3. Ruth

Related MediaA. The third appendix, a godly line established (Ruth 1:1—4:22).

After working through the book of Judges, one feels the need of a shower. This makes the little book of Ruth a shower most refreshing. It is an idyllic, godly respite in the midst of the canaanization of the Jewish people. The sordid story of the acquisition of wives for the Benjamites is in sharp contrast to the acquisition of a wife by Boaz. The mutual concern of Naomi and Ruth is radically different from the attitude of the Levite to his concubine wife.

1. Struggling in Bethlehem (1:1).

The existence of a famine is an oxymoron in an area known for its productivity. Bethlehem means “house of bread.” The story happened sometime during the period of the judges, but obviously, it is being produced in final form after the time of David. It, no doubt, is designed to help elevate the family of David, perhaps over the family of Saul. The famine caused a migration to a part of the world that was not under a famine.

In contrast to the book of Judges, everyone has a name: Elimelech (my God is King); Naomi (pleasant); Mahlon (sickly); and Chilion (puny). This whole family unit made the fairly long journey to Moab1 and settled there.2

2. Struggling in Moab (1:2-5).

Unfortunately, this major family move did not prove salutary. First, Elimelech died. Then her two sons married Moabite girls. Orpah, the meaning of whose name is uncertain, but some suggest that it is a variant of Oprah, a gazelle, and Ruth. BDB derives her name from רְעוּת Re‘uth meaning “friendship.” HALOT derives it from a different root, and so (refreshment.)3 Then the two boys died. We are told that the family lived there for ten years, but the intermediate time elements are not given, however, since there were no babies, the boys must have died shortly after marriage.4 So, Naomi was left with no blood kinsman.

3. Returning to Bethlehem (1:6-18).

Rumor has announced that Yahweh had returned prosperity to the house of bread.5 Consequently, Naomi packs up her meager belongings to go home. Her daughters-in-law are with her. 6 They started out on the arduous trek to Judah. Naomi turns to her two daughters-in-law and urges them to return to their parents’ home. The MT (ketib) says that Yahweh will show kindness to them as they have toward her but reads (qere) a form that makes it a prayer, “May Yahweh show you kindness…” Her prayer continues, asking Yahweh to make them find rest, each in the house of her husband. The women were still young, so, she prays that they will find a second husband. Then she kissed them, and they cried. In unison, they said, “let us return with you.” (1:6-11).

Naomi explains, logically, that she is incapable of providing more sons as husbands. Even if she could, they would not be willing to wait until they were grown. She does not want them to share in the bitterness she has received from the hand of Yahweh on their account. Here is the first mention of her bitterness (cf. 1:20). The meaning is not clear as to whom she compares her bitterness. Campbell says, “She makes her case against God stronger by comparing her condition to that of her daughters-in-law.”7 So, they both weep again, and Orpah leaves to return home, 8 but Ruth clings to Naomi (1:12-14).

We now turn to one of the most beautiful accounts in the Bible. Naomi urges Ruth to follow Orpah. Ruth begs Naomi to stop urging her to leave her. “Wherever you go, I go, and wherever you stay, I will stay; your people will be my people, and your God, my God. Wherever you die, I will die and be buried. Thus, may Yahweh do to me [the oath formula] and even more, if anything but death separate us.” Ruth is acknowledging her allegiance to Yahweh, not Chemosh the god of the Moabites. So, Naomi accepted the determination of Ruth to go with her and gave up urging her (1:15-18).

4. Coming home after a ten-year absence (1:19-22).

As they entered the village of Bethlehem, the women gathered around in astonishment. They had assumed they would never see her again. They ask, “Is this really Naomi.” However, Naomi replies bitterly, “Do not call me pleasant, but call me bitter, for Shadday (the Almighty) has treated me very bitterly.” Here she uses Shadday not Yahweh because she argues that God could have prevented her problems had he chosen to. She says that she went out full, but Yahweh has returned her empty. So, why should you call me pleasant. Yahweh has answered9 (in court) against me, and Shadday has mistreated me. Now she brings both names into the action. Whether the covenant keeping Yahweh or the powerful Shadday, she has been the brunt of bad treatment.

The narrator concludes with the statement that Naomi and the foreign girl Ruth returned to Bethlehem at the beginning of the barley har-vest.10

5. The kinsman redeemer (goel) (2:1-3).11

The kinsman redeemer or goel has four usages in the Old Testament. The classic passage is Lev 25:23-28. 1) when a person sells land because of poverty, the next of kin is to buy it back so that it can stay in the family. If he has no kinsman, but he regained his prosperity, he may buy it back himself. He buys it back on a pro-rata basis. If he is unable to buy it back, it remains in the hand of the purchaser until the year of Jubilee (Lev 25:10). An example is found in Jeremiah 32, where Jeremiah’s cousin, Hanamel, asked Jeremiah to buy property occupied by the Babylonian army. 2) Blood avenger (Numbers 35). The next of kin is to kill the one who killed a man. The cities of refuge were established to allow room for accidental killing. 3) An Israelite sells himself to a sojourner as a slave (Lev 25:47-5). A kinsman may redeem him on a prorated basis. 4) God as the goel of Israel appears 21 times in Isaiah alone. So, in the Book of Ruth, the redemption of Abimelech’s land by Boaz is clearly the enactment of the redeemer of land to keep it in the family.

A second set of laws is merged into the Ruth story: the levirate12 marriage. This practice is defined in Deut 25:5-10. If a man dies without a son, his brother is obligated to marry the widow. The first son born to this union belongs to the dead brother and inherits his property. The implementation of this practice is found in Genesis 38.

The story of Ruth and Boaz does not quite fit the regulation.13 Boaz is not Elimelech’s brother; even if so, he should not marry Ruth, but Naomi. Thus, we have a mixture of the practice of goel of property and partial levirate marriage. The implementation of this was probably lax and, therefore, allowed for flexibility.14

So, we meet Boaz. Note that he is a relative of Elimelech, not Mahlon, but it is through Ruth that he raises seed to Elimelech.

This Boaz is a אִישׁ גִּבּוֹר חַיִל ish gibbor ḥayil. This phrase appears some 15 times (plus אשׁת חיל ishet ḥayil of Ruth in 3:11, and of the virtuous woman in Proverbs 31). In the plural (men of valor), it appears some 29 times. The vast majority of the times it refers to fighting men (especially in the plural). Here in Ruth, the translators struggle to know how to deal with it. KJV “mighty man of wealth”; NASB “great wealth”; ESV “a worthy man”; NIV “a man of standing.” I once read an article (now lost to me) where the author posited that Boaz was a member of the militia. This is more in keeping with the basic meaning. However, we also have Proverbs 31:10 where a good woman is referred to as a woman of valor. She is not a gibbor (man). In any event, Boaz is one who stands out.15 It is important to note that he is a kinsman of Elimelech.16

Ruth displays her diligence (see Proverbs 31) in setting out to provide food for her little family as only poor people can. Joüon cites Janssen regarding a scene where poor Arabs glean in modern times.17 It was “just her luck” to ask at a field owned by Boaz.18 The narrator, of course, is committed to the idea that Yahweh is engineering this whole process.

6. The kinsman redeemer notices (2:4-7).

And look! Says the narrator. Here comes the man himself. He called out a greeting (really a blessing) to the reapers. They respond in kind. All this sets the frame for the picture that Boaz is a good, godly man. He looks behind the reapers and sees a young woman. He turns to the man in charge and asks, “To whom does this girl belong?”19 His response is brief but clear, she is the Moabite girl who came back with Naomi from Moab. She asked permission to glean, and she has been at it all day except for a bit of rest in the house.20

7. The kinsman redeemer gives special attention (2:8-16).

Boaz begins the choreography by urging her to spend the rest of the harvest in his field.21 He tells her he has charged the young men to leave her alone (was this a common problem?). Furthermore, when she is thirsty, she is to come to the water station and drink. She fell on her face and expressed her thanksgiving, but Boaz said that he already knows her story. He calls on Yahweh to fully reward her; this Yahweh under whose wings she has taken refuge.22 She again expressed her appreciation (2:8-13).

He takes it one step further. He tells her to come to the place they eat and participate with them. The Hebrew is subtle, but it looks as though he, himself, dipped some parched corn for her in the vinegar, she ate it, was satisfied, and had some left over. After lunch, she went back to work, and he charges the servants to let her glean among the sheaves and not to insult her. Furthermore, he tells them to pull out some of the stalks and leave them for her and again tells them not to rebuke her (2:14-16).

8. The kinsman redeemer revealed (2:17-23).

Ruth kept working until the evening, then she beat out the grain and had about half an ephah of barley. This comes to approximately one-half bushel. She shows23 this, plus the extra parched grain, to Naomi who is amazed. She wants to know where she gleaned to get so much barley. She told Naomi everything, including the name Boaz. Naomi praised God and told her he was a near kinsman, one who could redeem them. Naomi agreed with Boaz that she should stick with his maidens so that no one could molest her in another field. Consequently, she stuck with Boaz’s maidens until the barley harvest and wheat harvest were over. During that time, she stayed with her mother-in-law.

9. Naomi’s plan of attack (3:1-5).24

Naomi, having come to know who Boaz was, as a potential husband for Ruth, sets out to create a situation in which he commits himself.25 She says to Ruth, should I not seek a pleasant rest26 for you? 27 “Rest” in this context means security and care from a husband (3:1).28

Now, she says, “Boaz, our acquaintance, with whose female servants you were—look, he is winnowing on the barley threshing floor tonight.” Winnowing consists of throwing the stalks into the air after beating them with a flail. The wind blows away the chaff (Psalm 1:4), and the grain falls to the ground.29 She then tells Ruth what to do.30 These are short commands: wash, anoint, put on your garment, and go down to the threshing floor.31 She is not to reveal herself until he has finished eating and drinking. Next, when he lies down, she is to mark the place, uncover his feet, and lie down. She tells her that Boaz will take it from there. Ruth agreed to do all this (3:2-5).

10. The encounter on the threshing floor (3:6-13).

She did as she was told, and when Boaz had eaten and drunk, he was tipsy (his heart was good), and he lay down by the heaps (of barley). She came quietly and uncovered his feet (literally, the place of his feet). This action would presumably awaken him when his feet became cold.32 In the middle of the night, Boaz awoke trembling and looked all around. Look, there was a woman lying at the place of his feet. He asked her who she was, and she replied, I am Ruth your servant, therefore,33 spread out your garment (wing) over your handmade, for you are a kinsman redeemer (3:6-9).

What is this strange request Ruth, makes? Ezek 16:8 spells it out explicitly as an action of Yahweh with Israel: “I crossed over to you and saw you, and look, your time for loving had come. So, I spread my garment (wing) over you, and covered your nakedness. I swore to you and entered a covenant with you, says Yahweh, and you became mine.” This makes it clear that Ruth was asking Boaz to marry her.

Boaz praised her for her kindness to him (latter kindness, ḥesed) in that she has chosen an older man rather than one of the young guys. So, he understood her actions to be a request of marriage, and he commits himself to it (3:10).

However, there is an impediment, she has a nearer kinsman than he. He tells her to spend the night, and, in the morning, the great shootout will begin (3:11-13).

11. The kinsman redeemer ensnared (3:14-18).

Ruth lay at his feet until the crack of dawn (did either of them sleep?), and Boaz said, “We do not want anyone to know that a woman has come to the threshing floor.” Boaz is concerned about the reputation of both of them. He told her to make a lap out of her robe.34 He measured six measures of barley.35 He put the barley on her, and she went36 to the village (4:14-15).

She came to her mother-in-law, who said (probably loudly), “who are you, my daughter?” This construction means “what is your situation?” Naomi had probably been up all night. Now she’s anxious to hear how it all came down. So, Ruth told her everything, as well as showed her the six measures of barley. Naomi told her to sit tight and wait to see how it would all fall out. She was sure that the man would not stay quiet until he had solved everything.

12. The kinsman redeemer checkmates the closer kinsman (4:1-6).

As Naomi suspected, Boaz wasted no time dealing with the issue.37 He was well prepared and rehearsed as to what to say and do. The gates of walled cities had seats installed where official business could take place. He went to the gate early and took a seat.38 He must have known the habits of the near kinsman. When he strolled by, Boaz invited him to take a seat. He does not name him, because the storyteller wants him out of the picture. Consequently, he calls him “Mr. so-and-so.”39 Then Boaz took ten men of the elders of the city and seated them in the gate (4:1-2).

Boaz then addressed the near kinsman. That piece of land belonging to our relative (literally, brother), Elimelech, Naomi, who returned from Moab is selling.40 “So, I said, I will tell you about it (literally uncover your ear), saying, acquire it before those sitting here and before the elders of my people. If you want to redeem it, redeem, but if you will not redeem it, tell me so that I might know, for you are the only one to redeem it, and I am after you.” The near kinsman almost nonchalantly says, “I will buy it.” The “I” is emphatic (4:3-4).

Then Boaz pulls the string on the trap. As soon as you get the field from Naomi,41 you also get Ruth, the Moabitess, the wife of the dead, so as to raise up the name of the dead on his inheritance.42 The near kinsman immediately demurred because of his fear of what it might do to his inheritance.43 “You go ahead and redeem my redemption rights” (4:5-6).

13. The kinsman redeemer’s triumph (4:7-12).

The narrator, who is some distance in time from the events, explains what is about to happen. Any kind of redemption or exchange was accompanied by the removal of a sandal and giving it to the other party. This became a testimony in Israel. The near kinsman did just that. This practice is different from the original goel legislation in Deut 25:5-10. There, the woman pulls off the man’s sandal and spits in his face. Time apparently has affected the tradition.

Now, Boaz was free to turn to the people gathered, and to the ten elders, “You are witnesses that I have acquired all that was Elimelech’s and all that was Chilion’s and Mahlon’s from Naomi. And also, Ruth the Moabitess, wife of Mahlon, I have acquired as a wife to establish the name of the dead on his inheritance, so that the name of the dead would not be cut off from his brothers and the gate of his place—you are witnesses this day.” Everyone happily agreed, raised their hands as witnesses, and prayed a prayer: “May Yahweh make this woman who has come into your house like Rachel and Leah, the two of whom built the house of Israel. And may he acquire wealth in Ephrathah, and may people call out his name in Bethlehem. Furthermore, may your house be like the house of Perez44 whom Tamar birthed to Judah. All this from the seed which Yahweh will give you from this woman.”

14. The marriage made in heaven (4:13-17).

Marriages were made when a man took the woman to the bridal chamber and consummated the relationship. Soon Ruth was pregnant and produced a son. Naomi plays a different role. Under ordinary circumstances, Boaz would marry Naomi and raise up seed to Elimelech. Since Naomi was beyond childbearing age, it is Ruth who has the child, but he belongs to Naomi. So, the women said to Naomi, “You are blessed of Yahweh who did not allow a redeemer this day to cease, and his name will be called out in Israel. This child shall restore your life and sustain you when you get old, because your daughter-in-law who loves you, has given birth to him. She is better to you than ten sons.” Naomi then took the baby, placed him in her bosom and became his nurse. The neighbors called out a name for the baby saying, “A son has been born to Naomi.” So, they called him Obed (he is the father of Jesse, the father of David).

15. The main purpose of the book of Ruth (4:18-22).

Suddenly, there is an insert into the story that takes us back to Genesis, “these are the generations of . . .” A genealogical list of ten names, culminating with David is given. Ten is an important number in genealogies. One has to ask whether the ten names provided are in any sense related to the prohibition of the Moabites from entering the assembly of the Lord (Deut 23:3). I suspect Jack Deere has it right, “The treatment of Ruth, however, by Boaz along with other Israelites of Bethlehem demonstrates that this law was never meant to exclude one who said, ‘your people will be my people and your God, my God’ (Ruth 1:16).” 45 It is astounding that this foreign woman, and a Moabitess at that, is now placed on a par with the matriarchs of Israel and included by Matthew in the genealogy of Jesus.

1The theological implications of Elimelech’s action are discussed by Block, Judges, Ruth, pp. 626-27.

2Language would not have been a problem (see the Moabite stone). There would have been dialectical differences.

3Koehler-Baumgarten, Hebrew and Aramaic Dictionary of the Old Testament, op. cit.

4Joüon, Ruth, says, “The text does not say that Orpah and Ruth lived ten years in marriage, but that the two sons (and Naomi) resided ten years in Moab,” p. 33.

5Block, Judges, Ruth, p. 631, “The ‘house of bread’ is being restocked.”

6Joüon, Ruth, says, “To be loved so deeply by her daughters-in-law, Naomi would probably be the most loving of mothers-in-law. The unselfish nature of her affection is shown in her efforts to dissuade her daughters-in-law from sharing her sad life and her concern to find a husband for Ruth,” p. 9.

7Campbell, Ruth, p. 70.

8Block, Judges, Ruth, p. 606 argues that Naomi may not be a “confessional mono-theist.” Still when she urges the girls to go back, she appeals to Yahweh to bring his blessing upon them.

9Greek has “afflicted me.” The consonants are the same for both meanings. Joüon suggests a different reading, “He has acted against me,” p. 43.

10Generally, in April.

11See Boling, Ruth, p. 109, for a discussion of the literary structure of this chapter.

12Levir, means “brother-in-law” in Latin.

13Boling, Ruth, p. 109, uses “covenant brother” to indicate relationship entered into voluntarily rather than the accident of blood relationship.

14See Joüon, Ruth, p. 16, “In the book of Ruth, we are not really dealing with a levirate marriage, but only a marriage of the levirate type.” See his discussion for more details, pp. 14-17.

15Block, Judges, Ruth, p. 651, says, “Boaz is not an ordinary, run-of-the-mill Israelite. This will be confirmed by the following episode, where he is presented as a man with land and servants. On the other hand, as in Prov 31:10, which employs the feminine equivalent, the name can also mean ‘noble with respect to character’ a genuine Mensch.”

16Joüon, Ruth, p. 45, “literally mighty of power, has here (and in 1 Sam. 9:1) the sense of very rich. חיל ḥayil has also the sense of riches in 4:11 (but 3:11: virtue).”

17Ibid., p. 48.

18This stress on “luck” is designed to draw attention to God’s sovereignty at work. It is similar to Esther 4:14: “another place” and “you have attained royalty for such a time as this.”

19The lamed in לְמִי lemi indicates that she belongs to someone. Joüon, Ruth, p. 47.

20This is a difficult phrase. See Joüon, Ruth, p. 49, who translates, “she has not taken even a little rest.”

21Some are cynical about Ruth’s motives, but Boling, Ruth, says, “His characters are to be taken at face value and without devious motives. This is important to realize here in chapter 2, and all the more important for understanding chapter 3 correctly. What is at issue here is men and women, old and young, living out publicly the sort of lives the storyteller commends,” p. 112.

22Block, Judges, Ruth, p. 219, says, “In the man who speaks to this Moabite field worker biblical ḥesed becomes flesh and dwells among mankind.”

23The Hebrew has either, “she showed her mother-in-law (as here) or “her mother-in-law saw.” I have followed the former with a few MSS, Syriac, and Vulgate.

24Boling, Ruth, pp. 130-33 has an excellent discussion of the literary skill of the narrator.

25Ibid., p. 124, “Ruth’s action has put Boaz on the spot, and that is what it was intended to do. Boaz must now act, and, of course he will do so in accordance with what righteous human behavior calls for.”

26In 1:9 she prays that Yahweh will make it possible for the girls to find מְנוּחָה menuḥah (“rest”) each in the house of her husband. Now Naomi sets out to assist Yahweh in the fulfillment by seeking מָנוֹחַ manoaḥ “rest.” Joüon, Ruth, says this is a different form but with the same sense, p. 63.

27Hebrew: “which will be good for you.”

28“The verbal link [with 1:9] invites the reader to consider whether subsequent events are to be viewed not only as the consequence of Naomi’s scheming, but also the result of her prayer in 1:8-9,” Block, Judges, Ruth, p. 681.

29See Joüon, Ruth, pp. 64-65 for a fuller discussion of winnowing.

30Hebrew uses the waw consecutive perfect as an imperative.

31Block argues that these actions indicate an end of her mourning for husband. This is attractive, but there is no way to know how long her mourning period was, Judges, Ruth, p. 684.

32Joüon, Ruth, p. 68.

33Waw consecutive perfect again as an imperative or a request.

34The only occurrence of this word. It is probably the same as the garment in 3:3, Boling, Ruth, p. 127.

35We are not sure of the amount, but it was a lot! He did not want to send her to her mother-in-law empty, the same word Naomi used of herself in 1:21, Boling, Ruth, p. 128.

36Hebrew: “He went,” but a lot of MSS have “She went.”

37Block, Judges, Ruth, says that the lack of the usual waw consecutive imperfect to show sequence, “by front-loading Boaz, the reader’s attention is drawn to this character. Admittedly Ruth’s fate will be a key issue in the court proceedings, but the narrator hereby forces the reader to focus on Boaz,” p. 704.

38See Block, Judges, Ruth, for a discussion of God’s hidden hand in the events, p. 705

39Of course, these are the narrator’s words. Boaz would have used his name, Joüon, Ruth p. 76, but see Boling’s long discussion, Ruth, pp. 142-43.

40Ibid., for a discussion of the time of selling, but see Block, Judges, Ruth, p. 710, for an entirely different discussion of the meaning of this word.

41The KJV translates “Thou must buy it also of Ruth . . .” They are following the MT, but most now treat the מ “m” from as an enclitic “m,” used for emphasis.

42Block, Judges, Ruth, p. 715, says, “Because the personal story of these characters must lead inexorably and ultimately to David, this sentence is one of the most significant in the book.”

43See Joüon, Ruth, pp. 80-81, for a discussion of the nearer kinsman’s situation relative to the property.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Teaching the Bible

4. 1 Samuel

Related MediaI. Historical background to the Books of Samuel.2

The beginning date for the activity of the Books of Samuel is early in the eleventh century B.C. The Hittites, Mitanni and Babylon were kingdoms in decline or complete defeat during this time in the north. The Arameans or Syrians began to move into the northern area in large numbers but did not consolidate until after David’s time.

The Sea People (from the Aegean) had invaded the entire Levant in the preceding century. They were defeated by the Egyptians, but at great cost to the latter who were weak during the time of the judges. Some of the Sea People became the Philistines. They apparently brought with them the secret of iron smelting which they kept for themselves and dominated the Israelites.3

The Canaanites were subdued by the Israelites and the Philistines. Pockets of them were probably under Philistine control as they had previously been under Egyptian control. Some Canaanites moved to Tyre and Sidon and became great maritime people, establishing colonies along North Africa and in southern Spain. They were called Phoenicians.

There were small kingdoms on the eastern border called Ammon, Moab, and Edom. There were continual clashes between them and Israel. Israel, during the time of the Judges, was struggling to consolidate her power particularly in the central hill country. Her religious state as a whole was abysmal. She had adopted many of the practices of the Canaanites. There was a centrifugal force (tribal units) and a centripetal force (central worship). These forces obviously created constant tension. Israel moved rapidly under David and Solomon to become the most powerful nation in the Middle Eastern arena.4

II. The place of 1 and 2 Samuel in Israel’s history.

Judges is a period without a king, with much internecine conflict and considerable practice of paganism and accompanying immorality. Ruth is a delightful interlude to an otherwise tragic drama. There is a central sanctuary, but the pericope on the Danite migration (Judges 17‑18) may indicate little support for the priesthood and a typically independent approach to religion and rule.

1 and 2 Samuel form a transition between the judges who were raised up spontaneously by God to be charismatic defenders of his people and the monarchy, an inherited rule of one who was to represent, defend, and judge God’s people.

The man Samuel looms large in this transition. From his Nazirite youth to his recall after death, he was a man of deep convictions, impeccable conduct, and unrelenting commitment to the cause of right. Yet, his compassion for Saul is evident when Yahweh rebukes Samuel for continuing to mourn Saul after his rejection.

III. The authorship and composition of the Books of Samuel.

The name Samuel is attributed to the books because he dominates the history of the era. That he did not write them all is obvious from the fact that he was dead during the entire period of 2 Samuel. The books were originally one, which accounts for Samuel’s name being attached to both books. The LXX used 1‑4 Kingdoms to describe 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings.

Samuel and other prophets were involved in writing as indicated by 1 Chron 29:29f: “Now the acts of King David, from first to last, are written in the chronicles of Samuel the seer, in the chronicles of Nathan the prophet, and in the chronicles of Gad the seer.”5 Did the account of Nathan’s confrontation with David and the Davidic covenant come from that prophet’s hand? Samuel’s records of the kingship (1 Sam 10:25) probably are reflected in that section of the book. The final form of the book may have come about through court prophets, but we do not know who finally composed the book from the various sources.

IV. The text of Samuel.

The text of Samuel contains a number of corruptions. Haplography is one of the more common problems. Some help comes from LXX and Qumran, but all this material must be evaluated carefully before trying to correct the MT. It is unfortunate that Cross has not yet published the Samuel texts from Qumran after more than four decades. Some of the work appears in the critical apparatus of BHS.6

V. The purpose of Samuel.

These books were not written merely to present history. Their contents are historical, but the arrangement and emphases are to point up God’s work among His people through the judges (e.g., Samuel) and through the kings. Much of the book is to show God’s plan in rejecting Saul and selecting David with whom he makes his covenant and promises a dynasty (2 Samuel 7). The place of the sanctuary is also central to the book when one compares the loss and restoration of the ark (1 Samuel 4‑6) with David’s placement of it in Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6) and the plan for the temple with the ensuing covenant (2 Samuel 7) and finally with the discovery of the place of the future temple (2 Samuel 24).

VI. Synthesis of Samuel.

The books of Samuel were composed after the death of David from court records, eyewitness accounts, and the writings of the prophets Samuel, Nathan and Gad. Though there are many sub themes running through the books (such as obedience and reward), the main purpose of the books seems to center on the concept that God is working out his divine purposes through the covenant kindness shown to David and his seed.

Few would question this thesis in 1 Samuel 16—2 Samuel, but even in 1 Samuel where Samuel is being contrasted to Eli’s house, this seems to be the case. Samuel will bring the word of judgment on Eli’s house, and David (via Solomon) will execute it over fifty years later (1 Kings 2:26-27). In the concluding verse of Hannah’s psalm (2:10), the king/anointed is mentioned. For Hannah this was a non-specific statement predicated on earlier statements about the coming monarchy (Gen 17:6); from the author’s viewpoint, this could only refer to David.

The “man of God” who brings a prophetic word against the house of Eli says, “But I will raise up for myself a faithful priest who will do according to what is in my heart and in my soul; and I will build him an enduring house, and he will walk before my anointed always.” This is the position Zadok will hold under David.

Thus, Samuel, the antithesis of the sons of Eli and the one who confirms the message of judgment on the dynasty of Eli (3:12-14), also anoints David. Both the Davidic dynasty and the Zadokite priesthood are established. The writer of 1-2 Samuel is showing his readers how God’s purposes through David were worked out decades before he came on the scene.

The place of Saul in the argument of the books seems to be transitional—not from judges to a monarchy, but from judges to David. Saul, as a member of the now insignificant tribe of Benjamin, was probably selected as the least threatening possible king of the tribes. His task was designated as attacking the Philistines (1 Sam 9:16), a task completed by David. A deliberate contrast is made between Saul and David from 1 Samuel 16 on (note the juxtaposition of the Spirit of the Lord on David and away from Saul in 1 Sam 16:13, 14). All of first Samuel is leading up to David becoming king in 2 Samuel.

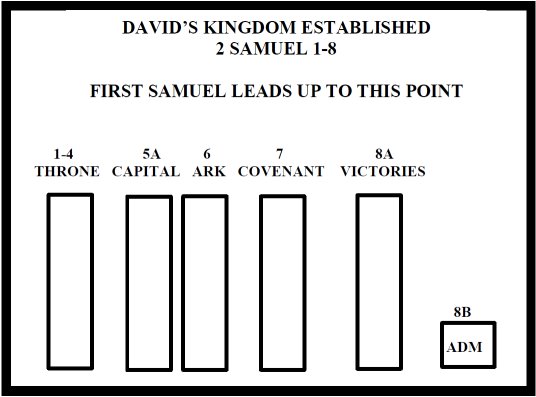

The first eight chapters of 2 Samuel represent the apex of David’s reign. These events did not transpire in a short time; they occurred throughout David’s reign.7 Consequently, this unit is designed to show that God blessed David’s reign and fulfilled His promises to him. The first four chapters are devoted to showing how David, through patience and wisdom, came to rule over all twelve tribes of Israel. Two important events are listed in chapter 5: the selection of the Jebusite fortress for the capital and the defeat of the Philistines. Chapter 6 records the movement of the ark to Jerusalem making that the site of the central sanctuary. Chapter 7 gives the all-important Davidic covenant which will form the basis of God’s future dealings with the descendants of David. Finally, chapter 8 lists the many surrounding small states David defeated. This chapter closes with a list of David’s administrative cabinet showing that the kingdom is established (cf. the same type of list at the end of chapter 20 showing the reestablishment of the kingdom).8 The following chart shows how First Samuel is laying the groundwork for 2 Samuel 1-8.

Once the kingdom was established, the writer now wants to develop two themes: (1) the issue of the successor of David who will thus come under the Davidic covenant promises and (2) the development of the temple as the central sanctuary.

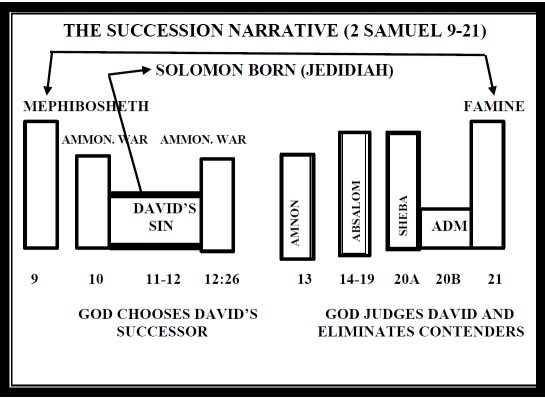

Most commentators speak of the succession narrative and identify it with 2 Samuel 9-20 and 1 Kings 1-2.9 From the author’s point of view, the issue of succession begins in chapter 10. Chapter 9 shows David’s kindness to Jonathan’s son (per their agreement) and is to be compared with chapter 21 where David turns seven of Saul’s family over to the Gibeonites for execution.

Chapters 10-12 form a unit designed to show that God has chosen Solomon to be the successor to David. The Ammonite war brackets the story (10:1—11:1 with 12:26-31). The Ammonites were dealt with in a summary fashion in chapter 8 along with the other surrounding peoples. They are reintroduced here in detail to provide the setting for the sin of David with Bathsheba and Uriah. While this unit gives us much information about several issues, the author draws attention to the fact that the child born from the union of David and Bathsheba was Solomon. Lest there be any question about the relation of Solomon to David, he is the second son born after Uriah’s death. 1 Sam 12:24 says of Solomon: “Now the Lord loved him.” This is the Hebrew way of saying; the Lord chose him. Furthermore, the Lord sends word through Nathan the prophet stating that the other name of Solomon is to be Jedidiah (Yahweh loves). Clearly, then, this unit is designed to show the next successor to David. Furthermore, chapter 7 has indicated that David’s son will build the temple. Thus, Solomon will build it.

The unit from chapter 13 to chapter 20 (1 Kings 1-2 is included in the whole narrative) shows how God judged David for his sin (negative part of Davidic covenant), but also how he eliminated the contenders for the throne who would threaten Solomon. Amnon, Absalom and Adonijah were all from David’s earlier marriages and therefore in line for the throne by birth. Amnon shows his unworthiness to rule and is killed by his brother. Absalom because of rebellion against his father is killed, and finally Adonijah, who decided to “buck the odds,” is killed in a foolish bid for the kingship. The way now is clear for Solomon to rule without opposition.

The final unit in 2 Samuel is chapters 21-24. The literary structure of this unit looks back on David’s victories and forward to the temple. As the chart below shows, there is a chiasm with the Famine in 21 paralleling the plague in 24; the defeat of the Philistines in 21b parallels the heroes of David (who defeated the Philistines). The two middle sections of praise tie the unit together: Chapter 22 praises God for victory over the house of Saul (21a) and over all his enemies (21b). Chapter 23 praises God for the establishment of the kingdom. Chapter 24 speaks of David’s sin in the census, but the outcome of that sin (the plague) is stopped at the very site that will later become the temple. There David builds an altar and sacrifices. Chronicles (1 Chron 21:18—22:2) ties the plague into the temple site. Given the Chronicler’s predilection for omitting David’s sins, the presence of the census/plague is singular and argues for its position in both Samuel and Chronicles as an indicator of the future site of the temple.

Thus, the purposes of God are being worked out through his ḥesed to David, his anointed. David’s seed will be blessed in obedience and disciplined in disobedience. The first “seed” of David will be Solomon whom God chose over his older brothers as David was chosen over his older brothers. To Solomon goes the task of building the temple, but David chose the city and the altar site for its location. Henceforth, the worship of Yahweh in Jerusalem at the temple will be a main issue to the author of Kings. Further the successors of David will be judged in light of the Davidic covenant.

VII. Notes on First Samuel.

A. Samuel, Prophet, Priest and Judge (1 Sam 1:1—7:17).

1. The Birth of Samuel (1:1—2:10).

a. Samuel’s tribal origins (1:1).

First Samuel clearly identifies Elkanah with the tribe of Ephraim while 1 Chron 6:28, 33 places him squarely in the Levitical family. The reason for this is that Levites often became identified with the tribe to which they were ministering. Samuel should be considered a member of the priestly family.10

b. Elkanah’s family struggle (1:2‑8).

Hannah (hypocoristic for “Yahweh is gracious”) was childless: a virtual curse for an Old Testament woman. Peninnah (probably a “precious stone”) had children. Elkanah carried out his responsibility as an Israelite man by going to the worship center at Shiloh annually to sacrifice (actually they were to appear before the Lord three times a year [Deut 16:16], but this was obviously not being obeyed). Shiloh was the place where the tabernacle was pitched after the tribes had settled in the land (Josh 18:1, 8‑10).

Eli and his two sons, Hophni and Phinehas, are mentioned here to prepare for their involvement later. Elkanah’s favoritism is shown by his giving to Hannah a double portion of the sacrificial feast. There was rivalry between the two women, with Peninnah practicing particular cruelty toward Hannah.

c. Hannah’s prayer and vow (1:9‑11).

Hannah resorted to prayer to alleviate her problem. Eli was sitting in his customary place where he could observe the worshippers. Hannah told the Lord that if he would answer her prayer and give her a son that she would devote him to the Lord “all the days of his life and a razor shall never come on his head.” This clearly was a dedication of her son as a Nazirite (Num 6:13‑21) though the text does not call him that. A fragment from Qumran (4QSama) has a phrase at 1:11 and 1:22 not found in either the MT or LXX that says, “And I will dedicate him as a Nazirite forever, all the days of his life.”

d. Eli’s misunderstanding of Hannah (1:12‑18).

It is a sad commentary on the spiritual state of affairs that Eli would assume a worshipper to be drunk because she was moving her lips in prayer. It is to Eli’s credit that he rebuked her. Hannah’s defense was that she was not a worthless woman (Hebrew: בַּת בְּלִיַּעַל bath beliyy’al). This phrase will be used to describe the sons of Eli later (2:12). Recognizing the integrity of Hannah, Eli dismissed her with his blessing.

e. Hannah’s prayer answered (1:19‑20).

Yahweh remembered Hannah, and she bore a son and named him Samuel. The reason for the name, she said was “because I have asked him from the Lord.” The name Saul (Heb.: שָׁאוּל Ša’ul) means “asked one.” Samuel (Heb.: שְׁמוּאֵל Šemu’el) ought to mean “Name of God,” or something like that unless it is a reduction of שְׁמוּעְאֵל Šemu‘’el, i.e., “Heard of God.” The latter is probably correct, and she was saying, “I asked for him, and God heard.”

f. Dedication of Samuel (1:21‑28).

The time for the annual trek to the tabernacle arrived, but Hannah refused to go up until she had weaned Samuel, at which point, she promised, she would leave the child in the tabernacle. Elkanah may have been worried that she would not follow through on her vow, and so he said, “Only may the Lord confirm His word” (1:21‑23). The husband was responsible to approve or annul his wife’s vows (Num 30:1f) (1:21-23).

True to her vow, she brought Samuel to the tabernacle when she had weaned him. This was truly a festive occasion (cf. Gen 21:8). She may have nursed Samuel until he was about four (2 Macc 7:27: three years), but even so he was very young to leave at the tabernacle. KJV says she brought three bullocks; NASB says a three‑year‑old bull. Both LXX and Qumran (4QSama) have one three‑year‑old bull and this is probably the correct reading (1:24).

The phrase, “although the child was young” (Heb.: “The child was a child”) is very unusual in Hebrew and looks suspiciously like a form of haplography.12 The LXX has “and the child was with them and they brought [him] before the Lord, and his father killed the sacrifice which he was making annually to the Lord, and she brought the child.” Unfortunately, Qumran has a break in the manuscript at this point, but there is room for this line in the break. Hertzberg, on the other hand, argues for the MT, comparing it with Judges 8:20 where a similar construction appears (1:25).13

This godly woman then surrendered her son to Eli and explained to him that she was the woman who had prayed for a son and who had vowed to give him to the Lord all the days of his life. What an example! (1:26-28).

g. Hannah’s psalm of thanksgiving and praise (2:1‑10).

One of the most beautiful psalms of the Old Testament is this prayer of Hannah. The psalm was probably already in circulation (the mention of the barren having children makes it so apropos to the circumstances); Hannah recited it, and thus it became a part of Scripture. Hannah’s psalm should be compared to Mary’s Magnificat, composed under similar circumstances.

The psalm eulogizes the Lord’s greatness and his graciousness. It shows that God does not always operate as people think he should. He exalts the lowly and humbles the mighty. He strengthens the weak and feeds the hungry. He searches the heart and knows all that each one thinks. He will ultimately set things right and vindicate those who put their trust in him. These themes of the psalm will be worked out in the lives of the characters of these books.

2. The Family of Eli (2:11—4:22).

a. The writer’s purpose.

The purpose of this section is to contrast the godly life of Samuel with the ungodly life of Eli’s two sons (Samuel now ministers at the altar) and to show why God removed the family of Eli from the priesthood.14 Eli seems to be a good man. He was concerned about the life of the people as evidenced in the way he dealt with Hannah. Yet, he was weak, lacking the fortitude to discipline his own sons. Therefore, he suffered the consequences personally, and the people nationally.

b. The practice of Eli’s sons (2:12‑17).

The character of Hophni and Phinehas is indicated by the fact that they “did not know the Lord.” This means that they had no regard for him. They were totally selfish in their thoughts and conduct (2:12).

They were also called “worthless” men. This is the same phrase (בְּנֵי בְלִיַּעַל bene beliyy’al) Hannah uses in denying Eli’s charge. The word in 2 Cor 6:15, Belial, is from this Hebrew word. It means first to be worthless and then it refers to the most worth-less of all creatures: Satan. The character of these men is demonstrated in the way they treated God’s people who came to sacrifice. They chose whatever meat they wanted, disregarding the normal practices decreed by the law of Moses (2:13-17).

c. The contrast of the boy Samuel (2:18‑21).

Samuel served as a little priest, and his mother provided for him annually. Whenever Elkanah and Hannah came to Shiloh, Eli would bless them. God’s blessing in their lives was evident in the birth of five children. God’s intervention in history to bring this little boy into the world was no little thing. He was raising up a very significant person to carry out his divine will for Israel. The boy Samuel grew before the Lord (as the sons of Eli failed to know or obey the Lord).

d. More on the wickedness of Eli’s sons (2:22‑26).

The women “who served at the doorway of the tent of meeting” seem to be housekeepers or some other such maintenance people (cf. Exod 38:8), (the word “served” is related to Sebaoth (צְבָאוֹת) which usually refers to an army or some other such organization). One can only wonder whether the conduct in 2:22 may involve Canaanite cult practices. Eli protests their wickedness to no avail (2:23‑25). God’s purpose is given in 2:25, but like the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart, human responsibility should be seen prior to the judgment. The contrast of Samuel’s life to Eli’s sons is given in v. 26. The similarity of this statement to the one made of Jesus in Luke 2:52 is not accidental.

e. Prediction of judgment on Eli’s house through a prophet (2:27‑36).

God sent a man of God (a prophet) to tell Eli that in spite of the fact that he held an elect position as a member of Levi’s family, God was going to judge his house because of the crass disobedience of Hophni and Phinehas (2:27‑30). The destruction of the family would not be complete, but they would lose their privileged position. Furthermore, both Hophni and Phinehas would be killed on the same day. In addition, God promised to raise up a faithful priest who would walk before God’s king forever.

The implication of this message is that Samuel would take the place of Eli, as he indeed did, acting as priest‑judge. But Eli’s house was not to be totally destroyed, only demoted. Several years later, the tabernacle was at Nob and Ahimelech, a descendant of Eli, was ministering as high priest (1 Samuel 21, cf. 14:3 also). The entire family, with the exception of Abiathar, was wiped out. Later (1 Kings 2:26‑37), Solomon dismissed Abiathar to his village of Anathoth and replaced him with Zadok who became the “faithful priest.”

f. Prediction of judgment on Eli’s house through faithful Samuel (3:1-21).

The situation out of which the prophecy arose was that Samuel was ministering in the tabernacle (lighting lights, running errands). God’s word was rare, visions were infrequent (this means that there were few prophets). Eli was sleeping (in the adjoining buildings to the tabernacle?). He was old and going blind. The ceremonial lights were still burning. Samuel was also sleeping in the adjoining rooms. The Lord called to Samuel three times. Samuel assumed that it was Eli. Eli finally discerned that it was Yahweh calling and he instructed Samuel to respond: “Speak Lord for your servant hears.” Samuel and Eli’s sons are again contrasted. Eli’s sons did not “know the Lord” in the sense that they did not obey him. Samuel has not yet had such an opportunity, but it has now come, and he responds affirmatively.

The revelation is given (3:10‑14) because the servant responds in obedience. This message is that God will judge Eli’s house. It is an “ear tingling” word of judgment. All previous promises will be carried out. Eli is held responsible for his sons’ conduct. (“Brought a curse on themselves”—this is a correction of the scribes, Tiqun Sopherim, designed to prevent the text from saying, “they cursed God.” Cf. LXX: “Because his sons were cursing God.”).15

The revelation was communicated only at Eli’s insistence (3:15‑18). Samuel was afraid to tell the revelation, but Eli adjures him to tell all, and so he does. Eli as a man of God accepts the judgment of God as just. A crescendo of judgment was reached in Samuel (1) Eli rebukes his sons (2) a prophet rebukes Eli (3) Samuel relays God’s rebuke.

The prominence of Samuel is shown again by the statement that he grew spiritually and God blessed him (3:19‑21). All Israel knew that Samuel was a prophet.16

g. The Judgment of God against the house of Eli begins (4:1‑22).

Contrary to a number of scholars,17 this is not an independent story of the ark originating separately from chapters 1‑3. Though Samuel is not mentioned (he was too young to be involved in the war), it shows the fulfillment of the threat to Eli’s sons (predicted through Samuel) and God’s faithfulness to his covenant represented by the ark.

The Philistine threat, so prominent in the book of Judges rears its head again in Samuel. The chapter begins with the statement that Samuel’s word came to all Israel. That is in the capacity of judge, people from all over came to respect this man of God to whom God revealed himself. The Philistines gathered at Aphek which lies just north of Philistine territory. The Israelites mustered at Ebenezer (a proleptic name, since it will be called “stone of help” after the defeat of the Philistines in Chapter 7) (4:1-2).

The Israelites were soundly defeated in the first foray. About 4,000 were killed. The defeat called for self-examination. The elders concluded rightly that God had allowed the defeat, but they concluded wrongly that the ark of God could be used as sort of a talisman to ward off the enemy. Perhaps they thought they could replicate the battle of Jericho. Thus, the purposes of God were worked out in the judgment against Hophni and Phinehas. The ark was brought into the battle with Eli’s two sons in attendance (4:3‑4).18

Of course, this abuse of the ark only brought a second defeat by Philistines (4:5‑11). The Philistines were frightened at first when the ark entered but rallied to defeat the Israelites (4:5‑10). (Note: The Philistines knew how God delivered Israel from Egypt [4:8]. This makes the defeat doubly bitter and shows that God will not defend even His own people when they are disobedient.)

The ark of the covenant was captured, and the sons of Eli were killed as prophesied in 2:34. The report of the battle eventually came to Eli (4:12‑18). Eli’s great concern was for the ark. Eli was ninety-eight years old and virtually blind (cataracts?). At the news of his sons’ death, but especially at the news of the capture of the ark, Eli fell from his bench and broke his neck. This is a powerful lesson for anyone in spiritual leadership.

Phinehas’ wife went into labor at the news of her husband’s death. She called her new son Ichabod (אֵי כָּבוֹד ’ey kabod lit.: “Where is the glory”). The loss of the ark symbolized to her that God was absent from Israel since the shekinah glory represented his presence. This is the final commentary on the results of disobedience to the divine law (4:19-22).

3. The evidence of God’s continued grace in the protection of the ark of the covenant (5:1—7:2).

a. The vicissitudes of the ark are recounted in chapters 5 and 6.

The purpose in this section is to show that the ark of the covenant, a symbol of God’s presence among the people, cannot be abused by either the Israelites (talisman) or the Philistines (triumph over a national god). God shows them that a proper attitude toward him (represented by the ark) brings blessing (the men of Kiriath Jearim, 7:1).19

b. Confrontation between paganism and Jehovah (5:1‑12).

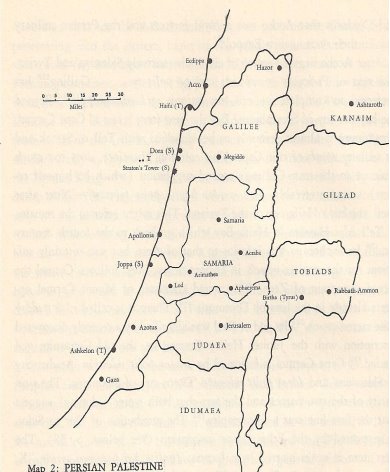

The ark was first brought to the temple at the ancient Philistine city of Ashdod and placed in the temple of Dagon. This deity was once thought to be a fish god (Heb.: דָּג dag = fish) worshipped by the Aegean Philistines. We now know that Dagon (Heb.: דָּגָן dagon = grain) was a deity in the Canaanite pantheon. The presence of the ark brought judgment on the pagan divinity Dagon (1‑5) 20 and on the people (6‑12). As a result, the ark was taken to three cities in the Philistine pentapolis (see atlas). The Ekronites insisted that the ark be returned to Israel (5:11‑12).

c. The restoration of the ark with recognition of the position of the God of Israel (6:1‑20).

The diviners suggested a return of the ark with a guilt offering (Heb.: אָשָׁם ’asham, Leviticus 5). This offering recognized a trespass against God (6:1‑3). The guilt offering was to consist of golden replicas of the tumors and mice—one for each lord/city of the Philistines.

The cows made their way to the border town of Beth Shemesh. The Beth Shemeshites were Israelites. They rejoiced when the ark was returned, and the Levites offered sacrifice. The offering is recounted (6:17‑18), and the statement is made that the stone on which the ark was placed was still there in the time of the author. The Beth Shemeshites profaned the ark by following idle curiosity and looking into the sacred box.22 God judged them by destroying 50,070 men.23 The Beth Shemeshites came under the same wrath as had the Philistines. Instead of acknowledging that they were responsible, they complained about the inapproach-ability of God (6:19‑20).

The men of Kiriath-jearim (Forestville) were not priests, nor was Kiriath-jearim a priestly city. This city was chosen probably because it was near Beth Shemesh. Aminadab was surely a Levite, or his son Eleazar would not have been consecrated to supervise the ark. A larger question is why the ark was not taken back to Shiloh. The answer may lie in the fact that the city was defeated and possibly the tabernacle destroyed (cf. Jer 7:12).24

The relation of this unit to the structure of 1‑2 Samuel should not be missed (see Hertzberg). Here the ark is lost and returned. In 2 Samuel 6 David brings it to Jerusalem and in 2 Samuel 7 he plans to build the temple. 2 Samuel 24 provides the place for the sanctuary.25

d. Defeat of the Philistines (7:3‑17) (The right approach to battle).

There is no indication as to when this event took place. A contrast is being drawn between Samuel’s spiritual life and leadership with that of Hophni and Phinehas in chapter 4 (7:3‑4).

The first criterion to success is a repentant heart. (“Return to the Lord with all your heart.”) This will be evidenced by the renun-ciation of paganism: the removal of the Ashtoreth (fertility goddess) and Baal (storm god). Baal means “master” or “Lord” and was once used of Jehovah (cf. the word Beulah—married—in Isa 62:4). Because of the problem of syncretism, the name was dropped and Bosheth (shameful) was substituted (cf. Ishbosheth, Mephibosheth). Wondrously the Israelites repented and followed the first commandment of the covenant by “having no other gods before them.”

Samuel prepared Israel further by bringing them to Mizpah (watch point), one of his “circuit” cities and famous even in later times (Jeremiah 40; 1 Maccabees 3). They poured out water as a libation, fasted, repented, and Samuel judged them. Normally, “to judge” means to adjudicate disputes. Here it must mean that they confessed their wrongs. Samuel thus continued the tradition of judgeship so well-known already in Israel (7:5‑6).

The Philistines assumed that the Israelites were preparing for war and began to muster their troops. The Israelites were afraid and begged Samuel to pray for them. In response, Samuel offered up a whole burnt offering and prayed for God to deliver them. God’s response was to bring confusion to the Philistines allowing the Israelites to defeat them. Israel was poorly armed. Only prayer and the answer of God in direct intervention could save them. This was the war of Yahweh, not the war of his people. As such, he won decisively (7:7‑11).

After this great victory of Yahweh, Samuel erected a cairn to commemorate the victory. “Even” means “stone” and “Ezer” (as in Ezra) means “help” (אֶבֶן הָעֵזֶר ’ eben ha’ezer). This battle was decisive: The Philistines were subdued, and many of the former Israelite cities were restored. (The Philistines were not finished, of course, for they still must be defeated by Saul and David) (7:12‑14).

This major section is concluded with a summary of Samuel’s ministry. He was a judge. This is proven by his work at Mizpah. He acted as one of the judges in the book of Judges, but he loomed larger than any of them. As a matter of fact, he was more like Moses, and was included with him in Jer 15:1 (where the stress is on intercession). He conducted his ministry in various cities of southern Israel much like a circuit preacher. Bethel, Gilgal, and Mizpah were the three chief centers. No further mention is made of Shiloh, nor is he connected with the ark at Kiriath-jearim. His home was in Ramah (7:15‑17).

B. Samuel and Saul, a time of transition (8:1—15:35

1. The people’s choice: a monarchy rather than a theocracy (8:1‑22).

a. The Problem—Samuel’s sons (8:1‑3).

It is ironic that Samuel’s sons turn out to be unspiritual and un-worthy just like Eli’s sons. One would think that Samuel would have profited from the bad example of Hophni and Phinehas, but he apparently did not. Nothing provokes people like injustice. Because of the perversion of their office, (perhaps exacerbated by the Philistine threat) the sons of Samuel caused the people to look for a king.

b. The request of the people (8:4‑18).

The blunt request of the elders must have been a shock to Samuel. “You are old, your boys are bad, and so we need a king.” Samuel turned to the Lord who told him that it was not Samuel who was being rejected, but the Lord himself. Critics see in this section an ambivalent attitude toward the idea of a kingship which continues as a tension throughout the historical period. The “Deuteronomist,” they say, is opposed to the idea of a king and so inserts his theology into the narrative.26 But God often allows people to choose the second best (“He gave them the desires of their heart and sent leanness to their souls”). In the case of the monarchy, he even chose to bless it by selecting David as the predecessor of the Messiah. God told Samuel to listen to the people and select a king for them. Implicit in this statement is the divine sanction of the monarchy. However, he first told Samuel that he must warn them of the consequence. Israel wanted a king “like all the nations.” Israel was unique in her leadership. The other nations: Egypt, the Hittites, Mitanni, Assyria, Babylonia, Tyre, Sidon, Moab, and Philistia all had a highly developed office of king. Samuel rehearsed to the people all that this king would do to them. These practices were all followed by subsequent kings. Solomon especially overtaxed the resources of the people so that they finally revolted against his son Rehoboam. Samuel also told them that they must be prepared to suffer the consequences, for God would not listen to them in the day they cry out to Him for deliverance from an oppressive king.

c. The response of the people (8:19‑22).

The people, as is often the case, traded the present for the future. Perhaps their greatest fear was to go out to war without a proper leader. Their experience in battle against the Philistines under Eli left them worried, and even the victory under Samuel did not offset their fear. They wanted a king to lead them into battle.

The Lord yielded to their desire and permitted them to have a king. Samuel sent the people away in anticipation of a future appointment. Now the stage is set for the transition from a simple, ad hoc judgeship directly under God, to a complex monarchy that will bring much grief to the people. We are now ready to be introduced to the enigmatic Saul.

The importance of this unit cannot be overemphasized. Moving from the leadership of judges to a monarchy was as significant for Israel’s history as the destruction of the first temple. Not only would the political structure be forever altered, but God’s covenant also would soon be made with David, giving theological direction to the course of Israel’s history unthought-of before the monarchy.

2. The selection of Saul as King (9:1—10:27).

a. Background of the story (9:1‑4).

The genealogy. The tribe of Benjamin was involved in the civil war of Judges 19‑21 which resulted from the sordid affair of the Levite concubine. The Benjamites were virtually decimated. This may account for the choice by God of this tribe: it was less of a threat to the rest of the tribes. (Saul of Tarsus, of course, was from this tribe and was named after the first king.)27

Saul’s father was Kish of Abiel of Zeror of Becorath of Aphiah. Kish was a “mighty man of valor” (גִּבּוֹר חַיִל gibbor ḥayil) usually a Hebrew idiom for an outstanding soldier but used of Boaz (Ruth 2:1) to mean “sturdy” that is wealthy man. So, it should be understood here.

Saul ben Kish is described as a choice young man, very hand-some and tall. This may have led Samuel to look for a com-parable person to replace Saul (1 Samuel 16). However, God told Samuel not to look on the outward appearance.

The immediate circumstances leading up to the story were that some of Kish’s donkeys were lost and Saul and his servant had been looking for them without success.

b. The circumstances for the encounter with Samuel (9:5‑10).

Saul suggested that they return home because they had been gone so long that Kish would be worried about them. The servant suggested looking up the “man of God” in a nearby city to ask about the lost donkeys. The city was no doubt one of the circuit cities (1 Sam 7:16‑17). This indicates that in the popular concept, prophets were thought of almost as “crystal ball gazers.” As a matter of fact, the editor informs us that in earlier times the prophet was called a “see‑er.” (This editorial aside indicates that this part of the book is being written quite a bit later than the events in it.) Furthermore, the “seer” had to be paid for his services. Saul happily acceded to the servant’s advice, and they set out to the city to find the seer.

c. The arrival of Samuel at the city (9:11‑14).

Saul and his servant climbed the entrance slope to the city where they encountered girls leaving to draw water. The girls told them the seer had already arrived to carry out his priestly function in the “high place.” The high place was a cult center where either Jehovah or the pagan gods could be worshipped.28 Later, because of their identification with paganism, the high places were removed. Here it is legitimate as a center for the worship of the Lord.29 On the way to the high place, their paths crossed that of Samuel. All of these circumstances were being divinely engineered to bring about the anointing of Saul.

d. The amazing encounter with Samuel (9:15‑21).

God had already revealed to Samuel that the promised king of chap. 8 would appear on this particular day. This man would become a “prince” (נָגִיד nagid) over “my people Israel” (cf. David in 2 Sam 5:2). His task would be to deliver Israel from the Philistines. This deliverance was God’s response to the cry of the Israelites.

When Saul and his servant appeared, God told Samuel that this was the man of whom he had spoken. At Saul’s query on the location of the seer’s house, Samuel identified himself and invited Saul to join him at the feast connected with the sacrifice. He promised to release him the next day after telling him all that was on his mind. Samuel then gave to Saul a confirmatory sign authenticating his ministry by telling him about the donkeys even before Saul asked about them. (Cf. Jesus and Nathanael—John 1:47‑51.) Saul gave a very humble response, similar to that given by Gideon when God called him to a similar task in Judges 6.

e. Samuel and Saul at the sacrificial meal (9:22‑24).

Samuel took them to the feast and seated them in the place of honor and ordered the choice piece of meat he had asked the cook to set aside just for this occasion.30 The “appointed time” indicates that God was providentially working in this situation.

f. Preparation for the anointing of Saul (9:25‑27).

Samuel and Saul went down from the high place to the city to a house. (If the city were Ramah, the house would probably be Samuel’s. If it were some other, as it seems to be since Samuel was invited to the feast, the house would belong to someone else.) The Hebrew sequence of events is a little awkward:

He spoke with Saul on the roof top

They arose early

Daybreak came and Samuel called to Saul on the roof

The Greek text (B) has:

They spread (a bed) for Saul on the roof top

He lay down

Daybreak came, and Samuel called to Saul on the roof

The difference between “speak” dbr and “spread” rdb is a matter of inverted letters. The Hebrew words for “rise early” škm and “lie down” škb are very similar also.

MT וידבר עם שׁאול על הגג וישׁכמו wydbr ‘m šaul ‘l hgg wyškmu

LXX): וירבדו לשׁאול על הגג וישׁכב wyrbdu l šaul ‘l hgg wyškb (retroverted

Consequently, the LXX probably has the better reading. “And they spread for Saul [a bed] on the roof top, and he lay down.”

Samuel told Saul to send his servant ahead so that he might reveal to him the word of God (9:27).

g. The private anointing of Saul (10:1‑8).

The first anointing of Saul was done by Samuel with no one looking on (10:1). There was a public anointing later.31

So that there will be no question in Saul’s mind about the validity of this anointing, Samuel gave confirming signs (10:2‑7). (Can you imagine Saul’s bewilderment? There has never been a king in Israel; he had never met Samuel before; he was a simple country man looking for his donkeys—and he is told he is to be a king.)

The signs are: (1) Saul will meet two men near Rachel’s tomb (near Bethlehem) who will tell him about the donkeys. (2) Saul will meet three men going up to (worship) God in the cult center of Bethel. They will share their food with him. (3) Saul will meet a group of prophets whom he will join and begin to prophesy.32

Saul was then told to go to Gilgal where he was to wait seven days for Samuel who would come to offer sacrifices and give Saul more instruction (10:8).33

h. The fulfillment of the signs (10:9‑13).

Saul became a new man as he left Samuel. How are we to interpret this statement? Does it refer to salvation? It means at least that God performed a supernatural work on Saul so that he would be different in the future.

The most significant evidence of the change in Saul was the third sign, when Saul joined with the group of prophets in prophesying. Saul’s character apparently was so changed that the people were surprised to see him among the prophets, and his presence even created an aphorism: when someone acted in a way that was out of character, some wag would say, “Is Saul also among the prophets?” The phrase “Now who is their father” probably means that each prophet received his own call and did not enter the prophetic office by birth. Hence, even Saul could join the group though his father was not a prophet. (Saul’s action in 19:22ff. called up the same aphorism.)

i. Saul’s reception at home (10:14‑16).

Saul explained only that they went to Samuel for help in finding the lost donkeys, refusing to satisfy his uncle’s curiosity by telling him more about Samuel.

j. The public anointing of Saul (10:17‑27).

Samuel had anointed Saul privately, but it was now necessary to present him to the people. Instead of simply saying that he had anointed Saul, Samuel used the lot as an evidence of divine choice of Saul. Samuel brought the people to Mizpah for the anointing of Saul as he had brought them there for judging in chap. 7 (10:17).

After delivering a rebuke to the people for asking for a king, Samuel used the lot to select the tribe, family and individual who would be king. Saul was chosen, but he shyly hid in the baggage from which the people took him after God told them he was there (10:18‑23).

Samuel then proudly presented Saul to the people. He took a fatherly interest in Saul from that time forward. The people excitedly accepted Saul as their king, and Samuel went home after giving the people a list of things to expect from the king (10:24‑25).

Saul also went to his home followed by a band of loyal adherents in whom the Lord had worked.34 Of this new king Wright says: “Saul was no wealthy, learned

3. The first test of the new king (11:1‑15).

a. The provocation (11:1‑5).

Nahash, King of the Ammonites, besieged the Manassite city of Jabesh-gilead.36 Frank Cross tells us of a fragment of Samuel from Qumran which has a paragraph not in the MT nor in the LXX (though it is reflected in Josephus and the last phrase of chapter 10).37 “But he kept silent” [ וַיְּהִי כְמַחֲרִישׁ wayehi kemaḥrish] is translated in LXX as “And it came about after about a month” [ וַיְּהִי כַחדֶשׁ wayehi kaḥodesh]. Nahash had recaptured some of the cities taken by the Reubenites and Gadites and mutilated the inhabitants. When 7,000 men fled to Jabesh‑gilead, Nahash laid siege to the city. This data would help explain the reason for Nahash’s attack on Jabesh-gilead and his demand that they put out their right eyes. Some take this paragraph for a Midrashic addition, but Cross argues rather well for its genuineness. If it were lost, it would have been lost by haplography (Nahash . . . Nahash).

The Jabesh‑gileadites persuaded the Ammonites to give them time to seek help. Apparently Nahash was fully confident of his superiority and granted it. The elders sent to Saul for help.

b. The response of Saul (11:6‑11).

Saul came home from plowing (note what this indicates about the kingdom of that time) and heard the report. The Spirit of God “came upon Saul mightily.” The Hebrew word translated “came upon mightily” is tiṣlaḥ (תִּצְלַח). It normally means “to advance” and will most commonly be translated “to prosper.” In this instance it means to “move on someone strongly.” Used of the Holy Spirit coming on men, it is applied to Samson (3x’s), Saul (3x’s) and once to David. The same word is used of the evil spirit coming on Saul (once). Saul summoned the army of Israel with the dramatic act of cutting the oxen into pieces. He mustered 330,000 people, attacked, and devastated the Ammonites.

c. The new respect for Saul (11:12‑14).

The “worthless men” of chap. 10 were threatened, but Saul spared them. Samuel took Saul and the people to Gilgal to renew the kingdom. The people happily accepted Saul as the king over Israel.

4. Samuel’s testimonial (12:1‑25).

a. Samuel calls for a testimony of his pure life (12:1‑5).

The transition has now taken place. Samuel will continue to act as a prophet of God who is actually over the king. This precedent will be continued throughout the monarchy. The king may kill the prophet, but he can never destroy the prophetic office, and prophets will continue to challenge the king to do what is right before God. Samuel called the people to bear witness to his conduct.38 The corruption of public office included theft, fraud, oppression, and bribery. The people testified that Samuel’s life had been above reproach; what a testimony!

b. Samuel’s farewell message (12:6‑18).

Samuel rehearsed God’s acts in history to remind them that they had sinned in asking for a king and to challenge them to a life of obedience in the future. This practice is typical of the teachers in Israel—cf., e.g., Stephen’s sermon in Acts 7. The word “plead” in this form (v. 7) (Heb.: אִשָּׁפְטָה ‘iššapetah) means to enter into a court case with someone.

Samuel recounted God’s deliverance of Israel from Jacob to the most recent situation with Nahash (12:6‑12).39 Samuel next turned their attention to the new and first king of Israel and admonished king and people to follow the Lord (12:13‑17). Samuel then called on the Lord for a miracle which was given to authenticate Samuel’s ministry (12:18).

c. Samuel prays for the people (12:19‑25).

The people, in fear, asked Samuel to entreat the Lord in their behalf. Samuel gave the people a warm and encouraging message, perhaps the most poignant in the book, promising to pray for them.

5. Saul battles the Philistines (13:1—14:52).

a. One of the purposes for which God raised up Saul was to drive out the Philistines (9:16). This he began to do. Samson had made a slight impact on them, and some victory had been won under Samuel, but their grip was not loosened from the Israelites. Now Saul, and more significantly, his valiant son Jonathan began to make inroads into them. It was David, however, who, once and for all, broke the back of Philistine control over the Israelites.

b. The chronology of 13:1 is very difficult.

The KJV has “Saul reigned one year and when he had reigned two years . . .” but this attempt to solve the problem is syntac-tically untenable. The normal reading would be “Saul was_____years old when he began to reign, and he reigned_____years over Israel.” NASB has “Saul was forty years old when he began to reign, and he reigned thirty‑two years over Israel.” NIV has “Saul was thirty years old when he became king, and he reigned over Israel forty‑two years.” Acts 13:21 seems to indicate 40 years for Saul’s reign. Some would argue that the 40 years in Acts includes Samuel’s time. We will

c. Saul decided to attack the Philistine garrison which was the reason he kept only 3,000 troops. The Philistines reacted strongly to the defeat of one of their garrisons, and Saul returned to Gilgal. The Philistines mustered a strong army and many of the Israelites began to flee the country (13:2‑7).

d. Saul violated the word of God which had been given by Samuel to Saul.41 The result is the promise that God will not allow the kingdom of Saul to endure (13:8‑14).

e. Samuel left, and Saul had only about 600 men, and the Philistines sent out raiders who were probably instrumental in disarming most of the Israelites (13:15‑18).

f. The statement in 13:19‑22 is difficult in light of the fact that Israel has won wars against the Philistines and against Ammon. The answer must be that Israel was probably not that well-armed to begin with, and the disarming in recent times had left them poorly armed (which is probably the significance of the phrase “neither was there sword or spear found in the hands of any of the people”).

g. Jonathan performs a brave deed and defeats another Philistine garrison (14:1‑15).

This act of Jonathan was one of great faith and showed him to be a spiritual man, and like David later, in contrast with his father. God supernaturally intervened and caused consternation among the Philistines which later led to an Israelite victory.

h. There is a regrouping of the Israelites, and they pursue and defeat the Philistines (14:16‑23).

This unit contains some very strange things. First the watchmen saw the Philistines sneaking away, and this could not be ex-plained. Assuming that someone must have done something to cause this, Saul mustered the troops and found Jonathan missing. Then Saul asked Ahijah to bring the ark to help ascertain Yahweh’s will in this matter.43 While the priest was consulting the mind of Yahweh, the noise of the Philistine retreat grew, and they even began to kill one another. Saul, in haste, broke off efforts to communicate with God and began to fight (14:16‑19).

Jews who had apparently allied with the Philistines came over to Saul as well as those who had slunk away when the threat of war came.44 Consequently, the advantage shifted to the Israelites and they won the battle (14:20‑23).

i. Saul makes a rash vow, ordering the soldiers to not eat anything (14:24‑30).

This rash vow was a measure of Saul’s poor leadership. Men in the heat of battle need nourishment. Jonathan ironically fell under the curse; he was the one who caused the victory to begin with.

j. The victory goes to Israel, but the people are so hungry they begin to eat blood with the meat (14:31‑35).

The rash vow of Saul brought the people under a curse since they were so hungry. They fell on the slaughtered animals and were breaking God’s law by eating the flesh with the blood. Saul wisely saved the day by asking the people to bring the animals where they could be properly prepared for food. (Perhaps this offset his foolish act of depriving the people of food.)

k. Saul decides to pursue the Philistines into their own territory, but God does not answer him when he inquires, so he assumes it to be because of some fault (14:36‑46).

Did God withhold an answer to force Saul’s hand in the rash vow? It was Saul’s rashness that has caused the problem. The refusal of the Lord to answer Saul’s request will become a pattern as God’s rejection moves to a climax. The lot fell on Jonathan who answered his father derisively. Saul was determined to kill his son, but the people interceded, and Jonathan was saved.

l. Summary of the remainder of Saul’s reign (14:47‑52).

Saul as the military-judge-king, wars against the surrounding nations of Moab, Ammon, Edom, Zobah, and the Philistines. A roster is given of Saul’s family and administration:

- Sons: Jonathan, Ishvi, and Malchi‑shua

- Daughters: Merab and Michal

- Wife: Ahinoam bath Ahimaaz

- General of the army: Abner ben Ner, Saul’s cousin

- Father: Kish (14:47-51).

A summary statement of the wars with the Philistines is given (14:52).

6. Saul’s second rejection comes with his failure in the ḥerem war against the Amalekites (15:1‑35).

a. God calls for a “total destruction” war (15:1‑3).

The Hebrew word for “totally destroy” in 15:3 is from ḥerem (חֶרֶם). It refers to something consecrated or dedicated to a particular use. It is somewhat similar to the word holy (קָדוֹשׁ qadosh). (In Arabic it refers to the sultan’s wives who are off limits to all other men.) Jericho was to be a “ḥerem” city when Joshua attacked it: its treasures were to be turned over to the sanctuary, and all men, women and children were to be killed (except for Rahab and her family). Achan’s sin was to take some of the spoil (in other cities that would not be a sin for it was not “banned”). Now God called upon Saul to carry out a “ḥerem” war against the Amalekites because of their implacable hatred of Israel.

b. Saul wins the battle but loses the “war” (15:4‑9).

Saul mustered the troops and won a decisive victory over these ancient enemies. However, he made a fatal mistake in capturing Agag alive and preserving a number of the finer animals instead of killing them as he had been instructed. Saul could (as he did) argue that the people were out of hand, but proper leadership could have dealt with the problem in such a way as to avoid God’s wrath. This is a classic example of partial obedience. When so much “good” is accomplished, the human propensity is to justify the “non-good.” In fact, it is disobedience and that to a direct command.

c. God confronts Saul with his sin through Samuel (15:10‑33).