7. The Patriarchal Era

Related MediaGeneral

Perhaps no period of biblical history has received more help from archaeology than this one (cf. Albright, SATC, pp. 236ff; DeVaux, BANE, pp. 111-122). Yet, it is the very conclusions of these men that have been attacked and denied at the end of the 20th century.1 In “New Archaeology,” the patriarchs are created by the imagination of a later generation.

Chronology

The date for Abraham can be derived by working back from the 480 year period between the Exodus and the fourth year of Solomon as given in 1 Kings 6:1. This involves using Solomon’s accession date which can be determined with a fair amount of accuracy although there is some disagreement concerning it.

|

4th year of Solomon |

958 After Freedman, BANE, p. 274. (Thiele = 961 B.C.) |

|

Exodus to Solomon |

480 1 Kings 6:1 1438 (Thiele = 1441) |

|

From promise to Abraham’s seed to Exodus |

430 Gen. 15:13; Acts 7:6; Exod 12:40-41; Gal. 3:17 |

|

Jacob’s age when he entered Egypt |

130 Gen. 47:9 |

|

Isaac’s age at Jacob’s birth |

60 Gen. 25:26 |

|

Years from Haran to Isaac |

25 Gen. 12:4; 21:5 |

Date Abraham entered Palestine 20832

Note: M. Anstey, Chronology of the Old Testament, pp. 56-66, argues that the 430 year figure in Exodus and Galatians includes the entire period of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in Palestine (total 215 years) so that only 215 years are involved in the Egyptian sojourn. The LXX and Samaritan Pentateuch support this interpretation. The 400 years, he believes, omit the period of Abraham’s sojourn and the 5 years before Isaac’s weaning. Following this reckoning, Joseph would have entered Egypt at roughly the same time as the Hyksos--a very tempting hypothesis. It would also place Abraham’s migration during the Amorite eruptions. However, though this interpretation is rather easy in Galatians 3:17, it is much more difficult in the other three passages. Consequently, the 430 years should be considered as applying only to the period in Egypt. The date 2083 is generally supported by Glueck.3

The City of Ur in Abraham’s Time

Abraham would have left sometime during the Gutian interlude. The period which followed is known as the 3rd dynasty of Ur (2060-1950). C. L. Wooley is the most famous excavator of the city.4 The most famous king of this dynasty is Ur-Nammu, King of Sumer and Akkad. He is famous for his ziggurat (ANE 1 #85). It was completed by Nabonidus in the neo-Babylonian era. It was 200 x 150 x 70 feet. There was much business in the sacred area. There were receipts for sacrifices and other items of trade. There were factories, workshops and about 20 houses per acre. Ur had about 24,000 residents. Ur-Nammu is also famous for what is now the earliest law code known.

The reference to the city of Ur (Gen. 11:28, 31) as being in the land of the Chaldeans has provoked much debate and speculation. Speiser says, “The mention of Ur of the Chaldeans brings up a problem of a different kind. The ancient and renowned city of Ur is never ascribed expressly, in the many thousands of cuneiform records from that site, to the Chaldean branch of the Aramaean group. The Chaldeans, moreover, are late arrivals in Mesopotamia, and could not possibly be dated before the end of the second millennium [1200-1000]. Nor could the Arameans be placed automatically in the patriarchal period. Yet the pertinent tradition was apparently known not only to P (31) but also to J (28). And even if one were to follow LXX in reading “land” for “Ur,” the anachronism of the Chaldeans would remain unsolved.” He concludes that it is intrusive, however old, and tentatively explains the intrusion as an identification of Ur (center of moon worship) with Haran (also a center of moon worship). This telescoping of two cities would have taken place later when the Chaldeans were prominent.5 Gadd also considers “Chaldean” to be anachronistic, but he does locate it in southern Mesopotamia and not up north as some do. He gives credence to “echoes of Abraham” maintained in legends and traditions for the area.6 The Arameans do not become a political force in history until the first millennium, but as Moscati says, “The one certainty arising from the modern view of their history is that their self-assertion in Syria is no longer to be regarded as coincident with their arrival in the area, but only with the formation of the states known to us.”7 In other words, the Arameans were in the area long before they became known. Is it not possible that when Moses wrote Genesis 11, that the area of Ur was in some way identified with the Chaldeans? The outlines of this problem are too uncertain for dogmatism.8

Palestine during the Patriarchal Era

The Patriarchs were nomads but not like contemporary Bedouin (read the story of Sinuhe). There is a beautiful representation of Semites in Egypt at Beni Hasan from about 1900 B.C. (ANEP, #3).

Execration texts list Canaanite names. Gezer indicates that it was probably an outpost of the Egyptians during the Patriarchal time. The temples at Megiddo indicate Egyptian influence as well.9

The Transjordan and Jordan valley indicate settlement about 2000 B.C. and a sudden departure in about the 19th century according to Glueck.10 This supports the overthrow of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Speiser argues that Genesis 14 is a historical document. It is not from sources (JEDP). Probably a translation of an Akkadian document. Tidal = Hittite Tudhalya, Arioch = sub prince of Mari, etc. He dates it in the 18th century.11

1 See the discussion in Chapter 1.

2Provan, et al., A Biblical History of Israel, p. 113, says, “This nice, neat date is not unambiguous even on biblical grounds. For one thing, all the numbers sound like round numbers, but of course this fact would only adjust the date by decades. Second, textual variation is present with some of the dates; for instance, the Septuagint understands the 430 years of Exodus 12:40 to cover not only the time in Egypt but the patriarchal period as well. Nonetheless, even with these uncertainties, the Bible itself appears to situate the patriarchs in Palestine sometime between ca. 2100 and 1500 B.C.—the first half of the second millennium B.C.”

3N. Glueck, Rivers in the Desert. See also Freedman, BANE, pp. 266-270, for a general discussion.

4See his account of “The Graves of the Kings of Ur” in Leo Deuel, The Treasures of Time.

5E. A. Speiser, Genesis in Anchor Bible, p. 80.

6C. J. Gadd, “Ur” in Archaeology and Old Testament Study (AOTS), Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967, pp. 87-101. In the same work see Parrot, “Mari.”

7S. Moscati, The Face of the Ancient Orient, p. 214.

8Cf. Provan, et al., A Biblical History of Israel, pp. 116-17 who refer to “Chaldeans” as a later updating.

9See G. E. Wright, Biblical Archaeology, pp. 48-49. See also I. Finkelstein and D. Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” BAR 20 (1993) 26-43.

10Cf. Provan, et al., A Biblical History of Israel, on Glueck’s methodology and the comment that “more recent surveys have indicated some evidence of occupation in Transjordan during the so-called ‘gap’ between Early Bronze IV and Late Bronze IIb,” pp. 136-137.

11Speiser, Genesis (on chapter 14).

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

8. Ancient Middle Eastern Culture And The Bible

Related MediaGod’s revelation did not come into a vacuum. He spoke to a people who were a part of the contemporary culture and called them to become followers of His true way. In the process, God did not ignore the culture surrounding His called ones.1 There are many points of contact with the cultures of the Mesopotamians, Canaanites, Egyptians, Hittites and others. The large question is, how much of the revelation of God is couched in terms and concepts familiar to all people in that region and how much is unique. Cross is critical of Yehezkel Kaufmann for his insistence that Israelite religion “was absolutely different from anything the pagan world ever knew.” Cross insists that this approach violates fundamental postulates of scientific historical method.2 The Evangelical will find himself in more sympathy with Kaufmann than with Cross.

Nevertheless, it is mistaken to assume that there is no connection between the Bible and its cultural milieu. Cross uses the term “epic” to describe the genre of Israel’s religious expression (in contrast to mythic). He believes that the word “historical” is a valid description of what goes on in this religious expression, but he says, “At the same time confusion often enters at this point. The epic form, designed to recreate and give meaning to the historical experiences of a people or nation, is not merely or simply historical. In epic narrative, a people and their god or gods interact in the temporal course of events. In historical narrative only human actors have parts. Appeal to divine agency is illegitimate. Thus the composer of epic and the historian are very different in their methods of approach to the materials of history. Yet both are moved by a common impulse in view of their concern with the human and the temporal process. By contrast myth in its purest form is concerned with ‘primordial events’ and seeks static structures of meaning behind or beyond the historical flux.”3

Mesopotamian culture and the Patriarchs.

Abraham and His Milieu

God called Abraham from Ur and made a unique covenant with him. The record also indicates that the main center of Patriarchal activity before coming to Palestine was Haran (Aram-Nahariam, Gen. 24:10. Padan-Aram, Deut. 26:5). Many of the place names in the region of Haran are tied in with Abrahamic history: Serug, Nahor, Terah.4

Culture at Nuzu

“Nuzi [sometimes Nuzu], modern Yorghan Tepe, about 9 miles south-west of Arrapha, modern Kirkuk, in the eastern hill-country of ancient Assyria, was excavated (1925-31) by the American Schools of Oriental Research in Baghdad, first with the Iraq Museum and later with Harvard University, under the direction of E. Chiera, R. H. Pfeiffer, and R. F. S. Starr. The settlement, originating before 3000 B.C., had, c. 2200 B.C., an Akkadian population and was called Gasur, but by 1500 B.C. its name was Nuzi and its population mainly Hurrian. The ruins, including a temple in seven levels, a palace, with some painted rooms, and many private houses, contained pottery, and other small objects. Most important, however, were some 4,000 cuneiform tablets dating c. 1500-1400 B.C. and written in Akkadian influenced by Hurrian vocabulary and idioms.”5 While the dates of these tablets are considerably later than the date for Abraham (c. 2000 B.C., though critical scholars would date the patriarchs, if they even existed, in the middle of the second millennium), the fact that the patriarchal narratives have more in common with these data than with those later in Israelite history, makes their discussion pertinent to patriarchal studies. Kitchen’s excellent little work defends the patriarchal authenticity and deals with the parallels. He also argues that the Hurrian influence has been exaggerated. Many of these parallels are found in Mesopotamia in general.6

Filial adoption

The purpose of this adoption was to provide a childless couple with care in their old age and the performance of religious rites in exchange for an inheritance. This seems to fit the action of Abraham in connection with Eliezer as a “son of his house” who would inherit from Abraham (Gen. 15:2-4).7 Weir also includes the adoption of someone into a family without sons. He believes the Jacob and Laban situation fits this description.8

Teraphim

The Teraphim stolen by Rachel were once assumed to represent property ownership.9 Kitchen believes this is a fallacious identification. He believes she took them for her own protection and blessing.10

Birthright

The importance of the birthright is stressed at Nuzi. “A double share by the principal son, normally the eldest natural son, as is definitely prescribed in Deut. xxi. 15ff.”11 At Nuzi, an eldest son might be demoted as was Reuben.

Blessings/oaths

Kitchen downplays the significance of blessing-oaths at Nuzi and of the idea of selling a birthright.12 In other words, he does not believe the Nuzi material is parallel.13

Conclusion

Weir concludes his discussion by saying, “The Nuzi documents do not mention any Old Testament incident or personage, nor do they indicate with certainty that any of Israel’s ancestors ever lived in or visited Mesopotamia. Their fifteenth-century provenance cannot accurately date patriarchal traditions since the customs they portray may have originated much earlier and may have persisted in Palestine until the monarchial period. They reveal, however, that the social customs, much of the terminology, and many of the personal names in the Pentateuch and elsewhere in the Old Testament were those current in parts of the Near East during the second millennium B.C., and to that extent they validate Israelite tradition.”14

Van Seters has led the way in trying to destroy the edifice built up in the Albright era supporting the historicity of the patriarchs. Kitchen has shown that Van Seters’ attempts to tie the patriarchal stories into the first millennium are unsuccessful.15

Culture and the Mosaic Era

Albright16 defends the general historicity of the Book of Exodus, though he believes the patriarchs were polytheistic. In so far as Moses is concerned, he makes the following observations:

“It is absurd to deny that Moses founded the Israelite religious system. He was a Hebrew born in Egypt, raised under Egyptian influence. Egyptian slave labor, Rameses, topography of eastern delta, Sinai peninsula fits, etc.”

“The Name YHWH was revealed only to Moses--Exodus 6:1; 3:14. ‘He causes to be.” Yahweh asher yihweh. Beside this fuller form there was also a normally abbreviated form Yahu (the jussive form of the imperfect causative which appears as Yahweh), which is found in all early personal names (shortened in northern Israel to -yau- and after the Exile to -yah). There is no non-Israelite name which has been put forth as an antecedent to this name which can be adequately defended. Elephantine = yaho.” Pettinato tentatively believes he has found a “ya” ending on names.17 [However, the biblical account in Exodus 3 seems to indicate a qal, the simple form].18

“An original characteristic of the Israelite God was that he stood alone, no family connections. The Sons of God (Angels and Israelites) were so by creation.”

He was not restricted to any abode. No exact spot.

Anthropomorphic--but the body was always clothed in the Kabod.

Aniconic aspect--nothing to prove Israel ever depicted God. He argues that even the calves of the northern Israel were pedestals for Jehovah.

A sacrificial system was a part of the practice of all Asiatics and particularly imbedded in Semitic thought (cf. Genesis 4).

Law codes were common to Semites (cf. Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi). The striking peculiarity of Israel is that they were commanded not to sin because Yahweh so wills it. There is a moral-ethical element present here that is not present in the other law codes of antiquity.

Was Moses a monotheist? “If by that we mean one who teaches the existence of only one God, the creator of everything, the source of justice, who is equally powerful in Egypt, Palestine and in the desert, who has no sexuality, and no mythology, who is human in form, but cannot be seen by human eye, and cannot be represented in any human form--then the founder of Yahwehism was certainly a monotheist.”19

The Bible, of course, does not begin monotheism with Moses. The majestic opening of the Bible with Bereshit …Elohim, “In the beginning God . . .” is not simply a Mosaic or later religious thought which has developed through the intellectual process of man, but is a statement of fact. Whether we speak of the time of Abraham (2000 B.C.) or of Moses (1500 B.C.) there is nothing in the surrounding situation which is conducive to monotheism. Crass polytheism has had a long history in the Mesopotamian valley when God calls Abraham out of it. The Canaanite religion as graphically depicted in the Ugaritic literature as well as in the archaeological finds is virulently hostile to monotheism. The only logical conclusion at which one can arrive is that monotheism comes only through divine revelation in a miraculous manner. If this could have happened in the time of Moses, it could have happened in the time of Abraham and, of course, did happen in the time of Adam. Historical study simply will not support the evolutionary hypothesis as an explanation of the development of monotheism.20

Ancient law codes and the Mosaic law

Ur-Nammu. Sumerian (212-2095)ANET, Supplement p. 523.

Laws of Eshnunna--ANE, p. 133 (c. 2000 B.C.) Discovered at Susa around A.D. 1900. It is Amorite and was apparently carried there.

Code of Hammurabi--ANE, p. 138ff (c. 1700 B.C.) Laws found at Ebla antedate Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi by centuries.

Compare the following:

|

|

Hammurabi |

Bible |

|

Law # |

1 |

Exod. 23:103; Deut. 5:20; 19:16-21 |

|

|

8 |

Lev. 19:11, 13; Exod. 20:15; Deut. 5:19; 22:1-4 |

|

|

14 |

Exod. 21:16; Deut. 24:7 |

|

|

21 |

Exod. 22:2-3 |

|

|

24 |

Deut. 21:1ff |

|

|

60 |

Lev. 19:23-25 |

|

|

117 |

Exod. 21:2-11; Deut. 15:12-18 |

|

|

120 |

Exod. 22:7-9 |

|

|

129 |

Deut. 22:22 |

|

|

130 |

Deut. 22:23-27 |

|

|

154 |

Lev. 18:6-18; 20:10-21; Deut. 27:20-23 |

|

|

195 |

Exod. 21:15 |

|

|

196ff |

Exod. 21:23-25; Lev. 24:19-20; Deut. 19:21 |

|

|

209 |

Exod. 21:22-25 |

|

|

250 |

Exod. 21:28-36 |

|

|

266 |

Exod. 22:10ff |

Note that only 16 out of 282 of Hammurabi’s laws bear resemblance to the biblical laws and these are usually quite general. Why are there similarities? Common institutions: marriage, government, private ownership, etc. Common problems: death, murder, theft, slavery, etc. It should be extremely unusual if there were not many points of similarity. Why are there differences? There is no need here even to discuss a common heritage as in the case of the flood. The Mosaic Law was divinely instituted. It was theocratic government as opposed to civil government in the other nations. There was no doubt utilization of many things already practiced by the people, but there is no borrowing from Mesopotamia here.21

The Sacrificial System

The origin and explanation of the sacrificial system in the Bible are very vague. Animal sacrifice appears to be taken for granted in Chapter 4 of Genesis, but its origin and significance are simply assumed. Animal sacrifice is part of all the ancient religious systems. (At Ugarit the Shelem [peace] and Asham [guilt] offerings have been identified)22 We can assume from Genesis 4 that God instituted animal sacrifices and explained to Adam their significance. This information was preserved by Noah but perverted and misunderstood by his descendants. The instruction to Moses, then, is taking at least some things which are familiar to the people and placing them in their true perspective.

The Sanctuary

Many have argued and some still do, that the tabernacle is nothing but the later temple anachronistically placed in the time of Moses. Few would hold that today even though the antiquity of the details would be denied.23

Some link the ark with a portable shrine as used by the Arabs.24 This illustrates the attempt by many to find every possible link with identifiable objects in history, however tenuous, based on a philosophy of no supernatural revelations.25

The Canaanites and Israel26

The term Canaanite is historically, geographically and culturally synonymous with the Phoenicians. Canaanite refers to a northwest Semitic people and culture of western Syria and Palestine before the 12th century B.C., and the term Phoenician refers to the same people and culture after that.

The Canaanites played an important part in history of civilization. In 3-2 millennium, they bridged the gap between Egypt and Mesopotamia, and to them we no doubt owe much of the slow, but constant transfusion of culture which we find in the ancient near east.

Forced out of Palestine and most of Syria in the 13th and 12th centuries, the Phoenicians turned their energies seaward and became the great mariners and traders of all time.

The Greeks attribute their achievements in the arts of peace to them (cf. also writing).

Inscription and Grammar Work--chiefly Gesenius

Renan--1860-61 cf. Pritchard.

Byblos--Montet--Dunand (1921- )

Ugarit--Schaeffer (1929- )

Khadattu (Arslan Tash) Thureau Dangin (1928)

Hamath (Orontes) Ingholt (1931-38)

Plains of Antioch (McEwan) (1932-37) (Around Orontes)

Mari--Parrot (1933- )

Alalakh-Wooley (1936-39)

Ugarit

Schaeffer, Excavation; C. H. Gordon--Texts.27 There were at least two consonantal alphabetic scripts which had been devised by the Canaanites. The cuneiform alphabet was used at Ugarit. The other was a direct progenitor of later Phoenician. They were also familiar with Akkadian, Egyptian hieroglyphics and Byblian syllabic characters (this is a hieroglyphic form syllabary in use toward the end of the third millennium B.C.--used to write a very early form of Canaanite).

Canaanite Culture

Among other reasons it did not reach a greater height was that it had a low religious level. The Canaanites had a primitive mythology. Their religion contained the most demoralizing cultic practices then existing in the near east. Human sacrifice, sacred prostitution, eunuch priests, serpent worship, brutal mythology.

Literature

The relation of Ugaritic to the Old Testament has been demonstrated but over-extended by Dahood especially. For a more conservative treatment, see Craige in Word Biblical Commentary Psalms.

Phoenicians

They spread the Canaanite culture, religion, language and alphabet all over the Mediterranean area.28 They established colonies as far as Spain.29 They founded Carthage (Qart-hadasht—new town, hence, several names like this). Tarshish—Smelting plant (several), Moloch--idol. Child sacrifice. For example, a stele (55 x 12 cm.) was found in a field of stelae and Urns with offering remains mostly of children in Carthage. Donner & Rollig #79. “To the Lady, to Tanat the face of Baal and to the Lords to Baal Hamon; This is what Canami slave of Eshmunamas son of Baalyatan vowed--his flesh . . .” (My translation, 3rd century, B.C.). The rest concerns warnings to those who would disturb the stone.30 Albright agrees with O. Eissfeldt that “molek was a sacrificial term and not the name of a Canaanite divinity. Punic molk and Heb. molek (vocalized correctly by MT) are in fact the same word, and both refer to a sacrifice which was, for Phoenicians and Hebrews alike, the most awe-inspiring of all possible sacred acts--whether it was considered as holy or as an abomination.”31

The Contacts with Paganism during the Time of the Judges

In the Canaanite religion El is the head of the pantheon. He has been displaced by Baal as Chronos was by Zeus. He probably declined in relative prominence during the period 2500-1500 B.C. He was still worshipped, however, at local shrines and his name is retained in El Elyon and El Olam. His wife seems to be Asherah (Ashirat in Ugaritic literature). Her longer name is “the Lady who treads on the Sea (dragon).” She is the foe of Baal and his wife/sister Anath. The word Asherah is usually translated grove (Judges 3:7) in KJV since the symbol of her presence was a sacred tree or pole.32 Mot killed Baal and took him to the underworld. Anath freed him after a violent struggle with Mot. Anath was also called the Queen of Heaven. These gods were sadistic and sexual.33 Amos and Hosea inveigh against this religious system which had completely permeated the northern kingdom.

The most important offspring of this “couple” is Baal. Baal is really a title. The names of Baal include Zabul (the exalted), Lord of Earth, Rider of the Clouds, Lord of Heaven. Baal-zebul (not zebub) in Ekron. Beelzebub is a title for Satan in the New Testament. He is also called Hadad (cf. Ben-Hadad in Scripture). The idea of Yahweh being Baal was once accepted and people named their children thusly. However, this is later looked on with disfavor because of Baal worship and these names are changed, e.g., Ishbaal = Ishbosheth (bosheth--shame).34

Ashtoreth (Astarte) is mentioned quite frequently in the Old Testament. It is not clear whether she is the wife of Baal. In any event she is the goddess of love and the Egyptians called her and Anath, goddesses who conceive but do not bear (cf. Deut. 28:4 where ashtaroth means fruit of flocks). In Phoenician Palestine Astarte grew in importance while Anath became hidden under various appellations. Her name was later fused in Aramaic as Atargatis. The Queen of Heaven, Venus, Diana, Aphrodite and Mary are all part of the virgin cult originating in the earliest days of man’s apostasy.

Dagon is a grain god who is the son of El and father of Baal in Ugaritic literature. References in Judges: Baalim, 2:11; Baal, 2:13; 10:6; Ashtoreth, 2:13; 10:6; Groves, 3:7; Altar of Baal and Grove by it, 6:25; Ephod, 8:27; Baal-berith, 8:33; house of Baal-berith, 9:4; Men of Hamor? 9:28; house of their god, 9:27; Gods of Syria, Sidon, Moab, Ammon, Philistines, 10:6; Chemosh, 11:24; Dagon, 16:23; ephod, teraphim, graven image, molten image, 18:14.

The Baal cycle portrayed in ANET, pp. 129-142 is the seasonal cycle in which Baal breeds, dies and is later revived. The sexual activity pictured in the literature was carried out in practice by the people. Small wonder God condemned the religion of the Canaanites and the later prophets inveighed against it. This kind of culture can only degrade.35

1As indicated above, an important work on this subject is John H. Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament.

2F. M. Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel, p. viii.

3Ibid., is it possible that this discussion has bearing on the current debate about contextualization of the Gospel in the missions? Does one not need to be able to distinguish between culture as a neutral issue and culture that is antithetical to the biblical revelation?

4J. Kelso, Archaeology and Our Old Testament Contemporaries, p. 19.

5C. J. Mullo Weir, “Nuzi” in AOTS, p. 73. The following discussion is based primarily on this essay.

6K. Kitchen, The Bible in Its World. See Provan, et al., A Biblical History of Israel, p. 115 for a recent discussion of Nuzi and the Patriarchs.

7Ibid., p. 70 and Weir, “Nuzi,” p. 73.

8Ibid.

9C. H. Gordon, “Biblical Customs and the Nuzu Tablets,” Biblical Archaeologist 3.1 (1940): 1-12.

10K. Kitchen, The Bible in Its World, p. 70.

11Weir, “Nuzi,” p. 76.

12Ibid., pp. 76-77.

13Kitchen, The Bible in Its World, p. 76.

14Weir, “Nuzi,” p. 83.

15Ibid., see J. Van Seters, “The Problem of Childlessness in Near Eastern Law and the Patriarchs of Israel,” JBL 87 (1968): 401-8 (See f.n. 2 for a list of Nuzi text publications); Abraham in History and Tradition, 1975.

16W. F. Albright, SATC.

17K. Kitchen, The Bible in Its World, p.47.

18Cf. Segal, Pentateuch, only the meaning is revealed, not the name at this time. Cf. also John Day “Religion of Canaan” in Anchor Bible Dictionary 1:834, who agrees with me on the Qal form.

19Albright, SATC, p. 272. Albright’s point of view, of course, has been completely rejected by modern secular writers. The data has not changed; only the interpretation.

20Cf. Albright’s own views on the evolution of religion, Ibid., pp. 170ff. He quotes with favor anthropologist Fr. Schmidt (Ursprung der Gottsidee) who argues that the existence of “high” gods among present primitive peoples points to monotheism. At least, he says, Schmidt has disproved the fetishism-polytheism-monotheism approach.

21See Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament, p. 293 for a comparison.

22W. F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel, p. 59.

23See Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel.

24See Wright, BA, chapter 7.

25For further reading from a critical point of view see Eissfeldt, The Old Testament an Introduction, Wright, Biblical Archaeology, Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel, and SATC, DeVaux, History of Israel. From an evangelical point of view, see Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament.

26See W. F. Albright, Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan. Also “The Role of the Canaanites in the History of Civilization” in BANE. See also F. M Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. More recently J. Van Seters, In Search of History and Jonathan N. Tubb, Canaanites in Peoples of the Past.

27See ANET.

28For a further discussion, see A. Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, pp. 356-57.

29See J. G. Scheuer, “Searching for the Phoenicians in Sardinia,” BAR 16:1 (1990) 53-60.

30Carthage was traditionally founded in 814 B.C., although nothing prior to 750 B.C. has been found archaeologically (time of Uzziah). The Carthaginians became famous in history through the Punic (corruption of Phoenician) Wars (264-241, 218-201, 149-146). Carthage was destroyed during the final war.

31W. F. Albright, Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan, p. 236. But see also Diana Edelman, “Biblical Molek Reassessed,” JAOS 107 (1987) 727-31. For child sacrifice at Carthage see Stager and Wolf, “Child Sacrifice at Carthage, BAR 10/1 (1984) 37-51 and Patricia Smith, “Infants Sacrificed? The Tale Teeth Tell,” BAR 40/4 (2014) 54-56, 68.

32See “Queries & Comments,” BAR 40:3 (2014) 8 for the debate on this meaning between Dever and Lipinski.

33ANET, p. 139, h.I AB.

34Cf. Hosea 2:16, “You will call me Ishi (my man) and you will no longer call me Baali (my husband).

35Source for this discussion: Ernest. R Lacheman, Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

10. Egypt, 1600-1000 B.C.

Related MediaThe New Kingdom, Dynasties XVIII-XX, 1600-1000 B.C.

General

The wars of liberation were successful in driving out the dreaded Hyksos under the XVIIth dynasty (see Unit 6). The XVIIIth dynasty proceeded with a vengeance (1) to exterminate every vestige of Hyksos influence and (2) to reestablish Egyptian control of Palestine.

The Empire

The XVIIIth dynasty acquired an empire in Syro-Palestine and became the most powerful state in the Middle East.

Amenhotep I (1545-1525) He reached the Euphrates.

Thutmose III (1490-1436)

He conquered Syria in twenty years of fighting. He crossed the Euphrates and defeated the Mesopotamian states. He was the most powerful of all Pharaohs. His son, Thutmose IV, married a Mitannian princess.1

Amenhotep IV (1364-1347)

He brought the kingdom into decline. He broke with the Amon priesthood at Thebes, established a new capital (Akhetaten--Tell-el-Amarna), a new religion (worship of Aten, the sun disc), changed his name (Akhenaton--pleasing to Aten) and introduced a naturalistic art style.2 The religion was, at best, henotheism not monotheism. Because of this new direction of energy, the kingdom began to decline.

The Amarna Letters

A cache of cuneiform correspondence in Akkadian was discovered at Akhenaton’s capital. These letters contain pleas to the Pharaoh as their suzerain for help against the invading Habiru.3

After Akhenaton, names from a new dynasty feature gods from the north, Re, Seth, Ptah (Ramases, Setis, Mer-ne-Ptahs). They also moved the capital to Tanis/Zoan on the delta while maintaining Thebes as a regional and seasonal capital.4

Ramases II (1290-1224)

He was the greatest Pharaoh of the XIXth dynasty. He tended to take past glories to himself and to erect colossal statues of himself. The Ramaside dynasty began in obscurity. Ramases II fought the Hittites at Kadesh in 1286 with a resultant peace treaty.5

The Israelite Exodus

This problem will be taken up in more detail in the next unit. Scholars (if they even hold to an Exodus) who hold the late date will see Ramases II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus because of the name of the city in Exod. 1:11 as well as the location of the biblical events in northern Egypt. Unger argues that Ramases II merely took credit for the city and the biblical reference was modernized.6 Wood,7 following Albright’s identification of the Ramasides with the Hyksos, believes that it was the Hyksos who oppressed Israel and that the city had been called Ramases in their time.8

The Sea People (c. 1200)

The eruption of Anatolians which terminated the Hittite Empire also had a devastating effect on Egypt. The Egyptians were barely able to beat them off and were never again able to regain their influence in Palestine-Syria (see the unit on Philistia).9

The Twentieth Dynasty c. 1200-1069

This dynasty began with Setnakht whose relationship with his predecessors (if any) is unknown. His son Ramases III strengthened Egypt militarily and was able to repel three invaders--Libyans, Sea Peoples (including the Philistines) and later the Libyans again. Both he and his predecessors forcibly settled captured Libyans in the south-east Delta. This allowed the Libyan groups who became so important later to develop. Ramases IV,V,VI,VII,VIII,IX,X,XI: most of these were short, insignificant reigns (1166-1069). There was a decline in royal power and control until Ramases XI who ruled for 29 years. In the nineteenth year of Ramases XI there was a “renaissance” and the dates are from that era. There were two strong men ruling under the weak king. “So from the 19th year of Ramesses XI (c. 1080 B.C.), all of Egypt and Nubia were divided into two great provinces, each under a chief whose common link and sole superior was the pharaoh. The boundary point was El Hibeh which became the northern base of the Theban ruler. Thus, under the last Ramesses a basic political pattern was established that was to last for over three centuries, through the 21st Dynasty and down to Prince Osorkon and the final collapse of the fractured unity of the post-imperial Egypt.”10 The story of Wenamun takes place in the fifth year of this era (1076 B.C.).11

Dates come from Campbell in BANE; cf. also Gardiner, Egypt of the Pharaohs. These dates are tentative, and, therefore, any efforts to fit the biblical data into Egyptian events must remain tentative. The dates that follow are principally from K. A. Kitchen. The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 B.C.). See also H. R. Hall, in CAH, “The Eclipse of Egypt,” 3:251-269 (1929).12

|

THE NEW KINGDOM |

||

|

The Eighteenth Dynasty 1570-1304 |

||

|

Date |

Pharaoh |

Data |

|

1525-1508 |

Thutmose I |

Moses Born 1520 |

|

1508-1490 |

Thutmose II |

Hatshepsut was Thutmose I’s only child by his official wife. Thutmose II, of a lesser wife, was married to her. Their only child was a girl. Thutmose III was from a minor wife of Thutmose II. |

|

1490-1469 |

Hatshepsut |

Could she be the princess who reared Moses? |

|

1490-1436 |

Thutmose III |

He chafed as co-regent with his stepmother until her death. Moses became 40 in 1480. The Exodus would be 1441. |

|

1436-1410 |

Amenhotep II |

His mummy has been found. Some argue that he was the Pharaoh of the Exodus (The Bible does not say he drowned. He led the battle to the water’s edge. The Psalm description is a general figurative statement). |

|

1410-1402 |

Thutmose IV |

His dream inscription may indicate that he was not originally intended to be Pharaoh. (Therefore, his brother would have died in the plagues).13 |

|

1402-1364 |

Amenhotep III |

Conquest 1400-1393 (?). |

|

1364-1347 |

Amenhotep IV (Akhenaton) |

Amarna letters 1347-1346 |

|

|

Semenkhkere |

Son-in-law of Amenhotep IV |

|

1346-1337 |

Tutankhamun |

Son-in-law of Amenhotep IV. But he may have been a son of Amenhotep III or a son of Amenhotep IV. He died young.14 |

|

1337-1333 |

Ay |

|

|

1333-1304 |

Haremhab |

|

|

The Nineteenth Dynasty c. 1304-1200 |

||

|

1304-1303 |

Ramases I |

|

|

1303-1290 |

Seti I |

|

|

1290-1224 |

Ramases II |

The greatest name in the nineteenth dynasty was Ramases II who reigned 67 years (half of which was probably coregency). He took much glory to himself. He confronted the Hittites and concluded a treaty with them. |

|

1223-1211 |

Merenptah |

His first successor was Merenptah who accomplished significant things, but he was older and therefore his reign was relatively short. His “stela” listing the kings of the Levant whom he allegedly defeated includes the only reference to “Israel” in all known Egyptian writing.15 The successors of Merenptah were weak and inefficient. The power of the throne swiftly declined under princes who followed. |

1CAH, 2,2:83. The god Aten, the religion that absorbed Amenhotep IV, began to come into prominence probably as early as Thutmose III (CAH 2,1:343). Mitanni was an Indo-European power from c. 1500-1350 B.C.

2Note samples in ANEP #’s 402ff. ANET, 108, 109, 110.

3C. Pfeiffer, The Tell El Amarna Tablets, p. 52 and ANET, pp. 483-90.

4Wilson, The Burden of Egypt, p. 239.

5See Moscati, The Face of the Ancient Orient, p. 114.

6Archaeology and the Old Testament, p. 149.

7Leon Wood, Survey of Israel’s History, p. 93.

8See SATC, p. 223. CAH 2,1:312, “A fragment of an alabaster vessel found in the tomb of doubtful ownership, bears the name of Auserre Apophis and of a princess named Herit. Its discovery has prompted the suggestion that the royal house of the 18th dynasty was linked by marriage to the Hyksos house.”

9For a discussion in a Greek context, see CAH 3:633ff. And see the delightful piece about Wenamon in ANE, pp. 16-24.

10Kitchen, Third Intermediate Period, 250-51.

11ANET, 25-29.

12For a good summary of Egyptology and the Old Testament, see DeVries in New Perspectives on the Old Testament.

13Unger, Archaeology and the Old Testament, 142-143; ANET, 449. CAH 2,1:321, “This fanciful tale …suggests that Thutmose IV was not his father’s heir apparent, but had obtained the throne through an unforeseen turn of fate, such as the premature death of an elder brother.”

14Cf. Montet, Egypt and the Bible, 148.

15ANEP, #343.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

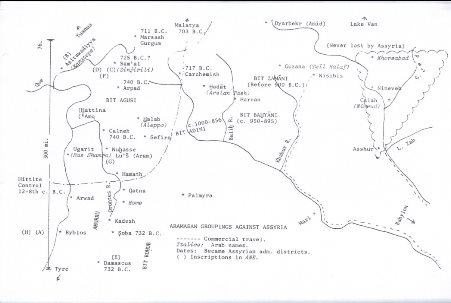

16. Israel/Judah And Assyria

Related MediaEarly Period—2000-1800.

The homeland of Assyria was in the northeast corner of the Fertile Crescent where the Tigris River flows southward across the plains, and the mountains of Kurdistan loom up in the background. The city which gave its name to the country and empire, even as it took its own name from the national god, was Ashur. It was located strategically on a low bluff on the right bank of the Tigris at a place now called Qalat Sharqat (cf. Gen. 10, Nimrod).1

Assyria first appeared historically after the time of the Kingdom of Accad to whose sphere of influence it had belonged (2300-2100 B.C., but this early period is vague). The Assyrians had colonies in Asia Minor where they carried on extensive trade (see the Cappadocian Tablets and the unit on the Hittites—see the tablet at ANE #56). These were interrupted by the rise of the Hittite state. There is a governor from the neo-Sumerian period ruling in Assyria (2000-1900 B.C.).

The Old Kingdom--1800-1700.

The Old Kingdom centers on the person of Shamshi-Adad I (1813-1781 B.C.).2 He had inherited a territory near Mari with which he came into conflict. He may have moved against Babylon. At any rate, he captured a town on the Tigris River which opened up Assyria to him. Assyria had just regained her independence from the south. From his Assyrian throne, he moved west and eventually conquered Mari. The whole of upper Mesopotamia was now in his control and the Cappadocian colonies began to show renewed activity. His son, Ishme-Dagon, was able to retain only Assyria. Mari fell back to the original Amorite dynasty through Zimrilim.

Hammurabi conquered Mari and perhaps Assyria and began the Old Babylonian Empire.

The Period of Decline--1700-1300 B.C.

During this period, Assyria was dominated by others. Mitanni seems to have controlled Assyria (see Unit 9 for Mitanni). Mitanni was defeated by the Hittites (1380-1340 B.C.), and thus the Assyrians were free to resume their expansion.

The Middle Kingdom--1300-1100 B.C.

The Middle Assyrian Kingdom arose in the 14th and 13th centuries. It was reconstituted about 1100 B.C. Names appear here which are better known in the New Assyrian Kingdom: Ashur-uballit (I), Adad-nirari (I), Shalmaneser (I), Tiglath-Pileser (I). There was a decline from 1100 to 900 B.C.3

The New Kingdom--900-600 B.C.

Assyria rose to the height of its power at the time of the New Kingdom. The Assyrians subjugated all of Mesopotamia, including Babylonia, and the border regions. They also extended their rule over a part of Asia Minor, all Syria, and, for a while, even over Egypt.

The rise of the New Assyrian Kingdom began in the 9th century under the kings Ashurnasirpal II (884-859 B.C.) and Shalmaneser III (859-824 B.C.) who energetically advanced as far as middle Syria without being able to establish lasting control there.

Then the succession of the great Assyrian conquerors began with Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 B.C.). They conquered Syria and Palestine, as well as other lands, and undertook frequent campaigns there. They include Shalmaneser V (727-722 B.C.), Sargon II (722-705 B.C.), Sennacherib (705-681 B.C.), and Esarhaddon (681-669 B.C.ANE#121) who undertook several campaigns against Egypt and occupied the Delta and the old royal city of Memphis.

The last goal of Assyrian expansion, the overthrow of Egypt, was brought very close. Esarhaddon’s son and successor, Ashurbanipal (669-631 B.C.), could indeed still garrison the upper Egyptian royal city of Thebes, but, under him, the Egyptian adventure soon came to an end, and the decline of the Assyrian might began.

This decline came about swiftly under his successors. In 612 B.C., the Assyrian capital city of Nineveh fell to a combined attack of the Medes and Neo-Babylonians. In Mesopotamia, and in Syro-Palestine, the Neo-Babylonian Empire then succeeded the Assyrian Kingdom.

Major Assyrian Kings in the New Kingdom.

Ninth Century

Ashur-nasir-pal II (884-859 B.C.)ANE 1 #118).

He established a ferocious reputation. His capital was at Calneh (Nimrud).4 Layard excavated simultaneously at Calneh and Nineveh. Most of his work was done at the acropolis. The outstanding discovery was the palace of Ashur-nasir-pal II. It contained huge winged bulls and human figures. The black obelisk of Shalmaneser III was discovered here in December, 1846. (It was almost lost at sea in a storm.)

Shalmaneser III (859-825 B.C.ANE#155).

Sixth year (853 B.C.). “In the year of (the eponym) Daian-Ashur, in the month Aiaru, the 14th day, I departed from Nineveh. I crossed the Tigris and approached the towns of Giammu on the river Balih…I departed from Aleppo and approached the two towns of Irhuleni from Hamath. I departed from Argana and approached the city of Karkara. I destroyed, tore down and burned down Karkara, his royal residence. He brought along to help him 1,200 chariots, 1,200 cavalrymen, 20,000 foot soldiers of Hadad-ezer of Damascus, 700 chariots, 700 cavalrymen, 10,000 foot soldiers of Irhulei from Hamath, 2,000 chariots, 10,000 foot soldiers of Ahab, the Israelite, 500 soldiers from Que, 1,000 soldiers from Musri, 1000 chariots, 10,000 soldiers from Irqanata, 200 soldiers of Matinu-ba’lu from Arvad, 200 soldiers from Usanata, 30 chariots, 10,000 soldiers of Adunu-ba’lu from Shian, 1,000 camel-(rider)s of Gindibu’, from Arabia [. . .],000 soldiers of Ba’sa, son of Ruhub, from Ammon‑-(all together) these were twelve kings. They rose against me [for a] decisive battle. I fought with them with (the support of) the mighty forces of Ashur, which Ashur, my lord, has given to me, and the strong weapons which Nergal, my leader, has presented to me, (and) I did inflict a defeat upon them between the towns Karkara and Gilzau. I slew 14,000 of their soldiers with the sword, descending upon them like Adad when he makes a rainstorm pour down. I spread their corpses (everywhere), filling the entire plain with their widely scattered (fleeing) soldiers. During the battle I made their blood flow down the hur-pa-lu of the district.”5

This battle is not mentioned in the Bible. These twelve kings decided that they needed to put a stop to the westward expansion of the Assyrians. Ahab of Israel and Hadad-ezer of Damascus, normally bitter enemies, joined the coalition as allies. Shalmaneser claimed complete victory, but it was several years before he returned.6 Kitchen believes the “Musri” are Egyptians.7 This would be a token force in support of Byblos, an ally of Egypt. Since Ahab’s two sons ruled 12 years (parts of years combined), and Jehu paid tribute in 841 B.C. to Shalmaneser, Ahab must have died in 853.8 His death occurred when he resumed hostilities with Damascus over Ramoth-Gilead (1 Kings 22).

On Shalmaneser’s black obelisk is a depiction of Jehu bowing down to Shalmaneser to pay his tribute (ANE 1 #100A, B). “The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri; I received from him silver, gold, a golden saplu-bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king, (and) wooden puruhtu”9 Since Jehu’s payment of tribute can be dated by Assyrian chronology to 841 B.C., these two dates become the last year of Ahab and the first of Jehu.

Adad Nirari III (810-783 B.C.)

Jehoahaz was ruling in the north and Joash in the south. “In the fifth year (of my official rule) I sat down solemnly on my royal throne and called up the country (for war). I ordered the numerous army of Assyria to march against Palestine. I crossed the Euphrates at its flood. As to the numerous hostile kings who had rebelled in the time of my father Shamshi-Adad (V) and had wi[th held] their regular (tributes)…I received all the tributes […] which they brought to Assyria. I (then) ordered [to march] against the country Damascus. I invested Mari’ in Damascus [and he surrendered]. One hundred talents of gold (corresponding to) one thousand talents of [silver], 60 talents…[I received as his tribute].”10

This battle, likewise, is not recorded in the Bible, but it has far-reaching effects on the future of both Judah and Israel. We read in 2 Kings 13:7, during Jehu’s son Jehoahaz’ rule, ‘For he left to Jehoahaz of the army not more than fifty horsemen and ten chariots and 10,000 footmen, for the king of Aram had destroyed them and made them like the dust at threshing.”

The crushing of Damascus by Adad Nirari removed the dreaded Aramean oppression and allowed a renascence of Israel and Judah. Under Jeroboam II in the North and Uzziah (Azariah) in the south (both with long reigns) there was great prosperity.11 During this period of prosperity, Hosea and Amos preached against the violations of the covenant and promised that God’s punishment would be the captivity.

Eighth Century

Tiglath-pileser III (745-727 B.C. ANE#119)

This monarch brought Assyria to new life. Isaiah, in chapter 1, uses language to describe the state of Judah that sounds as though they have undergone a siege. “Your land is desolate, your cities are burned with fire, your fields—strangers are devouring them in your presence; it is desolation as overthrown by strangers” (Isaiah 1:7). Isaiah began his ministry in the last days of Uzziah (Isaiah 6 may be inaugural; in which case, the call would have come in the same year Uzziah/Azariah died. 2 Chron. 26:22 says that Isaiah wrote “Acts of Uzziah.” This could have been done after Uzziah’s death, but more likely would have come during some of the life of Uzziah. Thus, I would say “in the last days of Uzziah.”). The question is of what devastation does this speak? Tadmor argues that the reference in Tiglath-pileser’s annals to a certain Azirau from Juda can only refer to our Azariah/Uzziah.12 Some scholars reject the equation, but Tadmor’s arguments are cogent. How could there be two Judah’s and two Azariah’s from the very same period?

Tiglath-pileser says “[In] the (subsequent) course of my campaign [I received] the tribute of the kin[gs…A]zriau from Iuda in…countless, (reaching) sky high…eyes, like from heaven…by means of an attack with foot soldiers…He heard [about the approach of the] massed [armies of] Ashur and was afraid…. I tore down, destroyed and burnt [down …for Azr]iau they had annexed, they (thus) had reinforced him…like vine/trunks…was very difficult…was barred and high …was situated and its exit…I made deep…I surrounded his garrisons [with earthwork], against…I made them carry [the corvee-basket] and…his great…like a pot [I did crush…] (lacuna of three lines)…Azriau…a royal palace of my own [I built in his city…] tribute like that [for Assyrian citizens I imposed upon them . . .] the city Kul[lani…] his ally…the cities…19 districts belonging to Hamath and the cities in their vicinity which are (situated) at the coast of the Western Sea and which they had (unlawfully) taken away for Azariau, I restored to the territory of Assyria. An officer of mine I installed as governor over them. [I deported] 30,300 inhabitants from their cities and settled them in the province of the town Ku[…]; 1,223 inhabitants I settled in the province of the Ullaba country.”13

Of King Menahem of Israel, the Bible says, “There came against the land Pul [Tiglath-Pileser III],14 the King of Assyria, and Menahem gave Pul a thousand talents of silver, that his hand be with him to confirm the kingdom in his hand” (2 Kings 15:19). Tiglath-Pileser III’s annals say, “[As for Menahem, I ov]erwhelmed him [like a snowstorm] and he…fled like a bird, alone, [and bowed to my feet (?)]. I returned him to his place [and imposed tribute upon him, to wit:] gold, silver, etc. Israel [Omri land], all its inhabitants (and) their possessions I led to Assyria.”15

Ahaz was attacked by Syria and Ephraim, probably around 735, when he first came to the throne. This coalition first began to threaten Judah in the latter days of Jotham, Ahaz’ father. The usual interpretation is that Syria and Ephraim are forming an anti-Assyrian coalition and do not dare leave their southern flank uncommitted. Consequently, they planned to put a certain “Ben Tabel” on the throne.16

The chronology is difficult. Kings (2 Kings 16:5) tells us that Rezin and Pekah waged war on Jerusalem, but could not conquer him. Chronicles (2 Chron. 28:5-15) tells us that there was a tremendous slaughter of Jews and that 200,000 were taken captive. They were subsequently released under the prophecy of a certain Oded. Further, Isaiah 7:1-3 tells us that word has come back to Ahaz that “Syria is resting on Ephraim.” This indicates a coalition and apparently further action against Jerusalem. It was at this point that Isaiah confronted Ahaz and challenged him to trust in Yahweh, but Ahaz has already made up his mind to go to Assyria (2 Kings 16:7-9). This meant that Ahaz and Judah became vassals of Assyria and also subordinated themselves to the gods of Assyria. The sequence of events must have been something like this: a major attack was made against the fortified cities of Judah with devastating results (much as when Sennacherib came west in 701 B.C.). However, the goal of defeating Jerusalem and Ahaz directly so as to put an anti-Assyrian on the throne failed. Consequently, Syria and Ephraim had decided to come back later to complete the task. This was what frightened Ahaz and his advisers so badly that they sent to Tiglath-pileser for help.17

Tiglath-pileser gladly responded. He says, “I laid siege to and conquered the town Hadara the inherited property of Rezon of Damascus [the place where] he was born. I brought away as prisoners 800 (of its) inhabitants with their possessions…their large (and) small cattle…of the 16 districts of the country of Damascus I destroyed (making them look) like hills of (ruined cities over which) the flood (had swept)…Israel…all its inhabitants (and) their possessions I led to Assyria. They overthrew their king Pekah and I placed Hoshea as king over them. I received from them 10 talents of gold, 1000(?) talents of silver as their [tri]bute and brought them to Assyria.”18 This took place after his ninth year or after 736 B.C.

The Bible says (2 Kings 15:29-30), “In the days of Pekah king of Israel Tiglath-pileser king of Assyria came and captured Ijon, Abel-beth-maacah, Jaoah, Kedesh, Haor, Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali; and he carried the people captive to Assyria. Then Hoshea the son of Elah made a conspiracy against Pekah the son of Remaliah ad struck him down, and slew him and reigned in his stead.”

Shalmaneser V (727-722 B.C.)

Hoshea sat on the Israelite throne at the pleasure of Assyria. Under Tiglath-pileser’s successor (Shalmaneser V), Hoshea foolishly refused to send tribute to Assyria and turned to a certain “So” of Egypt (2 Kings 17:1-4). “And the king of Assyria found conspiracy in Hoshea; for he had sent messengers to So king of Egypt, and offered no present to the king of Assyria, as he had done year by year” (2 Kings 17:3-4). “And it came to pass…that Shalmaneser king of Assyria came up against Samaria, and besieged it. And at the end of three years they took it…and the king of Assyria carried Israel away unto Assyria, and put them in Halah…and in the cities of the Medes” (2 Kings 18:9-11).

There is much debate about the identity of this Egyptian, but see my notes on Osorkon where Kitchen believes that “So” is an abbreviation for Osorkon. Whoever he was, he was in no position to oppose Assyria, and Hoshea was left twisting in the wind. Shalmaneser apparently began the siege, and Sargon II finished it when Shalmaneser died.

Sargon II (722-705 B.C.ANE 1 #120)

Sargon says, “(Property of Sargon, etc., king of Assyria, etc.) conqueror of Samaria and of the entire (country of) Israel who despoiled Ashdod (and) Shinuhti, who caught the Greeks who (live on islands) in the sea, like fish, who exterminated Kasku, all Tabali and Cilicia, who chased away Midas king of Musku, who defeated Musur in Rapihu, who declared Hanno, king of Gaza, as booty, who subdued the seven kings of the country Ia’, a district on Cyprus, (who) dwell (on an island) in the sea, at (a distance of) a seven-day journey.” “I besieged and conquered Samaria, led away as booty 27,290 inhabitants of it. I formed from among them a contingent of 50 chariots and made remaining (inhabitants) assume their (social) positions. I installed over them an officer of mine and imposed upon them the tribute of the former king. Hanno, king of Gaza and also Sib’e, the turtan of Egypt set out from Rapihu against me to deliver a decisive battle. I defeated them; Sib’e ran away, afraid when he (only) heard the noise of my (approaching) army, and has not been seen again. Hanno, I captured personally.”19 Sargon’s claim to have defeated Samaria agrees with neither the biblical data nor Shalmaneser V’s annals. As Finegan suggests, Sargon may have come to the throne on the heels of the defeat of Samaria and carried out the deportation begun by Shalmaneser V.20

In 711 B.C. Sargon put down a rebellion in Ashdod. Shabako, the Nubian, was ruling Egypt at that time. Isaiah used this incident to show Judah the utter futility of expecting Egypt to give them help against Assyria. “Even as My servant Isaiah has gone naked and barefoot three years as a sign and a token against Egypt and Cush, so the king of Assyria will lead away the captives of Egypt and the exiles of Cush, young and old, naked and barefoot with buttocks uncovered, to the shame of Egypt. Then they shall be dismayed and ashamed because of Cush their hope and Egypt their boast. So the inhabitants of this coastland will say in that day, ‘Behold, such is our hope, where we fled for help to be delivered from the king of Assyria; and we, how shall we escape?’” (Isaiah 20:3-6). Sargon’s description is quite vivid and shows that Judah was conspiring (under Hezekiah) to throw off the Assyrian yoke.21

Seventh Century

Sennacherib (705-681 B.C.)

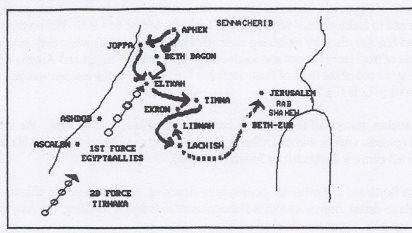

Sennacherib ruled at the end of the eighth century and beginning of the seventh. The northern kingdom exists no more and Hezekiah is on the throne in Judah as an unwilling vassal of Sennacherib. (2 Kings 18, ANEP. 200; for Lachish, see ANE 1 #101). Isaiah has been trying to get the Judeans to trust in Yahweh for deliverance, and that is what happened in 701 B.C. when Sennacherib came west to put down a concerted rebellion.

“In my third campaign I marched against Hatti, Luli, king of Sidon, whom the terror‑inspiring glamor of my lordship had overwhelmed, fled far overseas and perished. The awe‑inspiring splendor of the ‘Weapon’ of Ashur, my lord, overwhelmed his strong cities (such as) Great Sidon, Little Sidon, Bit Zitti, Zaribru, Mahalliba, Ushu (i.e. the mainland settlement of Tyre), Akzib (and) Akko, (all) his fortress cities, walled (and well) provided with feed and water for his garrisons, and they bowed in submission to my feet. I installed Ethba’al upon the throne to be their king and imposed upon him tribute (due) to me (as his) overlord (to be paid) annually without interruption.

“As to all the kings of Amurru—Menahem from Samsimuruna, Tuba’lu from Sidon, Abdili’ti from Arvad, Urumilki from Byblos, Mitinti from Ashdod, Buduili from Beth‑Ammon, Kammusunadbi from Moab (and) Aiarammu from Edom, they brought sumptuous gifts and—fourfold—their heavy ( ) presents to me and kissed my feet. Sidqia, however, king of Ashkelon, who did not bow to my yoke, I deported and sent to Assyria, his family‑gods, himself, his wife, his children, his brothers, all the male descendants of his family. I set Sharruludari, son of Rukibtu, their former king, over the inhabitants of Ashkelon and imposed upon him the payment of tribute (and of) ( ) presents (due) to me (as) overlord—and he (now) pulls the straps (of my yoke)!

“In the continuation of my campaign I besieged Beth‑Dagon, Joppa, Banai‑Barka, Azuru, cities belonging to Sidqia who did not bow to my feet quickly (enough); I conquered (them) and carried their spoils away. The officials, the patricians and the (common) people of Ekron—who had thrown Padi, their king, into fetters (because he was) loyal to (his) solemn oath (sworn) by the god Ashur, and had handed him over to Hezekiah, the Jew—

(and) he (Hezekiah) held him in prison, unlawfully, as if he (Padi) be an enemy—had become afraid and had called (for help) upon the kings of Egypt (and) the bowmen, the chariot(‑corps) and the cavalry of the king of Ethiopia, an army beyond counting—and they (actually) had come to their assistance. In the plain of Eltekah, their battle lines were drawn up against me and they sharpened their weapons. Upon a trust(‑inspiring) oracle (given) by Ashur, my lord, I fought with them and inflicted a defeat upon them. In the melee of the battle, I personally captured alive the Egyptian charioteers with the(ir) princes and (also) the charioteers of the king of Ethiopia. I besieged Eltekah (and) Timnah, conquered (them) and carried their spoils away. I assaulted Ekron and killed the officials and patricians who had committed the crime and hung their bodies on poles surrounding the city. The (common) citizens who were guilty of minor crimes, I considered prisoners of war. The rest of them, those who were not accused of crimes and misbehavior, I released. I made Padi, their king, come from Jerusalem and set him as their lord on the throne, imposing upon him the tribute (due) to me (as) overlord. [See map of Battle of Eltekah, p. 132].

“As to Hezekiah, the Jew, he did not submit to my yoke, I laid siege to 46 of his strong cities, walled forts and to the countless small villages in their vicinity, and conquered (them) by means of well‑stamped (earth‑) ramps, and battering‑rams brought (thus) near (to the walls) (combined with) the attack by foot soldiers, (using) mines, breeches as well as sapper work. I drove out (of them) 200,150 people, young and old, male and female, horses, mules, donkeys, camels, big and small cattle beyond counting, and considered (them) booty. Himself I made a prisoner in Jerusalem, his royal residence, like a bird in a cage. I surrounded him with earthwork in order to molest those who were leaving his city’s gate. His towns which I had plundered, I took away from his country and gave them (over) to Mitinti, king of Ashdod, Padi, king of Ekron, and Sillibel, king of Gaza. Thus I reduced his country, but I still increased the tribute and the katru‑presents (due) to me (as his) overlord which I imposed (later) upon him beyond the former tribute, to be delivered annually. Hezekiah himself, whom the terror‑inspiring splendor of my lordship had overwhelmed and whose irregular and elite troops which he had brought into Jerusalem, his royal residence, in order to strengthen (it), had deserted him, did send me, later, to Nineveh, my lordly city together with 30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver, precious stones, antimony, large cuts of red stone, couches (inlaid) with ivory, nimedu‑chairs (inlaid) with ivory, elephant-hides, ebony‑wood, box‑wood (and) all kinds of valuable treasures, his (own) daughters, concubines, male and female musicians. In order to deliver the tribute and to do obeisance as a slave he sent his (personal) messenger.”22

There was a battle between Egypt and Sennacherib at Eltekah (see map p. 132.23 The Egyptians were routed under Taharqa, then a prince not a king, but God routed the Assyrian army supernaturally.

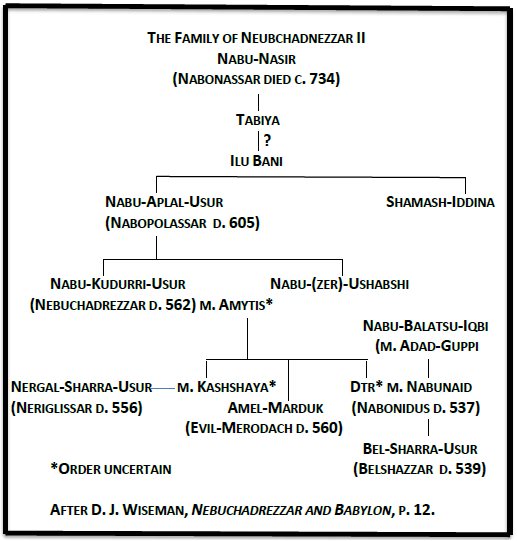

In spite of the evidence of God’s divine deliverance of the city of Jerusalem, Hezekiah decided he must look elsewhere for help. Consequently, he turned to the rising Chaldean group in southern Mesopotamia. They were a part of the Assyrian empire, but these “Bit Yakin” as the Assyrians called them, kept revolting against their overlords. In 702 Merodach-baladan sent messengers to Hezekiah apparently to encourage him to join an anti-Assyrian coalition in the west. (The date is debated. If it is 702, then Hezekiah received the ambassadors prior to Sennacherib’s invasion. Further, the placement of Isaiah 38-39 would point to the Babylonian emphasis of 40-66). Isaiah warns Hezekiah of the futility of his move and speaks of the fall of Babylon in 13-14. I believe, with S. Erlandson that the fall of Babylon in Chapters 13-14 refers to Sennacherib’s attack on Babylon in 689, just about a decade after the visit of the ambassadors.24 Isaiah is showing that leaning on Babylon for help against Assyria will not work, for Assyria will defeat Babylon.25 Sennacherib finally became fed up with this constant rebellion and went south to raze the city. He says, “In my second campaign I advanced swiftly against Babylon, upon whose conquest I had determined, like the oncoming of a storm I broke loose, and I overwhelmed it like a hurricane. I completely invested that city, with mines and engines my hands (took the city), the plunder…his powerful…whether small or great, I left none. With their corpses I filled the city squares (wide places). Shuzubu, king of Babylonia, together with his family and his (nobles) I carried off alive into my land. The wealth of that city,—silver, gold, precious stones, property and goods, I doled out to my people and they made it their own…The city and (its) houses,—foundation and walls, I destroyed, I devastated, I burned with fire. The wall and outer wall, temples and gods, temple-tower of brick and earth, as many as there were, I razed and dumped them into the Arahtu-canal. Through the midst of that city I dug canals; I flooded its site with water, and the very foundations thereof I destroyed. I made its destruction more complete than that by a flood. That in days to come, the site of that city, and (its) temples and gods, might not be remembered, I completely blotted it out with (floods) of water and made it like a meadow.”26

Esarhaddon (681-669)

Esarhaddon became king as a younger brother and had to fight for the throne.27 It would appear that Manasseh, Hezekiah’s son, became a vassal of Assyria. Esarhaddon says, “Ba’lu, king of Tyre, Manasseh, king of Judah…together 22 kings of Hatti, the seashore and the islands; all these I sent out and made them transport under terrible difficulties, to Nineveh, the town (where I exercise) my rulership, as building material for my palace: big logs, etc.”28 Ashurbanipal (668-633) also lists Manasseh as a supporter in his Egyptian war: “Ba’al, king of Tyre, Manasseh, king of Judah…servants who belong to me, brought heavy gifts to me and kissed my feet. I made these kings accompany my army over the land…”29

This vassalage would also include submission to the Assyrian deities which Manasseh did with a passion. His was a long and wicked rule. The Chronicler says, “Therefore, the Lord brought upon them the commanders of the army of the king of Assyria, who took Manasseh with hooks and bound him with fetters of bronze and brought him to Babylon. And when he was in distress he entreated the favor of the Lord his God and humbled himself greatly before the God of his fathers. He prayed to him, and God received his entreaty and heard his supplication and brought him again to Jerusalem into his kingdom. Then Manasseh knew that the Lord was God” (2 Chron. 33:11-13).

Even though this is not recorded in Kings nor in the Assyrian records, as Bright says, “it is quite reasonable to suppose that it rests on a historical basispossibly in connection with the revolt of Shamash-shum-ukin (652-648)…Whether Manasseh was found innocent or was pardoned, as the Egyptian prince Neco had been, we cannot say. But it is quite possible that he was no more loyal to Assyria than he had to be, and would gladly have asserted his independence had he been able.”30

Esarhaddon invaded Egypt in 674 and was defeated. He invaded again in 671 and defeated Taharqa. “From the town of Ishhupri as far as Memphis, his royal residence, a distance of 15 days (march), I fought daily, without interruption, very bloody battles against Tirhakha, king of Egypt and Ethiopia, the one accursed by all the great gods. Five times I hit him with the point of (my) arrows (inflicting) wounds (from which he should) not recover, and (then) I led [sic] siege to Memphis, his royal residence, and conquered it in half a day by means of mines, breaches and assault ladders.”31 He set out again in 669 but died on the way.

Ashurbanipal (669-631).

This king may well have been trained as a scholar rather than a king because of his constant boasts about his education. It is that which has produced so much archaeologically, for he gathered the greatest collection of texts known from that period of history. At his palace in Nineveh were found thousands of tablets containing information from many areas of study. It was here that the Gilgamesh epic was found.

Ashurbanipal defeated Egypt and forced a number of kings, including Manasseh, “to accompany my army over the land” in his attack on Egypt. The Assyrians now ruled Egypt completely. Taharqa fled to his Nubian capital, Napata, and Assyria appointed Necho I as a subordinate king. Taharqa’s son Tantamani returned north and reconquered Egypt. Ashurbanipal sent his army back (663) and again routed the Nubians, driving Tantamani back to Napata. They looted Thebes completely (Nahum refers to the fate of No-Amun or Thebes in 3:8-10).

The letter in Ezra 4:10 says, “then wrote Rehum the commander and Shimshaia the scribe and the rest of their colleagues, the judges and the lesser governors, the officials, the secretaries, the men of Erech, the Babylonians, the men of Susa, that is the Elamites, and the rest of the nations which the great and honorable Osnappar deported and settled in the city of Samaria, and in the rest of the region beyond the River” (Ezra 4:9-10). Most commentators identify this Osnappar with Ashurbanipal.32 This deportation is otherwise unknown, but his defeat of 22 kings in the west is known.33 Furthermore, Isaiah 7:8 mentions a mysterious 65 year period during which “Ephraim will be shattered, so that it is no longer a people.” If the Syro-Ephraimite attack was in 735/34, then 65 years would bring us to 670/69 or the first year of Ashurbanipal.

“It is quite possible that Judah suffered during the Assyria invasions of Egypt (675, 671, 667 and 663 B.C.), and, on the strength of Is. vii, 8, it has often been calculated that there was some fresh deportation of Ephraim, perhaps in connection with a pro-Egyptian revolt. Be that as it may, for some reason Manasseh was carried off in chains to Babylon (2 Chron. xxxiii, 11), and fresh colonists settled in Samaria by Esarhaddon and, apparently, by Ashurbanipal (Ezr. iv, 2, 10). Necho of Egypt, who had been removed by Ashurbanipal, had been sent back with every mark of royal favour--it was Assyrian policy to conciliate the Deltaand therefore the Chronicler’s statement that Manasseh was captured and afterwards allowed to return is not to be regarded as incredible. It is only natural that before Manasseh returned he must have been able to assure Assyria of his loyalty.”34

Continued revolt by the Egyptian princes apparently convinced Ashurbanipal that he could not hold Egypt without larger garrisons than he could spare. Consequently, he quietly let go of Egypt and, for all practical purposes, Egypt and Assyria became allies.

Ashurbanipal ruled from Nineveh, but his brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, had been installed in Babylon by Esarhaddon. This diarchite proved to be a source of friction. No one could rule Babylon without the approval of the Chaldeans who had infiltrated the cities and exercised much control. Shamash-shum-ukin decided to rebel against his brother, and a protracted civil war followed. It was concluded by a siege of Babylon resulting in the suicide of Shamash-shum-ukin. Ashurbanipal installed another Assyrian governor in Babylon and continued the previous practice.

In spite of the strength of Ashurbanipal’s rule, his latter days were beset by physical illness and disruption in his family. His son and successor, Ashur-etil-ilani (631-619), had to fight for the throne. This struggle was long and left Assyria weak. In the south, Nabopolassar, the Chaldean prince, broke away from Assyria and began hostilities. Palestine, under Josiah, broke away from Assyria during this time. Josiah was able to extend his reform to the north and may even have established some political control as well.

Sin-shar-ishkun succeeded Ashur-etil-ilani. He was a good ruler, but he faced the combined armies of the Chaldeans and the Medes and his army had been weakened in the previous two decades. Nabopolassar was able to defeat the Assyrians in 616. Cyaxares, the Median general, marched on the Assyrians in 614 sacked the ancient Assyrian capital of Ashur for the first time in Assyrian history. Nabopolassar joined in the looting, and the Chaldeans and Medes became fast allies.

Sin-shar-ishkun depended on the Scythians to help him, but they betrayed him, perhaps in the expectation of great booty. As a result, Nineveh fell in 612 to the combined forces of the Medes, Babylonians, and Scythians. The Babylonian chronicle says, “On that day Sin-sar-iskun, the Assyrian king…The great spoil of the city and temple they carried off and [turned] the city into a ruin-mound and heaps of debri[s…”35

Nahum (3:8-15) says, “Are you better than No-amon [Thebes], which was situated by the waters of the Nile, with water surrounding her, whose rampart was the sea, whose wall consisted of the sea? Ethiopia was her might, and Egypt too without limits, Put and Lubim were among her helpers. Yet she became an exile, she went into captivity; also her small children were dashed to pieces at the head of every street; they cast lots for her honorable men, and all her great men were bound with fetters. You too will become drunk, you will be hidden. You too will search for a refuge from the enemy. All your fortifications are fig trees with ripe fruit--when shaken, they fall into the eater’s mouth. Behold, your people are women in your midst! The gates of your land are opened wide to your enemies; Fire consumes your gate bars. Draw for yourself water for the siege! Strengthen your fortifications! Go into the clay and tread the mortar! Take hold of the brick mold! There fire will consume you, the sword will cut you down; it will consume you as the locust does.”

The Assyrians refused to quit. Under Ashur-ubalit, perhaps a brother of Ashurbanipal, they regrouped at Haran. Nabopolassar was unwilling to attack Haran alone. He was finally joined by the Medes and Scythians once more. Egypt had come to Assyria’s side and joined with them outside the city of Haran. Haran was captured by Babylon and sacked. The Assyrians and Egyptians were defeated in 609, but the struggle against Egypt continued until 605 when Necho was defeated at Carchemish. Nebuchadnezzar probably set up his command post in Riblah to which Jehoiakim would have come to offer fealty. Daniel and others were taken hostage at that time. Jeremiah (46:1-2) mentions the defeat of Necho at Carchemish in 605.

Assyria was completely despoiled and enslaved. Very little evidence of Assyrian culture is left from that time on.36

1See Finegan, Light from the Ancient Past.

2CAH 2,1:178 says that Shamshi-Adad died in the tenth year of Hammurabi (1792-1750).

3There was pressure from the young and powerful Aramean states that damaged Assyria until the new kingdom (CAH 3:5-6).

4See M. E. L. Mallowan, “Nimrud” in AOTS, 57-72.

5ANET, pp. 278-79. Note Ahab in the underlined section.

6So Olmstead, History of Assyria, p. 137, and Sidney Smith, CAH 3:22.

7The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 B.C.).

8See Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings.

9See ANEP, 351-55, ANET, pp. 280.

10ANET, p. 282.

11See 2 Kings 14:22-29.

12Tadmor, “Azarijau of Yaudi” Scripta Hierosolymitana 8 (1961): 232-271. However, Israelite and Judaean History, Old Testament Library, edited by John H. Hayes and J. Maxwell Miller. London: SCM Press, 1977 says, “Recently, Na’aman [Nadav Na’aman. “Sennacherib’s ‘Letter to God’ on His Campaign to Judah,” BASOR CCXIV (1974) 25-39] has argued that the fragment presumably mentioning Azriau king of Yaudi actually belongs to the time of Sennacherib and refers not to Azariah but to Hezekiah. In Tiglath-Pileser’s annals there are two references to an Azariah (in line 123 as Az-ri-a-[u] and in line 131 as Az-r-ja-a-í) but neither of these make any reference to his country. Thus the Azriau of Tiglath-pileser’s annals and Azariah of the Bible should be regarded as two different individuals. Azriau’s country cannot, at the present, be determined.” Na’aman separates the country (Yaudi) from the name Azriau (p. 36). Also p. 28 on line 5 where the original transcription was “[I]zri-ja-u mat Ja-u-di” he reads “ina birit misrija u mat Jaudi.” However, Kitchen, OROT, p. 18, is less dogmatic. He says “Hence we cannot certainly assert that this Azriau (without a named territory!) is Azariah of Judah; the matter remains open and undecided for the present and probably unlikely.” See Also CAH, 3:35-36.

13ANET, 282,83.

14CAH 3:32 says the Pul may be the original name or the one used in Babylon.

15ANET, p. 283-84.

16Albright argues that this was a descendent of David through an east Jordan woman (W. F. Albright, “The Son of Tabeel [Isaiah 7:6],” BASOR 140 [1955] 34-35).

17See E. J. Young, Isaiah in NICOT, loc. cit.

18ANET, pp. 283-84.

19ANET, pp. 284-85.

20Light from the Ancient Past, p. 210. But see Thiele, Mysterious Numbers, p. 168, who argues that Sargon merely claimed credit, but was only involved in later suppression.

21ANET, p. 287.

22ANET, pp. 287‑288.

23See discussion under Taharqa of Egypt, p. 115.

24Seth Erlandsson, Burden of Babylon, pp. 65-108.

25For an excellent discussion, see D. D. Luckenbill, The Annals of Sennacherib, pp. 9-19

26Luckenbill, Annals of Sennacherib, p. 17.

27ANET, pp. 289-90.

28ANET, p. 291.

29ANET, p. 294.

30J. Bright, History of Israel, p. 290. See also p. 122.

31ANET, p. 293.

32Cf. Williamson, Ezra/Nehemiah in the Word Commentary, p. 55 where he says, “The confusion of l and r at the end of the word may reflect Persian influence, but the loss of medial rb cannot be explained on such philological grounds.”

33ANET, p. 294.

34S.A. Cook, CAH 3:393.

35D. J. Wiseman, Chronicles of Chaldaean Kings (626-556 B.C.) in the British Museum, p. 61; see his discussion pp. 15-16.

36This discussion on the last days of Assyria comes from S. Smith, CAH 3:113-131 and Wiseman, Chronicles, pp. 5-27. See also M. Noth, The Old Testament World, Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia, W. W. Hallo, “From Qarqar to Carchemish.” BAR #2, and Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, pp. 264-85.

Related Topics: Archaeology, History

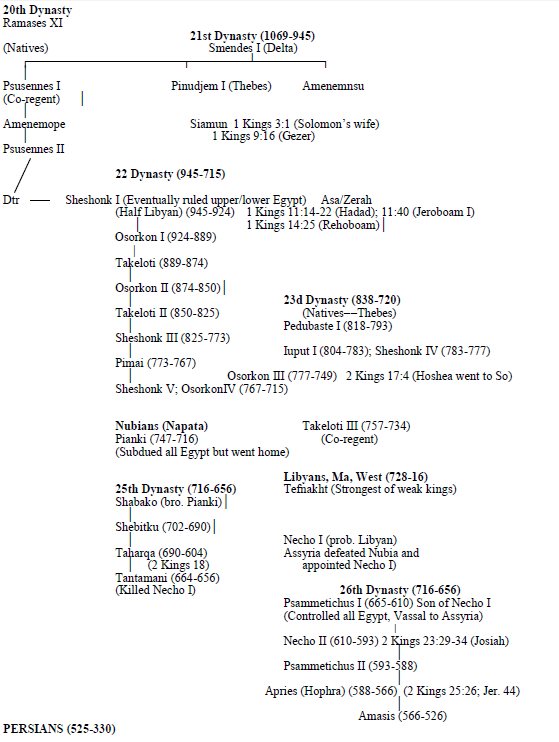

17. Israel/Judah And Egypt 1000 B.C. To 500 B.C.

Related MediaThe Twenty-first Dynasty

(“Post-Imperial” Epoch)1

Smendes I (c. 1069-1043) (Saul: 1051-1011)

He was the powerful ruler of the north under Ramases XI. When the latter died without heirs, he became the pharaoh.

Pinudjem I (c. 1053-1010)

He became co-regent in Thebes during the final decade of Smendes I’s life. The reasons are not clear. When Smendes died Pinudjem was old and Nefferkare Amenemnsu became king in Tanis (1043-1039).

Amenemnsu’s half-brother, Psusennes I, also a son of Smendes, became king (1039-991 B.C.) while Pinudjem I was still alive. He was in the prime of life and very active. (David: 1011-970)

Amenemope (993-984 B.C.),