teachings and the actions of its ministers.”11

The Controversialist

Tyndale’s tumultuous life was punctuated by violent literary clashes with Sir Thomas More, the lord chancellor, commissioned by the king and the church to refute William Tyndale’s arguments and to discredit his character.

Tyndale attacked the institutions of the Church of Rome, concentrating his attention on the errors and shortcomings of the clergy. Sir Thomas More responded with a personal attack on Tyndale’s character. The battle intensified and deteriorated over the years (1529-1533) and yielded such writings as Mores “Dialogue Concerning Heresies” (1529), Tyndale’s “Answer To More” (1531), “Mores Confutation” (1532-1533) and his “Apology” (1533).

For Sir Thomas More, the Roman Catholic Church was the true, infallible church. A heretic was anyone who opposed the church, its representatives and its teachings. Any such heretics he had burned at the stake. For Tyndale, the true and final authority was Scripture, and any person or group denying this was in league with Antichrist. It was this conviction that brought him to his violent death, but drove the movement we know as the Great English Reformation.

The Theologian

The starting point of Tyndale’s religious thinking was his convictions that the Scriptures were both authoritative and adequate. Though to many evangelicals today these seem so elementary, in his day it was simply radical, opposing the humanism of Erasmus and the traditionalism of the church.

He attacked the long established Roman method of Bible exegesis. It was based on the assumption that most sentences in the Bible could be interpreted in four senses. These were the literal sense, which explains the historical content of the text; the tropological sense, which teaches what we ought to do; the allegorical sense, which reveals the metaphorical implications of the text in order to explain matters of faith; and lastly there was the anagogical sense which dealt with the spiritual or mystical interpretation of the text. Tyndale accepted the literal sense of Scripture.12

This was absolutely decisive in determining the course of his life. Once he had made this decision about the authority and interpretation of the Bible, the die was cast. There could be no compromise. His break with Rome was inevitable. His death was certain.

Luther’s influence on Tyndales theology was significant indeed. Perhaps at Cambridge he had received his first exposure to Lutheranism. Certainly his stay in Wittenberg would have provided him many opportunities for direct contact with Luther and his doctrine. Luther’s influence is evident in Tyndales teaching of justification by faith alone and of the eucharist as a memorial— not a sacrifice. His Brief Declaration (1533) clearly presents his position.

More recent research, seeking to trace the origins of Puritan thought and theory, has led some scholars back to William Tyndale “in whose writings they found the germ of ideas which would later form the basis of Puritan theology.”13

While opinions vary on the quality of Tyndales theology, he was an important leader among those who shaped the thinking of the English Reformation.

The Political and Social Conscience

Though Tyndales primary interests were in the realm of Bible translation and church reformation, by the nature of his times he was compelled to express his position on the great political and social issues of his day.

Were the reformers actually responsible for the unrest that was undermining the secular authorities in Europe, as was charged by church leaders? Tyndale answered this accusation in 1528 in The Obedience of a Christian Man. Here he argued that the doctrine of the reformers did not condone political unrest, but rather called for obedience to civil authorities, except where obedience to God is concerned. He maintained that the unrest and evils could actually be traced to the Roman church.

Two years later, in The Practice of Prelates, he explored in depth the relation of the church and state, an issue created by Henry VIII’s determination to pursue the annulment of his marriage to Catherine. Here he also addressed various social issues, each from a strong biblical perspective such as the importance of vocation, the relationship between servant and master, the role of landlords and the problem of riches.

Through his writings Tyndale engaged his culture and addressed the pressing evils from a Christian perspective.

A Man for Our Times

Like Abel of old, through Tyndales obedience, scholarship, character and sacrifice, “though he is dead, he still speaks” (Heb. 11:4).

Tyndale was a biblicist. In matters of faith and practice the Scriptures were his first and final authority. His personal faith rested entirely upon the Word of God. It was his faith in the power of the teachings of the Bible to regenerate sinners, reform the church and transform society that nurtured his passion and motivated his life. Today, when philosophy, psychology and sociology seem to dominate, we need to catch again his heartbeat and settled conviction for the trustworthiness, authority and sufficiency of Scripture.

He was also a student and scholar. God used his years of diligent study, careful research, insightful reflection, critical and constructive writing to further the work of God’s kingdom. Today Tyndale stands as a model for Christians, young and old, of discipline, excellence, integrity and courage, when mediocrity is too often the standard.

He was a man of virtuous character. The case can be made that the closer his opponents came to know him, the deeper their respect grew for his character. Even the procurator-general spoke of him as “learned, godly and good.” At a time when education and giftedness get top grades, we need once again to restore character, as seen in Tyndale, to its priority.

He was persecuted and martyred. He started well, he ran well and he finished well. He was faithful unto death. What he stood for incited fierce opposition and intense resistance, but he stood! Today we seem to have enshrined, as our fourth inalienable right, the right to be free from suffering, conflict, opposition and pain. Tyndale’s life declares again that such circumstances are not only part of our calling, but often the crucible that serves to refine and release our distinctive gifts.

And finally, Tyndale’s story also reminds us that Christians who set no limits on their dedication can have massive, positive influence on the powerful forces in control of societies. This is seen in the fact that Tyndale, who was once seen as the public’s enemy, is today heralded as one of its greatest benefactors, and that the Bible in English is a recognized bestseller every year.14

And yet the Tyndale tale is not an isolated story. He was one of a mighty army of spiritual giants who participated in the remarkable drama of how we got our Bible. His is only one frame, especially enlarged in this prologue to commemorate the name change of Ontario Bible College and Ontario Theological Seminary to Tyndale College & Seminary, and to introduce him to a generation that needs to meet him and know him. May his life leave its mark on each of our students, staff and faculty. May we leave his mark on our generation.

The chapters that follow are devoted to the larger picture, stage by stage, of how we got this wonderful treasure we call the Bible.

Bibliography

Curtis, A. K. “William Tyndale.” Christian History, Vol. VI, No.4, Issue 16, pp. 2-35.

Daniell, David. William Tyndale, A Biography. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994.

Douglas, J. D. (ed.). The New International Dictionary of the Christian Church. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1974.

Galli, Mark (ed.). “How We Got Our Bible.” Christian History, Vol. XIII, No.3, Issue 43, pp. 2-4l.

Tenney, Merrill C. The Zondervan Pictorial Encyclopedia of the Bible. 5 Vols. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1975.

Williams, C. H. William Tyndale. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd., 1969.

1 Brian Edwards, “Tyndale’s Betrayal and Death,” Church History, Volume VI, No.4, Issue 16, p. 15.

2 David Daniell, William Tyndale, A Biography (Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1994), p. 100.

3 Ibid., p. 376.

4 Ibid., p. 374.

5 In this summary of Tyndale’s life and times, arrest and trial, I am indebted to Tony Lane, professor of Bible at London Bible College, London, England, in “A Man For All People: Introducing William Tyndale,” Church History, Volume VI, No.4, Issue 16, pp.6-9, and Brian Edwards, minister in Surrey, England, in “Tyndale’s Betrayal and Death,” Church History, Volume VT, No. 4, Issue 16, pp. 12-15.

6 C. H. Williams, William Tyndale (London: Thomas Nelson & Sons Ltd., 1969), p. 80.

7 Ibid., pp. 81, 82.

8 Ibid, p. 84.

9 Ibid, p. 92.

10 Ibid, p. 93.

11 Ibid, p. 94.

12 Ibid, p. 127.

13 Ibid, p. 130.

14 A. K. Curtis, “From The Publisher,” Church History, Volume VI, No.4, Issue 16, p. 2.

Related Topics: Bibliology (The Written Word), Character Study, History

Introduction

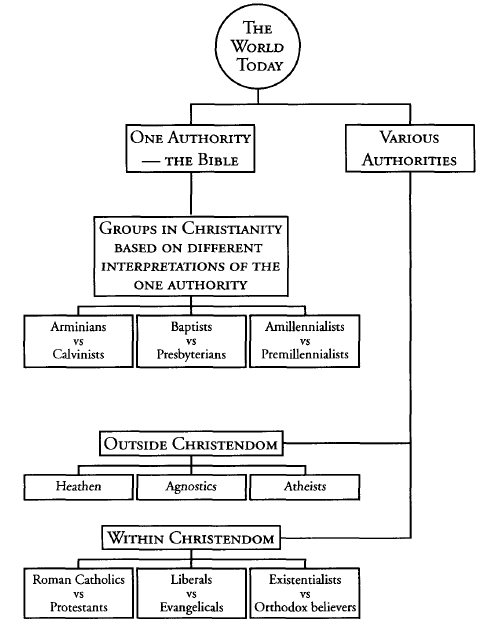

Related MediaA curious Hindu lady, sitting with us in the living room of a mutual friend, asked, “Isn’t the Bible just one among many sacred books in the world today?” After a home Bible study class, a deeply concerned Dallas executive asked, “Why do you believe the Bible?” A rather skeptical young woman at The University of Texas in Austin challenged me during an evening rap session with the question, “How do you know the Bible is really true?” These are questions that cannot be avoided. They deserve honest answers. But what are the answers?

It must be acknowledged, of course, that each of the eleven living world religions has a definite set of documents that is regarded as conveying unique divine truth needed for man’s salvation. The Qur’an of the Muslims and the Vedas of the Hindus both have a theory of verbal inspiration and literal infallibility. The sacred book of each of these religions claims to be pre-eminent. Shintoism’s Ko-ji-ki says, “There is none among the writings in the world so noble and so important as this classic.”

For a moment this seems to settle the point. The Bible is simply one among many sacred books. Yet that is not so. It stands apart from every other book. It is unique and its uniqueness lies in four areas.

It is unique in its moral and ethical standards. The morality and ethics of the Bible are far superior to those of any other sacred book. The “god” of the Qur’an is a “god who deceives people.” Their “heaven” is a place of sensual living: eating, drinking and maidens. Why is this significant? Such concepts reflect the base nature of humanity and human instincts. On the other hand, only too well we know that the holiness, justice and love of the God of the Bible, as well as the total absence of the sensual in God’s heaven, reflect concepts that are very foreign to our nature.

Add to this the uniqueness of the message of salvation the Bible proclaims to mankind. A Hindu may choose to pursue one of three ways of works to obtain salvation. A Buddhist is a lamp unto oneself and seeks for salvation through works. A Muslim must obey the “Five Pillars” of Islam to reach Paradise. And so it is with the religions of the world. The salvation of every individual rests either partially or totally with that person. Salvation is a process dependent upon the works of the individual. Not so in the Bible. Salvation is an act of God apart from our own works. Humans are totally lost, incapable of doing anything toward our salvation. We are entirely shut up to the grace of God. Unparalleled in all religious literature are these majestic words:

For by grace are ye saved through faith: and that not of yourselves, it is the gift of God: Not of works, lest any man should boast. (Eph. 2:8, 9)

But we have only begun. For many people the most persuasive fact pointing to the uniqueness of the Bible is that the Bible alone places upon itself a test. According to Deuteronomy 18:20-22, that test is the accurate fulfillment of prophecy:

But the prophet who shall speak a word presumptuously in My name which I have not commanded him to speak, or which he shall speak in the name of other gods, that prophet shall die.

And you may say in your heart, “How shall we know the word which the Lord has not spoken?”

When a prophet speaks in the name of the Lord, if that thing does not come about or come true, that is the thing which the Lord has not spoken. The prophet has spoken it presumptuously; you shall not be afraid of him.

It is in fulfillment of a prophetic utterance that the truthfulness of the prophet is affirmed.

Philip Mauro observed the significance of this test a number of years ago when, in the introduction to John Urquhart s The Wonders of Prophecy, he said

Let it be remembered that one of the most striking characteristics of the Bible, distinguishing it radically from all other books either ancient or modern, is that it contains in every part, from the third chapter of Genesis to the last of Revelation, predictions in plain language of events that were to take place in the history of mankind on earth.

Let it be remembered too, that the prophecies of the Bible are not confined to small, local affairs, but have for their subjects the most important countries of the world, the most famous nations and empires, the greatest cities.

Had history falsified those prophecies, or any of them, the enemies of the Bible would have put the facts in evidence. Stupendous efforts have been made to prove error in statements of the Bible, whether in regard to facts of nature or facts of history. But here is a field—prophecy—which is both long and wide, and abounds in statements on many subjects.

A field in which, if the statements had been those of men, would contain as many errors as predictions; and yet the enemies of the Bible do not attempt to impeach it for false prophecies.*

Have you ever heard the veracity of the Bible challenged on the grounds of false prophecy? Yet that is the test the Bible places upon itself. No other sacred book dares to subject itself to such a potentially dangerous test.

But to leave the question at this point is to offer an incomplete answer.

The distinctiveness of the Bible rests not only upon its moral and ethical standards, its message of salvation, its test of fulfilled prophecy, but also on the nature and extent of its claim for itself.

It claims to be a direct revelation from God! True, other books claim verbal inspiration, infallibility and divine authority. But no other book makes the kind of claim the Bible makes for itself. Its claim is not based upon a single proof text, nor upon a creedal statement of a church council. It permeates every page of Scripture. No other book has that kind of evidence to support its claim. In the pages that follow, witnesses will be called from six major areas to support its claim.

Among the sacred books of the world, the Bible stands absolutely unique.

A defence of the uniqueness of the Bible, however, only proves that the Bible is unique. It proves nothing more. To answer the challenges raised against its claim for itself and our claims for it, more information, much more information, is needed. It is to meet this need that this book is offered both to the Christian and non-Christian world.

It is my personal conviction that nothing will prepare a person more for the defence of the Bible than a clear understanding of the historical process whereby the Bible came to us. Hopefully, the pages that follow will equip each of us to be more effective defenders of our faith.

* John Urquhart, The Wonders of Prophecy (Harrisburg, PA: Christian Publications, Inc., 1925), viii, ix.

An Overview of the Process: How We Got Our Bible

Related Topics: Bibliology (The Written Word)

Part II: INSPIRATION — Chapter Three: A Second Encounter

Related Media|

Preparing the Way

|

For several years now I have considered doctrinal discipleship classes to be the most significant part of my ministry. With groups of four to seven men or women, I meet weekly for an hour of fellowship in prayer and study. In these small groups I have found a quality of fellowship that has met many deep personal needs. From these groups has emerged a handful of men and women who are marked for spiritual leadership. I wish I had known enough to launch this program twenty years earlier!

The pilot group of this program was one of the most exciting foursome of men I have ever had the privilege of knowing. One was a professional football player with the Cowboys, two were in real estate, and the fourth was a partner in a growing business. Two were married, two were single. All four were relatively young Christians, extremely sharp intellectually and aggressive witnesses for Jesus Christ. It was nothing short of miraculous how God brought the group together—and kept us together.

For more than a year we met on Friday mornings from seven A.M. to nine A.M. This became the highlight of the week for each of us. Although we were different in a dozen ways, we each had a consuming desire to know the Lord, learn the Bible and serve our God. It was a period of such growth in each of our lives that we have been marked for life. We will never recover.

Facing these men for the first month was like stepping before a firing squad. These four sessions were devoted to a study of the doctrine of the Bible. We began by establishing the Bible’s claim for itself—it is a revelation from God. This claim, as we now know, is well supported by the Bible’s prophecy, unity and accuracy.

Then the big guns came out! Rather than solving a problem, I had actually stirred a hornet’s nest. If I were to sort out their questions and simplify the issue, I think it would be stated this way: How can you be sure that what the authors recorded in their writings was an accurate record of what God had revealed to them?

That is a fair question. It also is an important one.

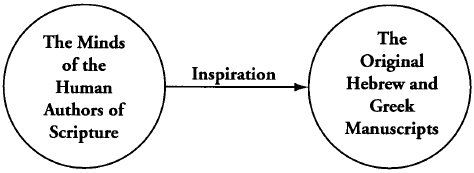

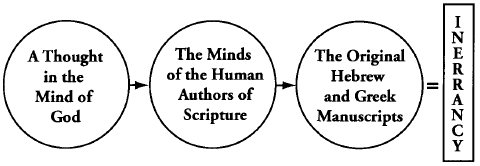

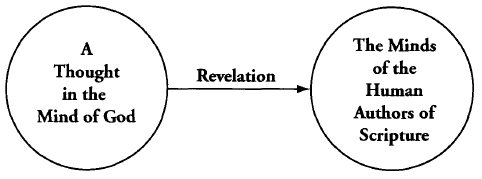

The answer is wrapped up in the doctrine of inspiration. This is what bridges the gap between the thoughts in the minds of the human authors and the writing of these thoughts in the original Greek and Hebrew manuscripts.

To answer the questions of my “fierce foursome” an entire session was devoted to a study of inspiration. It is the substance of that class that makes up the content of this chapter. In grappling with this subject our goal is to gain a firm grasp on the meaning of inspiration, its supporting evidence and its extent.

In probing the doctrine of inspiration in this chapter we must first establish a definition, then support it and finally consider the extent to which the Scriptures are inspired.

Today we use the word inspiration in a variety of ways. We speak of a person being “inspired” by a dynamic sermon, a moving symphony or a soul-stirring book. A select number of hymns are considered “inspirational.” Certain personalities are “inspiring.” Handel is said to have been “inspired” when he composed The Messiah. Current usage suggests some outside influence arousing within us extraordinary thoughts, feelings or actions. This is not the biblical meaning of inspiration.

I. An Important Correction

In the New Testament the word occurs only once. “All Scripture is inspired by God ...” (2 Tim. 3:16) Our English phrase in the Authorized Version, “inspiration of God,” was inherited from Tyndale, whose 1525 edition was the first printed English New Testament. So excellent was his work that most English versions since that time are indebted to it. However, in this case the translation is misleading and does not reflect accurately the original Greek word in 2 Timothy 3:16.

The English word “inspiration” suggests “inbreathing” or “God breathing into.” The term Paul uses speaks nothing of inspiration, but only of aspiration. Literally, the Greek compound word means “God-breathed.” God did not “breathe into” the Scripture nor did He “breathe into” the authors. Our text says He “breathed” the Scripture. Warfield is accurate and helpful when he says,

In a word, what is declared by this fundamental passage is simply that all the Scriptures are a divine product, without any indication of how God has operated in producing them.1

First of all, it is obvious that it is the Scriptures that are inspired, not the authors. Have you ever heard someone speak of the “inspired apostle” or the “inspired writers”? Do you see the error here? It is not Paul but Paul’s writings that are inspired. God so controlled the writer that what he wrote was actually “God-breathed.” God breathed His Word through them.

Does this suppose that the authors were merely passive robots recording what God dictated? By no means. The individuality of each writer is seen in his peculiar style and vocabulary. In his Gospel, Luke the physician (Col. 4:14) uses a profusion of medical terms that are absent from the other three Gospels. There is a distinctive style in Paul’s epistles that sets his letters apart from Peter’s and Johns.

Can anything be inferred concerning the accuracy of the record from the fact that it is “God-breathed”? Certainly. If it is “God-breathed” it is surely accurate and without error. Because He is the “only true God” (John 17:3), the God who cannot lie (Heb. 6:18), it is inconceivable that He should “breathe” something not true. This deduction must be examined more fully, but we shall reserve that for a later chapter. Yet it does raise a question that cannot be put off.

Isn’t it impossible that an inerrant Scripture could come to us through sinful men? Not at all. As in the incarnation of the living Word, Jesus Christ, so in the inspiration of the written Word, the Bible, there is a unique blending of the human and divine. In the incarnation the Son of God came into the world through Mary, but was a “holy thing” (Luke 1:35) wholly untainted by the sinful nature of His mother. As He who is absolutely holy, pure and perfect came through one who was unholy, fallen and imperfect, so the Word of God, which is holy and true, came through fallen and sinful men.

Although in both cases the channels were imperfect, in the providence of God the products were unaffected.

It hardly needs to be mentioned that inspiration applies only to the recording of God’s revelation in the original manuscripts. This is obvious.

Now put these pieces together in your definition of inspiration. In substance it will conform to that of Dr. C. C. Ryrie who says,

Biblical inspiration may be defined as God’s superintending human authors so that, using their own individual personalities, they composed and recorded without error His revelation to man in the words of the original autographs.2

From B. B. Warfield came a similar definition when he said, “Inspiration is the supernatural influence exerted on the sacred writers by the Spirit of God, by virtue of which their writings are given Divine trustworthiness.”3

Project Number 1

- List the essential points that must be included in any definition of inspiration.

- What is the basis for such a doctrine? What does it rest on?

II. More Evidences

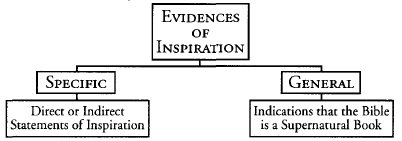

The evidences in support of the biblical doctrine of inspiration fall into two classifications: specific and general.

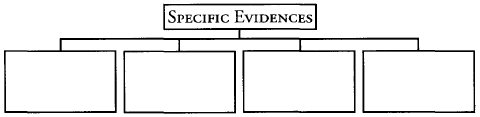

A. The Specific Evidences

Many direct and indirect statements in the Bible regarding its inspiration may be marshalled as specific supporting evidence. As an aid to memory it will be helpful to organize them into four classes.

1. The testimony of Paul

All Scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness. (2 Tim. 3:16)

This is the primary and central text on inspiration. It makes three major contributions to our subject.

It specifies the value of Scripture. It is useful for teaching doctrine, for reproving false teachers, for correcting those misled by heresy and for instructing the people of God in a righteous walk. It is “all” useful. Have you ever wondered about the profit of those chapters of genealogies or those lists of kings?

Mr. Newman, an agnostic, once challenged J. N. Darby on this very point. He quoted, “When you come, bring the cloak which I left in Troas with Carpus, and the books, especially the parchments” (2 Tim. 4:13). Then he asked, “What relevance is there in this verse?” At the time Darby was living frugally in Ireland as a missionary and told Newman it was this very verse that had kept him from selling his small library when he went out to Ireland as a missionary. You can count on it. Everything God says in His Word is profitable!

More than that, it declares the ultimate origin of “all Scripture.” It is God-breathed! That which is the product of God is described here as “Scripture.” This phrase includes all the books of the Old Testament canon, which were by that time gathered into an authoritative corpus of literature. It is to this collection that Paul refers when he speaks in verse 15 of the “Holy Scriptures” that Timothy had been taught from childhood. The word “Scripture” is a technical term for authoritative divine writings. It also occurred “currently in Philo and Josephus to designate that body of authoritative books which constituted the Jewish ‘Law’.”4

The “Scripture” of verse 16 includes not only the books of the Old Testament, but also those of the New Testament, some of which were still unwritten! The word Paul uses for “Scripture” had become a technical word for the New Testament books too. Paul uses it in 1 Timothy 5:18, where he refers to an Old Testament quotation from Deuteronomy 25:4 and a New Testament quotation from Matthew 10:10 as “Scripture.” Peter refers to Paul’s letters as “Scripture” in 2 Peter 3:16. In 2 Timothy 3:16, Paul does not define the limits of “Scripture” but asserts that everything that is “Scripture” is God-breathed.

The third contribution of our text is by way of implication. When he says all Scripture is God-breathed, Paul implies something about the nature of Scripture. It is divine, true and authoritative.

2. The testimony of Peter

But know this first of all, that no prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation, for no prophecy was ever made by an act of human will, but men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God. (2 Pet. 1:20, 21)

This coincides exactly with the testimony of Paul. Peter is particularly occupied with one segment of Scripture—the prophetic Scriptures. However, what is true of them is true of all Scriptures. What is that? Peter gives it negatively, then positively.

It was not “by an act of human will.” The Scriptures did not originate with humans! In the entire context Peter is speaking of authentication, not interpretation, and here states that the authors did not make up what they wrote. This is the truth conveyed in the Authorized Version’s troublesome phrase of verse 20, “no prophecy of Scripture is of any private interpretation.” That is, it did not originate with the prophet himself, nor is it the product of his own investigation.5

Positively, it came as “men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God.” Here the human and divine elements in inspiration are again affirmed. “Men spoke.” These were the human authors. But they did not speak on their own initiative, of their own thoughts, for their own purposes. Calvin says, “They did not blab their inventions of their own accord or according to their own judgments.” They spoke as they were “moved by the Holy Spirit.” Peter uses an intriguing metaphor here. The Greek verb translated “moved” is used in Acts 27:15, 17 where a ship is “carried along” by the wind. Submissive to the Holy Spirit then, these holy men of old were “carried along,” “borne along,” in the direction He wished to take them.

In one sense this text coincides exactly with the testimony of Paul. It asserts the divine origin of the Scriptures. It emphatically denies any human origin. However, in another sense it actually goes further than Paul’s testimony.

Peter includes the human element. “Men spoke; God spoke. Any proper doctrine of Scripture will not neglect either part of this truth.”6 The major contribution of this text is in its explanation of how men recorded the truth of God’s revelation. They were moved, borne along, carried along. It is in this phrase that we see the superintending work of God in inspiration. It also identifies the specific, divine agent of inspiration to be the Holy Spirit.

3. The testimony of Christ

Our Lord believed the entire Old Testament was inspired. He said,

Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish, but to fulfill. For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass away from the Law, until all is accomplished. (Matt. 5:17, 18)

That would be so only if all the books of the law were inspired of God. Also, He explicitly testified that David was speaking by the Holy Spirit when Christ said:

He said to them, “Then how does David in the Spirit call Him ‘Lord’ ...?” (Matt. 22:43)

In John 10:35 He bore testimony to the divine nature of the Old Testament when He said, “the Scripture cannot be broken.” Further witness from our Lord can be seen in Matthew 12:3, 5; 19:4 and Mark 12:24.

4. The testimony of others

Scores of witnesses could be called to the stand here. Let me mention only a few. David claims it for himself in 2 Samuel 23:1 (cf. Mark 12:36). Nehemiah recognizes that the prophets spoke by the Holy Spirit (Neh. 9:3, 30) and that the law given by Moses was God’s law (Neh. 10:29). Luke says it was the Holy Spirit who was speaking through Isaiah (Acts 28:25). Paul virtually claims inspiration for himself when he says, “the things I write unto you are the commandments of the Lord” (1 Cor. 14:37). Again, Paul considered Luke’s Gospel to be “Scripture” and places it on equal footing with the Old Testament Scripture (1 Tim. 5:18, Luke 10:7). Peter designates Paul’s epistles as “Scripture” also (2 Pet. 3:16).

Project Number 2

Complete the following chart on the specific evidence of inspiration.

This multitude of direct and indirect statements constitutes the specific supporting evidences for the inspiration of the Bible. But there is also an impressive array of general evidences.

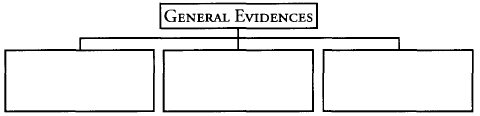

B. The General Evidences

All indications apart from specific statements that the Bible is a supernatural book constitute the general supporting evidences of inspiration.

Of course, inspiration cannot be proved. As it is impossible to prove the existence of God, so it is impossible to prove the inspiration of Scripture. Obviously it claims to be inspired. The myriad direct and indirect statements establish that point. But anyone can make such claims. What evidence is there in support of this claim?

In the previous chapter we considered three evidences of revelation: fulfilled prophecy, the unity of the Bible, and its historical and scientific accuracy. These point to the supernatural original of the Bible and therefore indicate the superintending work of God and the Holy Spirit in inspiration as well.

But that is not all. There are indications from three other major areas that this is a supernatural book, inspired by God. These are the general evidences.

1. The testimony of history

From the pages of human history come statements of philosophers, scholars, students, theologians, politicians, artists and historians to the effect that this is a unique and supernatural book. From its unique and supernatural nature, we can infer its authority.

Josephus, the unbelieving Jewish historian of the first century, spoke of his people’s attitude toward the Bible when he said,

How firmly we have given credit to these books of our own nation is evident in what we do; for during so many ages as have already passed no one hath been so bold as either to add anything to them, to take anything from them, or to make any change; but it is become natural to all Jews, immediately and from their very birth, to esteem these books to contain divine doctrine, and to persist in them, and if occasion be, willing to the for them.7

Robert E. Lee, American soldier and educator said, “The Bible is a book in comparison with which all others in my eyes are of minor importance, and which in all my perplexities and distresses has never failed to give me light and strength.”

William E. Gladstone, prime minister of England, said, “The Bible is stamped with specialty of origin and an immeasurable distance separates it from all competitors.”

Mathematician and philosopher Sir Isaac Newton said, “We account the Scriptures of God to be the most sublime philosophy. There are more sure marks of authority in the Bible than in any secular history whatever.”

“The Bible is the best book in the world,” said John Adams, second president of the United States.

The American orator and statesman Daniel Webster once prophesied, “If we abide by the principles taught in the Bible, our country will go on prospering; but if we in our prosperity neglect its instruction and authority, no man can tell how sudden a catastrophe may overwhelm us and bury all our glory in profound obscurity.”

Sir Walter Scott, when he was dying, asked his friend Lockhart to read to him. Looking over the 20,000 books in his costly library, Lockhart asked, “Which book would you like?” “Need you ask,” said Scott, “There is but One.”

The testimony of history from every age and every field is that this is a supernatural book.

2. The testimony of its influence

John Richard Green begins his second volume of A Short History of the English People with these words:

No greater moral change ever passed over a nation than passed over England during the years which parted the middle of the reign of Elizabeth from the meeting of the Long Parliament. England became the people of the book, and that Book was the Bible.

Under the influence of the Bible, women have been liberated from their status of inferiority, hospitals have been erected for the care of the sick, a reverence for human life has developed, the significance of marriage and the role of the partners has been revolutionized, and the institution of slavery has collapsed.

J. B. Phillips, well-known translator of the Bible, shares this thrilling story:

Some years before the publication of the New English Bible, I was invited by the BBC to discuss the problems of translation with Dr. E. V. Rieu, who had himself recently produced a translation of the four Gospels for Penguin Classics. Towards the end of the discussion Dr. Rieu was asked about his general approach to the task, and his reply was this: “My personal reason for doing this was my own intense desire to satisfy myself as to the authenticity and the spiritual content of the Gospels. And, if I received any new light by an intensive study of the Greek originals, to pass it on to others. I approached them in the same spirit as I would have approached them had they been presented to me as recently discovered Greek manuscripts.”

A few minutes later I asked him, “Did you get the feeling that the whole material is extraordinarily alive? ... I got the feeling that the whole thing was alive even while one was translating. Even though one did a dozen versions of a particular passage, it was still living. Did you get that feeling?”

Dr. Rieu replied, “I got the deepest feeling that I possibly could have expected. It changed me; my work changed me. And I came to the conclusion that these words bear the seal of the Son of Man and God. And they’re the Magna Carta of the human spirit.”

I found it particularly thrilling to hear a man who is a scholar of the first rank as well as a man of wisdom and experience openly admitting that these words written long ago were alive with power. They bore to him, as to me, the ring of truth.8

When an atheist challenged H. A. Ironside to debate the existence of God, he accepted on one condition. The atheist was to bring ten men with him who would testify as to how their lives had been enriched by the teaching of atheism and Ironside would bring one hundred. The atheist never did show up.

Dr. A. T. Pierson wrote in the nineteenth century:

The Bible is the greatest traveller in the world. It penetrates to every country in the world, civilized and uncivilized. It is seen in the royal palace and in the humble cottage. It is the friend of emperors and beggars. It is read by the light of the dim candle and amid Arctic snows. It is read in the glare of the equatorial sun. It is read in city and country, amid the crowds and in solitude. Wherever its message is received it frees the mind from bondage and fills the heart with gladness.9

The influence of the Scriptures supports the claim that it is God-breathed.

3. The testimony of its preservation

In tribute to the indestructibleness of the Bible, A. Z. Conrad has written:

Century follows century—there it stands.

Empires rise and fall and are forgotten—there it stands.

Dynasty succeeds dynasty—there it stands.

Kings are crowned and uncrowned—there it stands.

Despised and torn to pieces—there it stands.

Storms of hate swirl about it—there it stands.

Atheists rail against it—there it stands.

Profane, prayerless punsters caricature it—there it stands.

Unbelief abandons it—there it stands.

Thunderbolts of wrath smite it—there it stands.

The flames are kindled about it—there it stands.

The arrows of hate are discharged against it—there it stands.

Fogs of sophistry conceal it temporarily—there it stands.

Infidels predict its abandonment—there it stands.

The tooth of time gnaws but makes no dent—there it stands.

An anvil that has broken a million hammers—there it stands. 10

In spite of the passing of time, the Bible still stands. We used to say that one out of every twenty books will last seven years. Now it is probably less than that. School textbooks are quickly outdated. What book 500 years old is read by masses of common people?

In spite of the persecution of its enemies, the Bible still stands.

Voltaire said that in a hundred years the Bible would not be read. One hundred years later a press was printing Bibles in his very home in France. Thomas Paine once said, “In five years from now there will not be a Bible in America. I have gone through the Bible with an axe and cut down all the trees.” Today it still stands. Dr. Torrey writes:

This book has always been hated. No sooner was it given to the world than it met the hatred of men, and they tried to stamp it out. Celsus tried it by the brilliancy of his genius; Porphyry by the depth of his philosophy, but they failed. Lucian directed against it the shafts of his ridicule; Diocletian the power of the Roman Empire, but they failed. Edicts backed by all the power of the empire were issued that every Bible should be burned, and that everyone who had a Bible should be put to death. For eighteen centuries every engine of destruction that human science, philosophy, wit, reasoning or brutality could bring to bear against that book to stamp it out of the world has been used, but it has a mightier hold on the world today than ever before.11

Someone has said the Bible is like the Englishman’s wall that was built three feet high and four feet wide. When asked why, he said, “I built it that way so that if the storms should come and blow it over, it will be higher afterwards than before.” The Bible stands higher today than ever!

“After forty-five years of scholarly research in biblical textual studies and language study,” said the late Robert Dick Wilson, Ph.D., professor of Semitic Philology at Princeton Theological Seminary, “I have come now to the conviction that no man knows enough to assail the truthfulness of the Old Testament. Wherever there is sufficient documentary evidence to make an investigation, the statements of the Bible, in the original text, have stood the test.”12

Project Number 3

1. Complete the following chart on the general evidences in support of the inspiration of the Bible.

2. Discuss the assertion that “Many books influence life. Only the Bible transforms life.”

In a survey reported in Christianity Today (Sept. 11, 1970), the question was asked, “Do you believe the Bible is the inspired Word of God?” This question received a negative answer from 87 percent of Methodists who responded, 88 percent of Presbyterians, 95 percent of Episcopalians, 67 percent of American Baptists and 77 percent of American Lutherans. Karl Barth is clear and precise in rejecting the orthodox doctrine of inspiration, which he calls “the lame hypothesis of the 17th Century doctrine of inspiration.”13

And yet there are six major evidences that have been brought forward in defence of its claims that the Bible is a supernatural book. They are:

- fulfilled prophecy

- the unity of the Scriptures

- the historical and scientific accuracy

- the testimony of history

- the astounding influence of the Bible

- its amazing preservation

Every Christian should memorize these six evidences and be prepared to illustrate each one. Although they are not conclusive, they cannot be ignored! There is extensive evidence to support the claim of inspiration.

Yet, it is one thing to acknowledge that the Bible is a book inspired by God, but quite another thing to say all the Bible, every part of the Bible, is God-breathed.

We may be prepared to admit the first, but the second—that causes many to choke just a little. Here is a fair question, To what extent are the Scriptures actually inspired of God?

III. A Matter of Controversy

There are several schools of thought even among evangelicals on the extent of inspiration.

A. The Varying Degree View of Inspiration

Some, for example, believe there are varying degrees of inspiration in the Bible. Who better to represent this school than C. S. Lewis, who wrote: “All Holy Scripture is in some sense—though not all parts of it in the same sense—the word of God.14

He explained what he meant when he said:

Something originally merely natural—the kind of myth that is found among most nations—will have been raised by God above itself, qualified by Him and compelled by Him to serve purposes which of itself it would not have served.15

Obviously, then, although he has a high view of the text, Lewis sees varying degrees of inspiration, especially in the Old Testament Scriptures.

It is this view that may say the story of the flood was originally of Mesopotamia, but was elevated by God above itself and incorporated into the Bible to teach a lesson.

B. The Conceptual View of Inspiration

Others maintain that only the concepts of the Bible are inspired. J. B. Phillips speaks for this school when he says: “Any man who has sense as well as faith is bound to conclude that it is the truths which are inspired and not the words, which are merely the vehicles of truth.16

He rejects any idea that the actual words of Scripture are inspired. Only the ideas or concepts transmitted to the minds of the authors are considered as God-breathed.

However there is a fatal weakness here. Concepts must be communicated through words. There is no other way. For God’s concepts to be communicated to the authors and for these men to communicate those thoughts to us, words had to be used. For that concept to be conveyed accurately the words must be inspired. Otherwise there is no guarantee that the thought has been precisely expressed.

C. The Partial View of Inspiration

It is increasingly popular today to say that the trustworthiness of the Scriptures applies only to matters of faith and doctrine, not history—in matters of salvation, Scripture is inspired; in matters of history or science, it is not. That is, inspiration is restricted to those parts of Scripture that are doctrinal.

But 2 Timothy 3:16 says, “All Scripture is God-breathed.” Not part of it, but all of it. Furthermore, the line between doctrine and history can be very subjective and arbitrary. Who can draw such a line? Where is it to be drawn in Genesis 3?

D. The Verbal Plenary View of Inspiration

It seems difficult to avoid the fact of the verbal plenary inspiration of Scripture. Verbal inspiration is the inspiration of the words themselves (not the ideas or truths) in the original. Paul rests his argument of Galatians 3:16 upon a doctrine of verbal inspiration. Here the difference between a singular (“seed”) and plural (“seeds”) in Genesis 12:7; 13:15; and 17:7 is the basis of Paul’s argument. The very letters of a word are reliable, therefore inspired.

Does not Matthew 5:18 imply that our Lord believed in verbal inspiration? In speaking of the sacred writings of the Jews, the Old Testament, He says:

For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass away from the Law, until all is accomplished.

The “jot” of the Authorized Version is the smallest letter of the Hebrew alphabet—yodh (י). It is similar to our apostrophe. Probably the “tittle” is the very small horn on the Hebrew letter daleth (ד) which distinguishes it from the letter resh (ר). Speaking on this verse, R. Laird Harris observes: “He says very positively that this Book is perfect to smallest detail. It is not merely verbal inspiration that teaches here, but inspiration of the very letter!”17

In the parallel passage, Luke 16:17, our Lord says, “But it is easier for heaven and earth to pass away than for one stroke of a letter of the Law to fail.”

Note also the Lord’s comment about His own words in Luke 21:33: “Heaven and earth will pass away, but My words will not pass away.

In Matthew 22:43, the Lords entire argument revolves around the single word “My.” David spoke of Messiah as “My Lord” (emphasis added). That was a confession to His deity. Observe especially that the “my” in the original Hebrew text was one letter only—a yodh. This is an amazing corroboration of Matthew 5:18. His entire defence of His deity rests upon the reliability of one letter, the smallest of all Hebrew letters.

The main objection to verbal inspiration is that it leads to a very wooden view of the Bible. Some say it destroys the humanity of the authors if they passively recorded, as secretaries, what God dictated. Obviously a dictation view of inspiration is untenable. The styles and vocabularies of the writers differ greatly according to their background and training. They certainly were not passively recording what was being dictated to them.

But verbal inspiration does not require a dictation view. It was achieved by the Holy Spirit who superintended the human authors as they chose words from their vocabulary.

Philosophically, verbal inspiration is a logical necessity because the only way to accurately communicate concepts or truths is by words. As this is God’s purpose in revelation and inspiration, it demands His direct personal involvement in the words used. Our Lord testifies to this. The apostles assume it.

The correct view of inspiration includes not only verbal but also plenary inspiration. Plenary inspiration speaks of the inspiration of the entire Bible, of every word in the Bible, not just certain parts. There are no degrees of inspiration. “All Scripture is God-breathed” (2 Tim. 3:16).

Clark Pinnock expresses it well when he says,

Inspiration guarantees all that Scripture teaches. It is a seamless garment, an indivisible body. Jesus Christ accepted no dichotomy or dualism in Scripture between true and false, revealed and unrevealed matters. His attitude was one of total trust. For example, He obviously regarded the entire Old Testament history as factually correct; the Gospels record at least twenty allusions to incidents from the creation of Adam to Daniel’s prophecies and Jonah’s preaching. He regarded the entire Scripture as trustworthy, the commonplace as well as the extraordinary.18

The same author quotes from a sermon delivered in 1858, by J. C. Ryle on 2 Corinthians 2:17. Ryle said,

We corrupt the Word of God most dangerously, when we throw any doubt on the plenary inspiration of any part of Holy Scripture. This is not merely corrupting the bucket of living water, which we profess to be presenting to our people, but poisoning the whole well. Once wrong on this point, the whole substance of our religion is in danger. It is a flaw in the foundation. It is a worm at the root of our theology. Once allow the worm to gnaw the root, and we must not be surprised if the branches, the leaves, and the fruit, little by little, decay.

The whole subject of inspiration, I am aware, is surrounded with difficulty. All I would say is, notwithstanding some difficulties which we may not be able now to solve, the only safe and tenable ground to maintain is this—that every chapter, and every verse, and every word in the Bible has been given by inspiration of God. We should never desert a great principle in theology any more than in science, because of apparent difficulties which we are not able at present to remove.19

As “verbal” stands against the conceptual view of inspiration, so “plenary” stands against the partial and varying degree views of inspiration. What is the extent of inspiration? It extends to the very words and to all the words.

Project Number 4

1. Why is the doctrine of inspiration important?

2. What, then, is your answer for my four friends who want to know how we can be sure the Bible contains an accurate record of God’s revelation to man?

A notable New Testament scholar was once approached by an ardent admirer pouring forth his praise. To the scholar he said, “I’ve always wanted to meet a theologian who stands on the Word of God.”

Quietly the reply came back, “Thank you sir, but I do not stand on the Word of God, I stand under it.”

Where else is there to stand if, indeed, it is the revealed inspired Word of God? Do you stand under it in your creed and conduct, your faith and practice?

R. Laird Harris sounds a solemn warning when he says,

In Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, we read that at one point in his journey Pilgrim slept awhile and lost his scroll. Bunyan grippingly pictures the anxiety and trouble that ensued until Pilgrim retraced his steps and found his book. America has lost its belief in and emphasis upon the Bible. There was a time when it was read and taught in our schools. Now more than the most perfunctory reading of it is said to be illegal. It used to be preached, memorized, quoted, studied and believed. Now this is true only in restricted circles. America must return to the Bible. But we shall not return to the Bible as long as it is regarded merely as great literature. It is only when we receive it as Gods holy and infallible Word that it will bring the promised blessing.20

We have now bridged two gigantic gaps in the historical process. The gap from God’s mind to the authors’ minds is spanned by revelation, and the gap from the authors’ minds to the original writings is spanned by inspiration.

These two tremendous truths carry with them two implications of the greatest possible magnitude. One implication set off a very heated controversy (battle!) a few years ago. The other is calculated to shatter many a dream and revolutionize every life. It is to these very implications that we turn in the following two chapters.

Review

Before you move on to chapter four take time to review. It is never time wasted. It will yield rich dividends as you proceed. Turn back to those ten questions that stumped you at the beginning of the chapter. How many can you answer now?

When you have control of the answers for all ten, you are ready for chapter four.

For Further Study

- Trace the history of verbal inspiration through the history of the church.

- Critique fully the opposing views of inspiration: varying degrees, partial, conceptual and dictation.

- In what sense can you say a part of the Scriptures is inspired which was copied by the author from some literature outside the Bible (e.g., Titus 1:12)?

Bibliography

Harris, R. Laird. Inspiration and Canonicity of the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1957.

Pinnock, Clark. Biblical Revelation. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1971.

Ryrie, Charles Caldwell. The Holy Spirit. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1965.

Warfield, Benjamin Breckinridge. The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible. Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1970.

Young, Edward J. Thy Word Is Truth. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1967.

1 B. B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible (Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1970), p. 133.

2 C. C. Ryrie, The Holy Spirit (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1967), p. 33.

3 B. B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible, p. 133.

4 Ibid., p. 133.

5 M. Green, The Second Epistle of Peter and the Epistle of Jude (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1968), p. 90.

6 Ibid., p. 91.

7 Flavius Josephus, “Against Apion” 1, 8. The Works of Flavius Josephus, Trans, by Wm. Whiston (London, Wm. P. Nimm), p. 609.

8 J. B Phillips, The Ring of Truth (New York, NY: The MacMillan Company, 1967), pp. 74, 75.

9 Quoted by A. Naismith, The Veracity and Infallibility of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Gospel Folio Press, n.d.), p. 5.

10 Quoted by Walter B. Knight, Knight’s Illustrations for Today (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1970), p. 22.

11 R. A. Torrey, “Ten Reasons Why I Believe the Bible Is the Word of God,” Our Bible (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, n.d.), p. 123.

12 Quoted by Walter B. Knight, Knight’s Illustrations for Today (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1970), p. 22.

13 Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, G.W. Bromiley and T.F. Torrance (eds.), (Edinburgh, 1936-62), III, Part 1, p. 24.

14 C. S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms (New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc., 1958), p. 19.

15 Ibid., p. 111.

16 J. B. Phillips, The Ring of Truth, pp. 21, 22.

17 R. Laird Harris, Inspiration and Canonicity of the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1969), p. 46.

18 Clark Pinnock, Biblical Revelation (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1971), p. 87.

19 Ibid., p. 88.

20 R. Laird Harris, Inspiration and Canonicity of the Bible, pp. 70, 71.

Related Topics: Bibliology (The Written Word), Inspiration

Part III: INERRANCY — Chapter Four: Completely Trustworthy

Related Media|

Preparing the Way

|

Recently I read of a seminary student who was serving as student pastor of a small church. Expressing the concern of his congregation he asked, “My people ask me, ‘If the Bible says it, can I believe it?’”1

That’s a fair question! It is also a common and critical question. Our answer, “It is completely trustworthy.” That is what we mean by “inerrancy.”

Few subjects are more divisive.

Some people blatantly deny inerrancy. An accepted authority among spiritualists, Dr. Moses Hull, once wrote these outrageous words:

The Bible is, I think, one of the best of the sacred books of the ages. It is supposedly the sacred fountain from which two, if not three, of the greatest religions of the world have flowed... . While the Bible is not the infallible or immaculate book that many have supposed it to be, no one can deny that it is a great book... . Yet it must be confessed that the age of critical analysis of all its sayings and its environments has hardly dawned... . John R. Shannon said to his Denver audience, “We do not believe in the verbal inspiration of the Bible. The dogma that every word of the Bible is supernaturally dictated is false. It ought to be shelved away... . Verbal inspiration is a superstitious theory; it has turned multitudes in disgust from the Bible; it has led thousands into infidelity; it has led to savage theological warfare... . All these facts would show if brought out, that the Bible, like all other books, is exceedingly human in its origin. While the Bible is, none of it infallible, none of it unerring—when rightly interpreted it is, all of it, useful, all of it good.”2

Others quietly ignore it. One large denomination in North America recently chopped the word “inerrant” from its statement of faith. For years many of our most influential evangelical leaders have refused to deny it openly. Rather they have quietly chosen to refuse to affirm it.

“To those in the broader theological community, this seems an irrelevant issue, a carry-over from an antiquarian view of the Bible.”3

To many evangelicals, however, it is extremely important. The argument takes the form of a logical conclusion.

Granted that God did reveal Himself to the human authors and that the human authors, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, did record accurately what was revealed to them, what are the implications for the Scriptures?

Revelation + Inspiration = Inerrancy

If the Bible is a divine revelation that has been God-breathed then, they say, the inerrancy of the Scriptures naturally follows. This is what is to be explored in this chapter.

Inerrancy means different things to different people. Consider, for example, the various evangelical theories on inerrancy as summarized by H. Wayne House in the following chart.

|

Evangelical Theories on Inerrancy4 |

||

|

Position |

Proponent |

Statement of Viewpoint |

|

Complete Inerrancy |

Harold Lindsell Roger Nicole Millard Erickson |

The Bible is fully true in all its teaches or affirms. This extends to the areas of both history and science. It does not hold that the Bible has a primary purpose to present exact information concerning history and science. Therefore the use of popular expressions, approximations and phenomenal language is acknowledged and believed to fulfill the requirement of truthfulness. Apparent discrepancies, therefore, can and must be harmonized. |

|

Limited Inerrancy |

Daniel Fuller Stephen Davis William LaSor |

The Bible is inerrant only in its salvific doctrinal teachings. The Bible is not intended to teach science or history, nor did God reveal matters of history or science to the writers. In these areas the Bible reflects the understanding of its culture and may therefore contain errors. |

|

Inerrancy of Purpose |

Jack Rogers James Orr |

The Bible is without error in accomplishing its primary purpose of bringing people into personal fellowship with Christ. The Scriptures, therefore, are truthful (inerrant) only in that they accomplish their primary purpose, not by being factual or accurate in what they assert. (This view is similar to the Irrelevancy of Inerrancy view.) |

|

The Irrelevancy of Inerrancy |

David Hubbard |

Inerrancy is essentially irrelevant for a variety of reasons: (1) Inerrancy is a negative concept. Our view of Scripture should be positive. (2) Inerrancy is an unbiblical concept. (3) Error in the Scriptures is a spiritual or moral matter, not an intellectual one. (4) Inerrancy focuses our attention on minutiae, rather than on the primary concerns of Scripture. (5) Inerrancy hinders honest evaluation of the Scriptures. (6) Inerrancy creates disunity in the church. (This view is similar to the Inerrancy of Purpose view.) |

Complete inerrancy declares the Scriptures to be completely trustworthy in all they affirm. There is total agreement among advocates of this position in terms of their view of the theological or spiritual message. They may, however, differ in their understanding of the scientific and historical references. In contrast to Lindsell, for example, Nicole regards scientific and historical elements as phenomenal.5 That is,

[T]hey are reported as they appear to the human eye. They are not necessarily exact; rather they are popular descriptions, often involving general references or approximations. Yet they are correct. What they teach is essentially correct in the way they teach it.6

I. A Closer Look

What then do we mean when we speak of the inerrancy of Scripture? We mean it is completely truthful and trustworthy in all of its teachings. Though the expressions may vary, the essence is consistent in a multitude of popular and current statements.