1. Joshua

Related MediaI. Introductory matters.

A. The man Joshua.

With Joshua, we begin what the Hebrew sages called the “Former Prophets.” This section in the Hebrew Bible goes from Joshua through Second Kings. Joshua, like Moses, was considered a prophet. “The designation indicates a rabbinic concern with the special character of these ‘histories’ which put them together in a special group immediately following the Torah”1

Joshua served with Moses as his attendant from his youth (Num 11:28). He led the attack on the Amalekites (Exodus 17) and climbed the “mount of God” with Moses when God revealed Himself (Exodus 24). He was one of the twelve men who went in to reconnoiter the land, and with Caleb, the only one to insist on taking the land in spite of the dangers (Numbers 13). For this act, he and Caleb were accorded the privilege of living through the 40 years of wanderings and to enter the land.

Num 27:18-23 relates the choice of Joshua as Moses’ successor.2 This is the strongest language possible to indicate that Joshua was anointed by God to hold the same position of leadership as Moses. He is therefore also considered a prophet as was Moses (though not with his stature—Deut 34:10). Deuteronomy 3 indicates that Joshua, not Moses will lead the people into the land. And, finally, Joshua is recommissioned in Deut 31:14-23. The last chapter of Deuteronomy closes Moses’ life and prepares the reader for the Book of Joshua and the feats of Joshua: “Now Joshua the son of Nun was filled with the spirit of wisdom, for Moses had laid his hands on him; and the sons of Israel listened to him and did as the Lord had commanded Moses” (Deut 34:9).

B. The study of Joshua today.

1. The date of the Exodus and entry into the land.

The date of the Exodus is set out in 1 Kings 6:1. The building of the temple of Solomon was begun in the 480th year of the Exodus from Egypt. This means that the Exodus took place in 1441 (some variance must be allowed for the chronology of the kings of Israel), and the entrance to the land would have been around 1400. There was a time when this was the consensus view of Bible students.

In modern times, under W. F. Albright and his students in particular, there was an argument for a “late date” of the Exodus. This was usually placed somewhere in the 13th century (1250, 1225) based on such things as the name of Rameses (presumed to be the II who had a long reign in the 13th century) in Exod 1:11.3 Now critical scholarship does not believe there was anything like the biblical account.

2. The minimalist/maximalist debate.

There is an ongoing debate today among Old Testament scholars tagged “between the minimalists and the maximalists.” Minimalists are those who argue for little or no historicity of the Bible before the exilic period, while maximalists argue for general historicity. Bearing in mind that even the maximalists do not believe the Bible represents true history. In light of this ongoing discussion, I am reproducing here an article from the Biblical Archaeology Society called the Rise of Ancient Israel. It does not represent the Bible believing conservatives, but it does set forth the issues. The article is written by Herschel Shanks, editor, who is also Jewish.

“Bryant Wood has recently reexamined the archaeological evidence relating to the destruction of Jericho.4 There was a destruction at Jericho. All archaeologists agree on this. But when did it occur? The most recent and most famous excavator of Jericho, the British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon, dated this destruction to the Middle Bronze Age—after which the site was abandoned. Thus, she said, there was no city here for Joshua to conquer at the end of the Late Bronze Age. This view has been widely accepted and has posed a major problem for the conquest model. In his careful reexamination of the archaeological data, not only from Kenyon’s excavations but also from earlier excavations, Wood has shown that this destruction at Jericho occurred in uncanny detail just as the Bible describes it. There was a strong wall there, just as the Bible says. And the wall even came tumbling down, according to the archaeological evidence. Actually, there were two walls around the city—the main city wall at the top of the tell and a revetment wall lower down. Outside this revetment wall, Kenyon found piles of red mud bricks that had fallen from the city wall at the top of the tell and then tumbled down the slope, piling up at the base of the revetment wall. (Or the bricks could have been on top of the revetment wall and tumbled down from there; the difference is insignificant. The fact is they came together in a heap outside the revetment wall). The amount of bricks piled up there was enough for a wall 6.5 feet wide and 12 feet high.

“These collapsed bricks then formed a kind of ramp that an invading army could have used to go up into the city. And sure enough, the Bible tells us that the Israelites who encircled the city ‘went up into the city, every man straight before him’ (Joshua 6:20).

“Moreover, the wall could have tumbled as a result of an earthquake. Earthquake activity is well known in this area: Jericho sits right in the Great Rift on the edge of a tectonic plate.

“Kenyon found that the city was destroyed in a fiery conflagration: the walls and floors were blackened or reddened by fire. But, she adds, ‘the collapse of the walls of the eastern rooms seems to have taken place before they were affected by the fire.’ This was the sequence of events in the biblical account of Jericho’s conquest: The walls fell down and then the Israelites put the city to the torch.

“The archaeologists also found heaps of burnt grain in the houses—more grain than has ever been found in any excavation in what was ancient Israel. This indicates two things: First, the victory of the invaders must have been a swift one, rather than the customary siege that would attempt to starve out the inhabitants (the biblical victory was of course swift). Second, the presence of so much grain indicates that the city must have been destroyed in the spring, shortly after the harvest. That is when the Bible says the attack occurred. There is another strange thing about the presence of so much grain. A successful invading army could be expected to plunder the grain before setting the city on fire. But the army that conquered Jericho inexplicably did not do this. The Bible tells us that the Lord commanded that everything from Jericho was to be destroyed; they were to take no plunder.

“One last item, the Bible tells us that the attacking Israelites were able to ford the Jordan easily because the river stopped flowing for them; the water above Jericho stood up in a heap (Joshua 3:16). This has actually happened on several occasions in modern times. At this point the Jordan is not a mighty stream. It has been stopped up by mud slides and by material that fell into it in connection with earthquakes. The water actually ceased flowing for between 16 hours and two days, as recorded in 1927, 1906, 1834 and on three even earlier occasions.

“So what do we make of all this?

“One way to deal with it is to say that the Israelites somehow had a memory of this early destruction of Jericho and incorporated it into their own theologically oriented history, even though it was not actually the Israelites that did the conquering.

“Another way is to attribute the destruction of Jericho to the Israelites. This requires either that you move the Israelite conquest back to the Middle Bronze Age or that you reinterpret the archaeological evidence so that you attribute the destruction to the Late Bronze Age instead of to the Middle Bronze Age. Both of these things have been attempted, although most scholars reject these efforts to attribute Jericho’s destruction to the Israelites.

“This brings me to the question of dating, about which I will say only a few words. Most archaeologists are agreed that if there is archaeological evidence for the emergence of Israel in Canaan, it must be at the beginning of the Iron Age, about 1200 B.C.E.

“Yet there is also evidence that there was an important people called Israel living in Canaan as early as the late 13th century B.C.E. I’m referring to the famous Merenptah Stele found in Thebes at the end of the last century. The Merenptah Stele is a black granite slab over 7.5 feet high, covered with hieroglyphic writing. Mainly it recounts the exploits of Pharaoh Merenptah during his Libyan campaign, but at the end he also recalls his earlier victories in a military campaign in Canaan.

“Now there are two universally agreed facts about this stele. One is that it dates to 1207 B.C.E. Second, it mentions Israel in connection with this earlier campaign in Canaan. There in hieroglyphic writing is the earliest extra-biblical mention of Israel. This is what it says:

‘Canaan has been plundered into every sort of woe;

Ashkelon has been overcome;

Gezer has been captured.

Yanoam was made nonexistent;

Israel is laid waste; his seed is not.’

“Now there are a couple of things I want to say about this mention of Israel.

“This is not just a mention in a deed or a contract that may have reference to a small village or even less. This reference to Israel shows that the most powerful man in the world, the pharaoh of Egypt, was aware of Israel. Not only was he aware of Israel—he boasts that one of the most important achievements of his reign was to defeat Israel. Of course, he exaggerates when he says that Israel’s seed is not. We know that even today, 3,200 years later, that seed is still growing and thriving. But that is beside the point. The fact is that in 1212 B.C.E. (the campaign was five years before the inscription), Israel must already have been a military force to be reckoned with. And this is right in that transition period between the Late Bronze Age and Iron I.

“The next point I want to make about the Merenptah Stele, which is sometimes also called the Israel Stele, requires us to talk a little about hieroglyphics. In hieroglyphic writing there are some signs that are not pronounced; they indicate the kind of word to which they are attached. The unpronounced signs are called deter-minatives. So, in the quotation I read to you from the Merenptah Stele, where the pharaoh was victorious over four entities in Canaan, each entity, in addition to the signs indicating how the word is pronounced, also has attached to it a determinative that tells us what kind of word it is. Attached to three of the four entities—Ashkelon, Gezer and Yanoam—is a determinative that tells us that they are cities. The determinative attached to Canaan, which introduces the set of four, is the determinative for a foreign land. The determinative attached to Israel, however, is for a people. In other words, in 1207 B.C.E. Israel was a people in Canaan important enough not only to be known to pharaoh, but important enough for him to boast that he defeated them militarily.

“The Merenptah Stele is obviously a very important piece of evidence in connection with the current debate about the rise of Israel.

“If Israel was already such a force in Canaan in 1212 B.C.E., then Israel must have been established there for some time. Those who would like to push back the date for Israel’s entry into Canaan, stress this aspect of the Merenptah Stele.

“On the other hand, those who say that Israel’s existence only begins with the monarchy have to deal with this troubling bit of evidence. I often wonder what would happen if we didn’t have this fortuitously preserved find. I’m almost certain that those scholars who insist that Israel didn’t exist before the monarchy and who tell us that there is no premonarchical history to be gleaned from the premonarchical accounts in the Bible would carry the day. The biblical tales we would convincingly be told are mere bobbe-mysehs, grandmothers’ tales. How do these scholars deal with the Merenptah Stele, since it indubitably does exist? They say that Israel refers to something else. What that something else is, is not clear. I certainly can understand that the numbers in the Bible are exaggerated. And there is evidence even in the Bible that there were not always 12 tribes in a league together. But the Merenptah Stele does date from the time when the nation and people that became Israel were aborning, were in the early stages of their development.

“A final point about the Merenptah Stele and its significance. Very recently, some reliefs on a temple at Karnak have been identified as illustrations of this famous passage from the Merenptah Stele.5 One panel of reliefs represents Ashkelon; other panels appear to represent the other Canaanite cities mentioned in the Merenptah Stele. Unfortunately, there is still a dispute as to which panel or panels pictures the Israelites. In one panel that is a contender, the Israelites have long togas or skirts, just like the other Canaanites. So it is argued that this supports the contention that Israel emerged out of Canaanite society. In another panel which supposedly represents the Israelites, they have short skirts, quite unlike the Canaanites, so this supports the argument that the Israelites entered Canaan from outside the land.6

“If they did come from outside the land, then this raises the question of where they came from. In short, was there really an Exodus? For the Exodus, we don’t have a Merenptah Stele; we don’t have any evidence that the Israelites as such were in Egypt.

“What we do have is evidence of Canaanite pottery in Egypt, and we also have evidence that Canaanite traders would come down to Egypt just like Jacob and his sons. A very famous picture from a tomb at Beni Hasan in Egypt pictures some merchants from Asia coming down to Egypt to do business. This tomb is beautifully preserved in cliffs overlooking the Nile about halfway between Cairo and Luxor.

“Finally, there is evidence concerning a strange people known as the Hyksos. That’s the name by which we know them, but that’s not what they called themselves. The Hyksos were a people from Asia—Canaan—who came down to Egypt and ultimately became the rulers of Egypt for two Egyptian dynasties. Ultimately, they were expelled by the Egyptians, who chased them back into Canaan. Obviously, the rise of the Hyksos in Egypt seems to have echoes in the biblical story of Joseph. The expulsion of the Hyksos seems to be some kind of Exodus in reverse. Instead of fleeing, they were kicked out. Whether there is any connection between the Hyksos and the biblical accounts I will leave to my good friend Baruch Halpern. In the meantime, you can ask me a few questions, but not too many because what I have tried to do is simply give you a little background, some of the framework and parameters of the extraordinarily vigorous debates that are going on in the academy. From the other speakers, we are going to go out into the jungle. These are the people who are exploring beyond the point where I have taken you, developing the lines of thought that will dominate the discussion in the years to come.

“The Bible is historically true in the details, whether we would accept it as historically accurate by modern historians’ standards, by modern historiography. That is not to denigrate the richness of the biblical text. I think many people who do not accept the literal reading of the Bible find it a very enriching and inspiring and even Godly document, without the necessity of it being literally true in every detail. This whole discussion proceeds on the basis that we will examine the Bible in this way. What I have tried to do is to summarize some of the problems in the biblical text and to describe some of the ways scholars have dealt with them.”7

3. The issue of conflicting statements in Joshua and Judges.

Josh 11:23 states that Joshua took the whole land according to all that the Lord had spoken to Moses. In 11:15-22 it is clearly stated that all the land was conquered and conquered completely. Yet, Judges 1-2 indicate that many people were not conquered. How can these be reconciled? First the Book of Joshua itself indicates that not everyone was routed (Josh 13:1-7). As to the broad generalizations, Kitchen’s remarks are apropos.

“Thus, to sum up, the book of Joshua in reality simply records the Hebrew entry into Canaan, their base camp at Gilgal by the Jordan, their initial raids (without occupation!) against local rulers and subjects in south and north Canaan, followed by localized occupation (a) north from Gilgal as far as Shechem and Tirzah and (b) south to Hebron/Debir, and very little more. This is not the sweeping, instant conquest-with-occupation that some hasty scholars would foist upon the text of Joshua, without any factual justification. Insofar as only Jericho, Ai, and Hazor were explicitly allowed to have been burned into nonoccupation, it is also pointless going looking for extensive conflagration level as at any other Late Bronze sites (of any phase) to identify them with any Israelite impact. Onto this initial picture Judges follows directly and easily, with no inherent contradiction: it contradicts only the bogus and superficial construction that some modern commentators have willfully thrust upon the biblical text of Joshua without adequate reason. The fact is that biblical scholars have allowed themselves to be swept away by the upbeat, rhetorical element present in Joshua, a persistent feature of most war reports in ancient Near Eastern sources that they are not accustomed to understand and properly handle.8

“The sweeping statements in Joshua (‘he subdued the whole region,’ or ‘wholly destroyed all who breathed’) are rhetorical summations, practiced by all the ancients. In 10:20 we learn that Joshua and his forces massively slew their foes ‘until they were finished off’ (‘ad-tummam), but in the same breath the text states that ‘the remnant that survived got away into their defended towns.’ Thus the absolute wording is immediately qualified by exceptions.”9

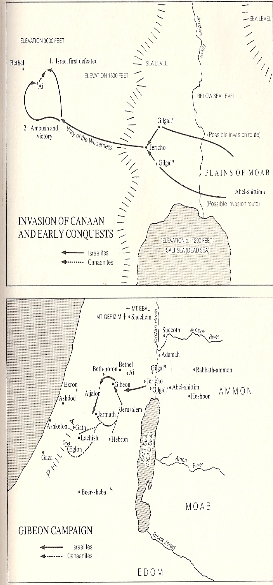

II. Entering the Land (1:1—5:15)

A. Covenant Reaffirmation (1:1-18)

1. We learn from Deut 34:9 that Joshua was filled with the spirit of wisdom and that Moses had “laid his hands on him” and the people responded accordingly. Thus, the Book of Joshua opens with a charge to this man who held the awesome responsibility of succeeding Moses and leading the people into the land (1:1).

2. God’s charge to Joshua gives him his instruction and the extent of the land God was promising to Israel. These boundaries are quite extensive (1:2-4).

3. God then provides Joshua a promise. “No man will be able to stand before you all the days of your life.” This promise obviously has conditions. When Israel sinned, they were unable to defeat the people of Ai. So, obviously, the exceptions must be understood (1:5-6).

4. God then admonishes Joshua to be strong, and to do all the law of Moses. Verse 8 is a wonderful verse that all believers should memorize and practice (1:7-9).

5. Joshua then acts decisively and orders his various officers to prepare the people to move in three days to cross the Jordan and possess the land (1:10-12).

6. The Reubenites and Gadites will always be an exception to be dealt with. We learn early that the people of Israel had both a centrifugal and a centripetal force. The force that tended to fling them apart was the tribal structure. The force that tended to keep them together was the central sanctuary and the worship of Yahweh. Thus, Joshua makes sure that they will not peel off from the rest of Israel and form their own community. They must come and fight with their brethren (1:12-18).

Excursus on the Destruction of the Canaanites

Albright gives an apologetic for the destruction of the Canaanites. This is quite a strong contrast to a prominent Methodist bishop of a several years ago who referred to the God of the Old Testament as a Bully. Albright argues first that contemporary “civilizations” have little right to sit in judgment on others with regard to total warfare. Secondly, he says, “It was fortunate for the future of monotheism that the Israelites of the Conquest were a wild folk, endowed with primitive energy and ruthless will to exist, since the resulting decimation of the Canaanites prevented the complete fusion of the two kindred folk which would almost inevitably have depressed Yahwistic standards to a point where recovery was impossible.”10

G. Ernest Wright also says, “War is a miserable business in a world of men who live in rebellion against the conditions of their creation. Yet God as Suzerain is not defeated. He uses people as they are, to further his own, often mysterious ends. Hence by implication, we must say that God’s use of Israel and her early institution of Holy War does not invest either war or Israel with sanctity or righteousness. On the contrary both are evil; yet God used Israel as she was for his own purposes. And among the results was the creation of the seedbed for Judaism, Jesus Christ, and the Christian movement.”11

End Excursus

B. Spies Sent Out (2:1-24)

1. The need to reconnoiter the land (2:1-7).

Just as Moses had sent out twelve spies prior to entering the land, so Joshua sends out two men to check out Jericho.

They go the Rahab’s house. The Scriptures refer to her consistently as a harlot, and we should not cavil at that. People are also concerned about her “lie,” but why should we expect otherwise? She is a Canaanite woman in need of redemption.

The reference to a “king” in Jericho is the common referent to leaders of city states in Canaan as borne out by the Amarna Tablets.12

Rahab is held up as a woman of faith in Hebrews 11:31 and she is included in the genealogy of Matthew. She certainly demonstrated faith that others did not share, for she believed that God had given the land to the Israelites.

2. Rahab’s faith and courageous action (2:8-14).

The writer of Joshua wants us to understand God’s work on behalf of His people. Consequently, he includes this speech of the woman in which she acknowledges: a) The fear of the Israelites is on everyone, b) all those who have met the Israelites have “melted” before them, c) the Lord opened the Red Sea, and d) the defeat of the two Amorite kings. This leads to the peak of her testimony: “Yahweh your God, He is God in heaven above and on earth beneath.” In light of all this, she begs them to preserve her life. The men agree to do so and remind us again that the time will come “when Yahweh gives us the land” a major theme in this book.

3. The oath of the spies (2:15-21).

The men promise her that if she will follow their instructions, she and her family will be delivered.13 She must hang a scarlet cord from her window, indicating which house is hers; none of her family may make themselves vulnerable by going outside the confines of her house; and she must not tell anything she knows to the authorities.

4. The conclusion of their activities (2:22-24).

The spies return home and recount their experiences. They also provide the testimony of the theme of the book, “Surely the Lord has given all the land into our hands, and all the inhabitants of the land, moreover, have melted away before us.” This reconnoitering of the land was unnecessary in light of later instructions about how the city would be divinely destroyed, but Joshua did not know that yet.

C. Crossing the Jordan (3:1-17)

1. The Importance of the ark (3:1-4).

The ark was ever the symbol of God’s holy presence. Here God is indicating that He alone will lead his people to victory. The people are to keep a respectful distance lest they violate the holy presence. This is much like God’s revelation from Mt. Sinai.

2. The importance of ritual (3:5-6).

Consecrating oneself involved abstaining from certain activities (such as sexual intercourse), as a sign that they had set themselves com-pletely apart to God.

3. The validation of Joshua’s ministry (3:7-13).

It was important that the people recognize and submit to the authority of Joshua as God’s consecrated leader. This action also validated the promise that God would dispossess the people from the land. Twelve men are selected (one from each tribe, indicating the whole house of Israel). Their task will be taken up in chapter 4.

4. The miracle of the stopped waters (3:14-17).

The deliberate identification of Joshua’s ministry with that of Moses is carried on in the miracle of the Jordan. This is compared to the miracle of the Red Sea crossing by Moses (4:23). Further validation of Joshua’s ministry and leadership is thus provided.

Garstang explains the miracle in natural terms: “It so happens that the river near this ford is liable to be blocked at intervals by great landslides. Several of these are on record. The earliest occurrence dates from A.D. 1266 when the Sultan Bibars ordered a bridge to be built across the Jordan in the neighbourhood of Damieh. The task was found to be difficult owing to the rise of the waters. But in the night preceding the 8th December, 1267, a lofty mound, which overlooked the river on the west, fell into it and dammed it up, so that the water of the river ceased to flow and none remained in its bed. The waters spread over the valley above the dam, and none flowed down the bed for some sixteen hours.”14

D. The Memorial Stones from the Jordan (4:1-24)

1. The Lord directs Joshua to get the stones (4:1-3).

This passage is anticipated by 3:12. There is a three-step process: the Lord commands Joshua, Joshua commands the men, and the men carry out the act.

2. Joshua passes on the command to twelve men (4:4-7).

The Old Testament is replete with the concept of remembering the great acts of Yahweh. These stones become part of that catena of reminders.

3. The twelve men carry out their duty and the crossing is completed (4:8-18).

The men took up (wayise’u וַיִּשְׂאוּ) the stones, carried them out, and deposited them at their encampment (N.B. it does not say they set up a memorial. That will come later at Gilgal). The real problem comes at verse 9. This is universally understood as a second memorial set up by Joshua (without divine orders to do so) in the midst of the Jordan. Some argue that the place they were set up was where the priests stood, i.e., at the edge of the waters. So, they would not have been washed away easily.

I wonder if verse 9 should not be understood differently. First of all, the rest of the sequence (verses 1, 3, 4, 5, 8) are all narrative tenses (we call these preterites). Verse 9 uses a construction that interrupts the chain, and in this case, provides a conclusion to the entire sequence. It would be unusual to have this conclusion include a new altar in the midst of the Jordan.

Verse 3 says the stones are to come from the midst of the Jordan (mitok hayarden מִתּוֹךְ הַיַּרְדֵּן). Verse 5 says the men are to cross to the midst of the Jordan (el tok hayarden הַיַּרְדֵּן אֶל תּוֹךְ). Verse 8 says the men took up the stones from the midst of the Jordan (mitok hayarden מִתּוֹךְ הַיַּרְדֵּן). The concluding verse 9 says that Joshua raised up these stones (this could mean simply that he took them up,15 but it probably means that he erected them [as a memorial]). I wonder if this verse does not refer to what Joshua did later at Gilgal (same use of the hiphil). The only problem with this idea is that the Hebrew says clearly that he erected the stones in the midst of the Jordan. However, the Hebrew labials “m” and “b” are often confused. With the “m” here, it would mean the stones which were from the Jordan. The translation would then read, “So Joshua erected the twelve stones [which had come] from the midst of the Jordan, the place of the standing of the feet of the priests.” This would anticipate 4:20 just as 3:12 anticipates all of chapter 4.

The priests remained standing in the Jordan until the crossing was completed.16 The author wants us to understand that all God’s good word had been carried out (4:10). Furthermore, the tribes who had chosen to settle on the eastern side of the Jordan crossed over—the Reubenites, Gadites, and half the tribe of Manasseh. Finally, the Lord exalted Joshua as he had promised in the eyes of the people, i.e., the miraculous crossing demonstrated that the Lord was with Joshua as He had been with Moses.

The priests then (at the Lord’s command) walked on across the Jordan and the waters returned to their place (4:15-18).

4. The great testimonial (4:19-24).

The Israelites came out of the water on the tenth day of Nisan (the first of the Hebrew religious months). This date will be very important in the next chapter. Now we have the official erection of the twelve stones as a cairn of remembrance (anticipated in 4:9). Joshua set up the cairn in Gilgal, a place that will hold great importance for Israel in the days to come. Here Joshua repeats the litany of God’s provision for His people in bringing them out of Egypt and now into the promised land. Again, we are reminded that it is not Joshua or the people who are at the center of history, but Yahweh God.

E. A New Beginning (5:1-15)

The chapter begins with the note that the inhabitants of the land had heard about the miraculous crossing of the Jordan river, and, as a result, their hearts “melted.” The Israelites, under God’s direction are about to embark on a new enterprise. This requires a reevaluation of where they are spiritually and preparation to make this new move. The first reevaluation concerns circumcision.

1. New Circumcision (5:1-9).

Circumcision, of course, is the sign of the covenant God made with Abraham. It was therefore a necessary ritual to keep reminding the people of who they were under God’s covenant, made with Abraham and renewed at Sinai. Consequently, prior to entering the land, all those who had been born in the wilderness had to be circumcised.17 The place name Gibath-haaraloth (גִּבְעַת הָעֲרָלוֹת) may be a geographical location, or a reference to the circumcision itself. It means literally “hill” or “heap” of the “foreskins.” Verse nine has a play on the name Gilgal. Hebrew words with “gil” or “gal” as a component have something to do with round: a wheel (Gilgal), a lake (Galilee), a region (Gilead), or a head (Golgotha), for instance. The verb also means to go around in circles or to dance. The Hebrew verb “to roll away” comes from “gallothi.” Since it has a similar sound to Gilgal, the Lord relates the two. The site of Gilgal is to remind them that Yahweh has rolled away the reproach of Egypt (the embarrassment and shame of their enslavement). Now they are ready to partake of the Passover.

2. New Passover (5:10).

This important ritual feast originated in God’s deliverance of His people from the bondage of Egypt. Now the combination of circumcision and Passover indicate that Joshua is truly leading God’s people into their rest (Heb 4:8). Unfortunately, the people did not wholly follow the Lord and so did not actually enter the rest God had designed for them. So, a new rest in Christ will come about.

3. New Food (5:11-12).

God’s miraculous provision of food in the wilderness must also cease. The wilderness wanderings are over, and a new food is in the offing. Consequently, the people eat of the produce of the land on that day and the Manna ceased. Now they are ready to go, and divine direction is about to take place.18

4. New Revelation of Joshua (5:13-15).

One of the most intriguing passages in the Book of Joshua occurs here. The mysterious person called the prince or leader of Yahweh’s army puts in an appearance to Joshua personally to give him courage and direction for the taking of Jericho. Just as God appeared to Moses in the burning bush, so He now appears to Joshua.

The person appears in a military form. His sword is drawn in a stance of hostility. Joshua walks up to him and asks boldly whether he is for Israel or the Canaanites. The man answers with the word “no” a surprising answer. No wonder some Hebrew MSS have “to him” (the Hebrew word “no” and “to him” are pronounced the same way. This often leads to mistakes in copying). The reading would then be, “and he said to him, I have come as prince . . .” But it is more likely that the harder reading is the correct one (“no.”) The man asserts that he is no one’s employ except that of the Lord of Host. Joshua recognizes a very special being before him and falls on his face to do obeisance (this word does not require that the recipient be divine). He then asks, “What does my Lord require of me.”19

The first thing the man requires is that Joshua remove his sandals. This obviously relates this revelation to that of Moses in Exodus 3. It also indicates a divine presence. There is little question that this “man” is really a theophany, i.e., God has appeared to Joshua.

One might expect further instruction from the theophany, but none is given here. It is quite likely that the instruction found in 6:2-5 is given by the Prince of Yahweh’s host. Verse one would be inserted by the author to indicate the need for the instruction.

III. Conquering the Land (6:1—12:24)

A. Defeat of Jericho (6:1-27)

1. Before discussing the text, it is important to look at the general discussion of the ruins of Jericho and the implications of archaeology for the historicity of the fall of Jericho under Joshua.

This is a key city in which to look for archaeological help on the biblical data. Garstang (Digging up Jericho) in his excavations from 1930‑36 identified a set of burned walls as belonging to the late bronze age or the time of Joshua. K. Kenyon (“Jericho,” Archaeology and Old Testament Study) says that “This was . . . a completely erroneous identification, for the defenses in question belonged to the Early Bronze Age” (3000‑2300 by her reckoning). Archer, in a series on biblical archaeology in Bib Sac (1970), quotes Garstang (in 1948) as saying his position has not been refuted. Archer argues that this is a case in point where the prejudgment of one’s position (in this case a late date for the Exodus) controls the interpretation of the data. However, Miss Kenyon argues that “. . . it is impossible to associate the destruction of Jericho with such a date [late date]. The town may have been destroyed by one of the other Hebrew groups, the history of whose infiltrations is, as generally recognized, complex. Alternatively, the placing at Jericho of a dramatic siege and capture may be an aetiological explanation of a ruined city.20 Archaeology cannot provide the answer.”21 Bryant Wood takes an opposing view.22 In view of this conflict, it appears to me that it would be better not to call on archaeology for help in illuminating the siege of Jericho, but to accept the biblical account including the date of 1 Kings 6:1, which is not disproved by archaeology, and wait for further developments.23

2. The Strange Instructions (6:1-5).

This first battle initiating Israel to God’s deliverance and holiness must take place in a miraculous way. Only God’s priests carrying God’s ark of the covenant and blowing the shophar horns will bring victory. We learn further in 17-19 that the city and all its contents, people and things are under the “ban.” The word “ban” is from the Hebrew “Herem” which means devoted exclusively to God.24 This awful decree is indicated because Jericho was the first of the cities to be defeated by the Israelites. It was thus a sort of “first fruits” to the Lord. Like the new circumcision, new Passover, and new food, this first city must be dedicated completely to the Lord.

3. The mysterious, eerie march (6:6-11).

The army and the priests, carrying the ark, marched around the city six different days. What must the inhabitants of Jericho have thought as they peered over the wall and waited for the attack? They no doubt thought the walls of Jericho were impregnable, but they failed to reckon with the might of God.

4. The fall of the city (6:12-21).

On the seventh day, they marched around the city seven times. The number seven, of course, is a prominent number in the Old Testament. It shows perfection or completeness. On the seventh circuit, Joshua told the people to shout. This they did, and the walls fell flat totally exposing the city. The soldiers then poured into the city and wreaked havoc on the city, destroying all living beings.

The speech about placing the city under the ban sounds as though it is being made in the heat of the battle. Obviously, that is impossible, and we need to understand the Old Testament narrative style in which a speech made earlier to the people is inserted at the point where it has the most application.

5. The fulfillment of the vow to Rahab (6:22-25).

In spite of all that must have been on his mind, Joshua reminded the two spies to go to the harlot’s house and fulfill their vow to her. Thus, were Rahab and all her family saved from the destruction that enveloped the city. She became part of the family of faith, an ancestress of David and of Jesus the Messiah (Matt 1:5). All the precious metals were turned over to the priests to be deposited in the “house of the Lord” or tabernacle.

6. The terrible oath about Jericho (6:26-27).

Joshua declared that the man who rebuilt Jericho would be under a curse. His oldest and youngest sons would die in the process. This was fulfilled in 1 Kings 16:34.

B. Sin of Achan—Defeat at Ai (7:1-26)

1. The archaeological issues at Ai.

“And Joshua sent men from Jericho to Ai, which is beside Bethaven, on the east side of Beth‑el . . . they are but few.” (Josh 7:2‑3). Ha’ai means “the heap” (see BASOR, #198, April 1970).

According to Wright, Ai’s excavation indicates a small, flourishing town, heavily fortified, between the 33rd and 24th centuries B.C. The chief structure within was a fine temple, beautifully built and the huge walls were its protection.25

The city is said to have been destroyed about 2400 B.C. and not reoccupied until c. 1000 B.C. Attempts to answer this are:

a. Etiological explanation.

b. People from Bethel temporarily occupying the city.

c. Albright: Story in Joshua concerns Bethel but later it was identified with Ai.

Excavation shows a violent destruction of Bethel in the 13th century (Albright and Kelso—1934, 1955‑60). It is more probable that this is the destruction of Bethel referred to in Judges 1 at a later date.

Since the biblical account is quite explicit, we can only assume:

a. The occupation was so light as to leave no trace.

b. The mound excavated (et Tell) is not Ai.26

2. The first foray against Ai (7:1-5).

The chapter begins by informing us that the Israelites had acted unfaithfully against the Lord regarding the ban. The reason was that one of their people, Achan, had defiled the people by taking some of the stuff that had been dedicated to the Lord. The corporate aspect of God’s dealing with His people is on display here. “A little leaven leavens the whole lump” (1 Cor 5:6). This will cause the anger of the Lord to “burn against them” and they will lose the next battle. Again, the initiatory acts of the people must be accompanied by holiness. When God begins a new thing, he is very firm with His children.27

The spies concluded that Ai was lightly occupied and would be easily defeated. So, Joshua sent only 3,000, but they were defeated and lost 36 men. The result was psychologically devastating to the Israelites.

3. Joshua’s spiritual defeat (7:6-9).

Joshua assumes the mode of mourning. A catastrophe has taken place and God’s promises seem to mean nothing. Joshua is concerned that all the people of the lands will now defeat them and mock the name of the Lord.

4. God’s response to the sin problem (7:10-15).

Yahweh is not patient with Joshua. A disaster such as this should have alerted him to the probability of some act of disobedience on the part of Israel. So, God demands that Joshua rise up, stop feeling sorry for himself, and deal with the sin of Israel. Israel has lost the battle, says Yahweh, because of sin. They have violated the covenant. The demand is that Israel rise up and consecrate them-selves (as they had done prior to crossing the Jordan). He then tells Joshua the procedure by which the sin will be determined.

5. The sin revealed (7:16-21).

The procedure set out by Yahweh was followed, and Achan was finally exposed as the sinner. He explains what he did, a rather innocent thing he thought, but God views sin differently.

6. The sin punished (7:22-26).

The stolen material was found in Achan’s tent. They then took him, his family, and all his possessions to the valley of Achor and stoned them to death. This seems like harsh punishment, but sin unchecked will destroy God’s people. A memorial cairn was raised over Achan to remind the people of the danger of rebelling against God.

C. Defeat of Ai (8:1-35).

1. Divine instructions (8:1-2).

There is no mention of divine instruction at the first attack on Ai. It is not necessarily the case that Joshua cannot initiate action on his own, but in this case, at least, God’s intervention was necessary. In this instance God tells him to take all the people of war (not just a few as in chapter 7). The instructions include an ambuscade.

2. The plan of attack (8:3-9).

Joshua selected 30,000 to leave early and set up an ambush behind the city of Ai.28 Joshua and the main force will feint an attack on the city gates and then fall back as previously. As soon as this happens, and the men in the city are drawn out into the open, the ambuscade will attack and burn the city.

3. The attack (8:10-23).

The strategy set out by Yahweh is simple but ingenious. A group of soldiers will sneak in by night and set up an ambush from the rear. The main body will confront the city from the front and draw them away from the city by feigning defeat. Then the ambuscade will rise up, attack the city from the rear, and burn it. They will then come out and form a pincers movement with the main body, trapping the inhabitants of Ai between them (8:10-13).

The plan was put into motion and worked as Yahweh had said it would. Bethel is mentioned as being part of the Ai contingent in v. 17. Apparently, they had decided to join forces with those of Ai and thus became vulnerable to the same consequence (8:14-17).

When Joshua gave the signal (raised dagger) the flight stopped and the ambuscade came out and set the city on fire, leaving the people of Ai completely dispirited and afraid. Then the slaughter began, and the King of Ai was kept alive for future treatment (8:18-23).

4. The aftermath (8:24-29).

About 12,000 residents of Ai died that day. The ḥerem war of Jericho is followed here with one exception: the loot taken from the city may be kept by the soldiers. The city was burned and turned into a heap and the king was hanged.

D. The Altar in Mount Ebal and the law of God written and recited (8:30-35).29

The defeat of Ai (and Bethel?) opened up the way into the hill country and access to the area of Shechem (modern day Nablus).30 There surrounding the city are two mountains. Joshua built an altar on Mount Ebal and offered sacrifices on it.31 The law (ten commandments) was inscribed on the stones, and then the whole law was read (Deuteronomy?) with the blessings and the curses. All this was in fulfillment of Moses’ command in Deut 11:26-32.

E. Treaty with the Gibeonites (9:1-27)

1. The archaeological issues at Gibeon.

The Gibeonites made a league with Joshua (chapter 9) and became “hewers of wood” and “drawers of water.”

Gibeon was excavated by Pritchard from 1956‑1962 (It is not all finished). The most outstanding thing there is the huge water cistern 37 feet in diameter and 82 feet deep.32 In addition there was a winery with a capacity of 25,000 gallons.33 There is evidence of continuous habitation without destruction in accord with the biblical account.34

2. The coalition of Canaanite kings (9:1-2).

These petty kings were usually fighting against one another as the Amarna tablets indicate. Now with an overwhelming threat facing them, they decide to form an alliance for mutual protection.

3. The response of the Gibeonites (9:3-15).

The locus of the story in chapters 9 and 10 is Gilgal. Apparently, Joshua had returned there after the ritual activities at Shechem. The Gibeonites, on the other hand, recognized the futility of such action and so decided on a subterfuge as a means of survival (9:3-8).

They pretended to come from a distant country. The author again wants us to hear the rehearsal of God’s acts, so he records the testimony of the Gibeonites regarding God’s deliverance of Israel from Egypt and from Sihon and Og (9:9-13).

Joshua and the people, without consulting Yahweh, made a covenant treaty with the Gibeonites to allow them to live in their midst. This was a violation of what God had told them to do, but they were deceived by the ruse of the Gibeonites (9:14-15).

The ruse was revealed, and the Israelites learned that the Gibeonites were local and lived in four different cities. The army massed against the cities, but the elders warned against an attack because they had made a treaty with them. They furthermore offered a compromise: the Gibeonites would become slaves to the central sanctuary (9:16-21).35

Joshua confronted the Gibeonites and confirms the Elders’ decision to make them “hewers of wood and drawers of water.” The author again records their speech as a testimony to God’s activities among his people. He has promised them the land and the defeat of all its occupants. Therefore, the Gibeonites are content to be slaves rather than die (9:22-27).

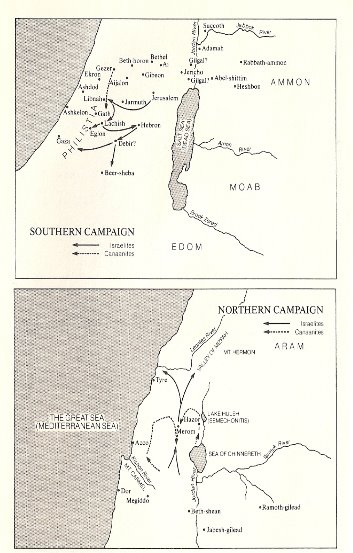

F. The Central Campaign (10:1-43)

1. The archaeological issues.

The defeat of these outpost cities was necessary to open up the hill country. When Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar invaded Judah centuries later, they followed the same strategy. All the cities mentioned in Joshua can today be located with a high degree of probability except Makkedah.36

Lachish.

Lachish was excavated by Starkey beginning in 1933. It was finished in 1957.

A jar was found with hieratic script of a receipt dated in the year of some Pharaoh. Which one? There is no real way of knowing, but Ramases II or Merenptah is usually chosen for obvious reasons (see chronology). It is the stele of Merenptah (c. 1220 B.C.) which contains the only mention of Israel and refers to them as a people in Palestine (ANEP p. 115, fig. 342).

Lachish letters are broken pieces of pot (ostraka) with writing on them. These come from Jeremiah’s time in the seventh century.37

Debir—Kiriath-sepher—Modern tell Beit Mirsim.

Albright’s own discussion of the archaeological data in Archaeology and Old Testament Study does not sound as conclusive as Wright indicates in Biblical Archaeology. One phase of the city was destroyed about the middle of the 14th century although an earlier or later date is possible.

The destruction of another level “must have been quite late in the 13th century B.C.”

I do not believe that Albright’s discussion is dogmatic enough to warrant a 1250 date for Israel to have defeated Debir.38

2. An alliance against Gibeon (10:1-5).

Adonizedek (the Lord is righteous), king of Jerusalem, appears to be the ringleader. Gibeon’s defection from a united front against Israel spelled danger to the other city states.39 So he sent to the kings of Hebron, Jarmuth, Lachish, and Eglon asking them to join him for a punitive raid against Gibeon.40 So they laid siege to the city.

3. The victory against the alliance (10:6-11).

Joshua received word from the Gibeonites who demanded that Israel fulfill her treaty obligations to them. After an encouraging word from the Lord, Joshua quick marched all night (as General Patton) to Gibeon and engaged the enemy.

The Scripture indicates that God directly intervened on behalf of Israel and against her enemies. It does not say how the Lord “confounded” the enemy, but it often refers to confusion in the ranks so that in a period of semi-darkness, the men turn on one another. Further, as the alliance fled, God rained hail stones on them large enough to kill them.

4. Joshua’s long day (10:12-15).

This account is probably one of the most famous in the Old Testament. There are two or three things we should note about it. 1) the statement is in poetic structure, and 2) the story was taken from the Book of Jashar, an otherwise unknown book which contained accounts of Israel’s victories.41 From an astronomy point of view, there is no way to explain this phenomenon. God was working miraculously to provide Israel with more daylight.42

5. The final end of the kings involved in the alliance (10:16-27).

The kings fled the battlefield and hid in a cave. Joshua told the people to wall them in and continue with the battle. After the utter defeat of the men in the alliance, Joshua had the men come forth, and had the Israelites put their feet on their necks as a symbol of God’s domination of the Canaanites through Israel. Then the five kings were hanged. As was Joshua’s custom, their bodies were removed at sunset in accordance with Deut 21:22-23.

6. The remaining central/southern campaign (10:28-39).

Joshua then followed up on his victory in the field by attacking and destroying cities: Makkedah, Libnah, Lachish, King of Gezer, Eglon, Hebron, and Debir (see the maps at the end of the Joshua notes).

7. Summary of the battles (10:40-43).

The summation of the battles is set forth in sweeping, hyperbolic terms. We know from other places that Joshua, while making a slicing attack against the Canaanites, did not defeat all of them, for many were left in the land. This is typical victory language used in the ancient middle east and must be understood as such.43

G. The Northern Campaign (11:1-23)

1. The archaeological issues.

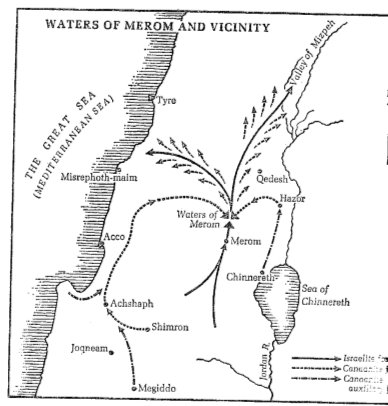

“And Joshua at that time turned back, and took Hazor, and smote the king thereof with the sword: for Hazor beforetime was the head of all those kingdoms.” Josh 11:10. See map on p. 46.

See Biblical Archaeologist XXII, 1959, and Yadin44 for a discussion. Hazor is mentioned in the execration texts and the Mari tablets. There was caravan travel between Hazor and Babylon. It was a huge city of 40,000 people.

Hazor was destroyed in the middle of the 13th century B.C. L. Wood says Hazor was burned but the evidence of destruction in the 13th century is not burning. But Stratum XVI (3) dated by Yadin in 16th‑15th centuries was burned. This may be the one Joshua burned, and it was rebuilt and strong during the time of Deborah.45

Conclusion about archaeological issues

We conclude our study of the conquest as we began. Archaeology is not as conclusive for a late date theory as is often presented, but neither does it give evidence for an earlier date. We will simply have to wait (perhaps in vain) for further interpretation and correlation which will help. The evidence does show violent disruption of many of the cities in the general period of the Exodus of Israel from Egypt. In the meantime, we should hold to the biblical chronology as given in 1 Kings 6:1.

2. Another coalition forms against Israel (11:1-5).

The movement is now to the north. Joshua has conquered the central and southern portions of the land. This time the big man is Jabin king of Hazor.46 He threw his net widely and encompassed three kings near him as well as several to the east and west. They joined forces at the waters of Merom in the Huleh valley north of the Sea of Galilee.47

3. Joshua has another great victory (11:6-15).

This unit begins with the customary hortatory word from Yahweh. Then Joshua’s sudden attack caught the enemy by surprise, and they were completely routed.48 Their war machine was destroyed as Joshua cut the tendons of the horses and burned the chariots. Chariots are an Egyptian innovation. In the hands of the Philistines, they will discomfit the Israelites in Saul’s day. Joshua then burned the city of Hazor (the only one in the northern campaign) and killed the residents. They treated them as ḥerem again except that, as with Ai, they were allowed to keep the booty. This unqualified language of destruction we have become accustomed to hearing and under-stand that it is the ancient near eastern way of describing victory without necessarily being taken literally in the details. Verse 15 again reminds us that Joshua was fulfilling the word of the Lord commanded to Moses.

4. Summary of Joshua’s conquests (11:16-23).

This is a theological statement. We know that a large number of tribal groups were never conquered. However, the blitzkrieg approach Joshua followed was successful. He was able to defeat all those who came against him from the north at the foot of Mt. Hermon to the Negeb in the south.49 The statement to Abraham in Gen 15:12-21 in which Abraham’s descendants are promised these very lands is now fulfilled. The judgment upon the Canaanites came through the Israelites. God gave them 400 years while the Israelites were in Egypt, but they did not repent, so God hardened their sinful hearts so that they would fight and die.

The reference to the Anakim (21-22) is appropriately placed here to counterbalance the account of the spies who were afraid to enter the land because of the Anakim (Num 13:33).

H. Summary of the War (12:1-24)

1. The victories on the east side of the Jordan under Moses (12:1-6).

2. This chapter is a summary of the conquest to this point. The territory on the east side of the Jordan had been allocated to Reuben, Gad, and half the tribe of Manasseh after the defeat of the Amorite kings under Moses.50

3. The victories on the west side of the Jordan under Joshua (12:7-24).

The extent of the land that was conquered by the Israelites is listed from north to south and east to west. Then a list of the ethnic groups is provided: Hittite, Amorite, Canaanite, Perizzite, Hivite, and Jebusite. It is clear from the book of Joshua itself that all this land was not controlled by Israel; they had merely established supremacy over it. There is much yet to be taken. The chapter concluded with the listing of 31 kings who were defeated.

IV. Dividing the Land (13:1—21:45)

A. The problem of unconquered land (13:1-7).

This section, above all, should make it clear that the language of conquest is ancient near eastern hyperbole. Joshua and Israel established supremacy in many ways, but the control of the land was yet to be accomplished. It is obvious from Yahweh’s description of Joshua’s age, that considerable time has passed. The best estimate for all the military activities is about seven years. The Lord tells Joshua that it is time for him to use his authority and position to carry out the complex task of allocating the land to the people of Israel.

B. Settlement on the east side of the Jordan (13:1-33).

1. Reuben’s inheritance on the east side (13:8-23).

2. Gad’s inheritance on the east side (13:24-28).

3. Half of the tribe of Manasseh on the east side (13:29-31).

4. Summary statement including the exclusion of Levi in the allotment (13:32-33).

Map from Boling, Joshua

C. Settlement on the west side of the Jordan (14:1—19:51).

1. Joseph’s inheritance (Ephraim and Manasseh) (14:1-5).

2. Judah’s inheritance (14:6—15:63).

The inheritance of Joseph is interrupted with the story of Caleb’s brave testimony and action against the Anakim. The second part of the story is found in 14:13-18, partially repeated in Judges 1:11-15. The prominent role of Judah in the future is represented in the details given to her allotment.

3. The house of Joseph’s inheritance, continued (16:1—17:18).

The reminder is there (as it was in 15:63) that only partial dominance had been achieved and much was left to be done (16:10).

The implementation of Moses’ instruction about female inheritance takes place (17:3-4).

Allotment of Manasseh’s land (17:5-13).

Joshua chides the house of Joseph when they complain that their allotment is too small. He tells them they are big enough to carve out their own territory and to take on the armies of chariots. This is further indication of the incomplete task of conquering the land (17:14-18).

4. Final allotment at Shiloh (18:1-10).

Shiloh is now the official site of the tabernacle. Here Joshua gathers the tribes together and chides them for not having completed their task of taking control of the land. He tells them to choose three men from each tribe and check out the land and take notes on it so that he can cast lots to proportion the land. Again, the Levites are mentioned as not being a part of the allotment. They will be cared for separately. The men checked out the land, brought back their survey, and Joshua cast lots for the remaining tribes.

5. The lot of Benjamin (18:11-28).

Benjamin will later be almost swallowed up in Judah. Particularly after the civil war in Judges 19-20, when they were decimated.

6. The lot of Simeon (19:1-9).

Simeon, even more than Benjamin, became swallowed up in Judah, because their inheritance was in the middle of Judah. Does this fulfill Jacob’s prophecy “I will disperse them [Simeon and Levi] in Israel and scatter them in Jacob”? (Gen 49:7).

7. The lot of Zebulun (19:10-16).

8. The lot of Issachar (19:17-23).

9. The lot of Asher (19:24-31).

10. The lot of Naphtali (19:32-39).

11. The lot of Dan (19:40-48).

The story of the Danite migration is told in more detail in Judges 17-18. This indicates that this portion of Joshua was not recorded until that time. This is the second account found in both Joshua and Judges.

12. The inheritance of Joshua in Ephraim (19:49-50).

13. The concluding and summarizing statement of the allotment at Shiloh (19:51).

D. The cities of refuge (20:1-9).

This interesting juridical practice was set in motion by Moses in Deut 4:41-43; 19:2ff. These asylum cities were to protect only those who had killed someone accidently. If the death was premeditated, the asylum was not to protect them. There were three cities on each side of the river and located to accommodate all the tribes.

E. The Levitical allotment of cities (20:10-42).

The Levites were allowed to have cities with surrounding pasturage. There were 48 cities in all.

F. Final theological statement about God’s provision of the land (21:43-45).

V. Settling the Land (22:1—24:33)

A. Joshua’s charge (22:1-6).

It has been a long and arduous struggle to conquer the land. Now the time has come to dismiss the two- and one-half tribes whose homes are on the east side. Joshua dismisses them with the charge “to observe the commandment and law which Moses gave them: to love the Lord your God and walk in all His ways and keep His commandments and hold fast to him and serve Him with all your heart and with all your soul.”

B. The return of the two- and one-half tribes to the east side (22:7-9).

C. The two- and one-half tribes build an altar (22:10-12).

From the beginning of her existence, Israel was threatened with dissolution. The centripetal force that drew them together was the central sanctuary. At this time, it was at Shiloh. This brought the tribes together with all their differences around Yahweh their God. (The “easterners’” fear was that they would be shut out of that relationship.) The centrifugal force that tended to drive them apart was tribalism. Each tribe tended to seek its own welfare and to go its own way. This force eventually triumphed with the separation of the nation into north and south. This altar was viewed by the main Israel camp as pagan and therefore a departure from the Lord. They met at Shiloh (note the emphasis on the new cult center where the tabernacle was located) and prepared for civil war.

D. The peace mission (22:13-20).

The people of Israel wisely sent a peace mission prior to attacking. They charge the “easterners” with committing an unfaithful act against the Lord. The word ma‘al (מַעַל) is the same word use in 7:1. The noun is only used with reference to an act of perfidy against God. The peace mission links this with the activity of Balaam against Israel that resulted in a plague (Num 25:1-9). Furthermore, they are concerned that the acts of the “easterners” will bring God’s judgment on all Israel as happened when Achan sinned. This leads them to refer to the sin of Achan which caused Israel to lose the battle at Ai. These are very serious charges.

E. The “easterners” defense (22:21-29).

The two- and one-half tribes say to the representatives who have chided them, “if we have done what you suggest, i.e., committed an unfaithful act against the Lord, or if we have built an altar for the holocaust offering or the grain offering, then may the Lord himself deal with us.” They almost swear an oath by saying, “The Mighty One, God, the Lord, the Mighty One, God the Lord” (22:21-23).

However, they say, we have not done that. This altar is not for burnt and grain offerings. It is merely a memorial so that the “westerners” will not forget that we belong to the Lord also. So, this altar is a “witness” between us.51 The memorial altar is a “copy” of the real one at Shiloh (22:24-29).

F. The happy conclusion (22:30-34).

The representatives are well pleased with this response by the “easterners.” Phinehas commends them for their answer and indicates full acceptance of the sentiment they have expressed through the altar. When they report back to the main body at Shiloh, they likewise are well pleased, and so the matter was resolved that could have led to a bloody civil war. The “easterners” call the altar “witness” because it was a witness between them and the “westerners” that Yahweh alone is God.

G. Joshua calls another solemn assembly (23:1-16).

The language of 23:1-2 is similar to 13:1. A significant amount of time has passed, and Joshua feels compelled to bring his people together to admonish them. The Lord has given rest to Israel, i.e., the military combat beginning with Jericho is over (23:1-3).

We are reminded again (v. 4) that there remains a lot to be done. Joshua says he has divided all the land by lots, but much of it is yet unclaimed. So, he encourages them to trust the Lord, be firm and keep the law of Moses. They are to avoid mixing with the nations who are left, because they will be tempted to join them in worship of false gods. If they fail to follow Joshua’s admonitions, the Lord will abandon them to their enemies, and they in turn will be “snares, traps, thorns, and whips” to Israel (23:4-13).

Finally, Joshua says he is near death, and as such, he must give them a dying man’s statement. Though they have seen all the good that Yahweh has done on their behalf, all that will be reversed if they disobey and follow false gods. The curses of the covenant (read from Mt. Ebal) will come upon them and destroy them. This prediction came about fully in succeeding ages (23:14-16).

H. Joshua’s farewell address (24:1-28).

Joshua assembled the people to Shechem (not Shiloh this time). He first of all recites the great acts of God: Call of Abraham, Jacob and Esau, Egyptian bondage and deliverance, wandering in the wilderness, victory on the east bank, defeat of Balak (and Balaam), defeat of Jericho, inheritance of a land that was not theirs. The hornet in 24:12 is thought by Garstang to be a representation of Egypt (as seen in the cartouches). Hence, he believes it refers to the debilitating influence of Egypt on the Canaanite cities52 (24:1-13).

This brings a concluding statement (in Hebrew, “and now”). In light of all God’s faithfulness to them, he admonishes them to serve Yahweh in sincerity and truth and put away the gods which your fathers served beyond the river and in Egypt and serve the Lord. Does this mean that some were still worshipping false gods? Today, he says they must make a choice. He and his house have made theirs: they will serve the Lord (24:14-15).

The people respond in the strongest language that they will not abandon the Lord (24:16-18).

Joshua reminds them that God is a demanding God. He will hold them accountable for their disobedience. The people respond strongly again, saying that they will serve the Lord. Joshua then sets up a stone as a witness that they have promised to serve the Lord. He also wrote the words in the book of the law of God. The words to which the people have just agreed, are treated as the Law of God, and so written in a book. The stone is erected to remind all passers-by of the covenant Joshua and the people entered into with God. Joshua then dismissed the assembly (24:19-28).

I. Coda on the death of Joshua, Joseph, and Eleazar (24:29-33).

Joshua was buried in his own territory in Ephraim. The people remained faithful to the Lord during Joshua’s lifetime and that of the elders who had witnessed God’s triumphs. The implication is that they will cease doing so upon the death of all these. That will be their condition when the Book of Judges begins. The bones of Joseph brought out at the time of the Exodus were buried. This is another sign of the fulfillment of all God’s promises, and of Joseph’s faith that the Land of Canaan was where his body belonged (Gen 50:24-26). Finally, Eleazar died and was buried.

Thus ends the great book of the conquest. It has been a mixed story. On the one hand, all God’s promises to Israel have been fulfilled in a general sense (triumph over all the enemies, land given to Israel), but on the other hand Israel was confined primarily to the hill country and significant numbers of Canaanites were left. Israel will do battle with them all the way through the time of Saul and David. It will be in David and Solomon’s time that complete control of the land will be in Israel’s hand. Maps from Woudstra, Joshua, Word Biblical Commentary

1Wright, “Introduction,” p. 40.

2So, the LORD said to Moses, “Take Joshua the son of Nun, a man in whom is the Spirit, and lay your hand on him; 19 and have him stand before Eleazar the priest and before all the congregation; and commission him in their sight. 20 “And you shall put some of your authority on him, in order that all the congregation of the sons of Israel may obey him. 21 “Moreover, he shall stand before Eleazar the priest, who shall inquire for him by the judgment of the Urim before the LORD. At his command they shall go out and at his command they shall come in, both he and the sons of Israel with him, even all the congregation.” 22 And Moses did just as the LORD commanded him; and he took Joshua and set him before Eleazar the priest, and before all the congregation. 23 Then he laid his hands on him and commissioned him, just as the LORD had spoken through Moses.”

3See Woudstra, The Book of Joshua, p. 22-26, for a discussion of the issues.

4See Bryant Wood, “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archae-ological Evidence,” BAR 16:2 (1990): 44-47, 49-54, 56-57.

5Frank J. Yurco, “3,200-Year-Old Picture of Israelites Found in Egypt,” BAR 16:5 (1990): 20-223, 24-28, 32-34, 36-37.

6See also “Rainey’s Challenge,” BAR 17:1 (1991): 56-60, 93, 96.

7Shanks, ed. The Rise of Ancient Israel. Biblical Archaeology Society, 2004.

8Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, p. 163.

9Ibid., pp. 173-174.

10Albright, From Stone Age to Christianity, pp. 280ff.

11Wright, “Introduction,” p. 30. His whole discussion on the “Divine Warrior” is an important read (pp. 27-37).

12These are clay tablets discovered at Tel el Amarna Egypt. They come from the 14th century B.C., are written in Cuneiform script, in the Akkadian language, and represent correspondence between the Pharaoh of Egypt and the various petty “kings” in Canaan. See William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters.

13Woudstra, loc. cit., p. 74 “Rahab thinks in terms of family and clan. This is in keeping with the thought patterns of the ancient Near East.”

14Garstang, Joshua, Judges, pp. 136-37.

15The hiphil of “qum” several times means simply to lift up (Deut 22:4; 1 Sam 2:8; 2 Sam 12:17).

16NIV captures my argument with, “Joshua set up the twelve stones that had been in the middle of the Jordan at the spot where the priests who carried the ark of the covenant had stood.” Adam Clarke (Commentary and Critical Notes, Vol. 12, Loc. cit. refers to Dr. Kennicut, who makes the same argument I do, but Clarke rejects it for lack of textual support.

17Woudstra, Joshua, p. 99, reminds us of the necessity of the circumcision of Moses’ sons before he could lead the people from bondage.

18See Ibid., p. 103 for a discussion of the apparent discrepancies between the Pass-over, Unleavened bread, and the eating of the produce of the land.

19Woudstra, Joshua, p. 105, says that the phrase “my lord” does not require that the person be deity because it is “adoni” and not “adonai.” However, in the first person, the singular/plural vowel with “adon” is the choice of the Masoretes, so, it could be Adonai.

20Wright, in “Is Glueck’s aim to Prove that the Bible is True?” Biblical Archae-ologist, XXII, December 1959, denies the etiological explanation.

21K. Kenyon, “Jericho,” p. 273.

22Bryant Wood (See “Did the Israelites Conquer Jericho? A New Look at the Archaeological Evidence,” BAR 16:02) has taken up the issue again and argued that Kenyon misinterpreted some of the data.

23See further, Wright, Biblical Archaeology, pp. 79, 80, Wood in New Perspectives on Old Testament Studies, and Waltke, Bib Sac, J‑M, 1972).

24The Arabic word “harem” is related, meaning a group of women dedicated exclu-sively to the Sultan.

25Wright, Biblical Archaeology, p. 80.

26See Livingston, Westminster Theological Journal, 33, Nov. 1970, p. 20f. He argues that Bethel is really modern Bira and Ai an unnamed mound nearby.

27Note the death of Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5 as the church was beginning.

28Excursus on the problem of the numbers 30,000 in v. 3 for the ambuscade and 5,000 in v. 12. Conservatives tend to argue for two ambuscades, but their location to the west of the city seems to argue against this. Critical commentaries see two different accounts that have been redacted into one but containing contradictions. Greek (B) has smoothed it out by omitting the second number and saying simply, αἱ πᾶς ὁ λαὸς ὁ πολεμιστὴς μετʼ αὐτοῦ ἀνέβησαν καὶ πορευόμενοι ἦλθον ἐξ ἐναντίας τῆς πόλεως ἀπʼ ἀνατολῶν καὶ τὰ ἔνεδρα τῆς πόλεως ἀπὸ θαλάσσης “All the people of war with him went up and came before the city from the east. And the ambuscade of the city was from the west.” Keil and Delitzsch (Joshua and Judges, p. 86) argue that an error in the transmission of the first number must have occurred. Thus the 30,000 should be 5,000 and the second account is simply restating the first one. Something like that must have happened. It would be tempting to follow the LXX here, but they are probably smoothing out the problem their own way. Boling (Joshua, p. 239) refers to the 5,000 as five contingents, “another way of referring to the 30,000.”

29See Machlin, Joshua’s Altar, for a popular presentation of Adam Zertal’s altar.

30The easy access to central Canaanite territory raises the question of why. Boling (Joshua, p. 63) says, “The etiological saga about the occupation of Ai (chap. 8) and of Gibeon and related cities (chap. 9) indicate that the Samarian middle of the country was also captured by the Israelite tribes.”

31See Adam Zertal, “Has Joshua’s Altar Been Found on Mt. Ebal?” BAR, 11.1 (1985): 26–35, 38–41, 43.

32Pritchard, ANEP, #810, 876, 878, 879.

33Pritchard, Gibeon, Where the Sun Stood Still.

34See Reed, “Gibeon” in Archaeology and Old Testament Study, pp. 231-243.

35Note the religious activity at Gibeon in the pre-Davidic period: 2 Sam 2:12ff?; 1 Kings 3:4;1 Chron 16:39; 21:29; 2 Chron 1:3, 13.

36Wright, Biblical Archaeology, p. 81.

37Pritchard, ANEP, #808.

38See J. Hoffman, “What is the Biblical Date for the Exodus? A Response to Bryant Wood,” JETS 50/2 (June 2007) 225–47.

39Note the repeated statements of the fear generated in the Canaanites by the awe-some acts of God on behalf of His people (2:10-11; 5:1; 9:1-2, 24).

40Garstang, Joshua, Judges, p. 177, says, “We have already realized that the com-position of the league assembled by Adonizedek could hardly be explained merely as the banding together of neighbouring cities for their mutual protection; and it now becomes fairly obvious that this combine represents a political organization, the rally under a responsible head of cities still faithful to the Pharaoh, in a punitive expedition against the chieftains who had entered into alliance with the Hebrews, one of the disturbing elements of the day.”

41This book is also referred to in 2 Sam 1:18 as the source of David’s lament over Jonathan. Woudstra, Joshua, p. 176, says, “The work appears to have been a collection of odes in praise of certain heroes of the theocracy, interwoven with historical notices of their achievements.”

42An “urban legend” has been circulating for several years that the NASA scientists found a gap of one day in history and determined it to be Joshua’s long day. There is nothing to the account (I have checked with NASA people) and yet it keeps circulating.

43See the discussion of Kitchen on page 13.

44Yadin, Archaeology and Old Testament Study, pp. 245-263.

45See Wood, New Perspectives on the Old Testament, p. 66ff.

46There is a man with the same name in Deborah and Barak’s battle with Hazor in Judges 4-5. This is no doubt a dynastic title borne by successive kings. Boling, Joshua, p. 304, says, “This is the shortened form of a sentence name, ‘the god N has created/built.’ It is a Hazor dynastic name, as known from an unpublished Mari text, which also yields the name of the patron deity, when it mentions ‘Ibni-Adad, king of Hazor.’”

47For an excellent discussion of the geographical references, see Boling, Joshua, pp. 304-06.

48Boling, Ibid., p. 311, suggests that the hamstringing of the horses took place prior to the raid, and thus the soldiers had no horses for their chariots.

49Woudstra, Joshua, p. 194, says, “The author now comes to a provisional con-clusion to his narrative of the Conquest. Though at late points (e.g., 13:1; 15:63; 16:10) he will point to the incompleteness of the Conquest, at this stage he emphasizes that, from a certain viewpoint, one could say that the whole land was taken.”

50Again, for a good summary of the geographical data, see Boling, Joshua., pp. 323-29.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Teaching the Bible