2. Analysis and Synthesis of Exodus

Related MediaThe analysis and synthesis approach to biblical studies applied here to Exodus is a methodology developed by the author (DeCanio, 2007) in conjunction with his doctoral studies at the University of South Africa. An abbreviated version of this work entitled, Biblical Hermeneutics and a Methodology for Studying the Bible, will be posted as an article on bible.org.

The bibliography for this study of Exodus is presented at the end of the article, Introduction to the Pentateuch.

Analysis of the context

Authorship

There are several internal claims in the Book of Exodus which directly ascribe authorship to Moses. He is told to record on a scroll the episode of Israel's victory over Amalek (17:14). He is instructed to write down the Ten Commandments (34:4, 27-29). He "wrote down everything Yahweh had said" (24:4), which included at least the Book of the Covenant (20:22-23:33). These internal claims are supported by a strong association of Mosaic authorship for the Pentateuch found in other OT books and in NT books as discussed in the Introduction to the Pentateuch (see, also, Kaiser 1990:287-288). When all the evidence found in Scripture is considered, along with Moses' qualifications for writing Exodus and the remaining books of the Pentateuch, it is hard to deny the strong likelihood of Mosaic authorship.

Recipients

It would seem that Moses' original readership would have been the Exodus generation of Israelites as well as all future generations who entered into covenant-relationship with Yahweh. While the covenant-relationship is offered to Israel, it is clear from the Book of Exodus that a response of faith is necessary to truly enter into that relationship.

Time period of the historical events and composition

Date of events

The events of the Book of Exodus span from sometime after Joseph had died and a new Egyptian king came to power who did not know Joseph, to the setting up of the Tabernacle at Israel's encampment at Mount Sinai. Now Exodus 12:40, 41 states that Israel had lived in Egypt 430 years to the day when Moses led them out. Further, Exodus 19:1 notes that in the third month after coming out of Egypt, on that very day, Israel came into the wilderness of Sinai. And lastly, Exodus 40:17 says that the Tabernacle was erected on the first day of the first month of the second year of Israel's exodus from Egypt. Thus, Exodus 12-40 spans a period of one year. Now Exodus 2 begins with the birth of Moses which took place about 80 years before the Exodus (7:7). Thus Exodus 2-12 spans about 80 years. It is very difficult to determine how long Israel was in Egypt before they had increased greatly and was viewed as a threat by the Egyptians. Clearly it had to be more than 30 years for that would not have been enough time for such a great multiplication of Israelites to have occurred. A time span of 100 years would be required with an annual growth rate somewhat higher than 5% in order to reach a population expansion large enough to field an army of some 660,000 men. Thus the events in chapter 1 could have spanned a time period of 250-330 years.

A date of 1446 B.C for the Exodus has been supported in the Introduction to the Pentateuch. This would date the birth of Moses at about 1526 B.C. and the erection of the Tabernacle at 1445 B.C. Thus the majority of events recorded in the Book of Exodus occurred between 1526 and 1445 B.C., a time span of 81 years.

Date of composition

Moses’ leadership of Israel began when he was 80 years old (7:7). The date for the composition of the Book of Exodus must, therefore, be between that point in time and when he died just prior to Israel's entrance into the Land of Promise (Deut 34:7). It is reasonable to assume, however, that the one year Israel spent in the wilderness at Sinai would have presented Moses with a good opportunity to write the majority, if not all of Exodus. Taking the date of the Exodus as 1446 B.C., the Book of Exodus could have been written as early as 1445 B.C.

Biblical context

Historical element

The historical context to the Book of Exodus is presented in the first chapter. Israel was in Egypt, Joseph was dead along with all those of his generation, and the new Pharaoh had no idea who Joseph was or what he had done for Egypt. In the course of time Israel had multiplied greatly, in fulfillment of Yahweh's word of promise to Abraham (Gen 13:16), and the Egyptians began to view the sons of Israel as a potential threat to their security. To neutralize that threat, the Egyptians forced the sons of Israel into bondage and made them to serve Egypt with hard labor. But the more that Egypt afflicted Israel, the more they multiplied and spread out over the land.

Socio-cultural element

The socio-cultural context of Exodus has two distinct aspects; from the beginning up to the Exodus, and then from the Exodus to the end of the book. Initially Israel is living in bondage to the Egyptians and subject to their desires. During this time they live in a social community of houses and likely villages perhaps organized around their tribal clans. Although they are subject to harsh labor, they apparently live moderately well having plenty of food to eat.

However, with the Exodus, all that changes. Though they are now free from Egyptian domination, they are now subject to Yahweh. Whereas before they lived in a sedentary way in houses and villages, they are now living in tents and are wandering in the wilderness and then encamped at Mount Sinai. Furthermore, food and water which was plentiful in Egypt are now scarce in both quantity and type, and they are totally dependent on Yahweh to provide everything for them.

Theological element

The theological element for Exodus looks back on Genesis and subsumes all of its theological revelation as its context. However, major additions to this context must be made as Yahweh reveals Himself through His mighty plagues brought against the Egyptians, through the covenant-relationship He proposes to Israel, through His laws specified in the Mosaic Covenant, through His anger and wrath which He brings against Israel for their disobedience to the covenant stipulations, but also through His grace and mercy which He extends to Israel in response to the mediation of Moses.

In addition to the Abrahamic Covenant, the single most dominant addition to the theological context for understanding Exodus is the Mosaic Covenant and the covenant-relationship which it specifies between Yahweh and Israel. This addition to the theological context controls not only understanding Exodus but the rest of the Pentateuch and in deed the rest of the Old Testament. So important is this covenant to Israel’s history that when the New Testament era opens we find Jesus living under it.

Analysis of the text

Broad descriptive overview

|

Chapter |

Descriptive Summary |

|

1 |

Oppression of Israel by the Egyptians |

|

2 |

Moses’ birth and preparation |

|

3 |

Moses’ call by Yahweh to deliver Israel |

|

4 |

Moses' objections to Yahweh's call |

|

|

Moses' submission to Yahweh's call |

|

5 |

Moses' first encounter with Pharaoh |

|

|

Moses calls on Pharaoh to let Israel go |

|

|

Pharaoh’s response |

|

|

Israelites’ response |

|

|

Moses’ response |

|

6 |

Yahweh’ response |

|

|

Genealogy of Moses and Aaron |

|

7 |

Yahweh's commitment to deliver Israel after bringing judgment on Egypt |

|

|

First plague: blood |

|

8 |

Second plague: frogs |

|

|

Third plague: gnats/lice |

|

|

Fourth plague: flies |

|

9 |

Fifth plague: death of livestock through severe pestilence |

|

|

Sixth plague: boils on man and beasts |

|

|

Seventh plague: hail |

|

10 |

Eighth plague: locusts |

|

|

Ninth plague: darkness |

|

11 |

Tenth plague: death of first-born announced |

|

12 |

Institution of the Passover to protect first-born of Israel |

|

|

Death of Egypt's first-born executed |

|

|

Israel’s departure from Egypt |

|

13 |

Institution of dedication/redemption of Israel's first-born males to/from Yahweh |

|

|

Yahweh’s protective presence; cloud by day, fire by night |

|

14 |

Deliverance through the Red Sea |

|

|

Destruction of pursuing Egyptian army |

|

15 |

Song of deliverance |

|

|

Israel's grumbling over bitter water |

|

16 |

Israel's grumbling over lack of food; |

|

|

Yahweh's provision of manna |

|

|

Institution of the Sabbath as a day of rest |

|

17 |

Israel's grumbling over lack of water; the rock struck |

|

|

Israel's defeat of Amalek |

|

18 |

Jethro's counsel to Moses; division of responsibility |

|

19 |

Covenant proposed and accepted |

|

20 |

The Ten Commandments |

|

21-23 |

The laws of the covenant |

|

|

Laws dealing with society |

|

|

Laws dealing with civil and religious obligations |

|

|

Laws dealing with Sabbaths and Feasts |

|

|

Laws dealing with the conquest |

|

24 |

Ratification of the covenant |

|

|

Yahweh's giving of the Stone Tablets |

|

25 |

Yahweh's command to construct a Tabernacle |

|

|

Specifications for the ark and the mercy seat |

|

|

Specifications for the table of bread |

|

|

Specifications for the lamp-stand |

|

26 |

Specifications for the curtains |

|

|

Specifications for the boards |

|

|

Specifications for the veils |

|

27 |

Specifications for the bronze altar |

|

|

Specifications for the court |

|

|

Specifications for the oil for the lamp |

|

28 |

Specifications for the priest's garments |

|

29 |

Specifications for the priest's consecration |

|

30 |

Specifications for the altar of incense |

|

|

Specifications for the atonement money |

|

|

Specifications for the laver |

|

|

Specifications for the anointing oil |

|

|

Specifications for the incense |

|

31 |

Appointment of the craftsmen for building the Tabernacle |

|

|

The Sign of the covenant: the Sabbath |

|

|

Israel's breaking of the covenant through worship of the golden calf |

|

|

Yahweh's anger to destroy Israel |

|

|

Moses' intercession on behalf of Israel; Yahweh's relenting |

|

32 |

Moses' anger toward Israel |

|

33 |

Israel's repentance |

|

|

Moses' intercession on behalf of Israel |

|

|

Yahweh's revelation of Himself to Moses |

|

34 |

Yahweh's renewal of the covenant |

|

35 |

Israel's freewill offerings of the material for the Tabernacle |

|

36 |

Moses' giving of the material to the builders |

|

|

Fabrication of the curtains, boards, veils |

|

37 |

Fabrication of the ark, table, lamp-stand, altar of incense |

|

38 |

Fabrication of the brass altar, laver, court |

|

|

Summary of material given by Israel |

|

39 |

Fabrication of the priestly garments |

|

|

Moses' inspection of the work |

|

40 |

Erection of the Tabernacle by the builders |

|

|

Moses' consecration of the Tabernacle |

|

|

Moses' ordination and consecration of Aaronic priesthood |

|

|

Yahweh's indwelling of the Tabernacle |

Major theological themes

The major theological themes of the Book of Exodus clearly center on the developing concept of covenant-relationship between God and Israel. This relationship is founded first of all in the plan and purposes of God as revealed in part in the Book of Genesis through God's word of decree in creating man in His own image (Gen 1:26-28), in God's word of promise to Adam in cursing the serpent/evil one (Gen 3:15), and in God's word of promise to Abraham (Gen 12:2-3; 13:14-16; 15:4-5, 13-18; 17:1-8; 22:15 -18). It is clear from Genesis that God is calling out an elect people, the seed of the woman, and separating them to Himself to bring them back into relationship with Him, to reestablish His rule through them, to bless them, and to bless others through them. In this context of developing covenant-relationship four major theological themes stand out: (1) promise and fulfillment; (2) the revelation of Yahweh as the sovereign God who rules over nations and peoples and passes judgment on them, as the God of redemption, and as the God of the covenant; (3) redemption; and (4) the covenant and covenant-relationship.

Promise and fulfillment

The Book of Exodus is based upon the fulfillment of Yahweh's promises to Abraham. While fulfillment may not always be complete, the point of theological concern is not to be placed on the degree of fulfillment but on the kind of fulfillment. The following demonstrates promises and/or prophecies that are specified in the Book of Genesis and fulfilled in the Book of Exodus.

The promise of a great nation

A recurring promise that God made to Abraham was to make him into a great nation (cf. Gen 12:2a; 13:6; 22:17). The fulfillment of this promise is seen in Exodus 1:7 which notes, "But the sons of Israel were fruitful and increased greatly and multiplied, and became exceedingly mighty, so that the land was filled with them."

The prophecy of enslavement

In Genesis 15:13 God, in the process of confirming His promises to Abraham through the cutting of a covenant, informed Abraham that while his descendants would surely receive the land of Canaan as their possession, they would be delayed in taking possession of it because they would first be strangers in a foreign land where they would be enslaved and oppressed for 400 years. The fulfillment of this prophecy is recorded in Exodus 1:8-14.

The promise of judgment and deliverance

Although God would permit the enslavement and oppression of Abraham's descendants, He promised Abraham that He will judge the nation whom they will serve, and afterward, in the fourth generation, they will come out of that land with many possessions and return to the land of Canaan (Gen 15:14, 16). The fulfillment of the promised judgment upon the oppressors of Abraham's descendants is recorded in Exodus 7:14-11:8; 12:29-30; 14:23-31. The fulfillment of God's promise of the release of Abraham's descendants is recorded in Exodus 12:31-34; 40-41, 51, and the fulfillment of God's promise that Abraham's descendants would leave the land of their enslavement with many possession is recorded in Exodus 12:35-36.

The significance of these recorded fulfillments of God's promises is to show that God has begun to fulfill His promises to Abraham, and if he has already fulfilled these promises will He not also fulfill the others as well, in particular the promise of the land of Canaan? Thus, these beginning fulfillments create an expectant hope that fulfillment of God's word of promise concerning the land will follow as well.

The revelation of God

The revelation of the person of God is paramount throughout the book. He is the One who controls history (chapter 1); He revealed Himself in a name which, though not new, takes on new meaning (3:14); He is the originator of the covenant and, with it, the covenant-relationship (19:1-5); He is the redeemer of His people (6:6; 15:13); He is judge of His people (4:14; 20:5; 32: 27-28) and of His foes (chapters 7-12); and He is the transcendent One who, though existing outside of the Creation because He brought it into being by the power of His word (Gen 1), nevertheless dwells (tabernacles) among His elect people (29:45-46; 40:34).

The revelation of God through His names

One of the characteristics of the biblical revelation is that it reveals God by His names. Sometimes a name is revealed which is derived from a root term from which a sense of the name's meaning may be determined. The name of God revealed in Genesis 17:1 (and noted in Exodus 6:3) is such an example. There God revealed Himself as El Shaddai (commonly translated as "God Almighty"), a name that is derived from a Hebrew term that means "mountain." Thus El Shaddai portrays God as the "God of the mountain," or "the overpowering One, standing on a mountain."

The name by which God reveals Himself to Moses and to all of Israel in the Book of Exodus is YHWH, pronounced Yahweh, (3:14-15). This name was applied to God in the Book of Genesis but without explanation. The understanding of the four letters written in the Hebrew text has been the subject of much debate. This controversy, however, seems to be over the meaning of the name as determined from etymological implications, that is, based on the implications of meaning from the Hebrew verb "to be," the stem from which the name is derived. Some take it with a present active sense and understand it to mean "I am" referring to God as the active, self-existent One. Others take it with a future sense and understand it to mean "I will be what I will be."

But more important than a meaning derived from its etymological roots are the implications of meaning derived from the context in which the name is revealed. In the context of the Book of Exodus, God, first of all, identifies Himself as Yahweh "the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob." In this there is continuity with God's relationship with Israel's patriarchs and with the covenant promises that He made to them. But the Book of Exodus goes beyond this implication of meaning which was made known through the events in Genesis, to incorporate new traits. That this is so is seen from God's own declaration to Moses, " . . I am Yahweh, and I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, as El Shaddai (God Almighty), but by My name, Yahweh, I did not make Myself known to them" (6:2-3). Thus, although the patriarchs knew the name Yahweh and referred to God by it, they nevertheless did not know its full significance. The Book of Exodus makes that significance known through God's actions with, and on behalf of, Israel. In His relationship with Israel, Yahweh is His memorial-name to all generations (3:15). In the context of the Book of Exodus, the name Yahweh takes on implications of meaning which include redeemer (Israel's go'el, kinsman-redeemer, 3:7-8; 6:2-7), suzerain-king covenant-maker and participant (19:1-6), and the God who dwells (tabernacles) among His people (29:45-46; 40:34).

The revelation of God through His nature

The Bible also reveals God through His nature. In the Book of Exodus God is revealed as compassionate, gracious, slow to anger, abounding in lovingkindness and truth, keeping lovingkindness for thousands, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; yet as punishing the guilty, and visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and on the grandchildren to the third and fourth generation (34:6-7)

The revelation of God through His acts

The Book of Exodus reveals God through His acts as a covenant-maker and keeper, as the sovereign over individuals, nations, and nature, as executing judgment upon the wicked, as a kinsman-redeemer, as a warrior, and as personal, coming to dwell in the midst of His people. Exodus reveals God who acts to execute judgment upon Egypt for the evil it committed in afflicting His chosen people with hard labor and bondage, and for its worshiping false gods. Exodus further reveals God who acts to deliver His chosen people from Egypt, and to bring them into covenant-relationship with Himself. The Book of Exodus reveal God who carries out His actions, first, on the basis of the promises He made to Abraham, and then, on the basis of the Law He stipulated as part of the covenant He made with His chosen people.

The revelation of Yahweh as the sovereign God: The Book of Exodus reveal God who though outside of the Creation nevertheless is involved in and with the Creation. In the beginning of the Book of Exodus God's action is revealed as irrupting1 from outside of history to take affect on behalf of His elect people by calling Moses, effecting judgment upon Egypt, and by redeeming/delivering Israel. With the cutting of the covenant at Mount Sinai, God is revealed as acting sovereignly in history as He localizes His presence on earth in the midst of Israel, first in the pillar of cloud, and then in the Tabernacle.

When Moses and Aaron appeared before Pharaoh, their goal was to secure the release of the Israelites from Egypt. God had heard the cries of His elect people and was going to deliver them from the land of their enslavement. Since Pharaoh would not listen to Moses (5:2), God performed signs and wonders to convince him to let Israel go. These miracles are called "mighty acts of judgment" in 6:6 and 7:4 because Egypt deserved to be punished for she was unprovoked in mistreating the sons of Israel. God had blessed Egypt through Joseph, but later pharaohs took advantage of the sons of Israel without just cause and reduced them to slaves (see, Wolf 1991:132).

Yahweh's judgments on the Egyptian people demonstrate His sovereignty over not only Israel but also over other nations as well. To Israel, this was a demonstration that the One calling them to Himself as their God was not "a local deity" but the one true God who rules over all mankind and over all nature.

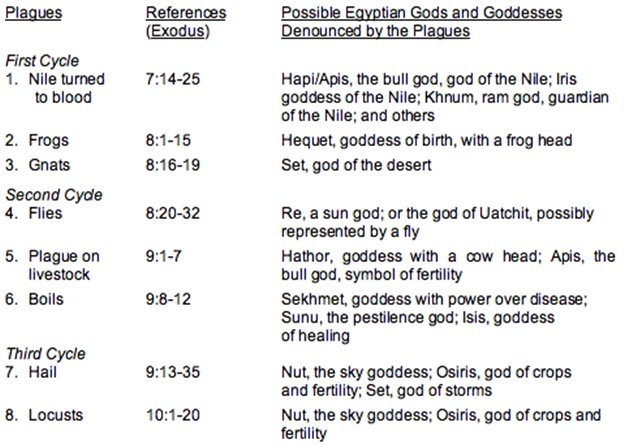

The judgments that Yahweh effected on Egypt may be understood as judgment upon the their gods and goddesses2 as well to reveal their impotence and to show that the God of Israel is the one true God. The following is a summary of the three cycles of judgments and the one culminating judgment (see Hannah 1985:120):

There is an increasing level of intensity in punishment in progressing through the three cycles of judgment, culminating in the most devastating of all, the death of the firstborn. In effecting judgment upon Egypt Yahweh demonstrated His power over all of nature, culminating in His parting of the Red Sea to provide a safe passage for Israel and a place of death and destruction for Pharaoh's army.

The revelation of Yahweh as the God of redemption: The Book of Exodus reveals Yahweh as the God of redemption, the kinsman-redeemer who exercised His powers to perform mighty acts of judgment upon Egypt to redeem His people from their bondage in Egypt. It is Yahweh who hears the cries of Abraham's descendants and takes action to redeem them from bondage, first in calling Moses, then in effecting judgment on Egypt, and lastly in delivering Israel by means of the Passover and the waters of the Red Sea. In all this, Yahweh redeemed Israel, an act that goes far beyond physical deliverance to the very act of spiritual redemption (as discussed below), in order to separate a people to Himself and bring them into covenant-relationship with Himself that He might be their God and they His people.

The revelation of Yahweh as the God of the covenant: The Book of Exodus also reveals Yahweh as the covenant making and covenant keeping God. It was Yahweh's proposal to Israel to enter into covenant-relationship, and it was Yahweh who stipulated the covenant requirements and conditions. Further, after Israel had violated the most fundamental stipulation of the covenant, Yahweh demonstrated His faithfulness to the covenant by responding to the intercession of Moses and continuing with His people (chapters 32-34).

Redemption

The Book of Exodus presents the mighty acts of God by which He effects the redemption of Israel from bondage in Egypt. While the first nine judgments on Egypt "softened Pharaoh's and Egypt's hardened heart" toward letting Israel go, it was the last judgment, the judgment on the firstborn that broke their stubborn resistance to Yahweh's command. In effect, this judgment brought destruction to Egypt's firstborn, while God's provision of the Passover brought deliverance/redemption to Israel's firstborn, and to the nation, as God mediated the judgment pronounced against Israel's firstborn upon the Passover lamb. There is no question that through the death of Egypt's firstborn and the redeeming of Israel's firstborn through the Passover, God effected Israel's physical redemption from Egypt The question is, did He also effect their spiritual redemption?

It is the contention of this analysis that the Passover redemption effected by Yahweh was efficacious not only for Israel's redemption from physical bondage, but also from sin, and that the Passover redemption provided by Yahweh was a type of the true redemption that He would one day effect through Christ for redeeming all mankind from sin. The basis upon which this conclusion is founded rests upon the supposition that the nature of God's purpose in delivering Israel from Egypt mandated the nature of the redemption that He effected through the Passover. The nature of Yahweh's purpose in redeeming Israel from Egypt is seen to be in making Israel:

- His own possession among all the peoples of the earth (19:5);

- a kingdom of priests (19:6a);

- a holy nation (separated to Himself, 19:6b); and

- a people among whom He would dwell (29:45-46)

All these factors imply that the nature, or type of meaning, of the Exodus redemption must necessarily be redeemed from sin.

Although the Passover passage does not explicitly state that redemption from sin is being effected, it becomes clear that the type of meaning expressed in the text has this as a necessary implication. In particular, it is found in the implications of three fundamental redemptive concepts that are later developed in Scripture but used in Exodus to convey the Passover stipulations; they are, (1) lamb as a substitute sacrifice, (2) blood as an atonement for sin, and (3) faith as a necessary response. The demonstration that the type of meaning for the Passover event is redemption from sin is found in a correspondence between these redemptive concepts and the essential meaning of atonement for sin as found in the Book of Leviticus which dictates the need for a substitute sacrifice (Lev 4:1-5:13), the application of the blood which was given by Yahweh to effect atonement (Lev

The covenant

There are three factors necessary for the formation of a nation: a common people, a common homeland, and a common government or constitution holding the people together. Exodus 1-18 records the creation of the people, the Book of Joshua records the acquisition of the land, and Exodus 19 through the Book of Leviticus presents the details of the constitution adopted and entered into at Sinai. This constitution is a covenant binding the people of Israel to Yahweh as their Suzerain King, and binding the tribes of Israel to one another as co-vassals of the King. In effect, when the process is complete—acquisition of a people, constituting of a people, and acquisition of the land—a theocratic state will have been created with all Israelites equal under Yahweh their God (see Johnson 1987).

There are two aspects to the covenant ratified at Sinai; its form and its function which is defined by its stipulations. The form of the covenant is discussed in the Introduction to the Pentateuch where the covenant-treaty presented by Moses was shown to be structured similar to the Hittite suzerainty-vassal treaty form characteristic of that age. The second aspect of the covenant is its function which is discussed here.

Basic function of the covenant

The basis for the covenant-relationship proposed by Yahweh and accepted by Israel's Exodus generation (and later renewed by the Conquest generation, Deut 27) is founded in the concept of a suzerainty-vassal relationship. Yahweh is proposing to enter into a relationship with Israel whereby Israel promises obedience to Yahweh as their King and He in turn promises to treat them benevolently as His own possession among all the peoples of the earth (19:1-5). But there is another dimension to the covenant proposal that has no relationship to the suzerainty-vassal treaty agreements of that day. The relationship God proposed to Israel made them to be His own possession (literally, a special treasure), and a kingdom of priests and a holy nation (19:6). The kingdom relationship God was proposing to Israel was one in which the subjects of the kingdom were all priests with immediate access to Him, and one in which the nation of Israelites were to be a holy nation. While the concept of "holy" includes the idea of being separated, (and indeed, Israel was to be separated from all other nations and devoted only to Yahweh), that separateness was to be defined (as the Book of Leviticus does) in terms that reveal the holiness of God in His separation from all that is evil, profane, and defiling. It is in this sense that Israel was called to be holy, as it says in Leviticus 19:1, "You shall be holy, for I Yahweh your God am holy."

The requirement for Israel to be a holy nation separated to Yahweh is basic to the whole covenant-relationship and a recurring theme in the Book of Exodus (and more so in the Book of Leviticus). The reason Yahweh separated Israel from Egypt and redeemed them was to take them to be His people—they would be His people and He would be their God (6:7-8). It is for this reason that He separated them and brought them to Sinai where He would enter into covenant relationship with them (19:4).

That separation is a basic issue in the Book of Exodus is seen in the demands Yahweh made to Pharaoh that he let His people go that they may serve Him (cf. 4:23; 7:16; 8:1, 20; 9:1, 13); in the Egyptian's recognition that the sons of Israel were being separated from Egypt to serve their God (see, for example, 10:7, 8, 11, 24); in Pharaoh's exclamation that he made a mistake in letting Israel go from serving Egypt (14:5); and in Israel's willingness to go back and serve the Egyptians when their lives were being threatened at the Red Sea (14:12). This is also seen in Yahweh's distinction between Israel and Egypt in bringing judgment upon the land and the people. Israel was protected, while Egypt was judged (see, for example, 8:22-23; 9:4, 26; 10:23; 11:7). Nowhere is there any clearer evidence of this than in the judgment on the first-born where only Israel was given the opportunity to be protected from the destroyer by exercising faith in the blood of the Passover lamb (chapter 12)

The covenant stipulations

The stipulations of the covenant take the form of Ten (somewhat general) Commandments (20:1-17) that form a foundational framework within which the covenant relationships are to be worked out, and a set of specific commands that deal with practical situations in the course of daily living (chapters 21-23).

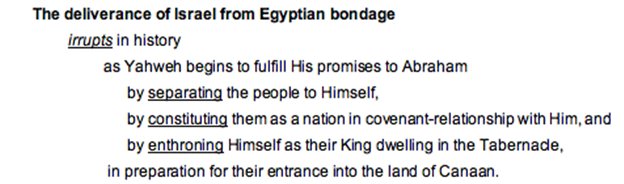

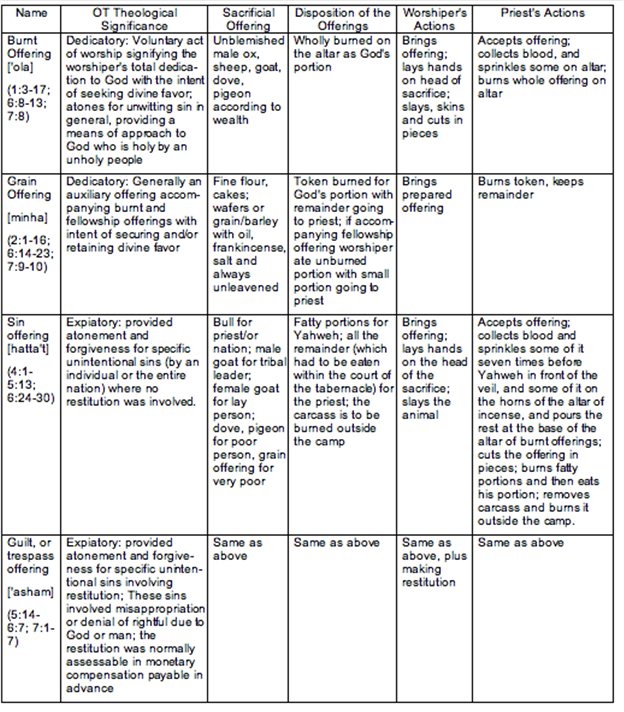

The expression of covenant-relationship through worship

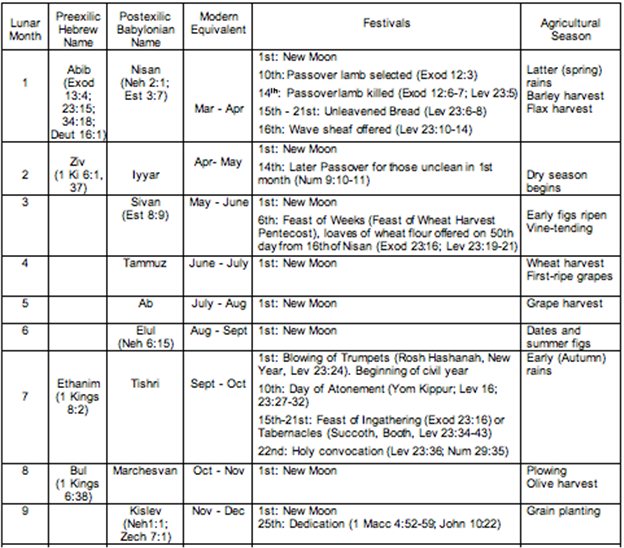

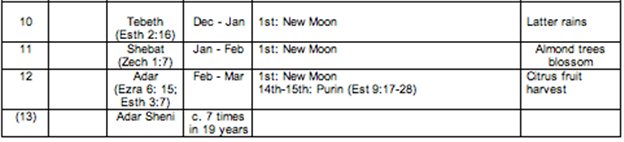

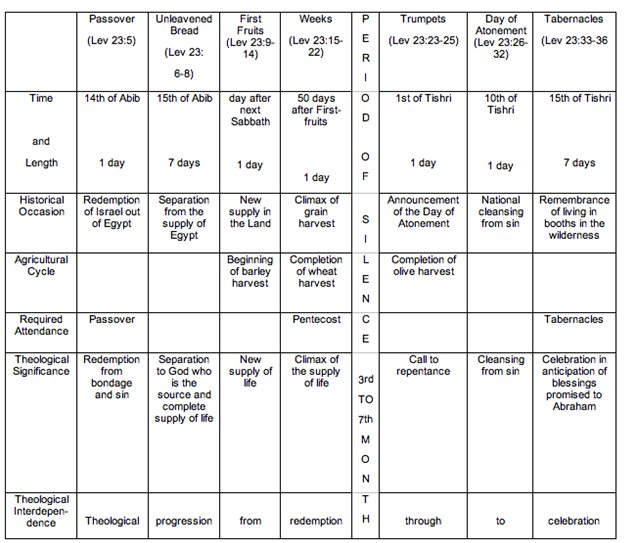

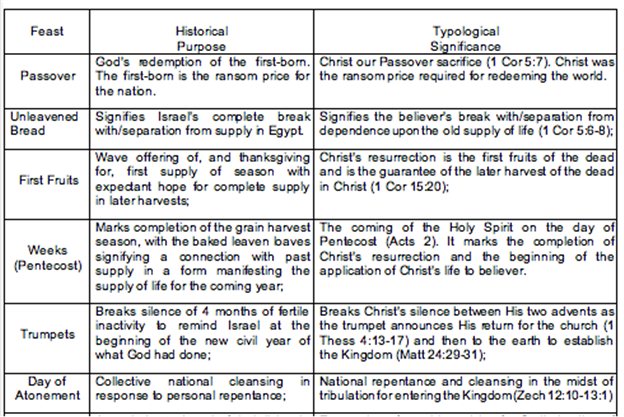

The covenant-relationship is characterized by obedience and benevolence; Israel promises obedience to Yahweh, and Yahweh promises to be benevolent to Israel. But there is another dimension to the covenant-relationship that finds its expression in worship. Israel is commanded to worship Yahweh and Him alone by having no other gods before Him to worship and serve (20:3-5). In order that worship of Yahweh may be expressed properly, and not according to pagan practices, God institutes a system of worship that is centered in the Tabernacle, the place where Yahweh localizes His presence on earth (25:8; chapters 25-27; 30-31; 35-40), that is administered by a priest-hood invested in Aaron and his descendants (chapters 28-29), and incorporates the weekly observance of the Sabbath (31:12-17) and the annual observances of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, the Feast of Harvest, and the Feast of In-gathering (23:10-19), as well as the yearly observance of the Passover (chapter 12)

Literary characteristics

The literary characteristics of Exodus are considered in terms of its literary structure. The literary structure of the Book of Exodus has been shown in the Introduction to the Pentateuch to be somewhat dependent upon the form of a suzerainty-vassal treaty. While it is important to recognize the components of this treaty in the text of Exodus in order to understand the theological message that Moses is developing, the form of the treaty does not dictate the structure of the message. To see this, it is helpful to have in mind an overview of the book.

In the Book of Exodus, Moses instructs the sons of Israel as to their national origins by narrating the formative events in the beginnings of their national history, namely, their redemption from bondage in Egypt to a people free to serve Yahweh, and their covenant-relationship with Yahweh which is the constitutive basis for their national political and religious origins, and by stipulating the terms of the covenant-relationship in the bilateral form of a suzerainty-vassal treaty, and in legislative language which details the social and religious responsibilities of the people within that covenant-relationship. Further, Moses specifies the plan and construction of the Tabernacle which is to be the seat of Yahweh's enthronement among His covenant people and the place where they are to present themselves before Him in worship.

From this perspective it can be observed that a more complete development of the book is structured around:

- Israel's deliverance from Egypt as a redeemed people separated to Yahweh (chapters 1-18);

- the constituting of Israel as a redeemed people to be a nation separated to Yahweh by covenant-relationship (chapters 19-24); and

- the enthronement of Yahweh as Israel's God-King dwelling in the Tabernacle among His redeemed and separated covenant people (chapters 25-40).

Synthesis of the text as a unified and coherent whole

The analyses discussed above have been used, implicitly and explicitly, to obtain an understanding of Exodus as a unified and coherent whole. This understanding is expressed here in the form the statement of its message, its synthetic structure, and the synthesis of the text which follows from that message and structure.

Development and statement of the message

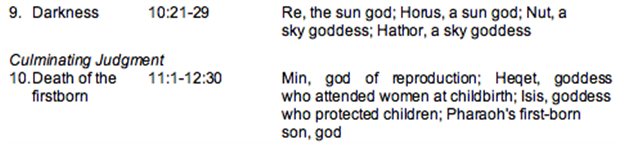

The Book of Exodus fits logically and theologically between the Books of Genesis and Leviticus. The Book of Genesis provides the historical context and basis for Israel's Exodus from Egypt, while the Book of Leviticus completes the Sinai covenant stipulations introduced in the Book of Exodus, particularly with respect to the form and function of the Levitical system of worship that was to be carried out in the Tabernacle, and with respect to a more complete definition of the holiness to which Israel was called. The Book of Exodus recounts the story of God's work in separating Israel from bondage in Egypt and of His redeeming them to bring them into covenant-relationship with Himself. This act of God irrupts (to break or burst into) in history as Yahweh takes action to fulfill His promises to Abraham.

The covenant-relationship, defined by the terms of the covenant treaty, is primarily a national relationship involving redemption which is both personal and national. The national dimension is not dependent upon individual appropriation, while the personal dimension is, of necessity, dependent upon such appropriation through faith in God's revelation of the Passover which takes on a more definitive meaning in the Book of Leviticus where the idea of atonement from sin is presented in terms of substitutionary sacrifice and blood used to effect atonement that bring spiritual meaning to the original Passover. By necessity, Yahweh's covenant-relationship with Israel demands Israel's redemption from sin, as well as from Egypt, in order that the holy God might dwell, or tabernacle, among His covenant people.

The Book of Exodus reveals Yahweh who constitutes a people separated to Himself by redemption, by covenant treaty, and by His own enthronement in the midst of their camp as King. Further, the book reveals Yahweh administering His purpose through Moses according to His word of promise to Abraham, and then according to His word of Law introduced to Israel through Moses at Sinai. In this sense the Book of Exodus is transitional with respect to the administration of God as it records the transition from promise to law. While God's word of promise to Abraham is ever and always the basis for God's working in and through Israel, His word of law becomes the immediate basis for blessing or cursing a particular generation as they respond to Him in obedience or disobedience to His law. It is not surprising that there is an element of obedience involved in receiving the blessings promised to Abraham, for God has declared that He chose Abraham in order that Abraham may command his children and his household after him to keep the way of Yahweh by doing righteousness and justice so that He, Yahweh, may fulfill all that He promised to Abraham (Gen 18:19). While the fulfillment of God's word of promise to Abraham stands completely upon God's unilateral commitment to it, a response of faith, demonstrated in obedience to Yahweh, is required for the realization of the promised blessings. It is important to recognize that it is necessary for Israel to respond to God’s word of Promise to Abraham with faith and that faith is measured in obedience to His commands.

The message of the Book of Exodus may be determined on the basis of the previous considerations discussed up to this point. The analysis of the text of Exodus suggests that a possible subject for this book is the constituting of Israel as a nation separated to Yahweh. When viewed from this perspective, the text of Exodus may be understood as making the following theological judgment/evaluation about this subject:

This understanding of Exodus leads to the following synthetic structure and synthesis of its text as a unified and coherent whole.

Synthetic structure of the text

The synthetic structure of Exodus is presented first in broad form and then in detail.

Broad synthetic structure

I. The deliverance of Israel from Egyptian bondage as a redeemed people separated to Yahweh (chs. 1-18)

A. The separation of Israel from Egypt through Yahweh's revelation of Himself in character and in judgment against Egypt (chs. 1-11)

1. The afflictions of Israel under Egyptian bondage (ch. 1)

2. The preparation and call of Moses to administer Yahweh’s deliverance of Israel (chs. 2-4)

3. The separation of Israel from Egypt through Yahweh's great judgments (chs. 5-11)

B. The redemption of Israel from Egypt (chs. 12-18)

1. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian bondage by blood through the Passover (12:1-13:16)

2. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian domination by water through the Red Sea (13:17-15:21)

3. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian dependency through Yahweh's provisions and testing in the wilderness (15:22-18:27)

II. The constituting of Israel as a redeemed people to be a nation separated to Yahweh by covenant-relationship (chs. 19-24)

A. The proposal and acceptance of the covenant through the mediation of Moses (ch. 19)

B. The legal stipulations of the covenant (chs. 20-23)

C. The ratification of the covenant (ch. 24)

III. The enthronement of Yahweh in the Tabernacle as Israel's God-King dwelling (tabernacling) among His redeemed and separated covenant people (chs. 25-40)

A. Specifications for the Tabernacle and Aaronic Priesthood (chs. 25-31)

B. Israel's breaking of the covenant, and its renewal through the mediation of Moses (chs. 32-34)

1. The breaking of the covenant through Israel's sin of idolatry (chs. 32-33)

2. The renewal of the covenant through the mediation of Moses (ch. 34)

C. The construction and consecration of the Tabernacle and the Aaronic priesthood (35:1-40:33)

D. Yahweh's enthronement in the Tabernacle as Israel's God and King dwelling (tabernacling) in the midst of His covenant people (40:34-38)

Detailed synthetic structure

I. The deliverance of Israel from Egyptian bondage as a redeemed people separated to Yahweh (1:1-18:27)

A. The separation of Israel from Egypt through Yahweh's revelation of Himself in character and in judgment against Egypt (1:1-11:10)

1. The afflictions of Israel under Egyptian bondage (1:2-22)

a. The cause of the afflictions: The great multiplication of the sons of Israel (1:1-7)

b. The nature of the afflictions: Forced hard labor which made their lives bitter (1:8-14)

c. The added degree of affliction: Pharaoh's command to the midwives to slay all newborn males (1:15-22)

2. The preparation and call of Moses to administer Yahweh’s deliverance of Israel (2:1-4:31)

a. The preparation of Israel's deliverer (2:1-22)

(1) Moses' birth and early childhood (2:1-10)

(2) Moses' failed attempt to effect deliverance for two of his brethren (2:11-15)

(3) Moses' resettlement in Midian (2:16-22)

b. The preparation of Israel for deliverance: Israel's cry for help (2:23-25)

c. The separation of Moses to Yahweh to deliver Israel from Egyptian bondage (3:1-4:31)

(1) Yahweh's call of Moses to deliver Israel from Egypt (3:1-10)

(a) Yahweh's revelation of Himself to Moses (3:1-6)

(b) Yahweh's revelation of His plan of deliverance to Moses (3:7-10)

(2) Moses' objections to Yahweh's call (3:11-4:17)

(a) Moses' first objection: "Who am I to go to Pharaoh?" (3:11-12)

(b) Moses' second objection: "What if they should ask what Your name is?" (3:13-22)

(c) Moses' third objection: "What if they will not believe me?" (4:1-9)

(d) Moses fourth objection: "I do not speak with eloquence." (4:10-17)

(3) Moses' submission to Yahweh's call (4:18-26)

(a) Moses' return to Egypt in response to Yahweh's call (4:18-23)

(b) Moses' circumcision of his sons in response to Yahweh's anger (4:24-26)

(4) Israel's acceptance of Moses as their deliverer (4:27-31)

3. The separation of Israel from Egypt through Yahweh's great judgments (5:1-11:10)

a. Moses' confronting of Pharaoh with the command of Yahweh to let Israel go (5:1-6:9)

(1) Moses' presenting of Yahweh's command to Pharaoh (5:1)

(2) Pharaoh's rejection of Yahweh's command (5:2-19)

(a) Pharaoh's refusal to let Israel go (5:2-3)

(b) Pharaoh's increase of Israel's affliction (5:4-19)

(3) Israel's rejection of Moses (5:20-21)

(4) Moses' questioning of Yahweh's plan of deliverance (5:22-23)

(5) Yahweh's affirmation of His intentions to deliver Israel (6:1-8)

(6) Moses' unsuccessful attempt to reassure the sons of Israel (6:9)

b. Moses' confronting of Pharaoh with a sign to effect Israel's deliverance (6:10-7:13)

(1) Yahweh's charge to Moses and Aaron to bring Israel out of Egypt (6:10-13)

(2) The genealogy of Moses and Aaron identifying them as the ones Yahweh charged with the task of bringing Israel out of Egypt (6:14-27)

(3) Yahweh's revelation of his intention to harden Pharaoh's heart and effect judgment upon Egypt (6:28-7:7)

(4) Moses' confronting Pharaoh with a sign (7:8-13)

(a) Yahweh's instructions to Moses to confront Pharaoh with a sign (7:8-9)

(b) The duplication of the sign by the Egyptian magicians (7:10-12)

(c) Pharaoh's hardening of his heart (7:13)

c. Moses' confronting of Pharaoh with Yahweh's devastating plagues of judgment upon Egypt to effect Israel's deliverance (7:14-11:10)

(1) The first plague: The Nile and all of Egypt's surface water turned to blood (7:14-25)

(2) The second plague: Egypt overrun with frogs (8: 1-15)

(3) The third plague: Egypt overtaken by gnats (8: 16-19)

(4) The fourth plague: Egypt laid waste by swarms of insects (8:20-32)

(5) The fifth plague: deadly pestilence upon Egyptian livestock (9:1-7)

(6) The sixth plague: painful boils on man and beasts throughout Egypt (9:8-12)

(7) The seventh plague: destructive hailstorms on all the land of Egypt (9:13-35)

(8) The eighth plague: devastating locusts devouring the land of Egypt (10:1-20)

(9) The ninth plague: absolute darkness over the land of Egypt (10:21-29)

(10) The tenth plague: announcement of the death of the first-born of Egypt (11:1-10)

B. The redemption of Israel from Egypt (12:1-18:27)

1. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian bondage by blood through the Passover (12:1-13:16)

a. The redemption of Israel through the redeeming of the first-born by blood: The institution of the Passover (12:1-28)

(1) Instructions for the Passover (12:1-13)

(a) Instructions concerning the Passover Lamb (12:1-6)

(b) Instructions concerning the application of the blood of the lamb (12:7)

(c) Instructions concerning the eating of the lamb (12:8-11)

(d) The effectiveness of the blood in redeeming the first-born from Yahweh's judgment directed against them (12:12-13)

(2) Instructions for the Unleavened Bread (12:14-20)

(3) Observance of the Passover and its institution as an ordinance to be celebrated every year (12: 21-28)

b. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian bondage as a result of obedience to the Passover (12:29-51)

(1) Yahweh's striking of all the first-born of Egypt with death (12:29-30)

(2) Pharaoh's submission to Yahweh's command to let Israel go (12:32-34)

(3) The fulfillment of Yahweh's promise to Abraham (12:35-42)

(a) Israel's plundering of the Egyptians (12:35-36)

(b) Israel's coming out of Egypt after 430 years of sojourning in the land (12:37-41)

(4) Additional instructions for observing the Passover (12:42-49)

(a) Observance of the Passover by all the sons of Israel as a commemoration of the night Yahweh brought Israel out of Egypt (12:42)

(b) Instructions for the celebration of the Passover by the true Israelite and by the foreigner living in the Land (12:43-49)

(5) The obedience of Israel in observing the Passover and its result–deliverance from the land of Egypt (12:50-51)

c. Institution of the ordinance for the consecration of the first-born to Yahweh with provision for redeeming the first-born son (13:1-16)

(1) The command to sanctify the first-born to Yahweh (13:1-2)

(2) The command to observe the Feast of Unleavened Bread in the Promised Land (13:3-10)

(3) The command to consecrate the life of the first-born to Yahweh with redemption of the first-born son permitted through the substitution of the life of an animal (13:11-16)

2. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian domination by water through the Red Sea (13:17-15:21)

a. Yahweh's strategic leading of Israel (13:17-14:4)

(1) Yahweh's leading of Israel through the wilderness to the Red Sea (13:17-22)

(2) Yahweh's leading of Israel to draw Pharaoh and his army to follow in pursuit (14:1-4)

(3) The pursuit of Pharaoh and his army (14:5-9)

b. Israel's redemption by water through the Red Sea (14:10-15:21)

(1) Yahweh's deliverance of Israel through the water of the Red Sea (14:10-22)

(a) Israel's fear of Egypt and lack of faith in Yahweh (14:10-14)

(b) Israel's safe crossing through the parted waters of the Red Sea (14:15-22)

(2) Yahweh's destruction of Pharaoh's army by the collapsing waters of the Red Sea (14:23-31)

(3) Israel's song of deliverance (15:1-21)

3. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian dependency through Yahweh's provisions and testing in the wilderness (15:22-18:27)

a. Yahweh's provision of sweet water (15:22-27)

(1) Israel's grumbling about bitter water (15:22-24)

(2) The miraculous provision of sweet water (15:25-27)

b. Yahweh's provision of manna and quail (16:1-36)

(1) Israel's grumbling about their lack of food (16: 1-3)

(2) The miraculous provision of food (16:4-21)

(3) The institution of the Sabbath (16:22-30)

(4) Yahweh's commands that a jar of manna kept as a memorial (16:31-36)

c. Yahweh's provision of water (17:1-7)

(1) Israel's grumbling about their lack of water (17: 1-4)

(2) The miraculous provision of water (17:5-7)

d. Yahweh's provision of victory over the Amalekites (17:8-16)

(1) Amaleck threatens Israel's security (17:8-10)

(2) The provision of victory (17:11-13)

(3) The memorial book (17:14-16)

e. Yahweh's provision of national leadership (18:1-27)

(1) The visit from Jethro (18:1-12)

(2) Jethro's counsel to Moses (18:13-23)

(3) Moses' choosing of leaders to judge under him (18:24-27)

II. The constituting of Israel as a redeemed people to be a nation separated to Yahweh by covenant-relationship (19:1-24:18)

A. The proposal and acceptance of the covenant through the mediation of Moses (19:1-25)

1. Yahweh's proposal of the covenant (19:1-6)

2. Israel's acceptance of the covenant(19:7-9)

3. Yahweh's appearance before all Israel (19:10-25)

a. The consecration of the people in preparation for Yahweh's appearing (19:10-15)

b. Yahweh's appearance on Mount Sinai (19:16-25)

B. The legal stipulations of the covenant (20:1-23:33)

1. The Ten Commandments of the covenant (20:1-17)

a. Prologue (20:1-2)

b. Commandments pertaining to man's relationship with God (20:3-11)

(1) First commandment: Prohibition against idolatry (20:3-6)

(2) Second commandment: Prohibition against misuse of God's name (20:7)

(3) Third commandment: Command to keep the Sabbath holy (20:8-11)

c. Commandments pertaining to man's relationship with man (20:12-17)

(1) Fourth commandment: Command to honor parents (20:12)

(2) Fifth commandment: Prohibition against murder (20:13)

(3) Sixth commandment: Prohibition against adultery (20:14)

(4) Seventh commandment: Prohibition against stealing (20:15)

(5) Eighth commandment: Prohibition against giving false testimony (20:16)

(6) Ninth commandment: Prohibition against coveting a neighbor's possessions (20:17a)

(7) Tenth commandment: Prohibition against coveting a neighbor's wife or servants (20:17b)

2. Stipulations for approaching Yahweh (20:18-26)

a. The fear of the people in reaction to their approaching Yahweh (20:18-21)

b. Yahweh's provision for an acceptable way of approaching Him (20:22-26)

(1) Prohibition of idolatry (20:22-23)

(2) Proper form of worship (20:24-26)

3. The ordinances of the covenant (21:1-23:33)

a. Laws concerning slaves (21:1-11)

b. Laws concerning personal injury (21:12-36)

c. Laws concerning theft (22:1-4)

d. Laws concerning property damage (22:5-6)

e. Laws concerning dishonesty (22:7-15)

f. Laws concerning immorality (16-17)

g. Laws concerning societal and religious obligations (22:18-23:9)

h. Laws concerning the Sabbath and national feasts (23:10-19)

i. Laws concerning taking possession of the Promised Land (23:20-33)

C. The ratification of the covenant through the mediation of Moses (24:1-18)

1. Israel's ratification of the covenant (24:1-8)

a. Israel's pledge to obey all the ordinances of the covenant as enumerated by Moses (24:1-3)

b. Israel's offering of sacrifices to Yahweh through the mediation of Moses (24:4-6)

c. Israel's pledge to obey all the ordinances of the covenant as read by Moses from the book of the covenant (24:7)

d. The binding of Israel's pledge through the sprinkling of the blood of the covenant (24:8)

2. Yahweh's acceptance of Israel's commitment to the covenant (24:9-18)

a. Yahweh's acceptance manifested through His appearing on Mount Sinai to Moses and the elders of Israel (24:9-11)

b. Yahweh's acceptance manifested through His giving Moses a copy of the covenant law written on stone tablets (24:12-18)

III. The enthronement of Yahweh in the Tabernacle as Israel's God-King dwelling (Tabernacling) among His redeemed and separated covenant people (25:1-40:38)

A. Specifications for the Tabernacle and Aaronic Priesthood (25:1-31:18)

1. The collection of construction materials through freewill offerings (25:1-9)

2. The specifications for the Tabernacle's furniture (25:10-40)

a. Specification of the ark and the mercy seat (25:10-22)

b. Specification of the table and its utensils (25:23-30)

c. Specification of the lampstand (25:31-40)

3. The specifications for the Tabernacle's overall structure (26:1-37)

a. Specification of the curtains (26:1-14)

b. Specification of the boards (26:15-30)

c. Specification of the veils (26:31-37)

4. The specifications for the bronze altar, court of the Tabernacle, and the oil for the lamps (27:1-21)

a. Specification of the bronze alter (27:1-8)

b. Specification of the court (27:9-19)

c. Specification of the oil (27:20-21)

5. The specifications for the Aaronic priesthood (28:1-29:46)

a. The appointment of Aaron and his sons to minister as priests, and the specifications for their garments (28:1-43)

(1) The appointment of Aaron and his sons to minister as priests before Yahweh (28:1-5)

(2) Instructions for making the priestly garments (28:6-43)

b. The ordination and consecration service for the installation of the Aaronic priesthood (29:1-46)

6. The specification for the altar of incense and the laver (30:1-38)

a. Specification of the altar of incense (30:1-10)

b. The atonement money (30:11-16)

c. Specification of the laver (30:17-21)

d. Specification of the anointing oil (30:22-33)

e. Specification of the incense (30:34-38)

7. The appointment of craftsman to oversee the building of the Tabernacle (31:1-11)

8. The specification of the Sabbath observance: The sign of the covenant (31:12-18)

B. Israel's breaking of the covenant and its renewal through the mediation of Moses (32:1-34:35)

1. The breaking of the covenant through Israel's sin of idolatry (32:1-10)

a. Israel's sin of idolatry through worshiping the golden calf (32:1-6)

b. Yahweh's burning anger against Israel (32:7-10)

2. The renewal of the covenant through the mediation of Moses (32:11-34:35)

a. The mediation of Moses to appease the anger of Yahweh (32:11-33)

(1) Moses' intercession before Yahweh entreating Him to remember His covenant with Abraham (32: 11-14)

(2) Moses' anger toward the people (32:15-29)

(3) Moses' intercession before Yahweh for mercy (32:30-35)

(a) Moses' acknowledgment of Israel's great sin (32:30-31)

(b) Moses' plea for forgiveness (32:32)

(c) Yahweh's judgment upon the people– punishment instead of destruction (32:33-35)

b. The mediation of Moses to turn Yahweh away from withdrawing His presence from Israel (33:1-23)

(1) The repentance of the people in response to Yahweh's pledge not to dwell in their midst (33:1-11)

(2) Moses' intercession before Yahweh reminding Him that Israel is distinguished from the other nations because of His presence with His people (33:12-16)

(3) Yahweh's agreement to go with Israel and to reveal His glory to Moses (33:17-23)

c. The renewal of the covenant (34:1-35)

(1) The renewal of the covenant by Yahweh (34:1-28)

(a) Yahweh's revelation of Himself to Moses (34:1-9)

(b) Yahweh's pledge to renew the covenant (34:10)

(c) Yahweh's commandment to destroy the Canaanites and their instruments of idolatry (34:11-17)

(d) Yahweh's commandment to observe the feasts, the dedication of the first-born, and the Sabbath, as instituted by Yahweh (34:18-26)

(e) Moses' writing down of the words of the covenant in accordance with Yahweh's command (34:27-28)

(2) The renewal of the covenant by Israel (34:29-35)

C. The building of the Tabernacle (35:1-40:33)

1. The preparations for building the Tabernacle (35:1-36:7)

a. Moses' exhortation to the people to give freewill offerings to Yahweh for constructing the Tabernacle (35:1-19)

b. The outpouring of offerings by the people (35:20-29)

c. The appointment of the craftsman having the responsibility to construct the Tabernacle (35:30 -36:7)

2. The fabrication of the Tabernacle items (36:8-39:31)

a. The fabrication of the curtains (36:8-19)

b. The fabrication of the boards (36:20-34)

c. The fabrication of the veil (36:35-38)

d. The fabrication of the ark with its mercy seat (37:1-9)

e. The fabrication of the table and its utensils (37:10-16)

f. The fabrication of the lampstand and its utensils (37:17-24)

g. The fabrication of the altar of incense, the anointing oil, and the incense (37:25-29)

h. The fabrication of the altar of burnt offering and its utensils (38:1-7)

i. The fabrication of the laver (38:8)

j. The fabrication of the court (38:9-20)

k. Summary of the material used to fabrication the components of the Tabernacle (38:21-31)

l. The fabrication of the priestly garments (39:1-31)

3. The construction and consecration of the Tabernacle and the Aaronic priesthood (39:32-40:33)

a. Moses' inspection all the Tabernacle items (39:32-41)

b. The erection and consecration of the Tabernacle, and the installation and consecration of the Aaronic priesthood (40:1-33)

D. Yahweh's enthronement in the Tabernacle as Israel's God and King dwelling (tabernacling) in the midst of His covenant people (40:34-38)

Synthesis of the text

Based on the message statement and synthetic structure developed above a synthesis of the text of Exodus may be constructed as follows:

I. The deliverance of Israel from bondage in Egypt irrupts as Yahweh redeems the sons of Israel and separates them to Himself in fulfillment of His promise to Abraham. (1:1-18:27)

A. The separation of Israel from Egypt irrupts as Yahweh calls Moses to serve Him and reveals Himself in character and in judgment against Egypt. (1:1-11:10)

1. The multiplication of the sons of Israel into a great number brings about severe affliction as the Egyptians, fearing the potential for the Israelites to turn against them, make their lives bitter through hard forced labor. (1:1-22)

2. The separation of Moses to Yahweh as Israel's deliverer irrupts as Yahweh remembers His covenant with Abraham and reveals His intention to deliver Israel from bondage in Egypt through Moses. (2:1-4:31)

a. Moses' preparation as Israel's deliverer begins with his protection in birth and early childhood, continues with his failed attempt to effect deliverance for two of his brethren, and culminates in his flight to, and resettlement in Midian as a lowly shepherd. (2:1-22)

b. Yahweh remembers His covenant with Abraham as Israel's cries for help cause Him to take notice of their bondage in Egypt. (2:23-25)

c. The separation of Moses to Yahweh, in spite of Moses' strong objections, irrupts as Yahweh reveals Himself to Moses and reveals His plan to send him back to Egypt to deliver His people from bondage. (3:1-4:31)

3. The separation of Israel from Egypt irrupts as Yahweh, in response to Pharaoh's defiance of His demand to let Israel go, reveals Himself in judgment against Egypt demonstrating His sovereignty over men, nations, nature and idols. (5:1-11:10)

a. Moses' first attempt to obtain Israel's release ends in apparent failure as Pharaoh defiantly rejects Yahweh's demand and imposes harsher demands on Israel's labor causing both Moses and the sons of Israel to question Yahweh's intent, but Yahweh reassures His chosen deliverer that He will deliver Israel from their bondage and redeem them with great judgments and bring them into the land He promised to give Abraham, all in fulfillment of the covenant He made with Abraham. (5:1-6:9)

b. Moses' second attempt to obtain Israel's release manifests Pharaoh's hardened heart, as the sign Moses performed is duplicated by Pharaoh's magicians leading him not to listen to Moses. (6:10-7:13)

c. The hardening of Pharaoh’s heart toward acknowledging the God of Israel's authority over him, moves Yahweh to execute judgment upon Egypt and its gods through a series of plagues, culminating in a judgment of death against the first-born of Egypt, which destroys Egypt and breaks the resolve of Pharaoh's hardened heart not to let Israel go. (7:14-11:10)

B. Yahweh’s deliverance of Israel through the blood of the Passover lamb, the waters of the Red Sea, and His provisions for them and testing of them in the wilderness, separates them from Egyptian bondage to Himself as He leads them to Mount Sinai. (12:1-18:27)

1. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian bondage irrupts as Yahweh executes judgment on the first-born of every man and animal in the land of the Egyptians, while the first-born of Israel is redeemed from death through the blood of a lamb slain in obedience to Yahweh's command to observe the Passover. (12:1-13:16)

a. The institution of the Passover reveals Yahweh's plan to effect Israel's redemption from Egyptian bondage by redeeming Israel's first-born through the application of the blood of an unblemished lamb to be sacrificed and then eaten in haste in anticipation of being suddenly thrust out of Egypt in response to His judgment of death against all the first-born of Egypt. (12:1-28)

b. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian bondage occurs, exactly 430 years after the sons of Israel went into Egypt, as Yahweh strikes all the first-born of Egypt with death, while the first-born of Israel are delivered through the obedient application of the blood of the Passover lamb. (12:29-51)

c. The ordinance for the consecration of the first-born to Yahweh, with provision for redeeming the first-born son, is instituted as a means for Israel to remember from one generation to another that Yahweh redeemed Israel from slavery in Egypt with a mighty hand as He killed every first-born in the land of Egypt except the first-born of Israel who were redeemed through the blood of the Passover lamb. (13:1-16)

2. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian domination irrupts as Yahweh separates Israel from the pursuing Egyptian army through the waters of the Red Sea which serve as a means of deliverance for Israel but death for the Egyptians. (13:17-15:21)

a. Yahweh's strategic leading of Israel through the wilderness to the shores of the Red Sea leaves them vulnerable to Pharaoh's pursuing army. (13:17-14:9)

b. Israel's fear and grumbling turns to great joy as Yahweh redeems His people from Egyptian domination through the waters of the Red Sea by parting the waters for Israel's safe passage, and then by allowing the waters to return to their normal position thereby drowning the pursuing Egyptian army. (14:10-15:21)

3. The redemption of Israel from Egyptian dependency irrupts as Yahweh's testing of Israel in the wilderness demonstrates, in spite of their grumbling, His power to provide food, water, protection, and leadership, while His introducing them to the concept of the Sabbath day further separates them from their lifestyle in Egypt and prepares them for living a life separated to Him in covenant-relationship. (15:22-18:27)

II. The constituting of Israel as a redeemed people to be a nation separated to Yahweh irrupts as Yahweh proposes a bilateral (Suzerainty-Vassal) covenant-relationship and Israel accepts by pledging themselves to obey all that He commands and by ratifying that pledge through the blood of the covenant. (19:1-24:18)

A. The constituting of Israel as a kingdom of priests and a holy nation separated to Yahweh and living under His rule irrupts as Yahweh, from atop Mount Sinai and through the mediation of Moses, proposes a covenant-relationship to His redeemed people which they accept. (19:1-25)

B. The covenant law binding Israel to Yahweh specifies foundational commandments and legal stipulations which define their covenant responsibilities to Yahweh and to each other. (20:1-23:33)

1. The covenant law binding Israel to Yahweh specifies ten commandments which define the fundamental nature of Israel’s relationship with Yahweh and with each other as they live within the community of the redeemed. (20:1-26)

2. The covenant law binding Israel to Yahweh specifies legal stipulations of the covenant which regulate the social and religious behavior of the redeemed people. (21:1-23:33)

C. The formal acceptance of the covenant by Israel binds the redeemed people in covenant-relationship to Yahweh and Him to them in a suzerainty-vassal relationship. (24:1-18)

1. The ratification of the covenant is formalized as the people twice pledge themselves to obeying all the words of Yahweh written in the book of the covenant, and as Moses sprinkles them with the blood of the covenant. (24:1-8)

2. Yahweh's acceptance of Israel's ratification of the covenant is manifested through His appearing on Mount Sinai to Moses and the elders of Israel, and through His giving Moses a copy of the covenant law written on stone tablets. (24:9-18)

III. The enthronement of Yahweh as Israel's God and King (Suzerain) irrupts as Yahweh, in spite of Israel's rebellion and breaking of the covenant through idolatry, comes to dwell (tabernacle) among His people and the glory of His presence fills the Tabernacle. (25:1-40:38)

A. The specification of the plans for the Tabernacle provides Israel with the details of its material, of the form and function of its component parts, of the Aaronic priesthood which is to minister before Yahweh in it, the designation of those who will have responsibility for building it, and the details for observing the Sabbath. (25:1-31:18)

B. The constitution of Israel as a redeemed people separated to Yahweh in covenant-relationship is threatened as the breaking of the covenant erupts with the people of Israel worshiping a golden calf, but Moses' mediation and the repentance of the people lead to a renewal of the covenant and restoration of the relationship. (32:1-34:35)

1. The breaking of the covenant erupts through Israel's sin of idolatry, as their profane worship of a golden calf causes Yahweh to burn with anger and seek to destroy them. (32:1-10)

2. The persistent mediation of Moses on behalf of the people of Israel appeases the anger of Yahweh, while the repentance of the people leads them to renew the covenant under Moses' leadership. (32:11-34:35)

a. The mediation of Moses appeases Yahweh's anger as Moses entreats Him to remember His covenant with Abraham and to have mercy on His people, yet the people would be punished for their sin. (32:11-35)

b. The mediation of Moses turns Yahweh away from withdrawing His presence from Israel as the people repent and Moses reminds Yahweh that Israel is distinguished from the other nations because of His presence with His people. (33:1-23)

c. The renewal of the covenant comes about through Moses' mediation as Yahweh pledges Himself to the covenant, and as the sons of Israel renew their pledge to obey all the stipulations of the covenant. (34:1-35)

(1) The renewal of the covenant results through Moses' mediation as Yahweh first reveals Himself to Moses and then pledges Himself to the covenant, but not without warning Israel to make sure that they destroy the Canaanites and all their instruments of idolatry, lest they fall into the abominations of the people He is driving out before them, and to be sure to observe the festivals He instituted. (34:1-28)

(2) The renewal of the covenant by Israel takes place as Moses, after returning from speaking with Yahweh, commands the sons of Israel to do everything that Yahweh had spoken about to him on Mount Sinai. (34:29-35)

C. The construction of the Tabernacle in exact accordance with Yahweh’s specifications, and its consecration and the consecration of the Aaronic Priesthood, completes the dwelling place for Yahweh to tabernacle among His people. (35:1-40:33)

D. Yahweh's enthronement in the Tabernacle as Israel's God and King dwelling (tabernacling) among His redeemed and separated people irrupts as the cloud of His presence covers the Tent of Meeting and His glory fills the Tabernacle. (40:34-38)

1The Book of Exodus begins with the irruption of God's action on the part of Israel [irruption is God coming in from outside of history into history to work, to act, to perform miracles]. But this changes by the end of the book. By the time that the book reaches its conclusion God has settled into history by dwelling in the Tabernacle. Now He is no longer working from outside of history, rather He is working in history as He relates to His covenant people, and indeed the rest of the world, from inside the Tabernacle. This image of God working inside history remains the same until the Book of Ezekiel when Israel goes into captivity and the glory of Yahweh departs the Temple and returns to heaven. This situation remains until the coming of Christ, the Seed of the woman, when God again irrupts into history.

2Some gods and goddesses had more than one function or area of responsibility. Also, in ancient Egyptian religion many of the gods and goddesses who were worshiped in one city or location and/or at one period of time were believed to have assimilated the gods and goddesses of other areas and time periods. Their religion was thus often complex and at times even contradictory.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines

3. Analysis And Synthesis Of Leviticus

Related MediaThe analysis and synthesis approach to biblical studies applied here to Leviticus is a methodology developed by the author (DeCanio, 2007) in conjunction with his doctoral studies at the University of South Africa. An abbreviated version of this work entitled, Biblical Hermeneutics and a Methodology for Studying the Bible, will be posted as an article on bible.org.

The bibliography for this study of Leviticus is presented at the end of the article, Introduction to the Pentateuch.

Analysis Of The Context

The aim of this analysis is to consider aspects of the context in which the book of Leviticus was written, such as its authorship, recipients, time period of historical events and composition, and its biblical context, which may be useful in understanding the book as a whole.

Authorship

The Book of Leviticus, like all the other books of the Pentateuch, is anonymous, having no explicit indication of authorship. While the text makes it abundantly clear that the Law was given to Israel through Moses (see, for example, the many statements “Then Yahweh spoke to Moses, saying, 4:1;5:14; 6:1, 8; etc.), nowhere does it ever state that Moses wrote down what he heard. In view of Scriptural support for Mosaic authorship for whole of the Pentateuch (see the Introduction to the Pentateuch for a discussion of this issue), and in view of the intimately close association of Leviticus with the Book of Exodus where it explicitly states that Moses wrote down all that Yahweh said (Exod 24:4), it is reasonable to assume Mosaic authorship of Leviticus.

Recipients

The Book of Leviticus is specifically addressed to the sons of Israel (see, for example, 1:2; 4:2; 7:23; and 11:2), and Aaron and his descendants (see, for example, 6:9; and 8:2). In view of the fact that the covenant Israel entered into was not just for the Exodus generation, but for all succeeding generations, Moses’ wider audience must necessarily include later generations of Israelites as well.

Time Period Of Historical Events And Composition

Date Of Events

There are no chronological indicators in the Book of Leviticus and so the date of the events in this book must be determined from chronological data given in other books of the Pentateuch. The Book of Leviticus begins with “Then Yahweh called to Moses and spoke to him from within the tent of meeting, saying, . . . “(1:1). This statement shows strong continuity with the Book of Exodus with then connecting the instructions of Leviticus with the closing of Exodus (see, for example, Exod 40:34-38). From this perspective, it is known from Exodus 40:17 that the Tabernacle was erected on the first day of the first month of the second year from the Exodus. Further, it is known from the Book of Numbers that Yahweh spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai from in the Tent of Meeting on the first day of the second month of the second year (Num 1:1). This would date the giving of the instructions recorded in Leviticus in the first month of the second year from the Exodus, or in the Spring of the year 1445 B.C. (assuming a date of 1446 B.C. for the Exodus as argued for in the Introduction to the Pentateuch). Thus it would seem, that the giving of the Law recorded in the Book Leviticus occurred over a one month period of time.

Date Of Composition

Assuming Mosaic authorship, the Book of Leviticus would have to have been written sometime between the beginning of the second year from the Exodus and the end of the fortieth year when Moses died (Deut 34:5-7)—sometime between 1445 and 1406 B.C. More likely, Moses would have immediately written down the instructions from Yahweh as he had received them, even as he did for the instructions recorded in the Book of Exodus (Exod 24:4). Assuming this to be the case, Leviticus could have been written as early as 1445 B.C.

Biblical Context

The biblical context consists of three components; the historical element, the socio–cultural element, and the theological element. Before discussing these elements, it is important to consider the relationship with the Book of Exodus.

Relationship With The Book Of Exodus

The close relationship between the books of Exodus and Leviticus is seen in terms of their historical and theological relationships.

Historical Relationship

The Book of Leviticus is, from a historical perspective, a sequel to, or, more likely, a continuation of, the Book of Exodus (Lindsey 1985:163). This evident in several ways. First, the Levitical sacrificial system was a divine revelation to Israel through Moses as a part of the covenant obligation given at Sinai. In this sense it completes the revelation given in Exodus which details the Tabernacle in terms of its component parts and its construction. Leviticus completes this revelation by informing Israel the function of the Tabernacle in their covenant-relationship with Yahweh. Further, the Book of Leviticus opens with Yahweh calling to Moses from within the now completed Tabernacle (1:1). Thus the laws of sacrifice, worship, and holiness contained in Leviticus follows the historical narrative concerning the construction of the Tabernacle (Exod 25-40), and the subsequent indwelling of Yahweh in the Tabernacle (Exod 40:34-35). A consideration of Exodus 40:2, 17, and Numbers 1:1 and 10:11 indicates that the events of the Book of Leviticus took place over a period of one month, during which time Israel remained at Sinai. Therefore, historically, chronologically, and, as next discussed, theologically, Leviticus correctly follows Exodus and precedes Numbers.

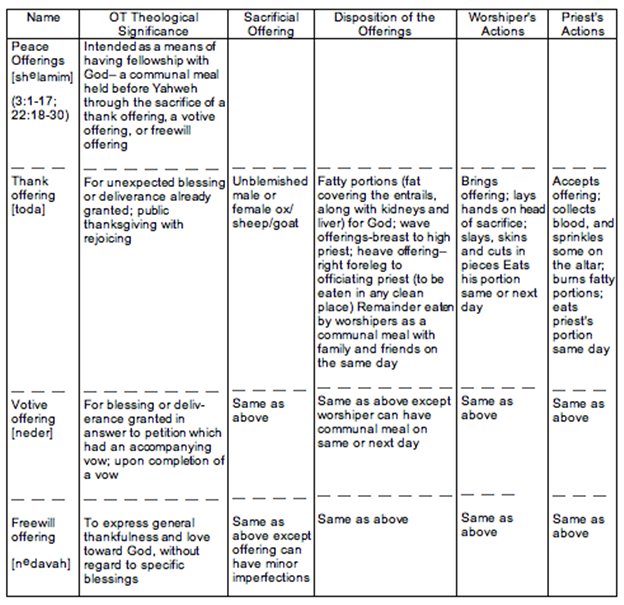

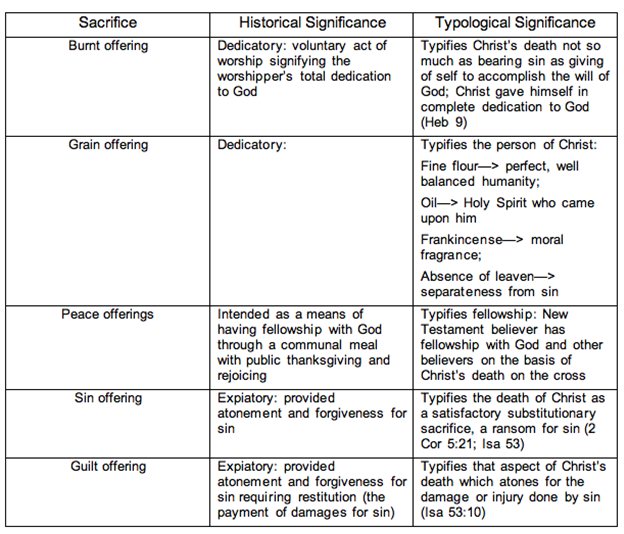

Theological Relationship

The Levitical sacrificial system was instituted by God for a people he had redeemed from Egypt at the time of the Passover and brought into covenant-relationship with himself at Sinai (Lindsey 1985:164). Thus to offer a sacrifice to Yahweh was not human effort seeking to obtain favor with a hostile God, but a response to Yahweh who had first given Himself to Israel in covenant-relationship. Rather the function of the Levitical sacrifices is to restore fellowship with Yahweh whenever sin or impurity, whether moral or ceremonial, disrupted this fellowship. The individual or the nation (whichever was the case) needed to renew covenant fellowship through sacrifice, the particular sacrifice depending on the exact circumstance of the disruption.

Further, while Israel was called to be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation to Yahweh (Exod 19:6), the people needed to be instructed on how to achieve this lofty goal. The Book of Leviticus informs Israel in practical terms what it means for them to be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation. Thus Leviticus provides the practical theology that is missing in the Book of Exodus. For all practical purposes there should be no division between the Books of Exodus and Leviticus; they form one book.

Historical Element

The Book of Exodus ends with the erection of the Tabernacle which was constructed according to the pattern God gave to Moses. The question that now needed to be addressed was, “How was Israel to use the Tabernacle?” The instructions given to Moses during the one month and 20 days between the setting up of the Tabernacle (Exod 40:17) and the departure of Israel from Sinai (Num 10:11) and recorded in the Book of Leviticus answers that question. Thus, both historically and theologically, the Book of Leviticus completes the Book of Exodus and forms a historical and theological bridge to the Book of Numbers, and beyond that to the Book of Deuteronomy, for the historical and theological presuppositions found in the last two books of the Pentateuch are rooted in the Books of Exodus and Leviticus.

Historically, it is significant to note that at the beginning of the Book of Leviticus Moses is outside the Tabernacle (Lev 1:1), while at the beginning of the book of Numbers he is inside the Tabernacle (Num 1:1). It is important to note here that the “tent of meeting” referred to in Exodus 33:7-11 is not the Tabernacle which was constructed later. Further, only Moses was inside the tent, for the presence of Yahweh, localized in the pillar of cloud, would descend and stand at the entrance of the tent. The Book of Exodus ends with Yahweh on the inside of the Tabernacle/tent of meeting and Moses outside not able to enter because the glory of Yahweh filled the Tabernacle (Exod 40:35). The Book of Leviticus begins with Yahweh on the inside of the Tabernacle calling to Moses on the outside (Lev 1:1). One month later (see, for example, Exod 40:2, 17 and Num 10:11 for chronological data) Moses was on the inside speaking with Yahweh (Num 1:1). This is representative of the historical fact that there is progression in relationship as a result of the Law given in Leviticus.

Socio-Cultural Element