The Old Testament Historical Books (Joshua Through Esther): An Outline

Related MediaPreface

The Old Testament historical books (Joshua to Esther) represent the development of the people of Israel from their entrance to Canaan to their exile to Babylon. They are essential for understanding the history and faith of God’s people.

It has been my pleasure and delight to serve the Lord both as pastor and professor for over 60 years. Most of those years have been spent in the classroom. These outline notes are the product of that labor and, even though they are designed for everyone, some linguistic aspects are more usable by seminary graduates.

Most of my time at Capital Bible Seminary was invested in Hebrew grammar and exegesis. My years at Dallas were primarily in the Bible Exposition Department where I taught Historical Books for eight years.

We live in strange days. W. F. Albright, almost single handedly, in the middle of the last century, moved the Old Testament theological needle from radical liberal to moderately conservative. He believed there was an Abraham, that Moses was monotheistic, that there was an exodus, and that archaeology and Bible study went hand in hand. He had such towering scholarship that many became his followers, and few were his critics.

Now, however, that needle has swung back. The so-called minimalists believe in very little biblical history. There was virtually nothing in the David/Solomon era, and, of course, no patriarchal history, no exodus, and no conquering of the land.

These notes represent an attempt to interact with the critical issues and still maintain a conservative view of Scripture. My prayer is that they will be helpful to those who use them

Suggestions and corrections are always welcome.

Homer Heater, Jr.

Capital Bible Seminary

For a print version of this resource, it may be purchased here on Amazon.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Old Testament, Pastors, Teaching the Bible

Old Testament Wisdom And Poetry (Job Through Song Of Solomon): An Outline

Related MediaPreface

For eight years, I taught students historical books, prophets, and wisdom literature at Dallas Theological Seminary, and at Capital Bible Seminary for 30 years. It gives one great joy to see many of those students entering the ministry and serving the Lord.

Wisdom (Proverbs) and Psalms are favorite parts of the Bible to believers. Job is known primarily through chapters 1-2 and 42. The rest of Job is usually ignored, and Ecclesiastes is especially avoided. It is hoped that these notes will bring enlightenment on these books and, perhaps, lead the reader into a fuller understanding of their intent and content.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Pastors, Teaching the Bible

1. Proverbs

Related MediaIntroduction To Wisdom

Wisdom literature has two types of literary genre that are very significant and quite different from the material found in the Historical books: Hebrew poetry and Hebrew wisdom literature. We will give a cursory introduction now so that we can appreciate the material we are studying.

1. Hebrew Poetry. See discussion under Psalms.

2. Hebrew Wisdom Literature

LaSor, et al. point out two main types of wisdom writing: proverbial wisdom—short, pithy sayings which state rules for personal happiness and welfare or condense the wisdom of experience and make acute observations about life; and contemplative or speculative wisdom—monologues, dialogues, or essays which delve into basic problems of human existence such as the meaning of life and the problem of suffering. They hasten to add that “speculative” and “contemplative” should not be interpreted in a philosophical sense because the Hebrews always thought in historical, concrete terms.1

Most of Proverbs fit the first category, and Job and Ecclesiastes (Qoheleth) fit the second. Some of each will be found in the Psalms, and other parts of Scripture. Some of Jesus’ teaching will fall into the category of wisdom literature as he uses proverbs, pithy sayings, monologues and essays to convey his teaching. See also the discussion of Psalm 49 as a wisdom Psalm.

I am putting Proverbs first in the notes because they are in the first category. We know from 1 Kings 4:29-31 as well as the extrabiblical literature, that wisdom was common in that world. Wisdom deals with what is “under the sun.” In other words, how do we conduct ourselves in this world. All wisdom teaching was concerned with right conduct, but Proverbs brings an element absent from non-biblical wisdom: “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom.” Generally speaking, wisdom teaches that A (right conduct) leads to B (God’s blessing), C (wicked conduct) leads to D (God’s judgment). John 9:1-3 is an example of how the disciples were still following this paradigm. Job and Qoheleth are attacking the absolute application of this formula. Of course, it generally works out according to the paradigm, but not always. Wise conduct is always right, but it does not always bring the looked-for blessing. Still, it is to be followed.2

Proverbs

I. Introductory data.

A. Contents. “Proverbs seems to contain at least eight separate collections, distinguishable by either an introductory subtitle or a striking change in literary style. Prov. 1:1‑6 is a general introduction or superscription, clarifying both the book’s purpose and its connection with Solomon, Israel’s master sage.”3

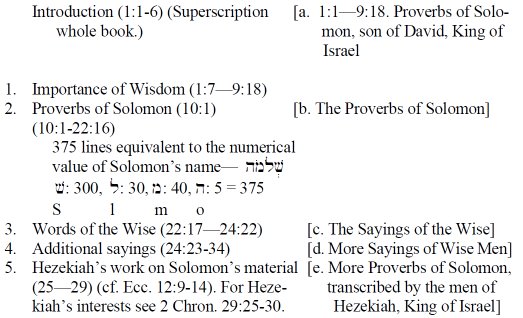

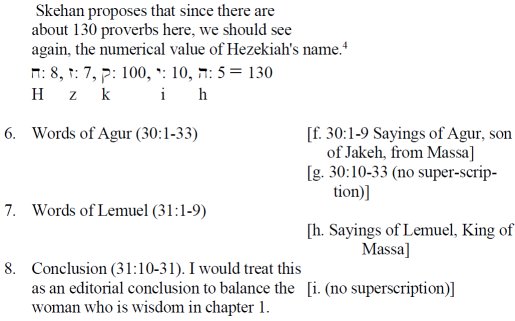

Contents—LaSor, eight separate collections, Crenshaw, James L. Old Testament Wisdom, an Introduction, Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1981, in brackets.

B. Authorship. There is more than one author to the proverbs. Solomon, as the principal and best-known author is listed in the heading, but there are others, some of whom are non-Israelite. Kidner is probably correct about the composition of the book: “As to its editing Proverbs gives us one statement (25:1), which shows that the book was still in the making at c. 700 BC, about 250 years after Solomon. It is a fair assumption, but no more, that chapters 30‑31 were added later as existing collections, and chapters 1‑9 placed as the introduction to the whole by the final editor.”4

C. “Limits of Wisdom. In seeking to interpret the various proverbs and apply them to life, one must bear in mind that they are generalizations. Though stated as absolutes—as their literary form requires—they are meant to be applied in specific situations and not indiscriminately. Knowing the right time to use a proverb was part of being wise: ‘A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in a setting of silver’ (25:11).”5 “Haste makes waste. “He who hesitates is lost.”

D. Proverbs tend to be stated in absolutes: A = B; that is, if one obeys God, one is blessed with health, long life, and prosperity. On the contrary, C = D; that is if one disobeys God, one is cursed with bad health, early death, and poverty. Job and Ecclesiastes are wisdom books written to wrestle with the exceptions. Job’s friends are determined to prove that in his case the prevailing idea of wisdom controls: C = D. Job, however, argues (rightly) that in his case A = D. He can only conclude that God is unjust. In the end, the question of “why” is not answered; God simply says, I am sovereign and can do what I wish. Man must trust God; that He will always do right. But even in Proverbs A does not equal B and C does not equal D. See Prov. 16:8, 16, 19, 32; 17:1.

E. The place of torah תּוֹרָה (law) in the book.

The word “law” occurs in the introduction (1:8—9:18) six times; in the proverbs of Solomon (10:1—22:16) one time; in Solomon’s proverbs copied out by Hezekiah’s men (25:1—29:27) four times; and in the section by Lemuel’s mother one time.

At no time is the phrase “the law of Moses” used, nor “God’s law,” nor any other phrase that would tie the teaching of Proverbs directly to the law. However, the phrases “my law,” “the law of your mother” (parallel to “instruction of your father” and “commandment of your father”) seem to have a subtle indication that behind the instruction of father, mother, teacher, lies the covenant law of God. This is particularly indicated in such phrases as “wreath to your head” and “ornaments about your neck,” (1:8,9); “bind them about your neck; write them upon the tablet of your heart,” (3:3, here it is kindness and truth) “bind them continually on your heart; tie them around your neck; when you walk about, etc.,” (6:21-22) “bind them on your fingers; write them on the tablet of your heart,” (7:3); which sound much like the Deuteronomic admonitions that eventually led to the practice of wearing phylacteries (Deut 6:1-9). The pertinent references are 1:8; 3:1; 4:2; 6:20,23; 7:2; 13:14; 28:4,7,9; 29:18; 31:26.

There is a cluster at the beginning and one at the end of the book. 13:14 could be mere teaching (vs. the law), but all the other references are set out on the backdrop of the Mosaic covenant (with the exception of 31:26 and even there it is the “law of kindness” torath ḥesed תּוֹרַת חֶסֶד). Consequently, at least in these two units where the clusters occur, it would be inappropriate to argue that the law is not subtly in the background.

F. At the same time, we must understand a distinction between the casuistic law of Moses and wisdom. The emphasis on the latter is the practical outworking of the “instruction of Yahweh” and, therefore, must be understood as the kind of conduct experience has taught is the right way to be “perfect” with God and man.6

G. Bad side of wisdom.7

1. Serpent who was subtle or crafty (Gen 3).

2. Jonadab and Amnon (2 Sam 13).

3. Wise woman of Tekoa (2 Sam 14) and the wise woman of Abel (2 Sam 20) seemed to use wisdom for questionable ends.

H. Jeremiah 18:18 seems to indicate a separate class of Wise Men. See also 25:1, Hezekiah's Men.

I. Categories:

1. Proverbs (mašal): basic similitude, likeness, or a powerful word (second meaning of this word is “to rule”).

2. Parables (meliṣah) seems to point in the directions of sayings which carry a sting hidden within their clever formulation and may by extension refer to admonitions and warnings.

3. Wise Sayings: general category and serves as headings.

4. Riddles: (ḥidoth) designates enigmatic sayings and perhaps even extensive reflections on the meaning of life and its inequities. (1 Kings 10:1-13 Solomon with Queen of Sheba).

5. Two allegorical texts stand out as worthy links with riddles (old age Ecc 12:1-8 and marital fidelity Prov 5:15-23)

6. Didactic narrative (Prov 7:6-23 Seductress leading the fool).8

J. The canonical book of Proverbs has been given a carefully worded introduction which functions to set the several collections into a common framework. This valuable section (Proverbs 1:2-7) uses many different words to characterize those who master the Solomonic proverbs: wisdom (חָכְמָה ḥokmah), instruction, (מוּסַר musar) understanding (בִּינָה binah), intelligence, discretion (הַשְׂכֵּל haśkil), righteousness ( צֶדֶקṣedek), justice (מִשְׁפָט mišpat), equity (מֵישָׁרִים mešarim), knowledge (דַּעַת da‘ath), prudence ( עָרְמָה ‘armah), learning (לֶקַח leqaḥ), and skill (מְזִמָה mezimah).9

K. Some structural observations.

1. Two invitations (1:8-33).

a. Sinners call (1:8-19).

b. Wisdom calls (1:20-33).

2. Right relationships (3:1-35).

a. With the Lord (3:1-12) “Lord,” “God,” and “He” appear 10 times in 1-35.

b. With Wisdom (3:13-26).

c. With your neighbor (3:27-35).

3. Contrasts (5:1-23).

a. Sin with an adulteress (5:1-14). Live righteously with your wife (5:15-23).

b. The adulteress (7:1-26). Lady wisdom (8:1-36).

c. Lady wisdom (9:1-6). Rival minds: wisdom (9:7-12//folly (9:13-18).

4. Numerology

a. Proverbs of Solomon (10:1-22:16) 375 lines = Solomon (300, 30, 40, 5).

b. Hezekiah's men (25—29) 130 lines = Hezekiah (8, 7, 100, 10, 5).

c. Total proverbs (1-31) c. 932 lines = David (14), Solomon (375), Israel (541) = 930.

5. Fear of the Lord

a. 9:10 end of first unit.

b. 15:33 Middle of book and of second unit (Massora = middle is 16:18)

c. 31:30 End of the book.

6. Acrostic (31:10-31).

L. Sources of Wisdom

1. Family or clan (father and mother as teachers and son, may be taken literally).

2. Court (perhaps “men of Hezekiah”)

3. School (perhaps, but definitely in Ben Sira).10

II. An Attempt to Develop Principles for Interpreting Proverbs.

A. We must understand dispensational truth.

This principle means that God revealed certain things in certain periods of time that had limited application (to that period). Failure to distinguish this basic hermeneutical principle will result in the error of Seventh Day Adventism. On the other hand, some truths are universal and will be valid in each of the dispensations. The problem is distinguishing these two types of revelation.

B. Old Testament teaching must be sifted through the grid of revelation given directly to the Church: Acts and the Epistles.

Each teaching of the OT must be compared with Church teaching to see whether it is applicable in the current dispensation. At least three types of statements would be applicable:

1. Reiterated statements.

These are statements that appear in the NT epistles in the same or similar form. “Thou shalt not bear false witness against your neighbor” Exod. 20:16. This statement appears in Eph. 4:25 as “Stop lying to one another.” The Christian knows that this is wrong, not because it appears in Exodus, but because it appears in Ephesians. The fact that it appears in both shows its universality and allows the Christian to emphasize it from both dispensational passages.

2. Quoted statements.

When the OT passage is quoted in the NT as an applicational truth, it should be considered applicational to the Church. “If your enemy hungers, feed him” Prov. 25:21 (cf. also Matt. 5:44). Paul quotes this proverb in Rom. 12:20.

3. Parallel statements.

This is similar to 1 above. It differs in that the parallels will be more general than “reiterated statements.” “That they [wise words] may keep you from the adulteress, from the foreigner who flatters with her lips” Prov. 8:5. This idea is found in 1 Thes. 4:3: “For this is the will of God even your sanctification that you abstain from fornication.”

4. Items that do not fall under these categories, i.e., neither commanded nor forbidden in the NT, should not be treated as commands. If they are consonant with NT teaching in general, they may be applied as principles. An example would be tithing which is taught in the Law and practiced before the law. However, since it is not taught in the NT, and Paul does not mention it in the passages where he talks about giving, it should not be considered binding teaching on the Church. Some may follow the practice, but they should not impose it on others.

C. Proverbs presents special problems for interpretation and application.

The very nature of wisdom literature is that it is the distillation of observation of human nature and is designed to provide general guidance for right living. It is indeed inspired literature, but its genre demands that we understand it to be a collection of general observations and principles of wise conduct. Take the statement: “Wealth brings many friends, but a poor man’s friend deserts him.” This is comparable to our proverb: “A friend in need is a friend indeed.” The proverb means that people with money tend to attract those who hope to receive benefits, but when wealth is gone, such people tend to disappear. It is not saying that wealth always brings friends, nor that poverty always causes friends to desert; it is saying that such behavior often occurs. Each proverb must be studied carefully in its context and under the discipline of NT revelation to determine whether and how the statement is to be applied in the church age.

D. The following proverbs are a paradigm for interpretation. Ask how each one fits into the above scheme of things and see whether it is a general observation or a universal truth (text from the NASB).

|

10:4 |

Poor is he who works with a negligent hand, |

|

Exceptions: |

Not all diligent workers become rich. |

|

NT parallels: |

For even when we were with you, we used to give you this order: if anyone will not work, neither let him eat (2 Thes. 3:10). |

|

10:5 |

He who gathers in summer is a son who acts wisely, but he who sleeps in harvest is a son who acts shamefully. |

|

Exceptions: |

No. This is a statement that is general and always true. It makes no specific promise. |

|

NT parallels: |

Perhaps: “Whatever you do, do your work heartily as for the Lord rather than for men” Col. 3:23. |

|

12:11 |

He who tills his land will have plenty of bread. But he who pursues vain things lacks sense. |

|

Exceptions: |

We all know believers and unbelievers alike who work hard but do not have plenty of bread. This is still a general observation of what is usually true. |

|

12:24 |

The hand of the diligent will rule, But the slack hand will be put to forced labor. |

|

Exceptions: |

Do all diligent people wind up in places of leadership? |

|

12:27 |

A slothful man does not roast his prey, But the precious possession of a man is diligence. |

|

13:4 |

The soul of the sluggard craves and gets nothing, But the soul of the diligent is made fat. |

|

14:23 |

In all labor there is profit, But mere talk leads only to poverty. |

|

Exceptions: |

Not all labor brings profit, although it usually does. |

|

All general observations |

|

|

15:19 |

The way of the sluggard is as a hedge of thorns, But the path of the upright is a highway. |

|

18:9 |

He also who is slack in his work, Is brother to him who destroys. |

|

19:15 |

Laziness casts into deep sleep, and an idle man will suffer hunger. |

|

19:24 |

The sluggard buries his hand in the dish and will not even bring it back to his mouth. |

|

20:4 |

The sluggard does not plow after the autumn, so he begs during the harvest and has nothing. |

|

20:13 |

Do not love sleep, lest you become poor; Open your eyes, and you will be satisfied with food. |

|

21:25 |

The desire of the sluggard puts him to death, For his hands refuse to work; |

|

21:26 |

All day long he is craving, While the righteous gives and does not hold back. |

|

22:13 |

The sluggard says, “There is a lion outside; I shall be slain in the streets!” |

|

26:13 |

The sluggard says, “There is a lion in the road! A lion is in the open square!” |

|

26:14 |

As the door turns on its hinges, so does the sluggard on his bed. |

|

26:15 |

The sluggard buries his hand in the dish; He is weary of bringing it to his mouth again. |

|

26:16 |

The sluggard is wiser in his own eyes, than seven men who can give a discreet answer. |

|

28:19 |

He who tills his land will have plenty of food, but he who follows empty pursuits will have poverty in plenty. |

III. Outline notes on Proverbs.

A. Introduction (1:1‑7).

The introduction is written to establish at the outset the primary place of wisdom as “godliness in work clothes.” Verse 7 can be taken as the overriding theme in the book: Even though Proverbs is the practical outworking of the religious life, it is a covenant book that never strays from the foundation of Yahweh’s covenant with His people. This verse contains six words that will recur again and again in the book: fear, Yahweh, knowledge, fools, wisdom, and instruction.

B. Importance of Wisdom (1:8‑9:18).

In 2 Kings we meet Solomon’s son, and we are not impressed with his wisdom. As a matter of fact, he followed the foolish advice of his younger contemporaries and lost most of the kingdom. This might lead us to question whether this section represents Solomon addressing his son, and the answer is “probably not.” This unit is more likely the product of the “sages” who compiled the book of Proverbs. The father in this unit is the teacher and the son is the pupil.

The teacher addresses the pupil as son.11 His purpose is to draw a contrast between the results of seeking and finding wisdom and those of pursuing a life of folly.12

1. Two invitations and two refusals (1:8‑33).

a. The invitation from sinners (1:8‑19).

The enticement from these wicked people is to become involved in violent stealing (mafia style). Becoming rich is the lure, but the method is to lie in wait like brigands along the highway. In actuality these people bring death to themselves through their illicit actions: the wealth gained by stealth actually deprives its possessor of life itself. In the contemporary atmosphere this is a very apropos warning.

b. The invitation of wisdom (1:20‑33).

Stark contrast is wisdom, personified as a lady, who stands in the street and beckons to any who will hear to come to the place in life where they can “live securely and be at ease from the dread of evil.” She addresses the “naive ones” (pethim פְּתִים). This word as a verb is translated “entice” at 1:10. This person is an easily enticed person. “Scoffers” (leṣim לֵצִים) appear some seventeen times in Proverbs. Kidner says: “His presence there [coupled with the fool] makes it finally clear that mental attitude, not mental capacity, classifies the man. He shares with his fellows their strong dislike of correction . . ., and it is this, not any lack of intelligence, that blocks any move he makes towards wisdom.”13 The “fools” (kesilim כְּסִילִים) hate knowledge. These strong terms are used to describe deliberate rejection of God’s truth. They are not to imply, as Kidner says, lack of intellectual capacity, but lack of moral strength. Their way is correctable, but they must choose to follow wisdom not folly.

2. The benefits of seeking wisdom (22 lines as in the alphabet) (2:1‑22).

The sage uses a series of protases (“if” clauses) to lay down the conditions for blessing (2:1‑3). The result of the first series is in 2:5: “Then you will discern the fear of the Lord, and discover the knowledge of God.” (Note the equation of fear [yir’ath יִרְאַת] and knowledge [da’th דַּעַת]. Note further the covenant name of Yahweh.) The apodoses (“then” clauses) come in 2:5‑11. The practical outworking of such acquisition is given in 2:12‑22: “To deliver you from the way of evil;” “To deliver you from the strange woman.”

3. The Father (teacher) encourages his son to have the right relationship with the Lord, wisdom and his neighbor (3:1‑35).

This triad is in the list in the same sequence of their appropriation: God must be first. There is a great emphasis on knowing God. Practical wisdom is very important, but it never supersedes God. “Lean not to your own understanding,” is a warning from a sage with much understanding. Knowing God brings wisdom, the marvelous ability used by God in creating the universe. Finally, when one has come to know God, and through that knowledge, wisdom, he is in a position to act with propriety toward his neighbor. This order is essential in the Christian ministry. You will only be able to deal with people properly when you are in proper vertical relationship with God. This in turn gives you wisdom to deal with people.

4. The Father (teacher) instructs the son to seek the traditional value of wisdom (4:1‑9).

As the sage was taught as a youngster by his father and mother, so he instructs his pupil to accept proper teaching. The effect on his life will be as a garland on the head. His life will be graceful and gracious.

5. The father (teacher) instructs the son to choose the way of righteous-ness and avoid the way of wickedness (4:10‑19).

Habitual conduct cuts both ways. The one who lives a habitually wicked life will become entrenched in such conduct. Conversely, the one who makes it a practice to do right will find that becoming his character. The student is urged to pursue the right way.

6. The father instructs his son to discipline himself (4:20‑27).

Good words are important. What one reads and listens to will have an effect on him. This proper attitude, of course, requires discipline, but the impact is well worth it.

7. The father instructs his son against harlotry (5:1‑23).

Two unchanging truths are presented in this chapter: the avoidance of the prostitute and the pursuit of a proper relationship with one’s wife. This theme appears several times in Proverbs. Adultery is devastating (5:22‑23), and no one is above the possibility. It is God who watches all and sees all. This chapter should be read often by all those in Christian work.

8. The father instructs the son about three follies and seven abominations to the Lord (6:1‑19).

“Co‑signing” is a dangerous process. However, like all the proverbs, there may very well be times when it is the proper thing to do. Because it is dangerous, the student is advised to avoid it with all diligence (6:1‑5).

Laziness is the second folly. It is a thief of productivity and happiness. Avoid it in the Lord’s work as well. Since there is often little or no supervision, the full‑time Christian worker must be careful not to be lazy (6:6‑11).

The third folly is worthlessness. This is the word we encountered in earlier books (beliyya‘al בְּלִיַּעַל): “without value.” What a pronounce-ment to be made over a person! This individual is slick and devious; to be avoided at all costs (6:12‑15).

The seven abominations to Yahweh are: haughty eyes (pride), lying tongue (deceit), hands that shed innocent blood (violence), heart that devises wicked plans (deviousness), feet that run rapidly to evil (immoral conduct), a false witness (perversion of truth), and one who spreads strife (divisive spirit) (6:16‑19).

9. The father instructs the son against adultery (6:20‑35).

The sage returns to this serious problem of adultery. Walking in the truth of the Scripture will avoid this devastating entanglement with another person’s spouse.

10. The father gives a description of two women—the harlot and wisdom (7:1—8:36).

The sage seems to blend the idea of literal adultery with that of spiritual unfaithfulness. The positive is pursuit of wisdom, the negative is the harlot (or lack of wisdom). A detailed description is given of the seduction of a young man (7:1‑27).

Having dealt with the negative facet of purity, the sage now turns to the positive: wisdom. The student is to listen to the call of the one who brings sound living and conduct. The closing part of this praise of wisdom (8:22‑36) personifies wisdom almost the same way as does John the Logos (John 1:1‑12).14

11. The father speaks of two rival feasts and two rival minds (9:1‑18).

The introduction to Proverbs is ending, and the statement that the fear of Yahweh is the beginning of wisdom is reiterated (9:10). Wisdom has attractively prepared a feast to call the simple to the place of understanding (9:1‑6).

But some minds are so set against spiritual truth that they obstinately refuse to be instructed. The wise man becomes wiser (the one talent is given to the man with ten), but the foolish man becomes more foolish. Yet there is hope: if the fool will turn to God, he can become wise (9:7‑12).

The woman of folly (literally the prostitute, but figuratively the rejection of wisdom) calls people to her feast also, but the end of it is the depths of Sheol (9:13-18).

C. Proverbs of Solomon (10:1—22:16).

The biblical claims for Solomonic activity in the realm of wisdom are found in 1 Kings 4:29ff; Prov. 1:1; 10:1; 25:1. There are approximately 375 proverbs in this section.15 They are primarily based on practical observations from everyday life. They are very practical, and stress the profits or rewards of right living.

Scott says: “‘The Wise Sayings of Solomon,’ covers the collection of independent and mostly miscellaneous two-line aphorisms and precepts which comprise Part II. A second collection, also connected with the name of Solomon, is found in chaps. xxv-xxix (Part IV); it is broadly similar to the first collection but is more secular and less didactic in tone.”16

Rather than go through the section verse by verse, we will arrange the proverbs topically, following Scott’s layout.17

Read through the following proverbs, synthesize them and summarize the teaching in each group.

1. A son and his parents.

A wise son makes a father glad, But a foolish son is a grief to his mother (10:1).

He who gathers in summer is a son who acts wisely, But he who sleeps in harvest is a son who acts shamefully (10:5).

13:1, 24; 15:20; 17:21, 25; 19:26; 20:20.

2. Character and its consequences.

What the wicked fears will come upon him, And the desire of the righteous will be granted (10:24).

The hope of the righteous is gladness, But the expectation of the wicked perishes (10:28).

11:27, 30; 12:3, 7, 12, 20, 21, 28; 13:6, 9, 10; 14:19, 22, 30, 32; 16:20; 17:19, 20; 18:3; 19:16; 20:7; 21:5, 16, 17, 18, 21; 22:5.

3. Providential rewards and punishments.

The Lord will not allow the righteous to hunger, But He will thrust aside the craving of the wicked (10:3).

The way of the Lord is a stronghold to the upright, But ruin to the workers of iniquity (10:29).

11:18, 21, 23, 25, 31; 12:2; 13:21, 22; 14:9, 11, 14; 15:6, 10, 25; 19:29; 20:30; 22:4.

4. Poverty and wealth.

Ill-gotten gains do not profit, But righteousness delivers from death (10:2).

Poor is he who works with a negligent hand, But the hand of the diligent makes rich (10:4).

10:15, 22; 11:4, 24, 28; 13:8, 11; 14:20; 18:11, 23; 19:1, 4, 7, 22; 20:21; 21:6, 20; 22:27.

5. Good and evil men.

Blessings are on the head of the righteous, But the mouth of the wicked conceals violence (10:6).

The memory of the righteous is blessed, But the name of the wicked will rot (10:7).

10:9, 10, 11, 16, 21, 25, 27, 30; 11:5, 6, 8, 19, 30; 12:5, 26; 16:27, 28, 29, 30; 17:4; 21:8, 12, 26, 29; 22:10.

6. Wise men and fools.

The wise of heart will receive commands, But a babbling fool will be thrown down (10:8).

On the lips of the discerning, wisdom is found, But a rod is for the back of him who lacks understanding (10:13).

10:14, 23; 12:1, 8, 15, 23; 13:15, 16; 14:6, 7, 8, 15, 16, 18, 24, 33; 15:7, 14, 21; 17:10, 12, 24.

7. Slander.

He who conceals hatred has lying lips, And he who spreads slander is a fool (10:18).

The words of a whisperer are like dainty morsels, And they go down into the innermost parts of the body (18:8).

19:5, 9, 28.

8. The self-disciplined life.

He is on the path of life who heeds instruction, But he who forsakes reproof goes astray (10:17).

The one who despises the word will be in debt to it, But the one who fears the commandment will be rewarded (13:13).

13:14, 18; 16:32.

9. Foolish talk, temperate speech, and wise silence.

When there are many words, transgression is unavoidable, But he who restrains his lips is wise (10:19).

The tongue of the righteous is as choice silver, The heart of the wicked is worth little (10:20).

10:31, 32; 11:12, 13; 12:6, 13, 14, 18; 13:2, 3; 14:3, 23; 15:1, 2, 4, 23, 28; 16:21, 23, 24; 17:27, 28; 18:4, 6, 7, 13, 20, 21; 20:19; 21:23; 22:11.

10. Work and idleness.

Like vinegar to the teeth and smoke to the eyes, So is the lazy one to those who send him (10:26).

He who tills his land will have plenty of bread, But he who pursues vain things lacks sense (12:11).

12:24, 27; 13:4; 14:4, 23; 15:19; 16:26; 18:9; 19:15, 24; 20:4, 13; 21:25; 22:13.

11. Women and marriage.

A gracious woman attains honor, And violent men attain (only?) riches (11:16).

As a ring of gold in a swine’s snout, So is a beautiful woman who lacks discretion (11:22).

12:4; 18:22; 19:14; 21:9, 19.

12. Family relationships.

He who troubles his own house will inherit wind, And the foolish will be servant to the wise-hearted (11:29).

Grandchildren are the crown of old men, And the glory of sons is their fathers (17:6).

18:19; 19:13.

13. Civic morality.

When it goes well with the righteous, the city rejoices, And when the wicked perish, there is glad shouting (11:10).

By the blessing of the upright a city is exalted, But by the mouth of the wicked it is torn down (11:11).

11:14, 26; 14:34; 21:15.

14. Rash promises.

He who is surety for a stranger will surely suffer for it, But he who hates going surety is safe (11:15).

A man lacking in sense pledges, And becomes surety in the presence of his neighbor (17:18).

20:16, 25.

15. Truth and falsehood.

He who speaks truth tells what is right, But a false witness, deceit (12:17).

Truthful lips will be established forever, But a lying tongue is only for a moment (12:19).

12:22; 13:5; 14:5, 25; 17:7.

16. Honesty and dishonesty.

The righteous has enough to satisfy his appetite, But the stomach of the wicked is in want (13:25).

He who profits illicitly troubles his own house, But he who hates bribes will live (15:27).

16:11; 20:10, 14, 23.

17. Morality and religion.

He who walks in his uprightness fears the Lord, But he who is crooked in his ways despises Him (14:2).

The fear of the Lord is a fountain of life, That one may avoid the snares of death (14:27).

21:3, 4, 27.

18. A king and his people.

In a multitude of people is a king’s glory, But in the dearth of people is a prince’s ruin (14:28).

The king’s favor is toward a servant who acts wisely, But his anger is toward him who acts shamefully (14:35).

16:10, 12, 13, 14, 15; 19:12; 20:2, 8, 9, 26, 28; 21:1.

19. Material and moral values.

Better is a little with righteousness Than great income with injustice (16:8).

How much better it is to get wisdom than gold! And to get understanding is to be chosen above silver (16:16).

16:19; 20:15; 22:1.

20. The administration of justice.

Abundant food is in the fallow ground of the poor, But it is swept away by injustice (13:23).

He who justifies the wicked, and he who condemns the righteous, Both of them alike are an abomination to the Lord (17:15).

17:23, 26; 18:5, 17, 18; 21:28.

21. The discipline of education.

A fool rejects his father’s discipline, But he who regards reproof is prudent (15:5).

He whose ear listens to the life-giving reproof Will dwell among the wise (15:31).

15:32; 17:16; 18:15; 19:8, 18, 20, 27; 22:6, 15.

22. God’s oversight of man’s life.

The plans of the heart belong to man, But the answer of the tongue is from the Lord (16:1).

All the ways of a man are clean in his own sight, But the Lord weighs the motives (16:2).

16:3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 33; 17:3; 19:21; 20:12, 24, 27; 21:2, 30, 31; 22:12.

23. Behavior acceptable to God.

The perverse in heart are an abomination to the Lord, But the blameless in their walk are His delight (11:20).

The sacrifice of the wicked is an abomination to the Lord, But the prayer of the upright is His delight (15:8).

15:9, 26, 29.

24. The nemesis of folly and wrongdoing.

A rebellious man seeks only evil, So a cruel messenger will be sent against him (17:11).

He who returns evil for good, Evil will not depart from his house (17:13).

19:19; 20:17; 21:7; 22:8, 16.

25. Happiness.

A joyful heart makes a cheerful face, But when the heart is sad, the spirit is broken (15:13).

All the days of the afflicted are bad, But a cheerful heart has a continual feast (15:15).

15:16, 17, 30; 17:22.

26. Cruelty and compassion.

A righteous man has regard for the life of his beast, But the compassion of the wicked is cruel (12:10).

He who despises his neighbor sins, But happy is he who is gracious to the poor (14:21).

14:31; 17:5; 19:17; 21:10, 13; 22:9.

27. The path of life.

There is a way which seems right to a man, But its end is the way of death (14:12).

The path of life leads upward for the wise, That he may keep away from Sheol below (15:24).

16:12, 17.

28. Various virtues and vices.

Hatred stirs up strife, But love covers all transgressions (10:12).

A false balance is an abomination to the Lord, But a just weight is His delight (11:1).

11:2, 3, 9, 17; 12:9, 16, 25; 13:7; 14:17, 29; 15:12, 22, 33; 16:18; 17:9, 11, 17; 18:1, 12, 24; 19:2, 6, 11; 20:1, 6, 11, 22; 21:24.

29. The power of religious faith.

In the fear of the Lord there is strong confidence, And his children will have refuge (14:26).

The fear of the Lord is a fountain of life, That one may avoid the snares of death (14:27).

18:10; 19:23.

30. Sickness and grief.

The heart knows its own bitterness, And a stranger does not share its joy (14:10).

Even in laughter the heart may be in pain, And the end of joy may be grief (14:13).

18:14.

31. Quarrels.

A hot-tempered man stirs up strife, But the slow to anger pacifies contention (15:18).

Better is a dry morsel and quietness with it Than a house full of feasting with strife (17:1).

17:14; 20:3.

32. Plans and expectations.

When a wicked man dies, his expectation will perish, And the hope of strong men perishes (11:7).

Hope deferred makes the heart sick, But desire fulfilled is a tree of life (13:12).

13:19.

33. Wisdom and folly.

The wise woman builds her house, But the foolish tears it down with her own hands (14:1).

Understanding is a fountain of life to him who has it, But the discipline of fools is folly (16:22).

20:5, 18; 21:22.

34. Divine omniscience.

The eyes of the Lord are in every place, Watching the evil and the good (15:3).

Sheol and Abaddon lie open before the Lord, How much more the hearts of men! (15:11).

35. Old age.

A gray head is a crown of glory; It is found in the way of righteousness (16:31).

The glory of young men is their strength, And the honor of old men is their gray hair (20:29).

36. Gifts and bribes.

A bribe is a charm in the sight of its owner; Wherever he turns, he prospers (17:8).

A man’s gift makes room for him, And brings him before great men (18:16).

15:27; 21:14.

37. Messengers and servants.

A wicked messenger falls into adversity, But a faithful envoy brings healing (13:17).

A servant who acts wisely will rule over a son who acts shamefully, And will share in the inheritance among brothers (17:2).

38. Good and bad company.

He who walks with wise men will be wise, But the companion of fools will suffer harm (13:20).

The mouth of an adulteress is a deep pit; He who is cursed of the Lord will fall into it (22:14).

D. Words of the Wise (See NIV) (22:17—24:22).

The phrase “words of the wise” (divre ḥakamim דִּבְרֵי חֲכָמִים) was probably originally a heading that later became part of the first line. The authorship is unknown, but these proverbs may have been copied out by Hezekiah’s scribes as in 25:1. They are usually longer than those of the previous section. The phrase “thirty [sayings]” (22:20) may have some connection with Egyptian wisdom (as did the last two sections). Kidner says, “Egyptian jewels, as at the Exodus, have been reset to their advan-tage and put to finer use.”18

1. Introduction (22:17‑21).

a. The student is admonished to listen to wise words (22:17).

b. The results of listening will be pleasant (22:18).

c. The teacher speaks of his curriculum (22:19‑21).

2. There are thirty precepts in what follows: (22:22—24:22).

a. The student is admonished not to take advantage of helpless people (22:22‑23).

b. The student is warned against associating with hot-tempered people (22:24‑25).

c. He is warned against co‑signing for people (22:26‑27).

d. He is warned against moving boundary markers (22:28).

e. He is admonished to become skillful in his work (22:29).

f. He is taught to use discretion when eating at a ruler’s table (23:1‑3).

g. He is warned against the struggle to be rich (23:4‑5).

h. He is warned against becoming entangled with a selfish man (23:6‑8).

i. He is warned against wasting his wisdom on fools (23:9). “Do not cast your pearls before swine.”

j. He is warned again about moving boundary markers (23:10‑12). Note the word Redeemer (Heb.: goel גֹּאֵל); the same designation as in Job 19:25 with a similar function.

k. He is instructed to discipline children (23:13‑14).

l. He is told that his wisdom will make his teacher happy (23:15‑16).

m. He is to put his confidence in the Lord and not be envious, for God promises him a future (23:17‑18).

n. He is to avoid incontinence in drinking and eating (23:19‑21).

o. He is to listen to sound advice and thus “buy truth and get wisdom” (23:22‑23).

p. He is encouraged to be wise and to listen to his teacher (23:24‑25).

q. He is warned to avoid the harlot (23:26‑28).

r. He is warned against drunkenness (23:29‑35). (This is the descript-tion of an alcoholic).

s. He is warned against envy of evil men (24:1‑2).

t. Wise living brings good results (24:3‑4).

u. Wisdom brings victory (24:5‑6).

v. Wisdom is not for fools (24:7).

w. Trouble makers are fools (24:8‑9).

x. The wise person is not to withdraw in a time of distress (24:10).

y. He is to deliver those being taken to death (24:11-12). (He cannot make an excuse that he did not know.)

z. The teacher compares wisdom to honey (24:13‑14).

aa. The wicked is warned not to cheat the righteous (24:15‑16).

bb. The student is admonished not to rejoice at the fall of his enemy (24:17‑18).

cc. The student is told not to be envious of the wicked (24:19‑20).

dd. The student is admonished to respect existing institutions (24:21‑22).

E. Additional Sayings of the Wise (24:23‑34).

These are the product of an anonymous group of wise men.

1. Fairness and justice are a blessing (24:23‑26).

2. Diligence requires work to be done that produces money before work that produces relaxation (24:27).

3. The student is warned about being a false witness (24:28‑29).

4. He is warned against laziness (24:30‑34).

F. Proverbs of Solomon Copied by Hezekiah’s men (25:1‑29:27).

Hezekiah was interested in the temple, singing, Psalms, and other liturgy (2 Chron. 29:25‑30). This is a brief glimpse into some of the process of collecting wisdom sayings and transmitting them.

The following topical arrangement comes from Scott, Proverbs, p. 171.

1. The discipline of education.

Like an earring of gold and an ornament of fine gold Is a wise reprover to a listening ear (25:12).

Iron sharpens iron, So one man sharpens another (27:17).

29:1, 15, 17, 19, 21.

2. Reward and retribution.

He who digs a pit will fall into it, And he who rolls a stone, it will come back on him (26:27).

He who tends the fig tree will eat its fruit; And he who cares for his master will be honored (27:18).

28:10, 17, 18, 19, 20, 25.

3. Good and evil men.

The wicked flee when no one is pursuing, But the righteous are bold as a lion (28:1).

Those who forsake the law praise the wicked, But those who keep the law strive with them (28:4).

28:5, 12, 16, 28; 29:6, 7, 10, 27.

4. The fool. 26:1-12.

Like snow in summer and like rain in harvest, So honor is not fitting for a fool (26:1).

A whip is for the horse, a bridle for the donkey, And a rod for the back of fools (26:3).

26:4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11; 27:3, 22; 29:9.

5. Wisdom and folly.

Do you see a man wise in his own eyes? There is more hope for a fool than for him (26:12).

He who trusts in his own heart is a fool, But he who walks wisely will be delivered (28:26).

6. Gossip and slander.

Do not go out hastily to argue your case; Otherwise, what will you do in the end, When your neighbor puts you to shame? (25:8).

Argue your case with your neighbor, And do not reveal the secret of another (25:9).

25:10, 11, 18, 23; 26:22.

7. Other vices and follies.

Like one who takes off a garment on a cold day, or like vinegar on soda, Is he who sings songs to a troubled heart (25:20).

Like a trampled spring and a polluted well Is a righteous man who gives way before the wicked (25:26).

25:27, 28; 26:13, 14, 15, 16; 27:4, 8, 13, 20; 28:22, 23; 29:22, 23.

8. Various virtues.

Like the cold of snow in the time of harvest Is a faithful messenger to those who send him, For he refreshes the soul of his masters (25:13).

Like clouds and wind without rain Is a man who boasts of his gifts falsely (25:14).

25:15, 16, 17, 19; 27:9, 10, 12; 28:27.

9. Morality and religion.

He who turns away his ear from listening to the law, Even his prayer is an abomination (28:9).

He who conceals his transgressions will not prosper, But he who confesses and forsakes them will find compassion (28:13).

28:14; 29:25, 26.

10. Character.

As in water face reflects face, So the heart of man reflects man (27:19).

The crucible is for silver and the furnace for gold, And a man is tested by the praise accorded him (27:21).

11. Rich and poor.

A sated man loathes honey, But to a famished man any bitter thing is sweet (27:7).

A poor man who oppresses the lowly Is like a driving rain which leaves no food (28:3).

28:6, 8, 11; 29:13.

12. The royal court.

It is the glory of God to conceal a matter, But the glory of kings is to search out a matter (25:2).

As the heavens for height and the earth for depth, So the heart of kings is unsearchable (25:3).

25:4, 5, 6, 7.

13. Rulers.

By the transgression of a land many are its princes, But by a man of understanding and knowledge, so it endures (28:2).

Like a roaring lion and a rushing bear Is a wicked ruler over a poor people (28:15).

29:2, 4, 8, 12, 14, 16, 18.

14. Foolish speech.

A lying tongue hates those it crushes, And a flattering mouth works ruin (26:28).

Do not boast about tomorrow, For you do not know what a day may bring forth (27:1).

27:2; 29:11, 20.

15. Father and son.

Be wise, my son, and make my heart glad, That I may reply to him who reproaches me (27:11).

He who keeps the law is a discerning son, But he who is a companion of gluttons humiliates his father (28:7).

28:24; 29:3.

16. Enemies.

If your enemy is hungry, give him food to eat; And if he is thirsty, give him water to drink (25:21).

For you will heap burning coals on his head, And the Lord will reward you (25:22).

27:5, 6.

17. Women and marriage.

It is better to live in a corner of the roof Than in a house shared with a contentious woman (25:24).

A constant dripping on a day of steady rain And a contentious woman are alike (27:15).

27:16.

18. Good news.

Like cold water to a weary soul, So is good news from a distant land (25:25).

19. Curses.

Like a sparrow in its flitting, like a swallow in its flying, So a curse without cause does not alight (26:2).

He who is a partner with a thief hates his own life; He hears the oath but tells nothing (29:24).

20. Quarrels.

Like one who takes a dog by the ears Is he who passes by and meddles with strife not belonging to him (26:17).

For lack of wood the fire goes out, And where there is no whisperer, contention quiets down (26:20).

26:21.

21. Hypocrisy.

Like an earthen vessel overlaid with silver dross Are burning lips and a wicked heart (26:23).

He who hates disguises it with his lips, But he lays up deceit in his heart (26:24).

26:25, 26; 29:5.

22. The practical joker.

Like a madman who throws Firebrands, arrows and death (26:18).

So is the man who deceives his neighbor, And says, “Was I not joking?” (26:19).

27:14.

23. The diligent farmer.

Know well the condition of your flocks, And pay attention to your herds (27:23).

For riches are not forever, Nor does a crown endure to all generations (27:24).

27:25, 26, 27.

G. Words of Agur (30:1‑33).

The word “oracle” is the Hebrew word Masa (מַשָּׂא) but may refer to a tribe rather than an oracle. The tribe would be a descendant of Ishmael (Gen 25:14). The use of this material indicates the international character of wisdom literature, which, under divine inspiration, was brought into the canon.

The two names in v. 2 should probably be repointed and divided into phrases rather than proper names: “I have wearied myself, Oh God, I have wearied myself and am consumed.”19

This material is different from the preceding both in content and style.

1. The greatness of God is extolled (30:1‑4).

The section sounds like Job.

“What is His name or His son’s name?” should be related to 8:22‑31 where wisdom is personified in the creation process. We indicated there that the mediating “word” was a subtle reference to the coming “Word.” The “son” of this section should be related to the wisdom of chapter 8. Delitzsch: “God the creator and His son the mediator.”

2. The word of God is extolled (30:5‑6).

3. The prayer of the King is not to have too much or too little (30:7‑9).

4. A general statement is made about slandering slaves (30:10).

5. There are four kinds of evil men: those who curse parents, profess to be pure when filthy and are arrogant (30:11‑14).

6. A series of truths are set forth in the ascending number style (30:15‑31).

a. Things never satisfied: Sheol, barren womb, arid earth, and fire. (An additional statement about mocking parents) (30:15‑17).

b. Amazing things: eagle, snake, ship, and man with a maid (30:18‑20).

c. Obnoxious things: slave/king, fool/sated, unloved woman/marries, maidservant/supplanting her mistress (30:21‑23).

d. Small but capable things: ants (strong), badgers (in rock houses), locusts (form ranks), lizard (lives in kings’ houses) (30:24‑31).

e. He then gives a conclusion about self-control (30:32‑33).

H. Words of King Lemuel (31:1‑9).

King Lemuel is unknown apart from the passage. The Rabbis identified him with Solomon, but most would argue that he and Agur the Massite are probably from the same place (see Gen. 25:14; 1 Chron. 1:30).

The unit consists of his mother’s sage advice to prepare him to rule.

1. The king’s mother teaches him (31:1‑2).

2. He is warned against dissipation with women (31:3).

3. He is warned against drunkenness (31:4‑7).

4. He is admonished to protect the weak (31:8‑9).

I. The Paean to the excellent woman (31:10‑31).

This is an acrostic piece that is thus different from the rest of Proverbs and should be considered as a unit.

“This portrait of an industrious, competent, conscientious, pious woman is a conclusion well-suited to a book which teaches the nature and importance of a life lived in obedience to God in every detail.”20 Perhaps it is tied in with “wisdom” as a woman (Cf. chaps. 1—9).

The word excellent in Hebrew is ḥayil חַיִל usually translated “strength,” “wealth,” or even “army.” Here it is speaking of the high qualities of the woman.

1. She provides an excellent counterpart to her husband (31:10‑12).

2. She provides food like a merchant ship (31:13‑14).

3. She rises early to provide for her household (31:15).

4. She barters real estate (31:16).

5. She looks after crops (31:17‑18).

6. She spins and helps the needy (31:19‑20).

7. She provides clothes for her family (31:21‑22).

8. Her character lends dignity to her husband (31:23).

9. She makes enough to trade (31:24‑25).

10. She speaks wisely (31:26‑27).

11. Her husband and her children praise her (31:28‑31).

This woman is a paragon, to which all may aspire, but few attain. In Proverbs, the woman often has more than a literal meaning. So here, this paragon may also represent wisdom.

Thus, ends the book of Proverbs. a veritable mine of wise teaching. May the Lord help us to become more like the Christian ideal through its reading.

1S. LaSor, et al, Old Testament Survey, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982, pp. 533‑34.

2See further, p. 9, “Proverbs tend to be stated in absolutes”

3LaSor, et al., OT Survey, pp. 548‑49. See also B. S. Childs OT as Scripture, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1979, pp. 551f for the monarchy as the cradle of the Proverbs.

4D. Kidner, Proverbs, an Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries, Downers Grove, IL Intervarsity Press, 1964, p. 26. See also Roland Murphy, The Tree of Life, New York: Doubleday, p. 3, says, “The Sages—Who Were They? We can answer this question in a limited way. We know that Qoheleth was a sage, for in Eccl 12:9 he is called a hakam, who ‘taught the people knowledge, and weighed, scrutinized and arranged many proverbs [meshalim].’ But the precise circumstances of his activity are unknown to us.” Crenshaw, p. 31, says, Sirach 38:24—39:11 The wise man must have leisure to study the law. Hence, he probably belongs to the upper class. Furthermore, he will not make “prophetic statements” but rather observes what happens in life. He has no political power to implement his observations, he can only comment on what should be.

5LaSor, et al., OT Survey, pp. 557‑58.

6Roland Murphy, The Tree of Life, New York: Doubleday, 1990, p. 1, says, “The most striking characteristic of this literature is the absence of what one normally considers as typically Israelite and Jewish. There is no mention of the promises to the patriarchs, the Exodus and Moses, the covenant and Sinai, the promise to David (2 Sam 7) and so forth.”

7Crenshaw, Old Testament Wisdom, an Introduction, p. 49.

8See Ibid., p. 32.

9Ibid., p. 32.

10Ibid., p. 57.

11In the Old Testament context, the son was the center of attention. Consequently, the gender references will be in that light. In the modern context, the proverbs should be looked upon without respect to gender, i.e., women should reverse the gender where appropriate.

12Cf. Isa. 32:6 for a summary of a fool, and see Kidner, Proverbs pp. 39ff for an excellent discussion. Chaps. 1‑9 primarily clarify the issues involved in the choice of wisdom or folly, righteousness or wickedness and to prepare for several hundred proverbs that follow. (See LaSor, et al.., OT Survey.)

13Kidner, Proverbs, pp. 41‑42.

14See R. B. Y. Scott, Proverbs in Anchor Bible, NY: Doubleday, 1981, pp. 69‑73, for an excellent discussion of this issue of the hypostasis of wisdom.

15P. W. Skehan, Studies in Israelite Poetry and Wisdom, p. 25, shows that the name Solomon numerically equals 375. He further argues that there are a total of 932 lines in Proverbs. Solomon = 375, David = 14, Israel = 541 for a total of 930.

16Scott, Proverbs, p. 83.

17Scott, Ibid., pp. 130‑131.

18Kidner, Proverbs, p. 24. Cf. “The Instruction of Amen-em-opet” ANET, p. 421.

Related Topics: Introductions, Arguments, Outlines, Teaching the Bible

2. Job

Related MediaSee standard introductions but especially Marvin H. Pope, Job, in the Anchor Bible and LaSor, Hubbard and Bush, Old Testament Survey.

Job and Qoheleth are a response to Wisdom teaching in the ancient middle east. It is good to act wisely, but one should not expect the outcome of one’s acts to turn out as hoped or expected. Job is the ideal person as a man of integrity (תָּם tam). Therefore, his life and example are a response to the common, absolute ideas about wise living.1

I. Date of the book

Since wisdom literature is found in surrounding cultures as early as the second millennium, Pope says that the core of Job could have originated that early. He places the composition in the seventh century. Certainly, the setting of the book is patriarchal.2 The events of the book are surely from the patriarchal period, but the book was probably not put into writing until the heyday of wisdom literature which began with Solomon (1 Kings 4:29‑34) and included Hezekiah (Prov. 25:1).

II. The Text of the Book

The Hebrew of Job is very difficult in places. Not only is it poetry, itself enough of a problem, linguistically it has at least one hundred hapax legomena (words used only one time in the Bible). Attempts to understand these words through cognate languages helps, but not all the problems are solved at this point.

III. The Message of the Book

We have been saying that Samuel/Kings in particular have been based somewhat on the Deuteronomic or Palestinian covenant that taught the Israelites that God blessed those who were obedient to Him and judged those who were disobedient. This concept of retribution theology is certainly correct to a point, but God is not limited to that modus vivendi. He also reserves the right to postpone judgment for sin or blessing for obedience. The failure to comprehend this led to the debate in the book of Job in which both Job and his friends argued from the retributive base alone. Job says God must be unjust for punishing him when he is innocent, and his friends say that God would not be punishing him if he were not guilty. What they both failed to reckon with was God’s sovereign right to allow just people to suffer and unjust people to prosper. The psalmist grapples with this same situation (Ps. 73) as does Jeremiah (12). The disciples of Jesus reflect the same error when they ask their master, “Who did sin, this man, or his parents, that he was born blind?” (John 9:2).

Delitzsch on Job.3

A. The Book of Job shows a man whom God acknowledged as his servant after Job remained true in testing.

1. “The principal thing is not that Job is doubly blessed, but that God acknowledges him as His servant, which He is able to do, after Job in all his afflictions has remained true to God. Therein lies the important truth, that there is a suffering of the righteous which is not a decree of wrath, into which the love of God has been changed, but a dispensation of that love itself.”

B. Not all suffering is presented in Scripture as retributive justice.

2. “That all suffering is a divine retribution, the Mosaic Thora does not teach. Renan calls this doctrine la vieille conception patriarcale. But the patriarchal history, and especially the history of Joseph, gives decided proof against it.”

3. “The history before the time of Israel, and the history of Israel even, exhibit it [suffering that is not retributive] in facts; and the words of the law, as Deut. viii. 16, expressly show that there are sufferings which are the result of God’s love; though the book of Job certainly presents this truth, which otherwise had but a scattered and presageful utterance, in a unique manner, and causes it to come forth before us from a calamitous and terrible conflict, as pure gold from a fierce furnace.”

C. Suffering is for the righteous a means of discipline and purification and for dokimos testing of his righteousness.

4. “(1.) The afflictions of the righteous are a means of discipline and purification . . . (so Elihu) … (2.) The afflictions of the righteous man are means of proving and testing, which, like chastisements, come from the love of God. Their object is not, however, the purging away of sin which may still cling to the righteous man, but, on the contrary, the manifestation and testing of his righteousness.”

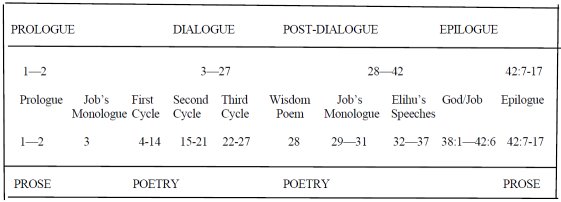

IV. The Structure of the Book

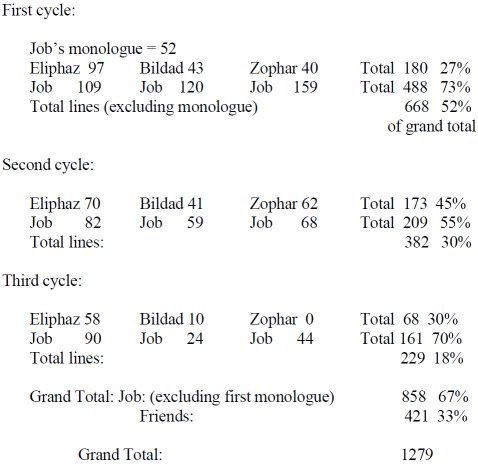

V. Comparisons of lines in the cycles

VI. Outline of Job.

A. The prologue (1:1‑2:13).

1. Job is introduced as a man who worships God (1:1‑5).

Job lived in the land of Uz (an ancient name) and was a righteous man. God’s blessing in his life was evidenced by his physical wealth and large family. He is described as a תָּם tam man. This word means that he was a man of integrity.

There are two areas that have been identified with Uz. The first is around Damascus and linked with the Arameans. The second is Edom and the area of the Edomites.4

2. Job is tested to prove that his faith is not dependent upon his wealth (1:6—2:10).

a. The first test comes in the loss of children and wealth (1:6‑22).

The two great symbols of God’s blessing for faithfulness and righteousness in the OT are wealth (things and children) and health. The book of Job sets out to test the retributive thesis on these two grounds immediately. The first great test comes in the loss of his animal wealth (note the dramatic effect as the story unfolds). Then the word comes that he has lost all his children. Job accepts his fate and refuses to blame God.

The heavenly scene in this chapter is striking indeed. We have a person named the Satan (הַשָּׂטָן haśatan who appears in the heavenly court to accuse Job. The Hebrew word satan as a verb means “to accuse.” Consequently, the noun means “the Accuser.” This scene teaches us a number of things: Satan has access to God in some way; he accuses people to God; God allows Satan certain latitude in dealing with people; and God protects people from Satan. These issues are all peripheral to the story that Job, a good man, suffers unjustly because of Satan’s accusations.5

b. The second test comes in the loss of his health (2:1‑10).

The speech of Job’s wife is interesting. The Hebrew gives her six words, but the Greek adds four verses. The most common attitude about this addition is to assign it to the imagination of the Greek translator or a later editor who, as Davidson says, felt “no doubt, nature and propriety outraged, that a woman should in such circumstances say so little.”6

3. Job’s friends come to “comfort” him (they become the foil in the debate about retributive justice) (2:11‑13).

Eliphaz the Temanite: “Meaning, possibly, ‘God is fine gold.’ According to the genealogies, Eliphaz was the firstborn of Esau and the father of Teman, Gen xxxvi 11,15,42; I Chron 1 36,53”7 Teman is from the Hebrew word yamin or right hand (looking east, the right hand is south). It is associated with Edom (cf. e.g., Jer. 49:7). Bildad the Shuhite: The name Bildad is of uncertain origin. Shuah is the son of Abraham and Keturah. Zophar the Naamathite: the name is found only here, and the location is uncertain. The point of the passage is that these men represent very wise men of the east who are capable of locking horns with Job on this difficult subject of suffering.

B. The Dialogue (3:1—27:23).

1. Job’s monologue (3:1‑26).

a. Job laments that he was ever conceived (3:1‑10).

The whole point of the curse is to say that he should never have been born. It is not so much that he wants to curse his birthday as to say “my life is so bad, it would be better if I had never been born” (cf. Jer. 20:14‑18).

b. Job laments that he did not die at birth (3:11‑19).

If it were necessary for Job to have been born, he should at least have died at birth.8 The Hebrew is nephel tamun (נֵפֶל טָמוּן), lit.: a hidden fall.) Had he died at birth he would have been in Sheol where he would be suffering no pain. (The Hebrew concept of Sheol was vague. It was a place where all went after death [righteous and wicked]). It is rather shadowy and fearful, but better than painful life. Otherwise it is to be avoided. The NT reveals the One who came to “deliver them who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to bondage” (Heb. 2:15).

c. Job laments that he cannot die (3:20‑26).

Job says, finally, that if he had to be conceived and born, at least he should be allowed to die in the midst of suffering.

2. The dialogue with the three “friends” (First Cycle) (4:1—14:22).

a. Eliphaz’ response to Job’s monologue (4:1—5:27).

He chides Job for being impatient and complaining but acknowledges his piety (4:1‑6).

Eliphaz begins the argument that will be repeated in a dozen different ways throughout the book. Blessing comes on the obedient and suffering on the disobedient, ergo: Job has sinned. Eliphaz begins gently with Job, but when Job stubbornly defends his position, the men get more severe in their statements.

He argues that sin brings judgment (4:7‑11).

All human experience, he says, proves that the innocent do not suffer (if they suffered they were not innocent). This flies in the face of actual experience unless one interpret circumstances to fit the theory (which they apparently did).

He argues (quoting his vision) that man cannot be just before God. This seems to be a statement of frustration: man cannot avoid trouble (4:12‑21).

There is no use calling on even angels to help because man is destined to trouble (5:1‑7).

He argues that there is still hope in God who sets all things right (5:8‑16).

God is the great creator. He is beyond human comprehension, but He still has compassion on the human being. He will judge the wicked and vindicate the just. Therefore, he pleads for Job to repent.

He argues that reproof and correction are part of God’s works, and that man should submit to their inevitability and reap their benefit (5:17‑27).

The implications of this argument are clear enough: Job has sinned and is therefore suffering. If he will accept God’s punishment and repent, he will be restored to a place of blessing.

b. Job responds to Eliphaz’ arguments (6:1—7:21).

Job complains about his painful state (6:1‑7).

He says that his pain ought to be measured and examined so that people would understand what he is going through. God’s unfair punishment has been harsh, and he suffers from it. He would not be complaining if he did not have good reason.

Job cries out for God to finish him off (6:8‑13).

Since God has brought this great pain to Job, he insists that God should finish what He has begun and kill him. For his part, he has not denied the words of the Holy One, therefore, the least God can do is put him out of his misery.

Job complains about the lack of support from his friends (6:14‑23).

He likens them to a wadi (that only occasionally has water). The caravans hurry their steps toward it thinking they will get water only to find it dry. So are Job’s friends. He has never asked them for money or help; now he only asks them for understanding, but they will not give it.

He demands they tell him what they think he has done (6:24‑30).

Job speaks harshly of his friends’ injustice. He says they would cast lots for orphans and barter over a friend. In other words they are completely unjust in dealing with him. He demands that they stop treating him as they have.

He complains again of his state (7:1‑10).

It is not only his own situation of which he speaks: mankind in general suffers like one impressed into harsh labor, like a slave panting for the shade. So is Job: he suffers physically, his days are short, and he expects to go to Sheol.

He complains of God’s constant demands upon him for right living (7:11‑21).

Job says that God has put a constant watch over him like the sea or the sea monster. This watch is not for his good, but to catch him in evil so as to judge him. Job says that God is unrelenting in his demands, and there is no way to escape Him. God will not pardon him, and he expects to die.

c. Bildad gives his first speech (8:1‑22).

He challenges Job to confess and be restored (8:1‑7).

Bildad angrily tells Job that God is not unjust, and therefore whatever has happened is just. However, in the retributive justice argument, this means that Job’s sons must have sinned to deserve death. Job need only seek the forgiveness of the Almighty to be restored to the place of blessing.

He tells Job that the wisdom of the ages teaches that those who forget God are judged. Therefore, Job needs to confess (8:8‑22).

d. Job responds to Bildad’s arguments (9:1—10:22).

He says that God is sovereign and inscrutable (9:1‑12).

Part of Job’s defense is that God cannot be approached by one who wants to present his case. In this unit, he sets forth the idea that no one can enter a court case with God, because God is completely dominant and man is fragile and weak before Him.

He says that God is unfair in his treatment of Job (9:13‑24).

Job’s words reach the point of blasphemy (as his friends later point out). Job is defenseless before Him, He abuses Job with suffering, and even though Job is absolutely innocent, God declares him guilty.

He says that he is not equal to God and therefore cannot defend himself (9:25‑35).

No matter what he might do to cleanse himself, God would push him into the mud and declare him polluted. There is no lawyer to stand between God and Job to give him a fair hearing. If God would remove His punishing rod, Job would not be afraid to confront Him, but God is completely unfair in the way He deals with His creatures.

He says that God does not understand the human state (10:1‑7).

Since God is not human, He cannot possibly understand human suffering. He claims that God knows that he is innocent and yet refuses to deliver him from suffering.

He says God created him but has cast him off (10:8‑17).

Job speaks bitterly of the finite being God has created only to abandon to suffering. Not only so, but God judges him even if he is righteous. Job dare not lift his head lest God hunt him like a lion.

He returns to his lament about death in chapter 3 (10:18‑22).

Job pleads with God to withdraw from him and let him die in peace. If God allowed him to live at the beginning, surely he can give him some peace now.

e. Zophar gives his first speech (11:1‑20).

He charges Job with arrogance in saying he is innocent (11:1‑6).

The rhetoric begins to heat up as Zophar charges Job with scoffing by saying “My teaching is pure, And I am innocent in your eyes.” He wishes God could speak! If He could, He would say that Job had not suffered enough, since God has not held all his iniquity against him.

He argues that God is transcendent (11:7‑12).

Job’s finiteness means that he cannot take on God in this discussion of righteousness. God knows false men, and obviously He knows Job. Man is a fool to try to argue with God.

He argues that Job should confess and then enjoy the forgiveness and blessing of God (11:13‑20).

In a beautiful poem, Zophar tells Job of the great blessing that would ensue on the repentance of this sinner. He must put iniquity far away, but if he does he will find unprecedented blessing.

f. Job responds to Zophar’s arguments (12:1—14:22).

Job chides his friends and says that God is responsible for all things (12:1‑6).

He argues that he is as intelligent as they are. In his past he trusted God and was known as a man of prayer to whom God listened. But now he sees that those who reject God are at ease and those who serve Him are in trouble.

He says that even nature teaches that God is responsible for all things (12:7—13:2).

He then proceeds to list all the things, good and bad, for which God is responsible. God seems to take delight in turning things on their head (“He makes fools out of judges”). Life, says, Job is unfair; he has seen it all and knows that what he says is true.

He demands an audience with God and declares that his friends would be routed if they met God (13:3‑12).

God, says Job, does not need a defender, least of all those who would be dishonest in their dealings with Him. They must stand before God someday, and God will pronounce them guilty for their false charges against Job. Their arguments are completely worthless.

He declares his innocence (13:13‑19).

In spite of all the harsh things Job has said about God, he says that He will trust Him even if He slays him. He believes he would be cleared if he could only argue his case before God.

He challenges God to be fair to him (13:20‑28).

He asks God for two things (stated in reverse form) (1) to remove His hand from him and (2) not to terrify him with fear. If God will do that then Job will be able to speak to Him and defend himself. He demands that God tell him what his sin is and why He is causing Job to suffer so.

He argues that since man is born as a finite creature, God should let him alone (14:1‑6).

Mortal man stands no chance before God. He is weak and limited, yet God judges him. If man is indeed innately sinful and mortal, how can God expect an unclean person to be clean. He therefore pleads with God to avert His face from this weak creature.

He argues that man’s life is hopeless (14:7‑12).

He extends the mortality theme by contrasting man to a tree. The tree can flourish even after it has been cut down, but man dies and that is the end. Job believes in life after death, but that life is not in the normal sense. There will be no return to life on earth as now known.

He prays for God to have mercy on him (14:13‑17).

Since Job is suffering unfairly from the wrath of God, he pleads for God to hide him (as far away as Sheol) to give God’s anger an opportunity to subside. If he dies, he will not live again (in the normal sense on the earth), therefore, he prays for God to let him live until God’s anger is turned back. So that God will remember him after His wrath has subsided, he wants God to set a limit or mark to remind Him that He has hidden Job. The word “change” in 14:14 (ḥaliphathi חֲלִיפָתִי) is the same as the word “sprout” in 14:7 (yaḥaliph יַחֲלִיף). Job is asking God to let him return to earth again in a renewed body.9

He complains that God is almighty and unmerciful (14:18‑22).

Job’s defense has moved from declaring his innocence (which he continues to do) to arguing from the mortality of the human race. Since God created man, He should not hold man’s limitations against him. He should give him a break by recognizing his weakness and not judging him.

3. The dialogue with the three “friends” (Second Cycle) (15:1—21:34).

a. Eliphaz responds the second time to Job’s speech (15:1‑35).

He rebukes Job for his lack of respect for God (15:1‑6).

Job’s blasphemous words have been created by the guilt within him. His own bitterness and rebellion are evidence that he is not innocent. His evil defense makes it even more difficult to get at the matter spiritually.

He rebukes Job for arrogance in assuming he knows more than others, even more than God (15:7‑16).

Eliphaz demands that Job recognize the wisdom of others and to accept their conclusions. Man is indeed mortal as Job has said: why then should he think he could argue with God. God does not even trust his holy angels, why should he declare sinful man innocent?

He details the suffering of the wicked man who rebels against God (15:17‑35).

Eliphaz lays out in great detail the problems that come to a man who arrogates himself against God. He seems to be including Job in that category.

b. Job responds the second time to Eliphaz’ speech (16:1—17:16).

He complains about the lack of sympathy in his three friends (16:1‑5).

A speech dripping with sarcasm is delivered against the three friends. They are “sorry comforters.” They sit in self-righteous comfort and condemn a man who suffers. Their statements are therefore worthless.

He details the suffering he has undergone at the hands of evil-doers and even at God’s own hand (16:6‑17).

As Eliphaz sets out the sufferings of the unrighteous man, Job lays out the unjust sufferings he has endured All this has happened even though there is “no violence in my hands, and my prayer is pure.”

He cries out for vindication before God (16:18—17:2).

Job has been wronged as was Abel. Abel’s blood cried for vengeance, so does Job’s. Only it is God who has committed the crime. Who then can defend Job? He asked for an umpire in 9:33 (mokiaḥ מוֹכִיחַ), a vindicator (redeemer) in 19:25 (goel גֹּאֵל); an interpreter in the passage before us; and an intercessor in an extended passage in 33:23ff. Job is begging for someone to stand between him and a holy righteous God. While Job is accusing God of injustice, he has also pled the cause of mortal man. This thinking, preliminary as it is, underlies the idea of the mediator who was Christ Jesus (1 Tim. 2:5).

He asks for someone to defend him (17:3‑5).

Job wants God to exchange pledges with him so that there will be integrity in their argumentation. He challenges the integrity of the friends by saying that they lack understanding and are really informing against a friend for a share of the spoil. This is a strong charge.

He says he suffers as a righteous man and therefore other right-eous people will be appalled (17:6‑16).

Job argues that people who are righteous and discerning will understand that he is suffering wrongfully. The clear implication is that his friends are not righteous. In spite of his suffering, he will maintain his integrity and ultimately expects to be vindicated (as he indeed was).

c. Bildad responds the second time to Job’s speech (18:1‑21).

He rebukes Job for his outburst against his friends (18:1‑4).

He asks Job why he thinks he should receive special treatment. Will the earth be abandoned for Job’s sake or the rock moved from its place? Who does Job think he is?

He sets forth in elaborate and gruesome detail the fate of the wicked (18:5‑21).

d. Job responds the second time to Bildad’s speech (19:1‑29).

He rebukes his friends again and specifically states that God is the cause of his problems (19:1‑6).

He complains that God will not give him justice (19:7‑12).

No matter where he turns, God is against him. When he cries out for help, God does not answer him. God has treated him as an enemy and has brought his army against Job.

He complains that everyone has turned against him (19:13‑22).

All his family, his wife, his friends and acquaintances have turned away from him. Even his three friends are mistreating him in the same way God is doing.

He cries out for a recording of his justice and gives a strong testimony of faith in God (19:23‑29).

19:25, 26 says: “And as for me, I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last He will take His stand on the earth.” “Even after my skin is destroyed, yet from my flesh I shall see God.”10