Part IV: AUTHORITY — Chapter Five: A Desperate Dilemma

Related Media|

Preparing the Way

|

“Karen” was one of the loveliest young ladies I have ever met. Although I had heard a great deal about her, our first personal encounter took place in my study several years ago. She had phoned and asked to see me about a personal problem. An hour or two later she appeared at my door—with a girl friend. To my surprise both were carrying Bibles.

I listened as she told me of her recent conversion to Christ. What an amazing story that was. God had invaded her neat and comfortable life. For several years she had lived life to the full. She had tasted the pleasures this old world has to offer and enjoyed them all. Then came her new birth. She was born again into the family of God. She had committed her life to Jesus Christ.

Now she was in a dilemma. Although she was unmarried, she was living with a man who also had recently become a Christian. They loved one another and needed one another.

Her parents were horrified. Her Christian friends were critical. Yet her boyfriend refused to consider a change in their relationship. In the midst of it all she was being torn to pieces.

For almost an hour we sparred. I used every argument I knew, and there are many, in my attempt to persuade her to abandon a lifestyle that was destroying her. It almost seemed, however, that the more I tried to convince her of the error of her way, the more convinced she became of its rightness.

Eventually, about an hour too late, I finally saw the problem at the root of her dilemma. It is one of the most basic and important issues in every life. It is the question of authority.

Every area of every life is touched by this issue. Every struggle is a confrontation with the question of authority. To resolve this conflict is to settle a thousand storms that will rage in every believer’s bosom. It is to this end that our present chapter is dedicated.

The concept of authority is not a popular one today. The world of Woodstock rejects it. The militant revolutionary attacks it. The women’s liberation movement redefines it. The draft dodger defies it. Parents and civil authorities surrender it. And yet, the real question is not, Authority or not authority? but rather What is the authority? Each one has an authority. This dictates the direction of life and determines one’s principles. This is at the root of the dilemma my young friend faced in my office that afternoon. “Karen’s” problem was really one of authority. This is no new problem.

I. A Perennial Problem

It is certainly no overstatement to say, “The problem of authority is the most fundamental problem that the Christian Church ever faces.”1

This is no exaggeration. Any survey of church history will attest to its truthfulness. But why? Why is the issue of authority so central? There are three major reasons.

A. The nature of the message

In contrast to many world religions, which are based upon ideas and principles, Christianity is built upon objective revealed truth. Its message is, “But God demonstrates His own love toward us in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us” (Rom. 5:8).

The promise is eternal life:

And the witness is this, that God has given us eternal life, and this life is in His Son. He who has the Son has the life; he who does not have the Son of God does not have the life. These things I have written to you who believe in the name of the Son of God, in order that you may know that you have eternal life. (1 John 5:11-13)

It commands us to trust Jesus Christ personally for our salvation. It is a message to be obeyed and promises the judgment of God for those who disobey (John 3:36, 1 Pet. 4:17, 2 Thess. 1:8). It asserts that Jesus Christ, through His substitutionary death, is the only way of salvation (John 14:6, Acts 4:12). The central message of the Christian gospel is the uniqueness of Jesus as the only way to God. There is salvation in none other.

Obviously, the exclusiveness of the Bible’s message invites a challenge to its authority. The authority behind such a message is absolutely basic. It is of critical significance.

B. The search for truth

What is truth? The question of Greek philosophers, echoed by Pilate, has been asked by millions down through the centuries. Is there any truth? Where is it? What is the criterion of truth? When a Christian steps forward to answer these questions, one finds oneself immediately embroiled in the controversy over authority.

C. The threat to the unity of the church

In the days of the apostle Paul, cracks began to appear in the building of God—the church. The deepest and most serious could be traced to the problem of authority. In Ephesus, Timothy was cautioned against accepting as an authority the profane babblings of the Gnostics (1 Tim. 6:20, 21), which threatened the unity of the church.

The question of authority still divides Christians today. James I. Packer says:

It is the most far-reaching and fundamental division that there is, or can be, between them. The deep cleavages in Christendom are doctrinal; and the deepest doctrinal cleavages are those which result from disagreement about authority. Radical divergences are only to be expected when there is no agreement as to the proper grounds for believing anything.2

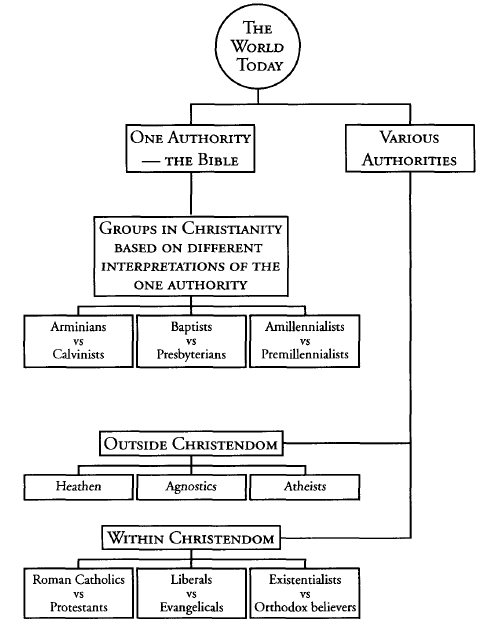

Doctrinal divisions within Christendom may be sorted into two general classifications according to their basis of authority, suggests Packer.3

Many with doctrinal differences actually work from the same basic authority—that is, the Word of God. Arminians and Calvinists differ in their theology, yet both acknowledge the Scriptures to be their sole authority. So also Baptist and Presbyterians or amillennialists and premillennialists.

These agree that there is one authority only—the Scriptures. However, they disagree on what the Scriptures teach. This raises an interesting question. How can the Scriptures be considered as authoritative when they are subject to various interpretations? For the moment, this question will have to be put on the shelf.

There is a second major classification within Christendom however. This class includes the wide variety of groups that rest their case upon different authorities.

For the traditionalist, the authority is tradition; for the existentialist, the authority is personal experience. The rationalist’s authority is reason. The evangelical’s authority is the Bible.

Hence, Protestants and Roman Catholics differ in their theology because they differ in their authorities. So also, liberals and evangelicals, existentialists and orthodox believers.

Outside Christian thought there are the heathen, the atheist, the agnostic and others. These differ with one another as well as with other groups because they differ in their authorities.

Here, then, are the three major reasons why the problem of authority is the most fundamental problem we face: the Christian’s message, the world’s search and the church’s destiny.

Project Number 1

Using the chart above as a guide, place these names in the appropriate places on the following chart.

|

Billy Graham |

Francis Schaeffer |

|

Guru Maharaji ji |

New Age Movement |

|

Thomas Paine |

Hare Krishna |

|

Transcendental Meditation |

Charles Colson |

|

Corrie Ten Boom |

Mohammed Ali |

The problem we faced in my study that afternoon was no new problem. In my corner I had said, “No! Stop! Change!” In the other corner Karen had said, “Why? I can’t! I don’t want to!” In another corner of her mind stood her parents, her church and her Christian friends. Opposite them stood her boyfriend and her society. What a dilemma!

II. The Real Question

Although she felt sure the question was whether to leave or not to leave, that was not the real question. For an hour we sparred, with little progress because I failed to see the root problem. As soon as it was exposed I asked, “Karen, what is the authority for your conduct as a Christian?”

That is it! What is your standard for measuring truth, for marking right and wrong? What is your criterion? What is the ultimate authority for your faith and conduct? This is the real question I pressed upon the conscience and life of my friend that afternoon. There are four popular standards on the scene today. I was not sure where to categorize Karen. I knew, however, that her next words would do that for me. It would put her in one of the following four folds.

A. The Rule of Reason

This is the criterion of the rationalist. In a rationalist the intellect reigns supreme. The premise is this: If it is reasonable, it is true! If it is not reasonable, I cannot accept it.

The rationalist’s basic assumption is that the mind in its processes is capable of discovering, organizing and stating truth. Actually there are two categories of rationalists as they relate to the Word of God.

1. Reason without the Scriptures

Some such persons totally reject the Scriptures as revelation. These are the atheists, the agnostics, the skeptics and the infidels. To Thomas Paine, Ingersoll and Voltaire, revelation and reason were mutually exclusive.

After writing some fine pamphlets on freedom, including The Rights of Man, Thomas Paine wrote The Age of Reason and said it would destroy the Bible. He claimed that within one hundred years Bibles would be found only in museums or in musty corners of second-hand bookstores.

Ingersoll held up a copy of the Bible and said, “In fifteen years I’ll have this book in the morgue.” Fifteen years rolled by and Ingersoll was in the morgue, but the Bible lives on.

Voltaire’s reason rejected the Scriptures also. He predicted that in one hundred years the Bible would be an outmoded and forgotten book. When the one hundred years had passed, Voltaire’s house was owned and used by the Geneva Bible Society. And note this. Recently ninety-two volumes of Voltaire’s works—a part of the Earl of Derby’s library—were sold for two dollars.

2. Reason above the Scriptures

Others recognize the Bible as literature of worth, but place their reason above the Scriptures. These are the theological liberals. Packer suggests that such a person accounts for the Bible this way:

Scripture is certainly a product of outstanding religious insight. God was with its authors. They were inspired to write, and what they wrote is inspiring to read. But their inspiration was not of such a kind as to guarantee the full truth of their writings, or to make them all the Word of God. Like all human products, Scripture is uneven. One part contradicts another; some parts are uninspired and unimportant; some of it reflects an antiquated outlook which can have no relevance for today. (The same, of course, on this view is true of church tradition). If the essential biblical message is to mean anything to modern man, it must be divorced from its obsolete trappings, reformulated in the light of modern knowledge and restated in terms drawn from the thought-world of today. Reason and conscience must judge Scripture and tradition, picking out the wheat from the chaff and refashioning the whole to bring it into line with the accepted philosophy of the time.4

But is reason really adequate? Pascal, the French philosopher and mathematician, pointed out that the supreme function of reason is to show us that some things are beyond reason. And surely they are.

Reason as the ultimate authority is not an authentic Christian position. The darkness of the human mind prevents it from being such.

But a natural man does not accept the things of the Spirit of God; for they are foolishness to him, and he cannot understand them, because they are spiritually appraised. (1 Cor. 2:l4)

In whose case the god of this world has blinded the minds of the unbelieving that they might not see the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God. (2 Cor. 4:4)

This I say therefore, and affirm together with the Lord; that you walk no longer just as the Gentiles also walk, in the futility of their mind, being darkened in their understanding, excluded from the life of God, because of the ignorance that is in them, because of the hardness of their heart. (Eph. 4:17, 18)

One of the most staggering statements in Scripture relative to this subject comes from the pen of Paul. He writes, “There is none who understands” (Rom. 3:11). The verb the Holy Spirit uses here occurs twenty-six times in our New Testament but is reserved for a peculiar use. It is invariably used for understanding divine things. Our Lord uses it for understanding the things of the kingdom (Matt. 13:13, 14, 15, 19, 23, 51). Paul speaks of understanding what the will of the Lord is (Eph. 5:17).

Although people think they understand, and they talk and write extensively on the subject, yet humanity, by nature, understands nothing about God or truth!

George Whitefield, a master preacher, once was depicting a blind man with his dog, walking on the brink of a precipice. His foot was almost slipping over the edge. The description was so graphic, the illustration so vivid and life-like, that Lord Chesterfield sprang up and exclaimed, “Good God! He’s gone!”

But “Whitefield answered, “No, my lord, he is not quite gone; let us hope that he may yet be saved.” Then he went on to speak of the blind man as a man being led by his reason. What a graphic way of showing that a man led only by reason is ready to fall into hell!

If reason is not a legitimate authority, what is? For centuries a mainstream within Christendom has proposed a second standard—tradition.

B. The Test of Tradition

This is the criterion of the traditionalist, who is frequently found in Roman Catholicism, the Orthodox tradition and some Protestant churches. For the traditionalist, the official teaching of the institutional church is the rule for life and faith.

The premise, stated simply, is this: “To learn the mind of God one should consult the church’s historic tradition; what the church says, God says.”5

The basic assumption is that the Bible is not a sufficient and complete revelation. Packer again is very helpful here.

This view does not question that the Bible is God-given and therefore authoritative; but it insists that Scripture is neither sufficient nor perspicuous, neither self-contained nor self-interpreting, as an account of God’s revelation. The Bible alone, therefore, is no safe nor adequate guide for anyone. However, tradition, which is also God-given and therefore authoritative, supplies what is lacking in Scripture; it augments its contents and declares its (alleged) meaning.6

Rome paved the way in this direction and has gone furthest down the road. It was the Council of Trent in 1546 that declared tradition of equal authority with the Bible. It stated that the Word of God is contained both in the Bible and in tradition and urged every Christian to give them equal veneration. The Vatican Council of 1870 proclaimed infallibility of the pope in matters of faith and morals.

While rationalism and modernism take away from the Word of God, this position adds to it. The position of the Roman Catholic church is clearly and succinctly stated by Loraine Boettner who writes:

She maintains that alongside of the written Word there is an oral tradition, which was taught by Christ and the apostles but which is not in the Bible, which rather was handed down generation after generation byword of mouth. This unwritten Word of God, it is said, comes to expression in the pronouncements of the church councils and the papal decrees. It takes precedence over the written Word and interprets it. The pope, as God’s personal representative on the earth, can legislate for things additional to the Bible as new situations arise.7

Devoted followers in this church are required to make this confession:

I also admit the holy Scriptures, according to that sense which our holy mother Church has held and does hold, to which it belongs to judge of the true sense of interpretation of the Scriptures; neither will I ever take and interpret them otherwise than according to the unanimous consent of the Fathers.8

But is this a legitimate Christian stance? Hardly, for several reasons. Let me mention briefly only three.

There is, first of all, the unreliability of oral tradition. The disputed doctrines are without any biblical validation or any support from the writings of the fathers in the second and third centuries. Therefore, for hundreds of years that which is allegedly tradition was passed on orally. Can such material be placed on equal authority with the written Scriptures? If it was revealed truth, why is there no written record of it earlier? If it was merely reported repeatedly from one generation to the next for several generations, what guarantee is there of its genuineness?

Also, the contradictions in early tradition make it suspect. Boettner graphically demonstrates this point when he writes:

The church Fathers repeatedly contradict one another. When a Roman Catholic priest is ordained, he solemnly vows to interpret the Scriptures only according to “the unanimous consent of the Fathers.” But such “unanimous consent” is purely myth. The fact is they scarcely agree on any doctrine. They contradict each other, and even contradict themselves as they change their minds and affirm what they previously had denied. Augustine, the greatest of the Fathers, in his later life wrote a special book in which he set forth his Retractions. Some of the Fathers of the second century held that Christ would return shortly and that He would reign personally in Jerusalem for a thousand years. But two of the best known scholars of the early church, Origen (185-254), and Augustine (354-430), wrote against this view. The early Fathers condemned the use of images in worship, while later ones approved such use. The early Fathers almost unanimously advocated the reading and free use of the Scriptures, while the later ones restricted such reading and use. Gregory the Great, bishop of Rome and the greatest of the early bishops, denounced the assumption of the tide of Universal Bishop as anti-Christian. But later popes, even to the present day have been very insistent on using that and similar titles which assert universal authority. Where, then, is the universal tradition and unanimous consent of the Fathers to papal doctrine?9

Finally, the oral tradition does not complete, but rather nullifies the Scriptures. Consider the most prominent doctrines and practices of this church, their distinctives if you like, and compare them to Scripture: the papacy (cf. Matt. 22), the priesthood (cf. 1 Pet. 2:5, 9), the celibacy of the priests and nuns (cf. Gen. 2:18), the use of images in worship (cf. Ex. 20:4, 5), worship of the Virgin Mary (cf. Matt. 4:10), penance and indulgences (cf. Eph. 2:8, 9), prayers for the dead (cf. Heb. 9:27), the mass (cf. Heb. 9:28) and purgatory (cf. Luke 16:23).

Each of these and a host of others are founded solely on tradition and appear to oppose the teachings of Scripture.

It is indeed difficult to resist the conclusion of Boettner who says:

We insist, however, that it would have been utterly impossible for those traditions to have been handed down with accuracy generation after generation by word of mouth and in an atmosphere dark with superstition and immorality such as characterized the entire church, laity and priesthood alike, through long periods of its history. And we assert that there is no proof whatever that they were so transmitted. Clearly the bulk of those traditions originated with the monks during the Middle Ages.10

One of the most remarkable trends in the religious world today is the breaking up of this foundation. Many adherents to such churches are saying that final authority does not really lie in the church, but ultimately in the conscience of men. This brings us to the third criterion.

Although a remnant still hold to them, the rule of reason and the test of tradition are largely past. Our generation has witnessed the rise of a “new cult of madness.” In it “reason” and “logic” are dirty words. Thinking is repudiated. Age-old petrified planks of tradition are trampled under foot. A new sovereign has been crowned—experience.

C. The Empire of Experience

This is the criterion of the existentialist. Feelings reign supreme.

The premise is: If it feels good, do it! Or, in the words of Ernest Hemingway, “What is good is what I feel good after, and what is bad is what I feel bad after.”11

The basic assumptions of an existentialist are few but forceful. The present is all-important. As a result, the existentialist seeks to divorce life from the past and the future. History, traditions and established standards are worthless and irrelevant. Here is the spring out of which gushes a flood of rebellion.

The existentialist is skeptical of prophecy and any long-range plans for ones life or for society. The future is unsure. After all, why worry about a tomorrow threatened by nuclear warfare? The existentialist forgets about tomorrow. Hear it from one of them. Dr. Alan Watts, writer, philosopher and interpreter of Zen Buddhism, speaking to a group of students at the Dallas Memorial Auditorium several years ago on the subject “What if there is no future?” said, “Get on centre ... live in the eternal now.”

More than this, the existentialist is totally sold out to subjectivism. There is no objective authority beyond oneself. The existentialist lives in a sea of subjectivity. Feelings are all that matter.

Is experience as the ultimate authority an authentic Christian position?

To listen to many Christians one would think so. Recently I heard a brilliant lecture by Dr. Earl Radmacher, president of Western Conservative Theological Seminary in Portland, Oregon. He spoke of those who use the testimonial of a changed life as their authority. They say, “It must be right, it changed my life.” Beware my friend! Christianity has no corner on changed lives. Rennie Davis, one of the Chicago Seven, is a changed man today. How? He is a devoted disciple of the fifteen-year-old Guru Maharaji ji. Who does not know of a friend whose life has been revolutionized by Transcendental Meditation or Yoga? Such testimonials conclusively demonstrate that experience, in itself, is no criterion.

Dr. Radmacher further spoke of those who from the pulpit declare their intimate experience with the Lord as final authority. He reminded us of the defender of the faith who marshals several standard proofs of the resurrection of Christ, then concludes, “But the greatest proof of all is this: I spoke with Him today!” Where is the final authority? Experience. You see the pitfall, don’t you? What shall we say to the person who says he has never spoken to Him? If his experience is his final authority, he has destroyed the very essence of the Christian faith.

The contemporary version of this experience criteria is expressed most prominently in postmodernism, the present-day reaction to the exalted position modernity (from the eighteenth century Enlightenment) has given to reason and science. In our postmodern world (since the mid-20th century) there is no such thing as absolute truth. Personal experience has replaced the scientific method with its rationalism. Truth is personal, individualistic and relative.

If one’s personal experience is the authority, the human race is set adrift on the sea of subjectivity with no compass, chart or anchor. Is this to be accepted as a legitimate Christian position? Not at all.

Though in the philosophical, psychological, sociological and theological fields this “cult of madness” flourishes, it is a usurper of the throne—an illegitimate sovereign.

Sanctify them in the truth; Thy word is truth. (John 17:17).

And you shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free. (John 8:32).

What, then, is the ultimate authority?

D. The Standard of Scripture

This is Sola Scriptura. It is the deep and earnest conviction that Scripture is God’s holy and infallible Word and that it is the only source of revealed theology. It alone is the rule of a Christians creed and conduct. What it does not determine cannot be said to be a part of Christian truth.

In 1580, in an attempt to effect agreement among the Lutherans, there was prepared the Formula of Concord. It expresses the orthodox Protestant position:

We believe, teach and confess that the prophetic and apostolic writings of the Old and New Testaments are the only rule and norm according to which all doctrines and teachers alike must be appraised and judged.

This is our answer to the problem of authority.

In the words of the Westminster Confession:

The whole counsel of God, concerning all things necessary for His own glory, man’s salvation, faith and life, is either expressly set down in Scripture or by good and necessary consequence, may be deduced from Scripture unto which nothing at any time is added, whether by new revelations of the Spirit, or traditions of men (1:6).

The supreme judge, by which all controversies of religion are to be determined, and all decrees of councils, opinions of ancient writers, doctrines of men, and private spirits, are to be examined and in whose sentence we are to rest, can be no other but by the Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture (1:10).12

In the days of the Reformation, the primary subject under debate was the doctrine of salvation. Yet at the very heart of the Reformation was the matter of authority. The position of the Reformers was simply that the Bible, not the church, not reason and not experience, was the final authority.

On trial for heresy, Martin Luther acknowledged this authority when he said, “I put the Scriptures above all the sayings of the fathers, angels, men and devils. Here I take my stand.” Again he said, “My conscience is subject to the Word of God.”

The authority of the Scriptures is one of the inescapable implications of revelation and inspiration.

Granted that God did reveal Himself to the human authors (revelation) and that these authors, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, did record accurately what was revealed to them (inspiration), what are the implications for the Scriptures?

We have already asserted the inerrancy of these writings. But there is now another implication. This one will complete our equation.

Revelation + Inspiration = Inerrancy + Authority

If the Bible is a divine revelation that has been God-breathed, then it logically follows that these Scriptures must be absolutely authoritative for every person who names the name of Jesus Christ.

This is more than a logical inference, however.

Project Number 2

The Bible claims to be authoritative. This claim can be supported from four directions.

1. Read: Exodus 31:18; Deuteronomy 4:13; Deuteronomy 10:5; 2 Samuel 23:2. The Old Testament claims such authority for _________________________.

There are thousands of occurrences of “thus saith the Lord.” The religion of Israel was based upon the authority of the written Word of God.

2. Read John 10:35. Much later the Lord claims this same authority for ______________.

B. B. Warfield recognized the depth of this text when he wrote,

Now, what is the particular thing in Scripture, for the confirmation of which the indefectible authority of Scripture is thus invoked? It is one of its most casual clauses—more than that, the very form of its expression is one of its most casual clauses. This means, of course, that in the Saviour’s view, the indefectible authority of Scripture attaches to the very form of expression of its most casual clauses. It belongs to Scripture through and through, down to its most minute particulars, that it is of indefectible authority.13

Our Lord recognized its authority when He used it to rebuke Satan (Matt. 4), when He taught He came to fulfill it (Matt. 5:17), when He submitted to it (Matt. 26:24, 53, 56) and when He taught it to His disciples (Luke 24:27).

3. Read Matthew 24:35.

It can also be said that the Lord claims authority for ______________.

Our Lord earlier makes a powerful point when He places His own words above the teaching and traditions of Judaism in the Old Testament Scriptures. He says, “But I say to you, that every one who looks on a woman to lust for her has committed adultery with her already in his heart” (Matt. 5:28).

4. Read 1 Corinthians 14:37; 1 Thessalonians 2:13.

It is obvious that the apostles claim the full authority of God for _____________.

These apostles were obviously conscious of their delegated authority (Acts 10:41, 42; 1 Thess. 2:13; Gal. 1:1, 11, 12; 1 Cor. 2:13; 14:37; 2 Cor. 13:3, 5, 10; 1 Thess. 5:27; 2 Thess. 3:14). They were foundational in the creation of the church (Eph. 2:20) and presented their instructions as from God (2 Cor. 11:4; 2 John 10). That their authority was so recognized by the early church is clear from Acts 2:42 and 2 Peter 3:2.

III. The Ultimate Witness

But what is really the ultimate basis for the Bible’s authority? In the final analysis, the authority of the Bible comes from its author. If it is divine revelation, and if it is God-breathed, then it is absolutely the final authority in every area of doctrine and practice. The doctrine it teaches comes to us with all the authority of God Himself. The demands it makes upon daily life patterns come with all of the authority of God.

This was the fact I sought to establish with Karen that day. The ultimate authority in the life of a Christian is the Word of God. It had become obvious that all my arguments were to no avail. It was just as obvious that the real issue was the question of authority in her life. Finally, in desperation, as a last resort, I turned her to the Bible. Together we looked up 1 Thessalonians 4:3-6. In a hushed voice she read aloud:

For this is the will of God, your sanctification; that is, that you abstain from sexual immorality; that each of you know how to possess his own vessel in sanctification and honor, not in lustful passion, like the Gentiles who do not know God; and that no man transgress and defraud his brother in the matter because the Lord is the avenger in all these things, just as we also told you before and solemnly warned you.

As she read and reread the verses I waited for the impact. Oh that she would hear it as an authoritative word from God.

In such situations, many times the person has looked up and said, “I am not convinced.” How does one become convinced of the authority of the Word of God? Is it by devastating argumentation? Or is it by a dozen proofs? Surely the answer is “No.”

What then is the confirmation of its authority?

One of the old theologians, Voetius (1648-1669), has clearly stated the classical doctrine of authority. He says:

As there is no objective certainty about the authority of Scripture, save as infused and imbued by God the Author of Scripture, so we have no subjective certainty of it, no formal concept of the authority of Scripture, except from God illuminating and convincing inwardly through the Holy Spirit. As Scripture itself, as if radiating an outward principle by its own light (no outsider intervening as principle or means of proof or conviction), is something aksiopiston (worthy of belief) or credible per se and in se—so the Holy Spirit is the inward, supreme, first, independent principle, actually opening and illuminating the eyes of the mind, effectually convincing us of the credible authority of Scripture from it, along with it, and through it, so that being drawn we run, and being passively convinced within, we acquiesce.14

For those of us who speak street English, Voetius is simply saying that belief in the authority of Scripture is derived not from argumentation, but from the inner persuasion of the Holy Spirit. This was precisely the position of the Reformers. They believed that the certainty the Bible deserves with us is attained by the testimony of the Spirit.

It is the Holy Spirit in the believer who witnesses to the truth.

And the one who keeps His commandments abides in Him, and He in him, And we know by this that He abides in us, by the Spirit which He has given us. (1 John 3:24)

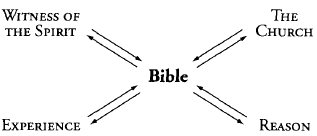

While on the one hand the evangelical Christian still cries loudly Sola Scriptura, on the other hand he also speaks frequently of the Holy Spirit, the church, reason and experience. How do these relate to each other?

IV. An Important Integration

The ultimate and final authority in the Christian faith is Scripture. The Word of God by virtue of its divine authority is our objective and full authority. This is Sola Scriptura.

This authority is confirmed by the witness of the Holy Spirit to those so enlightened by God. The truthfulness and authority of its interpretations are confirmed by the Spirit of God, who inspired them. On the other hand, the objective Scriptures are the authority and they test the genuineness of that which we may think is the witness of the Spirit. The Holy Spirit will never teach or guide in a way that will contradict the Word of God. The Word apart from the Spirit is cold orthodoxy and intellectualism. The Spirit apart from the Scriptures is subjectivism and mysticism. The Spirit confirms the authority of the Word, and the Word tests the authenticity of the Witness.

However, the Holy Spirit indwells the entire Christian community, the church (Eph. 2:22, 1 Cor. 3:16). The authority of the Scriptures and authenticity of any interpretation then, will be confirmed by their widespread or general recognition in the church at large, the community which is so enlightened. However, we certainly must never put the authority of the church above the authority of the Scriptures. The Word of God must always be the test of any interpretation or declaration by the church. But no careful Bible student will ever want to ignore the interpretations of great men of God in ages past.

And what shall we say about reason and Scripture? The authority and integrity of the written Word is clearly confirmed by the enlightened reason of humankind. History, archaeology and science combine with enlightened reason to bear testimony of Scripture. Sir William Herschel, English astronomer and discoverer of the planet Uranus, comments, “All human discoveries seem to be made only for the purpose of confirming more and more strongly the truths that come from on high, and are contained in the sacred writings.” Revelation must be examined to be received.

Yet human reason must always be tested by the Bible. Only that which is consistent with divine revelation is valid and reliable. Man’s reason stands under God’s Word. Reason cannot be the source of truth. It is incapable of inaugurating revealed truth, but it can and must test it.

So it is with the personal experience of believers. Our experiences confirm the Scriptures as the Word of God. A bumper sticker says, “God is not dead, I spoke with Him today.” Alfred H. Ackley, the hymn writer, says:

I serve a risen Savior, He’s in the world today;

I know that He is living whatever men may say;

I see His hand of mercy, I hear His voice of cheer,

And just the time I need Him He’s always near.

He lives, He lives, Christ Jesus lives today!

He walks with me and talks with me along life’s narrow way.

He lives, He lives, salvation to impart!

You ask me how I know He lives—?

He lives within my heart.

And yet experience must always be tested by the Word of God and therefore is subject to its authority (1 John 4:1-5). Many people today make extravagant claims of extraordinary experiences. Some are certainly psychologically induced phenomena. Others surely are satanic or demonic. Still others may be of God. Which are from God? Only those that can be tested and proven by the Scriptures! Our subjective experiences must always be subject to the checks of the objective revelation. For example, Paul’s experience on the road to Damascus, when he saw the Christ, is controlled by the objective revelation of the resurrection of Christ (1 Cor. 15:1-19). It must always be so. And so the relationships can be charted like this:

As Karen read and pondered the verses again her eyes became moist. Soon the tears were flowing. The work of the Spirit of God was evident that afternoon. Quietly she was acknowledging the authority of Scripture. Hesitatingly she was bowing to it. What a beautiful sight this is to behold. Unfortunately it is not a common one.

V. The Current Crisis

In an article published in Interpretation, Gordon D. Kaufman sadly but correctly wrote:

The Bible no longer has unique authority for Western man. It has become a great archaic monument in our midst... . It is no longer the Word of God (if there is a God) to man... . Only in rare and isolated pockets—and surely those are rapidly disappearing forever—has the Bible anything like the kind of existential authority and significance which it once enjoyed throughout much of Western culture and certainly among believers.15

Why is this so? Why is there such a weak attitude toward the authority of the Bible today?

Project Number 3

Carefully reflect on the situation in your life, home, church, school and country. What are the major reasons for such a weak attitude toward the authority of the Scriptures among evangelical Christians today?

1.

2.

3.

4.

The real question that faced my tearful friend that day was a question of authority. I asked what was the ultimate authority for her life? To be sure, this question was extremely relevant. Because the area of conduct we were discussing clearly fell within the scope of Scripture, it could not have been more appropriate. In many a dilemma, however, the question of authority is entirely irrelevant.

Have you ever wondered, How far does the authority of the Bible extend? What is the range of its authority? This is not easily answered, but it cannot be avoided.

VI. Barbed Boundaries

Obviously its scope is limited. It does not tell me which political party to join. It does not dictate my career. Many aspects of our social life are apart from its explicit instructions. Much liberty is granted in the area of recreation, entertainment, styles of dress and means of transportation. It does not declare what kind of automobile I should drive, what size of house I should purchase or what type of course I should take in college. Its scope is limited.

However, Scripture does have complete and absolute authority in its own sphere, that is, “the sphere of the self-revelation of God.”

In the words of Geoffrey W. Bromiley:

Its range is considerable. Historical authority covers the data of God’s work in history. Theological authority covers the teachings, not as human ideas about God, but as Gods authentic word about Himself. Ethical authority covers the whole range of conduct as it falls under the commandments, injunctions and intentional precedents of the Bible. Liturgical authority covers the practice and worship of the church, preaching the Word, singing God’s praise, prayer, administering the sacraments.16

Dr. Bromiley goes on to demonstrate that the Word of God also has absolute authority in many secular affairs. We are to “love one another” and “honour the king” and “be subject to every ordinance of man.”

The Scriptures, then, are no less comprehensive than they are authoritative. Their scope is broad indeed. They touch my relationship with God, Jesus Christ, the church, my wife, my children, my debtor, my creditor, my employer, an employee, my neighbours, the prime minister, my possessions, the law enforcement officer, the community, the state and so on.

In its own sphere, the Bible is absolutely authoritative. That sphere is broad indeed. It is encircled by biblical barbs that snag the consciences of Christians and dictate direction for our creed and conduct.

One cannot be confronted with such truth as this and walk away from it. It is like a fishhook with barbs so sharp that they dig deep and won’t let go. We cannot leave our subject without considering several specific and stinging implications.

VII. Life Responses

After a few moments of quiet reflection Karen raised her eyes to meet mine. Slowly she nodded her head, indicating her response to the Word of God.

Quietly she honoured God in her relationship with her boyfriend. She moved out of his house, found a job and began to grow in the Lord. So did he. A few months later my wife and I heard of their wedding plans. Today they are the centre of a Christian home.

If it is the authoritative Word of God, it calls for life responses. It demands obedience, instant obedience, implicit obedience. There is only one way to live the Christian life. It is “by the Book!”

The acid test of conversion is here. The Master Himself said, “You are My friends, if you do what I command you” (John 15:14).

Hudson Taylor said, “God cannot, will not, does not bless those who are living in disobedience. But only let us set out in the path of obedience, and at once before one stone is laid upon another, God is eager, as it were, to pour out His blessing.” Don’t settle for anything less.

Project Number 4

- Discuss the assertion “One can hardly claim to be a Christian who rejects the authority of the Scriptures.”

- What are the implications of this study for the ecumenical movement today? Can churches who disagree on the principle of authority reach any significant agreement on anything else?

Review

Before you tackle the next chapter take a second look at those questions that prepared the way for this chapter. Don’t fool yourself. It will be no waste of time. Read them over once again. Look at them carefully. Can you answer them now? When you have mastered those answers you may want to go a step or two further.

For Further Study

- What are the objective tests for determining whether or not a person is speaking the truth by the Spirit of God or error by a demonic or human spirit? (1 John 4:1-5)

- Evaluate the beliefs of the Jehovah’s Witnesses by the orthodox Protestant criterion of Sola Scriptura.

Bibliography

Boettner, Loraine. Roman Catholicism. Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1962.

Fletcher, Joseph. Situation Ethics. Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press, 1966.

Henry, Carl F. H. (ed.). Revelation and the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1970.

Packer, James I. Fundamentalism and the Word of God. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1970.

Phillips, J. B. Ring of Truth. New York, NY: The MacMillan Co., 1967.

Pinnock, Clark H. Biblical Revelation. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1971.

Warfield, B. B. The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible. Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1970.

1 James I. Packer, Fundamentalism and the Word of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1970), p. 42.

2 Ibid., p. 44.

3 Ibid., pp. 44-46.

4 Ibid., p. 50.

5 Ibid., p. 49.

6 Ibid, p. 49.

7 Loraine Boettner, Roman Catholicism (Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1962), p. 77.

8 Clark H. Pinnock, Biblical Revelation (Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1971), p. 124.

9 Loraine Boettner, Roman Catholicism, pp. 78, 79

10 Ibid., p. 79.

11 Joseph Fletcher, Situation Ethics (Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press), p. 54.

12 Clark H. Pinnock, Biblical Revelation, p. 114.

13 Benjamin B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible (Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1970), p. 140.

14 Bernard Ramm, The Witness of the Spirit (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1959), pp. 69, 70.

15 Gordon D. Kaufman, “What Shall We Do With The Bible?” Interpretation January, 1971), pp. 95-112.

16 Geoffrey W. Bromiley, “The Inspiration and Authority of Scripture,” Eternity (August, 1970), p. 20.

Related Topics: Bibliology (The Written Word)