Part III: INERRANCY — Chapter Four: Completely Trustworthy

Related Media|

Preparing the Way

|

Recently I read of a seminary student who was serving as student pastor of a small church. Expressing the concern of his congregation he asked, “My people ask me, ‘If the Bible says it, can I believe it?’”1

That’s a fair question! It is also a common and critical question. Our answer, “It is completely trustworthy.” That is what we mean by “inerrancy.”

Few subjects are more divisive.

Some people blatantly deny inerrancy. An accepted authority among spiritualists, Dr. Moses Hull, once wrote these outrageous words:

The Bible is, I think, one of the best of the sacred books of the ages. It is supposedly the sacred fountain from which two, if not three, of the greatest religions of the world have flowed... . While the Bible is not the infallible or immaculate book that many have supposed it to be, no one can deny that it is a great book... . Yet it must be confessed that the age of critical analysis of all its sayings and its environments has hardly dawned... . John R. Shannon said to his Denver audience, “We do not believe in the verbal inspiration of the Bible. The dogma that every word of the Bible is supernaturally dictated is false. It ought to be shelved away... . Verbal inspiration is a superstitious theory; it has turned multitudes in disgust from the Bible; it has led thousands into infidelity; it has led to savage theological warfare... . All these facts would show if brought out, that the Bible, like all other books, is exceedingly human in its origin. While the Bible is, none of it infallible, none of it unerring—when rightly interpreted it is, all of it, useful, all of it good.”2

Others quietly ignore it. One large denomination in North America recently chopped the word “inerrant” from its statement of faith. For years many of our most influential evangelical leaders have refused to deny it openly. Rather they have quietly chosen to refuse to affirm it.

“To those in the broader theological community, this seems an irrelevant issue, a carry-over from an antiquarian view of the Bible.”3

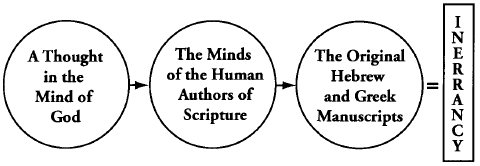

To many evangelicals, however, it is extremely important. The argument takes the form of a logical conclusion.

Granted that God did reveal Himself to the human authors and that the human authors, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, did record accurately what was revealed to them, what are the implications for the Scriptures?

Revelation + Inspiration = Inerrancy

If the Bible is a divine revelation that has been God-breathed then, they say, the inerrancy of the Scriptures naturally follows. This is what is to be explored in this chapter.

Inerrancy means different things to different people. Consider, for example, the various evangelical theories on inerrancy as summarized by H. Wayne House in the following chart.

|

Evangelical Theories on Inerrancy4 |

||

|

Position |

Proponent |

Statement of Viewpoint |

|

Complete Inerrancy |

Harold Lindsell Roger Nicole Millard Erickson |

The Bible is fully true in all its teaches or affirms. This extends to the areas of both history and science. It does not hold that the Bible has a primary purpose to present exact information concerning history and science. Therefore the use of popular expressions, approximations and phenomenal language is acknowledged and believed to fulfill the requirement of truthfulness. Apparent discrepancies, therefore, can and must be harmonized. |

|

Limited Inerrancy |

Daniel Fuller Stephen Davis William LaSor |

The Bible is inerrant only in its salvific doctrinal teachings. The Bible is not intended to teach science or history, nor did God reveal matters of history or science to the writers. In these areas the Bible reflects the understanding of its culture and may therefore contain errors. |

|

Inerrancy of Purpose |

Jack Rogers James Orr |

The Bible is without error in accomplishing its primary purpose of bringing people into personal fellowship with Christ. The Scriptures, therefore, are truthful (inerrant) only in that they accomplish their primary purpose, not by being factual or accurate in what they assert. (This view is similar to the Irrelevancy of Inerrancy view.) |

|

The Irrelevancy of Inerrancy |

David Hubbard |

Inerrancy is essentially irrelevant for a variety of reasons: (1) Inerrancy is a negative concept. Our view of Scripture should be positive. (2) Inerrancy is an unbiblical concept. (3) Error in the Scriptures is a spiritual or moral matter, not an intellectual one. (4) Inerrancy focuses our attention on minutiae, rather than on the primary concerns of Scripture. (5) Inerrancy hinders honest evaluation of the Scriptures. (6) Inerrancy creates disunity in the church. (This view is similar to the Inerrancy of Purpose view.) |

Complete inerrancy declares the Scriptures to be completely trustworthy in all they affirm. There is total agreement among advocates of this position in terms of their view of the theological or spiritual message. They may, however, differ in their understanding of the scientific and historical references. In contrast to Lindsell, for example, Nicole regards scientific and historical elements as phenomenal.5 That is,

[T]hey are reported as they appear to the human eye. They are not necessarily exact; rather they are popular descriptions, often involving general references or approximations. Yet they are correct. What they teach is essentially correct in the way they teach it.6

I. A Closer Look

What then do we mean when we speak of the inerrancy of Scripture? We mean it is completely truthful and trustworthy in all of its teachings. Though the expressions may vary, the essence is consistent in a multitude of popular and current statements.

James Cottrell, writing on the inerrancy of the Bible, says,

It means “without error, mistake, contradiction or falsehood.” It means “true, reliable, trustworthy, accurate, infallible.” To say that the Bible is inerrant means that it is absolutely true and trustworthy in everything that it asserts; it is totally without error.7

Dr. Charles C. Ryrie makes a helpful distinction when he writes,

Inerrant means “exempt from error” and dictionaries consider it a synonym for infallible which means “not liable to deceive, certain.” Actually there is little difference in the meaning of the two words, although in the history of their use in relation to the Bible, “inerrant” is of much more recent use.8

By many today, infallibility is used in reference to faith and morals, while inerrancy is used in reference to the entire text of the Scriptures.

In spite of its problems, inerrancy is a word that captures the essence of the reliability of Scripture. James Boice quotes Paul Feinberg, who gave us a careful and expanded definition when he wrote,

Inerrancy means that when all the facts are known, the Scriptures in their original autographs and properly interpreted will be shown to be wholly true in everything they teach, whether that teaching has to do with doctrine, history, science, geography, geology or other disciplines or knowledge.9

Pause for a moment to consider the importance of the above phrase “properly interpreted.” This is a crucial factor in the doctrine of inerrancy. Authors obviously used common and accepted figures of speech as poetic languages (i.e., the mountains singing), phenomenal language (i.e., the sun standing still), and the rounding off of numbers. More than that, they apparently rearranged chronology to suit their purpose or interest. This is quite evident in the Gospels. These and a dozen other elements must be incorporated into a “proper interpretation of Scripture” and allowed within the scope of inerrancy.

At the Chicago summit meeting of the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy in October, 1978, several hundred key evangelical leaders signed this statement:

Being wholly and verbally God-given, Scripture is without error or fault in all its teaching, no less in what it states about God’s acts in creation and the events of world history, and about its own literary origins under God, than in its witness to God’s saving grace in individual lives.10

The Lausanne Covenant addressing the authority and power of the Bible declares, “We affirm the divine inspiration, truthfulness and authority of both Old and New Testament Scriptures in infallible rule of faith and practice.”

The doctrinal basis of the Evangelical Theological Society states, “The Bible alone, and the Bible in its entirety, is the Word of God written and is therefore inerrant in the autographs.”

The World Evangelical Fellowship affirms “[t]he Holy Scriptures as originally given by God, divinely inspired, infallible, entirely trustworthy; and the supreme authority in all matters of faith and conduct.”

The doctrine on inerrancy, then, asserts four things:

- The Scriptures are without error. They are wholly true.

- This applies to the original writings of the authors.

- They are without error in everything:

--doctrine and ethics;

--history and science.

- They are wholly true in all they affirm or teach.

II. The Defence

The arguments in support of the doctrine of inerrancy generally fall into four broad categories: inferential, deductive, inductive and historical.

A. The Inferential Argument

This has been expressed in the terms of the equation

Revelation + Inspiration = Inerrancy

The inference of inerrancy is inescapable. If it is inspired, it is inerrant. If it is God-breathed, it is trustworthy. Pope Leo XIII recognized this when he wrote:

For all the books ... are written wholly and entirely, with all their parts, at the dictation of the Holy Spirit, and so far is it from being possible that any error can coexist with inspiration, that inspiration not only is essentially incompatible with error, but excludes and rejects it as it is impossible that God Himself, the Supreme Truth can utter that which is not true.11

Although he was incorrect in describing inspiration as “the dictation of the Holy Spirit,” he was surely correct in his inference that error cannot coexist with inspiration.

But the claim of inerrancy is based upon more than inference.

B. The Deductive Argument

A deduction is a process of reasoning from the general to the specific. The general in this case is the character of God. What kind of God is the God of the Bible? Observe the common characteristic in these select verses.

May it never be! Rather, let God be found true, though every man be found a liar, as it is written, “That Thou mightest BE JUSTIFIED IN THY WORDS, AND MIGHTEST PREVAIL WHEN Thou art judged.” (Rom. 3:4)

And this is eternal life, that they may know Thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom Thou has sent. (John 17:3)

In order that by two unchangeable things, in which it is impossible for God to lie, we may have strong encouragement, we who have fled for refuge in laying hold of the hope set before us. (Heb. 6:18)

God is not a man, that He should lie, nor a son of man, that He should repent; has He said, and will He not do it? Or has He spoken, and will He not make it good? (Num. 23:19)

If God is true, the word He breathes must also be true. If He cannot lie, the Word of God must be inerrant.

The argument for inerrancy is actually in the form of a syllogism. By its very nature, the conclusion of a syllogism is of necessity true if the two premises are true. Here is a typical example:

All men are mortal (major premise).

Caesar is a man (minor premise).

Therefore Caesar is a mortal (necessary conclusion).

In the argument for inerrancy the syllogism is as follows:

Major Premise: Every Word of God is true—inerrant (Titus 1:2, Heb. 6:18).

Minor Premise: The Bible is God’s Word (direct assertions: Matt. 15:6, Rom. 9:6, Ps. 119:105, Rom. 3:2, Heb. 5:12; inference: 2 Tim. 3:16).

Speaking about 2 Timothy 3:16, B. B. Warfield helpfully observes:

The Greek term has ... nothing to say of inspiring: it speaks only of a “spiring” or “spiration!” What it says of Scripture is not that it is “breathed into by God,” or that it is the product of the divine “in-breathing” into its human authors, but that it is breathed out by God... . When Paul declares, then, that “every Scripture,” or “all Scripture,” is the product of the divine breath, “is God-breathed,” he asserts with as much energy as he could employ that Scripture is the product of a specifically divine operation.12

Conclusion: The Bible is inerrant, truth, without lie.

This is the necessary conclusion. It can be denied only by denying one or both of the premises.

The Bible then, makes two basic claims: it asserts unequivocally that God cannot lie, and that the Bible is the Word of God. It is primarily from a combination of these two facts that the doctrine of inerrancy comes.

The character of God requires it.

Of course, the weakness of such a deduction is transparent. The premise—the character of God—is based upon the teaching of the Bible. It is virtually a circular argument using verses from the Bible to attest to the truthful character of God, from which we deduce the Bible is trustworthy. The strength of any deduction rests in the truthfulness of the premise. If one is prepared to accept the truthfulness of God (whether or not it is based upon biblical texts) then there is some validity to this deduction. Otherwise it is not a conclusive argument. However, inerrancy does not depend upon a deduction. There is still a much more forceful line of argument.

C. The Inductive Argument

An induction is the process of reasoning from many specifics to a general conclusion. There is a host of particular phrases in the Scriptures that may be accumulated and lead to the conclusion that the Scriptures are inerrant.

Project Number 1

Consider the following verses carefully. What specific point is made in each verse that makes this verse part of the inductive process that leads to inerrancy?

John 10:35

Matthew 5:17-18

Galatians 3:16

2 Timothy 3:16

Isaiah 45:19

Proverbs 30:5, 6

Jeremiah 1:9

1 Corinthians 2:13

The confidence of Christ, the apostles and the prophets in the Scriptures argue for their total accuracy. Put together these specifics, and the general conclusion surely is that the Scriptures are inerrant.

D. The Historical Argument

Those denying inerrancy often claim that this doctrine is a recent invention. Some say it originated with Princeton theologian B. B. Warfield in the late 1880s. Others, such as Jack Rogers of Fuller Theological Seminary, trace it back to the Lutheran theologian Turretin, just after the Reformation.

Both views are wrong. Inerrancy was taught long before Calvin and Luther. Augustine said:

I have learned to yield this respect and honor only to the canonical books of Scripture. Of these alone do I most firmly believe that the authors were completely free from error.13

St. Thomas Aquinas, the great medieval theologian wrote, “Nothing false can underlie the literal sense of Scripture” (Summa Theologica I, 1, 10, ad 3). Martin Luther repeated over and over, “The Scriptures have never erred,” and “The Scriptures cannot err.”14

Erickson clarifies a critical point when he writes,

While there has not been a fully enunciated theory until modern times, nonetheless there was, down through the years of the history of the church, a general belief in the complete dependability of the Bible. Whether this belief entailed precisely what contemporary inerrantists mean by the term “inerrancy” is not immediately apparent. Whatever the case, we do know that the general idea of inerrancy is not a recent development.15

Obviously, the idea of inerrancy was not a late invention of the post-Reformation period or of the nineteenth century American theologians. It was the belief of the early church fathers and the great Reformers. It was the belief of Clement, Irenaeus and Justin Martyr, as well as Calvin and Luther.

III. What About Limited Inerrancy?

A distinct but prestigious minority of evangelical scholars strongly opposes strict inerrancy as defined above. They do not believe the Bible is inerrant in all it affirms.

They advocate a limited or partial inerrancy. According to such scholars, the Scriptures are inerrant only in revelational matters: faith and practice or doctrine and ethics. When it speaks on the deity of Christ, the salvation of man, the nature of sin or the sovereignty of God, it is entirely trustworthy.

However, such men deny the inerrancy of Scripture in matters of science and history. When it records genealogies, creation data or historical events it is not entirely trustworthy. They maintain that the critical phenomena of the Bible discredit inerrancy, for all it affirms.

For my part, the Bible does not seem to distinguish between doctrinal and historical matters. As a matter of fact, often, it is very difficult to separate the doctrine from the history (e.g., Matt. 19:4)16 If inerrancy does not extend to all that the Scriptures affirm, how can we really speak of inerrancy?

Project Number 2

- What further biblical illustrations can you offer to demonstrate there is no way to separate the doctrine from the historical event?

- How do you account for the drift from inerrancy in evangelicalism today?

Project Number 3

Discuss the validity and implications of this statement: “Inerrancy is fundamental—but it is not a fundamental of the faith.”

That is, it is fundamental and important to the issue of authority. It does reflect upon the character of God. It is an essential part of the foundation of a dynamic and mature Christian life. But it is not in the same category as the great fundamentals—the virgin birth, the deity of Christ, the substitutionary death of Christ, etc. And because it is not “a fundamental,” it should not be an issue over which fellowship with other Christians is broken.

While “militant advocates” of strict inerrancy are united in their defence of absolute inerrancy, they are divided over the priority of the doctrine. They believe inerrancy is a doctrinal watershed that one must hold to be considered evangelical. It is a fundamental doctrine, the denial of which is grounds for the severance of fellowship (e.g., Harold Lindsell).

The “peaceful advocates” believe that inerrancy is not specifically taught in Scripture and therefore is not a priority issue, not a doctrinal watershed (e.g., Carl F. H. Henry).

IV. Does Inerrancy Really Matter?

Not every evangelical believes that inerrancy really matters. Some say inspiration matters, but not inerrancy. Or they say, what is really important is a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

For several reasons, inerrancy does matter.

To deny the inerrancy of Scripture seems to be inconsistent with true discipleship to Christ. Our Lord Jesus taught that Scripture was true right down to the smallest part (Matt. 5:18). Elsewhere He declared, “The Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35). Inerrancy is important as long as Jesus is Lord, and to all who claim Him as Lord.

On this point, Boice helpfully writes:

A person’s relationship to Jesus Christ is of the highest importance. No Christian would ever want to dispute that. But how do you know Jesus except as He is presented to you in the Bible? If the Bible is not God’s Word and does not present a picture of Jesus Christ that can be trusted, how do you know it is the true Christ you are following? You may be worshiping a Christ of your own imagination. Moreover, you have this problem. A relationship to Jesus is not merely a question of believing on Him as one’s Savior. He is also your Lord, and this means He is the one who is to instruct you as to how you should live and what you should believe. How can He do that apart from an inerrant Scripture? If you sit in judgment on Scripture, Jesus is not really exercising His Lordship in your life. He is merely giving advice which you consider yourself free to disobey, believe or judge in error. You are actually the lord of your own life.17

To deny inerrancy is to undermine the authority of Scripture. Can one really embrace as “an infallible rule of faith and practice” a book one believes to contain errors, discrepancies and contradictions? Although some today profess to do so, their position is untenable. Biblical inerrancy is inseparably linked to the larger question of biblical authority. Evangelicals who deny inerrancy must show how they distinguish the truths from the errors of the Bible without, in the process, making themselves the final authority on what they will accept and reject. G. Aiken Taylor, while asking, Is God as good as His Word? writes,

The person who allows doubts about the reliability of Scripture to linger or to be nourished, will soon discover that his confidence in the authority of Scripture is shaken. Finally, his effectiveness in the use of Scripture will diminish.18

B. B. Warfield correctly observed: “The authority which cannot assure of a hard fact is soon not trusted for a hard doctrine.”19

To deny inerrancy is to open the door to their errors that will creep into the church and corrupt it doctrinally. Norman Geisler observes that Harold Lindsell has shown, in his Battle For The Bible,

... example after example of schools and institutions which began their descent into modernism by a denial of the inerrancy of Scripture. He concluded, therefore, that inerrancy is a “watershed” issue. All things being equal, once this fundamental doctrine of Scripture is denied, there is a serious crack in the dam and sooner or later there will be a collapse. That is to say, once someone cannot trust the Bible when it speaks of history or science, then his confidence is eroded on other matters, even those pertaining to salvation.20

Project Number 4

Does inerrancy really matter? How important is it really? What other arguments can you add to the three listed above?

Beware!

James Boice sounds an alarm that ought to awaken and arouse every evangelical alive today when he writes,

For the last hundred years Christians have seen the Bible attacked directly by modern liberal scholarship and have recognized the danger. Today a greater danger threatens—die danger of an indirect attack in which the Bible is confessed to be the Word of God, the only proper rule for Christian faith and practice, but is said to contain errors.

This threat is greatest because it is often unnoticed by normal Christian people. If a liberal denies the virgin birth, questions the miracles of Christ or even declares that Jesus was only a man (as many are still doing), most Christians recognize this for what it is—unbelief. They see the hand of Satan in it. He is the one who questioned the Word of God in the first recorded conversation in the Bible, “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat from any tree in the garden?’ ... You will not surely die ... God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:1, 4). But if someone pretending to be an evangelical says, “Sure I believe in the Bible as you do, but what difference does it make if there are a few mistakes in it? After all, the Bible isn’t a history book. It’s not a science book. It only tells us about God and salvation.” Many Christians fail to see that this is also an attack on the Bible and so have their faith undermined without their even knowing it.21

Review

Once again you will find it most worthwhile to take a few minutes to review the material of this chapter. Turn back to the questions under “Preparing The Way” at the start of this chapter, and be sure you are able to answer each one completely and correctly.

For Further Study

In view of the inerrancy of Scripture, how can the following problems be resolved?

1. The problem of the missing thousand: 1 Corinthians 10:8, Numbers 25:9.

2. The synoptic problem:

a) e.g., Matthew 22:42 and Luke 20:41—What did He say?

b) e.g., Luke 24:4 and Matthew 28:2—How many angels were there?

3. The problem of Abiathar: Mark 2:26 and I Samuel 21:1 ff.—Who was the high priest?

4. The problem of the mustard seed: Matthew 13:31, 32—Is it indeed the smallest seed?

Bibliography

Beagle, Dewey M. The Inspiration of Scripture. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1963.

___. Scripture Tradition and Infallibility. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1973.

Bloesch, Donald G. Holy Scripture. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1994.

Boice, James Montgomery (ed.). The Foundation of Biblical Authority. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1978.

Boice, James Montgomery. Does Inerrancy Matter? International Council on Biblical Inerrancy, 1979.

Cottrell, Jack. “The Inerrancy of the Bible.” The Evangelical Recorder, March, 1979.

Davis, Stephen T. The Debate about the Bible. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1977.

Dowey, Edward A., Jr. The Knowledge of God in Calvin’s Theology. New York, NY: Columbia, 1952.

Erickson, Millard J. Introducing Christian Doctrine. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1992.

Geisler, Norman L. “The Inerrancy Debate—What Is It All About?” Interest, November, 1978.

Lindsell, Harold. The Battle for the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1976.

___. The Bible in the Balance. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1980.

Montgomery, John Warwick (ed.). God’s Inerrant Word. Minneapolis, MN: Bethany Fellowship, 1974.

Mounce, Robert R. “Clues to Understanding Biblical Inaccuracy.” Eternity, June, 1966.

Pache, Rene. The Inspiration and Authority of Scripture. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1969.

Packer, J. I. “Fundamentalism” and the Word of God. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1958.

Pinnock, Clark H. A Defense of Biblical Infallibility. Philadelphia, PA: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1967.

Radmacher, Earl D. (ed.). Can We Trust The Bible? Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 1979.

Rogers, Jack (ed.). Biblical Authority. Waco, TX: Word, 1977.

Ryrie, Charles C. What You Should Know About Inerrancy, Revised 1977. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1981.

Schaeffer, Francis A. No Final Conflict. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1976.

Stahr, James. “Are There Errors In The Bible?” Interest, March, 1978.

___. James. “Round 2—The Battle For The Bible.” Interest, September, 1979.

Stott, John. The Authority of the Bible. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1974.

Taylor, G. Aiken. “Is God As Good As His Word?” Christianity Today, February 4, 1979.

Warfield, B. B. The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible. Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1970.

1 Millard J. Erickson, Introducing Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1992), p. 62.

2 Victor H. Ernest, I Talked with Spirits (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, 1972), pp. 41, 42.

3 Millard J. Erickson, Introducing Christian Doctrine, p. 60.

4 H. Wayne House, Charts of Christian Theology and Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1992), p. 24.

5 Harold Lindsell, The Battle for the Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1976), pp. 165, 166. Roger Nicole, “The Nature of Inerrancy,” Inerrancy and Common Sense, Roger Nicole and J. Ramsey Michaels (ed.), (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1980), pp. 71-95.

6 Millard J. Erickson, Introducing Christian Doctrine (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1992), p. 61.

7 Jack Cottrell, “The Inerrancy of the Bible,” The Evangelical Recorder, (March, 1979), p. 12.

8 Charles C. Ryrie, The Bible: Truth without Error, revised edition (Dallas Theological Seminary, 1977), p. 1.

9 James Montgomery Boice, Does Inerrancy Matter? (International Council on Biblical Inerrancy, 1979), p. 13.

10 “The Short Statement of the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy,” Statement No. 4. Published in Christianity Today, (November 17, 1978), p. 36.

11 Papal Encyclical 3292 in Heinrick Demzinger, Sources of Catholic Dogma.

12 Quoted by James Montgomery Boice, Does Inerrancy Matter? p. 15.

13 Augustine, Letters, LXXXII.

14 Martin Luther, Works of Luther XV: 1481; XIX: 1073.

15 Millard J. Erickson, Introducing Christian Doctrine, p. 62.

16 For further reading see Norman L. Geisler, “The Inerrancy Debate—What Is It All About?” Interest (November, 1978), p. 5.

17 James Montgomery Boice, Does Inerrancy Matter? pp. 24-25.

18 G. Aiken Taylor, “Is God As Good As His Word?” Christianity Today (February 4, 1977), p. 24.

19 B. B. Warfield, The Inspiration and Authority of The Bible (Philadelphia, PA: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company, 1970), p. 442.

20 Norman L. Geisler, “The Inerrancy Debate—What Is It All About?” Interest (November, 1978), p. 3

21 James Montgomery Boice, Does Inerrancy Matter? p. 28.

Related Topics: Bibliology (The Written Word), Inerrancy